It’s a wonder that any of us find good, new puzzle games and start playing knowing nothing about them. I’ve been persuaded by a propulsive atmosphere, an intriguing premise, and snappy controls when deciding what to play, all the while remaining completely unaware of what the game is actually about. Fans have good reason to be cagey around the details of an experience largely driven by the excitement of the unknown.

We live in a time where innocently surfing the web can result in seeing a single screenshot and completely ruining a game, so with that in mind, how much can be said about a game without spoiling the fun? Where do you turn when you need hints but not solutions? How, exactly, should we talk about puzzle games?

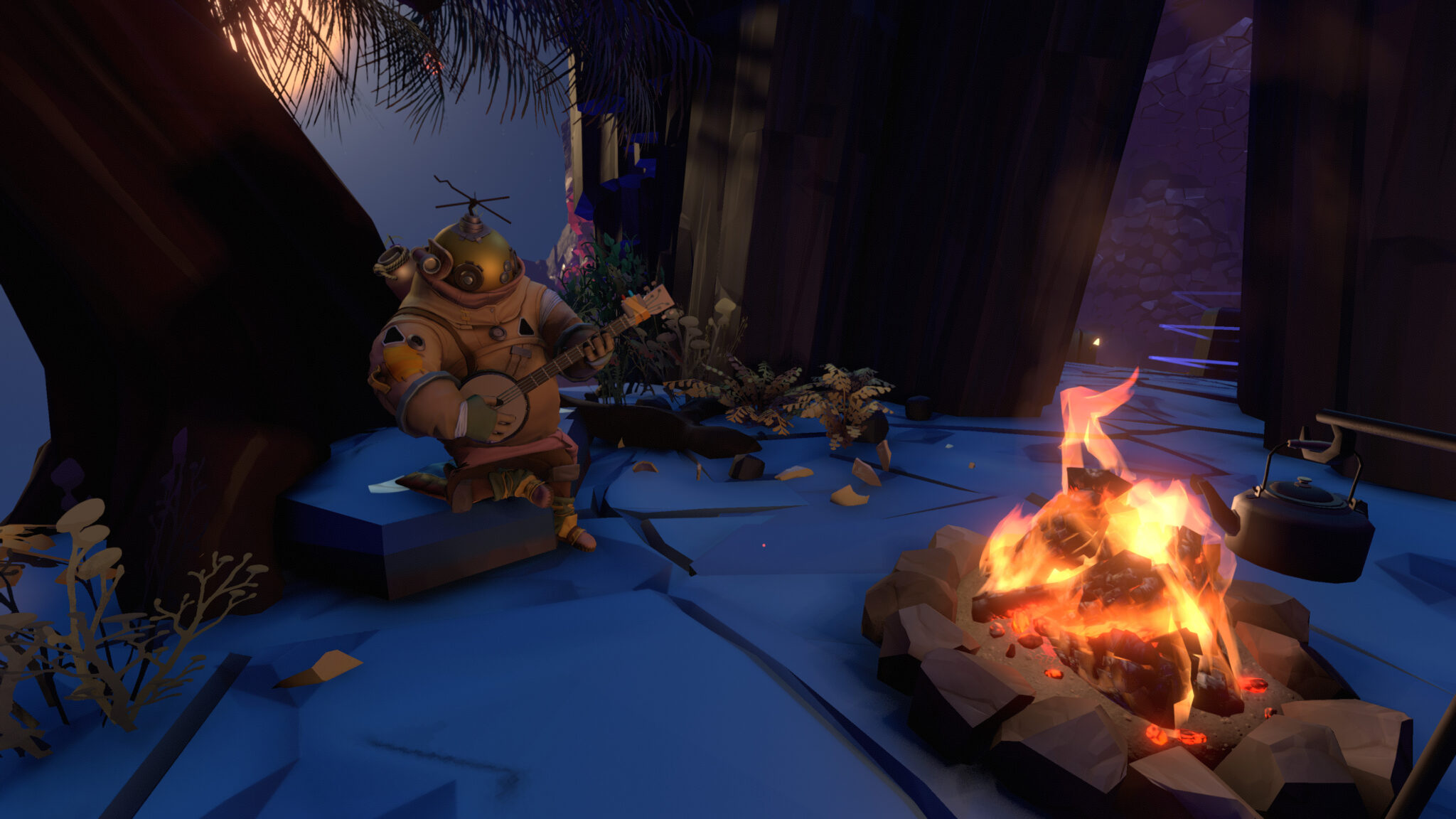

Outer Wilds represents my biggest blind spot in the canon of great mystery games. I’ve had to remain very careful in conversations with other enthusiasts of the genre, who are on the whole happy to accommodate my ignorance. Ignorance, after all, is the primary currency of the so-called information game, defined by Tactical Breach Wizards developer Tom Francis as a game in which you progress by uncovering and deploying information. It’s literally impossible to participate in an information game if you already know the information. They aren’t fighting games, where thousands of similarly shaped matches are given texture by moment-to-moment chaos; they are machines finely tuned to produce specific insights in a satisfying sequence. Roller coasters, not merry-go-rounds.

When I picked up Outer Wilds, I knew I’d have the best experience if I went in blind. But that’s exactly the problem, right? It’s vanishingly rare, if not impossible, to go into a game blind. Outer Wilds’ Steam page advertises that its mystery centers on a “solar system trapped in an endless time loop,” already revealing the game’s first surprise. I’m told of something at the heart of Dark Bramble, alien ruins on the Moon, and an underground city about to be buried by sand, all before I’ve even made the decision to purchase the game. It’s also critically acclaimed, so even if I bounce off at first—as happened during my first loop, where I found the three-dimensional movement incredibly disorienting—I know I’ll likely be rewarded for pushing through that initial barrier. All of these details are little compromises on the game’s information, but necessary to buy me in on the experience.

There are other reasons to seek out additional information even after buying in. Because information equals progress in this genre, there’s typically no way to brute force the path forward whenever you find yourself truly stuck. You either know, or you don’t. I’ve met plenty of thinky players who reject any help not contained within the game itself—I’ve been that person—but these days, with so much to play, I simply don’t have the heart to ironman a puzzle for hours and hours just to maintain a sense of pride. I’d rather see more of what a game has to offer. Sue me.

This is where I run into the biggest trouble. It would be awfully convenient if mere googling could produce some one-size-fits-all hint guide to whatever specific challenge I’m facing at that moment. Guide writers do a great job, but the step-by-step walkthrough approach is necessarily blunt. Often a gentle nudge is all I need to unsnag myself from a tricky puzzle. To make matters worse, Googling anything these days is liable to bring up an AI overview that manages to disclose key elements while simultaneously being completely wrong. In short, no automated solution exists. No automated solution can exist.

Of course, some games are so intricately constructed that searching for anything damages the integrity of the entire construction. Blue Prince is one of these, and it’s a game that had two lives for me. The first was when I got to play pre-release. I sat in the dim of my office, spidering out alone into the nooks and crannies of Mount Holly. I was impressed, but felt like I was missing something important. The second life of Blue Prince began when I realized what that was: when my friends were finally able to access the game, uncover mysteries of their own, and discuss how they all fit together.

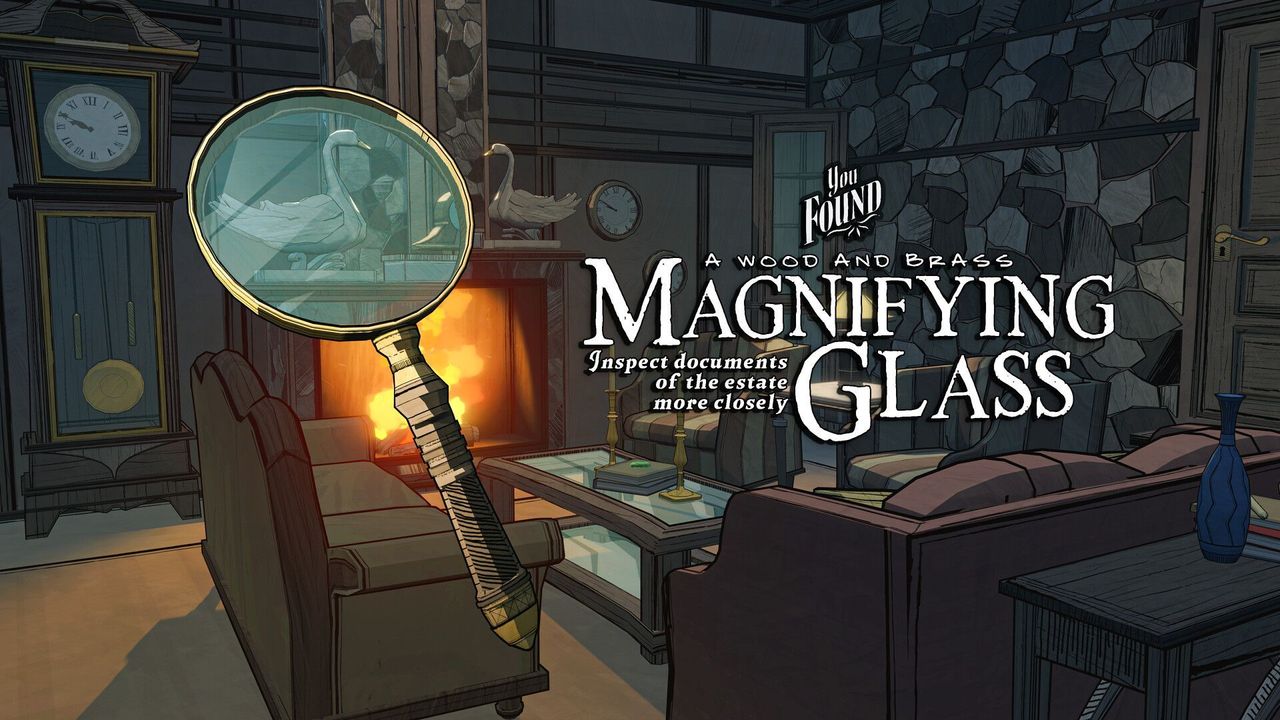

It was this interpersonal quality that made the game click for me, as well as getting me unstuck from certain ruts that I’d fallen into over the course of play. So often with a game like Blue Prince, I jump to an incorrect conclusion at the start that makes it difficult to see a puzzle clearly later on. Others will jump to different conclusions or have different ideas. Just talking it through was enough to unstick my thinking. When my friends had already solved the puzzle I was stumped on, they were able to delicately circle the answer to let me draw conclusions mostly on my own, and I was able to do the same for them. We’ve all had those conversations: “OK, so have you been to the Dark Room? Did you look at all the photos? Did you use the magnifying glass?”

They’re very similar to the Universal Hint System-inspired guides of The Crimson Diamond and Strange Jigsaws, to my mind the gold standard of online walkthroughs. In those guides, leading questions guide the player’s attention, with only the final clue giving away the answer in its entirety. This method succeeds because it requires the writer—in TCD and Strange Jigsaws, the developer—to put themselves in the player’s shoes and imagine what questions they might be forgetting to ask themselves. In a word, they show empathy for the player.

Forums are also handy for this kind of leading approach, especially around huge games like The Outer Wilds and Blue Prince. Reddit in particular is almost pathologically spoiler-avoidant, to the extent that even posters who ask direct questions won’t receive direct answers. But this is also a kind of empathy. Players tend to care about the experience of players in the same community, as evidenced by the thousands upon thousands of how-to videos, lore explainers, and meta discussions happening for absolutely free all across the internet. For information games, that means trying to lead others to the answer without ruining the thrill of discovery. Many will have already experienced that thrill, and therefore seek to replicate it for others.

Avoiding spoilers, seeking help, posting guides—these are all extensions of empathy. To discuss information games at all is to put ourselves in the mind of another player, to inhabit their perspective. And the risk of ruining someone else’s experience isn’t all that high, either. Some amount of spoiling is unavoidable, but when we engage with other players and learn from their experience, it doesn’t feel like cheating. Co-solving can be just as fun as going solo, if not more fun. I’ve solved plenty of puzzles that made me feel like a genius on my own. None of those compare to the times when I’ve fully mind-melded with another player, and the final piece clicks into place for both of us. Our eyes light up, we turn, we inhale—and that’s the best way I know of to talk about puzzle games.