Reuters, Bloomberg, and AlphaSense built information markets worth billions. Each rode a wave of technological transformation—but technology alone doesn’t explain their rise. The real engine is older, simpler, and more durable: shaping markets well before any technology existed. Understanding its true nature reveals why each cycle creates new winners and why AI presents an opportunity to build anew.

The first harvest of the season had arrived. Willem, a 7th-century farmer, sold his crop of barley at the local market for four dinari per bushel. Honest work, fair pay, predictable life.

His neighbour, Henrik, farmed the same land and grew the same barley, yet lately he’d been absent from the local market. Willem’s wife—Mara—sharp-eyed and curious, decided to follow Henrik one morning. She discovered he’d been selling in a town a few miles west, for six dinari per bushel.

Mara didn’t tell her husband just yet. She had a better idea. Most of her friends, the other wives in the neighbourhood, already travelled between towns early each morning to sell milk. She recruited them to report back the going rate for barley in each town. For one dinari a day, any farmer could now purchase from Mara barley prices across towns and decide where to sell for maximum profit.

The arbitrage opportunity didn’t last long. As more farmers learned about the price differences, they began routing their supply to the highest bidder. Prices converged across towns as the invisible hand adjusted to the new information flow. Within weeks, barley sold for five dinari everywhere.

However, Mara didn’t stop charging once prices equalised. She was no longer selling arbitrage opportunities. She was selling certainty. A farmer who paid one dinari knew he wasn’t leaving money on the table. Any farmer who didn’t, risked being outcompeted by those who did. Information asymmetry in competitive markets is ruinous.

Entrepreneurial as she was, Mara had another insight. Why stop at barley prices, and why stop at farmers? The local wholesaler needed to know wheat prices across towns. The visiting merchant wanted to know which town had cheap wool. She built a network, hiring runners to collect price information for dozens of goods across a dozen towns. Though she would never use the term, she uncovered a subscription-based data-aggregation model that would prove durable for centuries.

In 1980, two economists, Sanford Grossman and Joseph Stiglitz, published a paper that challenged the Efficient Market Hypothesis (EMH), an idea that had dominated financial theory for two decades.

The EMH held that market prices reflect all available information. If IBM traded at $100, that price encoded everything knowable about the company—its earnings, prospects, management quality, competitive threats. Thousands of informed traders had collectively processed all relevant data and bid the stock to its true value.

Grossman and Stiglitz identified a fatal contradiction. If prices already reflect all information, why would anyone spend resources gathering it? Information is costly—you have to collect data, analyse it, and still make decisions under uncertainty. But if the price already tells you everything you need to know, gathering information is irrational.

Yet if nobody gathers information because prices already reflect it, then prices can not reflect information. The only mechanism for information to enter prices—through traders acting on it—breaks. Paradoxically, perfectly efficient markets destroy the incentive for the very activity that makes them efficient. Information can’t be both free (reflected in prices) and costly (requiring effort to gather) at the same time. One or the other has to give.

Grossman and Stiglitz proposed an alternative: markets can never be perfectly efficient. There must always be enough information asymmetry—enough gap between what prices reveal and what informed traders know—to compensate those traders for their costly research. Markets, they realised, exist in a perpetual state of almost-efficient, never quite arriving.

An equilibrium of disequilibrium.

Disequilibrium is the lifeblood of information markets. Had the two economists ventured beyond informed traders and their transitory profits, they would have noticed that enduring profits accrued instead to those who controlled the information flow.

Thirteen centuries earlier and unencumbered by economists, Mara had found the most profitable position inside the paradox. Markets were subject to entropy. Although prices initially converged, they could diverge again at any time—drought in one region, a festival driving demand in another, disease hitting a farmer’s crop. Mara’s value endured because the cost of not knowing in a dynamic market exceeded her subscription fee.

Value that was about to climb of its own accord. As the friction of vast distances collapsed, the market discovered a new asymmetry in its place. Farmers who lived closest to her morning briefing point realised they could reach the information first. An hour’s head start meant arriving at the highest-bidding market before it grew crowded, securing the best stall positions, and capturing the first wave of buyers. All while distant farmers were still making their way to Mara.

Mara naturally priced the early birds higher. The other farmers, though, weren’t about to let their profits disappear that easily. They soon paid her for an express messenger on horseback to bring the information directly to them. The cost of the same information had suddenly increased across all market participants. Independent of any change in the economic value of barley itself, the market had increased the economic value of her information1.

The network’s structural edge ran deeper. While Henrik’s information edge collapsed as prices adjusted, perhaps permanently, Mara’s business edge persisted. She wasn’t exploiting a single information asymmetry temporarily. She was collecting fees for reducing asymmetry for every market participant, perpetually. Her model increased the addressable market, generated positive-sum value, proved durable across market conditions, and risked no capital.

Most importantly, it accrued value through natural competition and entropy. Mara didn’t have to hunt for the next asymmetry to monetise. Competition among farmers, each seeking an edge over the others, surfaced it for her. Entropy—the market’s inherent tendency toward disorder2—guaranteed it would keep appearing. As distance collapsed, latency emerged. She simply had to maintain her position as the infrastructure that compressed whatever friction came next. And the cycle repeats.

In fact, the cycle has repeated six times. Interestingly, unlike in Mara’s case, each cycle created a new information powerhouse, as the prior cycle’s dominant player failed to extend its advantage. We now find ourselves at the advent of the seventh cycle, and the pattern is poised to repeat.

To understand why, this post traces the evolution of information markets from before the telegraph up to the transformer. It reveals how asymmetries shifted in each cycle, where opportunities surfaced and why new entrants won. The pattern that emerges presents the latest cycle as a unique and underappreciated opportunity to those bold enough to compress it.

I hope you enjoy this brief history of information markets.

Chapter 1

It’s closing time at the Antwerp Stock Exchange, summer of 1531. The crowd that had been shouting bids and offers for six hours begins to thin. Pieter, a merchant from Delft, has just sold his last sack of pepper at 25 ducats. A reasonable price, he’s pleased.

But walking home that evening through narrow streets, doubt crept in. That afternoon he’d heard whispers—ships delayed in the East Indies. Had that news reached other traders? Had prices moved after he sold? By tomorrow morning, the price could be anything. And whatever it closed at existed only in the memories and broker journals of those who were there to hear it called out.

In 1531, at the world’s first purpose-built commodity exchange, prices were spoken, agreed upon, traded, and forgotten. Without physical presence, there was no access to price information. This created a peculiar market participant: the ever-present trader. Merchants couldn’t be informed by showing up occasionally. They had to be there every day, all day, ears tuned to the shouting, eyes watching the crowd’s mood. Miss a day, and you’d lost the thread. Miss a week, and you operated blind. The merchants who understood the asymmetry of presence stationed themselves or their agents at the exchange permanently.

Even presence wasn’t always enough. Memory is fallible. Two traders would swear they’d agreed on different prices for the same transaction that morning. With no independent verifiable record, the past became a blur of half-remembered figures and the future, pure speculation unanchored by any historical pattern.

To address this chaos, the Antwerp exchange appointed officials to record what they heard. These scribes sat at the edge of the trading floor, writing down the prices being shouted, the volumes being traded, and the times of transactions. At day’s end, they’d post these figures on boards in public squares. Others collected that information and distributed currents—early financial newspapers—across merchant communities. What started in Antwerp soon spread to Amsterdam. These scribes weren’t creating new information. Prices still formed through the same open outcry process. They were simply capturing it, making it persistent, and providing verification.

A merchant could now leave the exchange at midday and return to check the closing price. A trader in dispute could point to the posted record and settle the argument. An investor considering a purchase could see what price had prevailed yesterday, last week, or even last month. Information that had been locked inside the exchange walls, accessible only to members and their agents, was now public. The asymmetry had shifted. Merchants no longer had to be physically present during trading hours to be informed. Information outlived the moment of its creation.

By organising ephemeral data into written records, scribes laid the groundwork for the early information vendors. But crucially, they birthed the first public market dataset —price and time, sequentially catalogued. This organised record transformed how markets functioned. Yesterday’s close offered a reference for today’s open. Last week’s prices revealed trends that a single price couldn’t. The dataset laid the foundation for pattern recognition, understanding seasonality, and detecting anomalies. Information could now be studied, compared, and analysed.

However, while scribes created data persistence, that data remained trapped at its origin. A London merchant trading through Amsterdam waited days for letters to arrive by ship or messenger. By the time they learned the price, it had already changed multiple times. Worse, they couldn’t verify the information. Was the quoted price accurate, or had their correspondent shaded it to benefit their position? Without checking the posted bills, they had to trust. And trust, in 17th-century markets, was expensive. Trade routes were beginning to stretch across continents—Dutch merchants operated in the East Indies, British merchants in the Americas. Goods flowed globally, yet price information remained trapped where exchanges were located.

The new asymmetry favoured those with direct access to exchanges with current, verifiable information. Those far away were plagued with delayed, often unreliable data. Closing that gap was where the first great information fortune would be made.

Chapter 2

1840, London. Union Bank faced a tough decision. They needed to know the price of cotton in New Orleans—not last month’s price, not an estimate, but what it was trading at right now. They were about to extend their largest credit note yet. A longtime client needed funds, claiming that the price of raw cotton in New Orleans had moved in his favour and that business was certain to expand.

The bank had three options. Send a clerk on a ship—four weeks one way in good conditions, six in bad weather. In winter storms, ships disappeared entirely, taking whatever information they carried with them. Or intercept the next ship arriving from New Orleans and hope the captain had recent price information. Or make an educated guess based on fragments of information that had trickled into London over the last week through letters and shipping manifests.

Most bankers guessed. The world was economically connected across oceans, yet remained informationally disconnected. It would take one man’s grief and another’s near ruin to solve this.

When his wife died while he was travelling in 1825, the letter took days to reach Samuel Morse. By the time he got home, she’d already been buried. That grief became obsession: there had to be a way to send messages instantaneously across any distance. The physics were understood—Franklin, Volta, Ampere, and Faraday had demonstrated that electricity could travel through a wire exceptionally fast. The problem was encoding.

His solution was elegant: a combination of long and short electrical pulses representing letters. In 1844, twelve years after he first encountered the telegraph, Morse sent his first message from Washington to Baltimore. Forty miles in an instant. The revolution, though, began slowly. Telegraph infrastructure required significant resources—miles of copper wire, poles, relay stations, and trained operators. Early lines only connected nearby cities. But few understood what this meant for markets.

Israel Josaphat was one of them. In 1850, he ran a carrier-pigeon service in Germany, bridging a telegraph gap between Berlin and Paris. Profitable but temporary. He knew it was only a matter of time before the telegraph voided his business. So he pre-empted and pivoted. Uprooting himself to London, he started a financial information service built entirely on the telegraph that had just crossed the English Channel.

In 1851, it was a risky bet. The telegraph was still novel, underdeveloped, and expensive. Prospective clients operated fine for centuries without instant information from foreign markets, so they were unwilling to commit. However, Josaphat understood something they didn’t: in a world where everyone had slow information, slow information was acceptable. But as soon as one participant had fast information, everyone else would be at a crippling disadvantage. He only needed a few early subscribers to prove the value. The rest would come knocking3.

By 1858, Josaphat had expanded across Europe, delivering financial news and market prices from London to Paris, Berlin, and back. Banks that had scoffed a few years ago were now critically dependent. Not having access became commercially untenable.

Then came the transatlantic cable that would seal Josaphat in the annals of history.

In 1866, after several failed attempts and multiple bankruptcies, the first telegraph line was successfully laid across the Atlantic. Messages that had taken six weeks by ship could now be transmitted in two minutes4 - a four orders of magnitude improvement. Markets that had operated in isolation for centuries could now coordinate in real-time.

The capex was punishing. Laying cable across the ocean required capital on a nation-state scale. Operating it required constant maintenance, relay stations, teams of technicians, and fleets of service ships. Yet once a cable was laid, the marginal cost of transmitting one more message was minimal. Josaphat had already built the operational infrastructure in Europe—the telegraph offices, collection networks, distribution agreements, and credibility. Extending his network across the Atlantic would be incredibly costly, but the economics and adoption incentives for his clients remained the same. All he needed was capital, audacious ambition, and disciplined execution. In founder mode, Josaphat lacked none of these5.

Other information vendors leased capacity on existing cables, accepting the constraints and economics dictated by infrastructure owners. Josaphat refused. He found partners to finance his own dedicated line, maintaining his vertically integrated ethos – own the information networks and the physical infrastructure transmitting it. Beyond speed, he realised the value of control, priority access during crises, and the ability to set his own service standards6. When markets panicked and cable capacity became scarce, Josaphat’s clients got through while competitors’ messages queued. That reliability became a competitive moat.

By 1870, he was the primary conduit of financial information between London and New York. The humble pigeon carrier operator now operated trans-Atlantic and trans-continental telegraph infrastructure, global news bureaus, and the leading financial information service. He would go on to become one of the most powerful men of the era, and his name would dominate financial information markets not just for decades but for centuries to come.

We know him by his adopted name, Paul Julius Reuter.

Reuters changed the fabric of information markets. Information no longer existed in isolation, no longer constrained by physical proximity. Price and news from multiple geographies could be collected, compared, and distributed while still relevant. Clients could make decisions based on actual market conditions across their entire operational geography7. Union Bank of London could build its credit book confident of cotton prices in New Orleans.

For merchants and investors alike, the risk profile of international trade shifted. Previously, they’d ship to a foreign port and hope the price would be favourable when goods arrived two months later. Now they could wire ahead, confirm prices, and arrange sales before their ship even left port. The velocity of international commerce would never look back.

Yet the telegraph had limits. It was point-to-point—you had to drop your message at the telegraph office, get it encoded, pay for transmission, and wait for a reply. Then someone at the other end had to decode and hand-deliver that reply to your recipient. While the wires were fast, the human interfaces at each end were slow. It was also discrete and manual. You sent one message, you got one reply. Skilled operators could manage perhaps 25-30 words per minute. Impressive compared to ships, but painfully slow when transmitting a full day’s worth of price quotes for hundreds of securities.

Information thus had to be prioritised. Major price moves, important news, and urgent queries could travel instantly. Routine information, however, still moved slowly, still relied on price summaries in daily newspapers and weekly journals.

The telegraph’s limitations created new asymmetries. Those with dedicated lines and priority access—typically the largest banks and trading houses—could act on information before it reached smaller participants who relied on shared telegraph offices. Geographic proximity to telegraph stations mattered. Cities with direct cable connections had advantages over those that relied on relays. The cost per word meant only the wealthiest could afford frequent information updates.

The telegraph solved transmission infrastructure for the few, but it would need real-time distribution capabilities to bring the masses online. The next innovation would need to flip the telegraph’s design constraints, turning it from a request-response system into a continuous, automatic broadcast stream.

Chapter 3

The New York Stock Exchange, 2:47 PM, October 29, 1929.

The trading floor is pandemonium. Brokers scream, shove, desperate to sell anything at any price. AT&T, down 28 points. US Steel, down 12. Goldman Sachs, down 24.5. Everything is collapsing. Most investors just don’t know it yet.

The stock ticker—that miraculous machine printing prices on continuous paper ribbon—can’t keep up. It’s running 2.5 hours behind. While the market is in free fall that afternoon, the ticker in brokerage offices across the country is still printing prices from the late morning, when things merely looked bad rather than catastrophic.

Some investors watching the tape think they’re seeing current prices. They are buying what appear to be bargains on stocks that can’t fall any further. Others are in panic. Investors who have realised their tape is behind assume the worst and sell, accelerating the crash. By the time the ticker finally catches up—four hours after close—the damage is done. Black Tuesday.

If the last two words were anxiety inducing, take a few moments to email this post to someone in your network.

The ticker had been invented to solve a problem. By 1929, it had become one. Continuous information, it turned out, was only valuable when it was actually continuous. When the flow backed up, it became misinformation.

Six decades earlier, the need was quite different. The New York Stock Exchange was growing rapidly. Hundreds of stocks traded daily. Prices changed constantly. Brokers needed current prices to serve their clients. The only way to get them was to station someone at the exchange to watch trading and telegraph prices back.

That worked when brokers tracked ten stocks and prices changed a few times per day. By the 1860s, active brokers tracked a few dozen stocks, with prices changing every few minutes. During busy periods, the telegraph office couldn’t handle the volume, and messages queued up. By the time a messenger ran from the telegraph office to deliver a price quote, it was stale. The problem was architectural. Brokers needed something fundamentally different: one sender (the exchange), many receivers (every brokerage), continuous transmission, automatic decoding. The technology to solve this existed; someone just had to assemble it correctly.

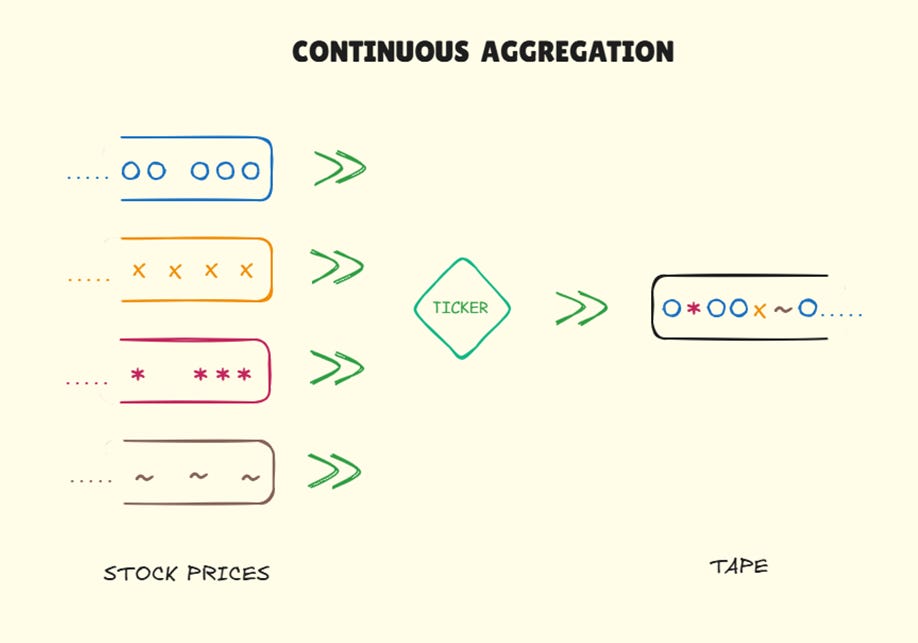

Edward Calahan, a telegraph operator who’d spent enough time around Wall Street, made the first attempt in 1867. He combined three existing technologies: the telegraph for transmission, a teleprinter that automatically decoded electrical signals into printed letters, and a thin paper roll rather than separate sheets, so the printer could run without interruption.

Calahan’s ticker received electrical signals from the exchange and automatically printed stock symbols and prices onto continuously rolling paper ribbon. No human operator to decode Morse code. No messenger to run anywhere. The machine did it all, continuously, as long as the exchange was open.

The ticker created the first real-time information product. Brokers could now stream price updates without leaving their desks. It also introduced subscription economics—monthly fees covering hardware, telegraph connections, technical support, and the data feed. Hardware-as-a-service bundled with information-as-a-service. By 1870, a few hundred tickers had been installed in New York offices by the Gold and Stock Telegraph Company, which commercialised Calahan’s invention.

Yet an unresolved issue threatened the entire system. When a receiver drifted out of sync—missing a signal due to electrical noise, or processing a character too slowly—it would garble all following messages. A single mistake cascaded through everything after it. When this happened, someone had to visit the brokerage and manually resynchronise the machine physically. In a city with hundreds of tickers, this meant a small army of technicians running around Manhattan all day.

Then Edison got involved.

In 1869, Thomas Edison was not yet Thomas Edison, renowned inventor. He was a broke 22-year-old with a knack for mechanical problems who had recently arrived in New York. His breakthrough was a unison device—a mechanism that allowed the master transmitter to send a special reset signal that automatically resynchronised all receivers simultaneously. When he demonstrated the working system, Gold and Stock Telegraph paid him $40,000—about $1 million today—that Edison would use to fund his famous inventions.

By solving the synchronisation problem, Edison made it economically feasible to scale from hundreds of machines to thousands, and from one city to dozens. The time from information creation to consumption dropped dramatically for a significantly larger participant base. By the 1920s, ticker tape was woven into Wall Street’s fabric and expanding on all frontiers. Brokers in any city could instantly access the latest prices. Retail America was quickly integrated into the biggest buying wave yet to hit capital markets8. On busy trading days, the tape would measure in miles.

But miles of paper ribbon spooling out over six and a half hours of trading represented a growing problem. Finding recent prices required brute force. The tape was organised chronologically. Looking for a specific stock at a particular timestamp required manually unspooling the discarded tape, foot by foot, searching sequentially. Looking for price history on multiple stocks was impossible. By 1925, the New York Stock Exchange employed people whose sole job was to collect, sort, and file ticker tape. As volumes picked up in the coming years, it grew increasingly painstaking.

A new asymmetry emerged: the largest participants—investment banks, major brokerages, institutional investors—could afford to build internal systems to manage this chaos. They could marshal resources to organise and query the tape, developing an edge in pattern recognition and informed decision-making. The rest drowned in data they couldn’t effectively use.

Markets were generating more information than humans could organise. Access was no longer the bottleneck, retrieval was. The solution would require ingenuity similar to what created the ticker itself: a unique assembly of existing technologies that, once sufficiently mature, would allow users to search and randomly access the price of any stock in an instant. Right from their desk, with a few keystrokes.

Chapter 4

By 1960, the technology had finally caught up to the need. Jack Scantlin, an engineer who’d spent years studying quote display systems, recognised the opportunity. The core insight was simple: if prices could be stored electronically and appropriately indexed, retrieval could be instantaneous. He founded Scantlin Electronics and built the first commercial stock market terminal—the Quotron.

The device looked unremarkable—a small box with a narrow single-line display sat atop an extended calculator-style keyboard. Yet it accomplished something astonishing. A broker typed a ticker symbol, hit enter, and a few seconds later, the last price appeared. Multiple stock prices could be retrieved in short order. No waiting for tape. No calling the exchange. No searching through filing cabinets. The friction of retrieval collapsed from hours to seconds.

Behind this simplicity lay sophisticated engineering. Quotron conceived precursors to what would become distributed systems and ticker plants. At their datacenter, mainframe computers ingested live ticker feeds from exchanges. These feeds were digitally encoded and transmitted to mainframes installed at client sites, which stored recent prices in magnetic core memory and indexed them for rapid lookup. When a broker queried a symbol, the request travelled to the client’s mainframe, which retrieved the latest price and transmitted it back to the terminal. The dumb terminal itself contained no processing power—just input capability and display. All computation happened server-side.

Despite the complexity of real-time data ingestion, fault-tolerant storage, reliable network connectivity, and manufacturing thousands of consistent hardware units, the product felt easy to use. Even untrained brokers could operate it within minutes. Such easy and instant price retrieval supercharged trading. Trades could close faster with certainty about current market conditions. For exchanges, terminals became essential infrastructure—broad price distribution attracted trading volume, which generated more data, making terminals even more valuable. The flywheel accelerated, setting baseline exchange volumes on a permanent upward trajectory.

By 1970, Quotron dominated US equities while Reuters Stockmaster (using similar technology) owned European markets. Further technical breakthroughs in that decade would seal their dominance.

CRT screens replaced single-line displays, enabling full-page views. Instead of a single ticker symbol showing a single field, screens could display dozens of stocks simultaneously, each with multiple data points—last price, volume, bid-ask spread, daily high and low, all visible at once. Information density exploded.

Distributed network architectures matured. Early systems had one mainframe serving a limited number of terminals, each constrained to sequential queries. Advanced architectures supported thousands of simultaneous users making concurrent requests. Response times stayed consistent even as networks scaled to serve entire firms rather than individual desks.

Most consequentially, terminals evolved from read-only to read-write, transforming OTC markets entirely. Reuters disrupted FX markets with Monitor, allowing currency dealers to enter their bid-ask quotes, which were aggregated and broadcast to every terminal globally. Suddenly, a trader in Tokyo could see real-time prices from multiple London banks simultaneously. Price discovery shifted from bilateral phone negotiations to electronic display—transparent, immediate, competitive. Following the same playbook for US Treasuries, Telerate usurped the fixed income market by the late 1970s.

The fragmentation by asset class was inevitable. Each market had different collection mechanisms: equity prices reported through centralised exchange feeds, OTC bonds required decentralised dealer contributions, and currencies traded bilaterally with no authoritative source. These structural differences meant the three vendors calcified within their respective network effects.

The technical constraints meant only recent price information was feasible to retrieve. Database storage remained expensive and limited. Even by the late 1970s, maintaining comprehensive historical price data for thousands of securities across years was not economically viable. Terminal vendors focused on what mattered most: current and recent prices for active markets.

With price information democratised, the asymmetry shifted to other datasets that were not as easily accessible, or in forms that could not be electronically queried. Financial statements lived in printed annual reports. Analyst research was scattered across brokerage publications. Economic and forecast data were strewn across agencies and industry bodies. Long-term historical pattern recognition remained manual, fragmented, expensive, and the domain of large institutions. Fundamental analysis remained the domain of specialised data collectors like CRSP, Datastream, and Compustat9, accessed through batch processing on mainframes—submit a query, collect results hours or days later.

Meanwhile, financial theory and investor sophistication were rapidly advancing10. Modern Portfolio Theory (1950s), the Capital Asset Pricing Model (1960s), and Black-Scholes options pricing (1970s) were moving from academic papers into practical application. Investors needed to calculate betas, construct efficient frontiers, and model option sensitivities—analyses requiring integrated data across securities, sectors, and time periods.

Heterogeneous information—equities, bonds, FX, real-time and historical, quantitative and qualitative—would need to be served through a single interface. Incumbent architectures were unfortunately pot-committed to a singular outcome: distributing homogeneous real-time data for a single asset class. Building a unified multi-asset, multi-workflow platform meant abandoning the advantages they’d spent decades accumulating and developing a solution from scratch.

Incumbents never build from scratch. Someone else would have the opportunity. Someone who appreciated what Paul Reuter had initially built and understood that, for the evolving trader, the real product wasn’t data feeds; it was decision speed.

Chapter 5

Michael Bloomberg sat at his Salomon Brothers desk in 1980, watching a bond trader lose money in slow motion.

The trader needed to price a convertible—part bond, part stock option. The data lived in three different sources. Bond price and terms from Telerate. Underlying stock price from Quotron. Volatility estimates from internal reports. The trader tabbed between screens, scribbled numbers on a pad, ran some figures in a calculator, and by the time he had an answer, the market had moved.

Bloomberg had lived with this frustration for fifteen years. Salomon Brothers ran one of Wall Street’s most sophisticated bond trading operations, yet even they were flying half-blind. The tools were inadequate, the data scattered, the workflows disconnected. Traders spent more time gathering information than analysing it. When Salomon fired him in 1981, Bloomberg was not yet forty, deeply knowledgeable about bond markets, and convinced the entire information industry was building the wrong product. He ploughed his $10 million severance into building a better terminal11.

The three incumbents shared an architectural philosophy that was their Achilles heel. Their terminal was a thin client—keyboard, screen, just enough processing to send queries and render responses. All computation was performed on mainframes at the data centre. This made sense in 1970 when desktop computing was expensive and unreliable. By 1982, those constraints had shifted. Computers were faster, storage denser, network bandwidths wider, and displays sharper. Oracle had introduced relational databases. Software engineering was maturing as a discipline. User needs had evolved too. Traders no longer wanted to view data—they wanted to manipulate, visualise, model, and act on it.

The first Bloomberg terminal shipped in 1982. From the outside, it looked ordinary. A PC-style terminal with a monochrome monitor and keyboard. Inside, it compounded multiple innovations that made it impossible to compete with.

It stored history. Database technology enabled the efficient storage of indexed, sectioned time-series data. Adding permanent storage required redesigning the entire stack, but it also enabled Bloomberg to reimagine the user experience. Data history enabled analytics, charting, and complex calculations. Positions could be tracked and marked-to-market based on trade history.

It focused on fixed income analytics. Telerate served Treasuries. High notional volume with relatively few issues, and as the risk-free asset, requiring minimal analytics beyond dealer quotes. Bloomberg targeted the rest: high yield, corporates, municipals, asset-backed securities. These were innumerable and required sophisticated analytics—spread analysis, OAS and basis calculations, comparing yield-to-maturity curves. This focus built deep functionality rather than shallow price coverage.

It was visual. They built interfaces around charts and curves rather than text and numbers. Users could see the yield curve’s shape, watch it shift as data arrived, zoom into specific maturities, and overlay historical curves for comparison. No calculators or notepads for checking bond math; it was all computed in real-time and rendered graphically.

It distributed computational power. The terminals were bestowed with edge compute. Analytics ran locally, not round-tripping to mainframes. Response times dropped, making the interface responsive in ways competing systems couldn’t. Because terminals were smart, Bloomberg could deploy them anywhere with a phone line. Reuters and Telerate required installing ticker plants at each client site—large capital expense, long sales cycles, IT approvals, physical space allocation. Bloomberg’s terminals needed no local mainframes. Sales closed in a week. Installation happened the next day. A trader could order a terminal, and it would be deployed before IT knew to object.

It operated on custom hardware. To maximise performance, terminal hardware components were assembled and built-to-spec. While others embraced customer-assembled, off-the-shelf hardware, Bloomberg’s monitor, CPU and keyboard came as an integrated, thoughtfully designed package. The terminal always prioritised the end user’s performance needs over the client’s infrastructure and cost considerations.

The pricing was all-inclusive. No tiered fees, no add-ons, no surprises. Competitors charged base rates plus premiums for historical data, additional exchanges, advanced features. Bloomberg made it simple: all data, all analytics, all updates, all support at one price, capturing all available consumer surplus.

By 1987, with terminals still running in single-digit thousands, Bloomberg was still an outsider. Quotron had 100,000 terminals, and Reuters had quadrupled its market cap since going public a few years earlier. However, neither had access to the profitable and fast-growing market segment that Bloomberg was cornering: corporate bond trading.

Then Black Monday validated everything Bloomberg had built. In October, markets collapsed, volatility exploded, and traders needed information immediately. Bloomberg’s real-time analytics running on its smart terminal enabled real-time decisions while competitors scrambled—phone lines jammed, mainframes queued requests, batch processes ran into the night. In a time of need, while others panicked, the terminal saved seconds and precious capital. The crisis also crystallised something else. Markets were interconnected across asset classes and geographies. Coming out of October 1987, installation requests accelerated faster than Bloomberg could hire sales.

As the ten thousand terminal milestone was crossed, Bloomberg added their own news division in 1990, followed by equities data, derivatives and currencies. All while owning the entire stack: terminal hardware, low-latency high-bandwidth networks, data collection, and proprietary information assets. The Reuters-era verticalisation was reborn, but better - Bloomberg controlled the complete user experience. The terminal, first dismissed by incumbents as too niche, had become the complete information infrastructure for financial markets. For most institutional traders, analysts, and bankers, price was not a deciding factor - you simply had to have a Bloomberg.

At the turn of the millennium, Bloomberg was a multi-asset, multi-domain global platform that integrated market data, news, analytics, messaging, and execution. In its relentless climb, it had long decimated both Quotron and Telerate. By 2008, Reuters, which bought the carcasses of the two dead giants along with other has-beens12 in a desperate attempt to fight back, also succumbed. It folded into a Canadian upstart in the low-tier terminal market, the first in its long journey across foster homes seeking rehabilitation.

My coverage of companies is directly proportional to the number of subscribers from it. Share to get yours covered next.

Yet even as Bloomberg dominated, its premium terminal model had limits. The buy-side didn’t act on real-time data. They needed portfolio construction, performance attribution, and risk aggregation across strategies. Alternative platforms emerged serving these specialised workflows. FactSet focused on fundamental analysis for equity research. BlackRock’s Aladdin provided multi-asset portfolio management and risk analytics. Charles River, SimCorp, and MSCI Barra carved niches in operations and analytics. With its long history of roadkill, none dared compete with Bloomberg on market data.

By 2020, Bloomberg had 325,000 terminals installed globally, generating approximately $10 billion annually. The terminal trivialised access and integration. Information that required multiple vendors and manual coordination was now instantly available through a single interface. Data across geographies, asset classes, and nomenclatures was standardised and uniformly accessible under a cohesive data model.

Despite this success, Bloomberg had missed an entire domain. Its focus was on data that could be structured and systematically queried. Yet a trove of valuable information resisted structure. Millions of pages that couldn’t be queried sat as research commentary in PDF archives. Earnings call transcripts existed, but they weren’t searchable across companies or over time. Alternative non-financial data was barely considered relevant. Yet, smart money was moving to this unstructured realm. Alpha in structured data had vastly diminished, as Bloomberg and its peers had democratised structured financial information13. Alpha had to be uncovered in new domains. In relentlessly pursuing fast-money clients with structured data, Bloomberg had conceded the next era.

Unstructured data would be fought in unfamiliar territory where Bloomberg had the right to play but not the right to win. Distribution, client relationships, technical capability, and ready unstructured archives were negated by over-indexing for structured data pipelines, centralised infrastructure, and rigid terminals. The next wave would be built on cloud storage, distributed processing, and data science workflows running on elastic servers.

The terminal wars were over. The data wars were beginning.

Chapter 6

By 2010, market research and quantitative investing were pushing new frontiers. Freshly stung by the financial crisis, analysts needed hard evidence to verify company narratives. A hedge fund analyst covering Walmart demanded more than management disclosures. Financials were historical. Forward guidance was hard to validate, particularly when estimating the current quarter. The analyst wanted to know what was happening on the ground, across hundreds of Walmart store locations. Not what management claimed in earnings calls, not what Wall Street projected, but whether parking lots were actually full right now, day to day, week to week.

Terminals provided everything traditional: financial statements, SEC filings, analyst estimates, conference call transcripts. They could chart same-store sales, compare inventory ratios, and track margin trends. None of that confirmed if customers were showing up this week, what they were buying, where else they were shopping or where they were coming from. Thousands of people drove to these stores daily. The observational data was trapped in the physical world, waiting to be captured, organised, and queried.

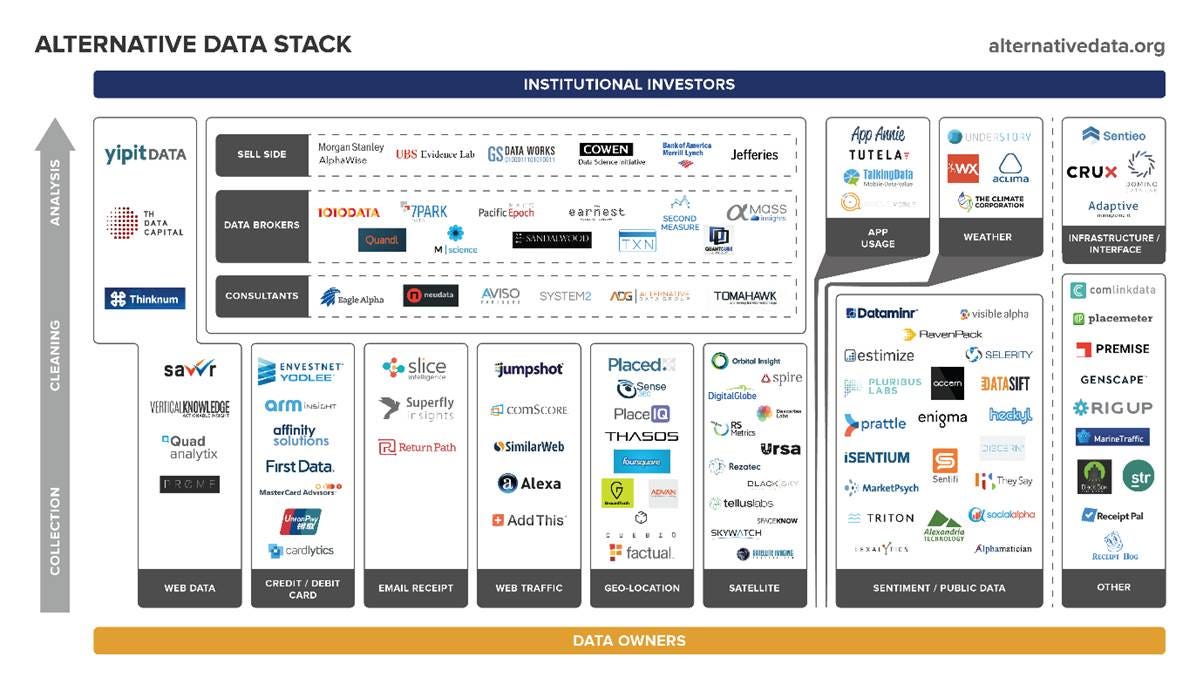

Niche vendors emerged to fill the gap. Some sold satellite imagery to count cars at parking lots. Others scraped e-commerce data to track prices and installs. Few offered credit card transactions across entire payment rails. When parking lot counts diverged from consensus or card data showed strong spending weeks before earnings, funds took positions.

This was alternative data—information orthogonal to traditional financial statements and market prices. It was real-world data, generated by economic activity itself, requiring entirely new sourcing mechanisms that didn’t fit existing data pipelines.

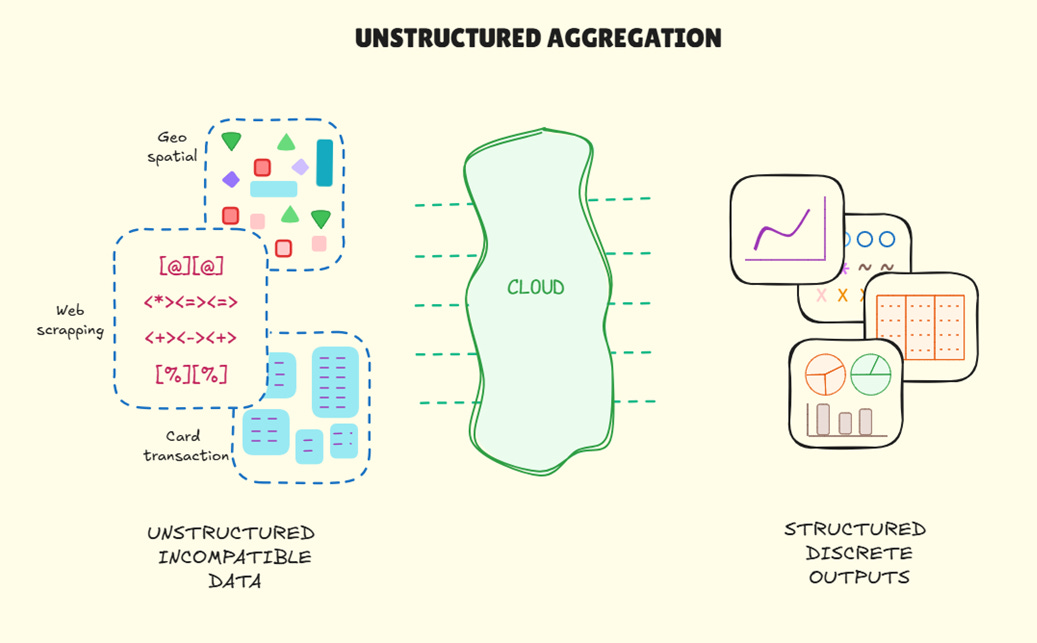

Financial data was structured. Prices came in consistent formats from exchanges. Financial statements followed accounting standards. Everything fit predefined schemas, symbology, and taxonomy that databases could store and terminals could query. Alternative data broke this model completely. Satellite images weren’t structured—they were pixels requiring interpretation. Credit card transactions were difficult to acquire in bulk and presented further complexities with fill-rate timing, code tagging, and debiasing. Web-scraped pricing came in whatever format each website used. None plugged into terminal architectures natively.

The infrastructure enabling alternative data rewrote the old tech stack. Cloud storage made it cheap to store massive raw data indefinitely. Distributed computing made processing terabytes economically feasible. Python emerged with open-source libraries for data manipulation, machine learning, and visualisation. Alternative data vendors could launch quickly once they’d acquired the raw data—no proprietary networks, no manufactured hardware, limited human processing teams, with mostly automated pipelines creating data assets delivered via APIs14.

Despite these advantages, alternative data, the non-textual first half of the unstructured realm, struggled to challenge structured incumbents. In its nascency, it remained expensive to acquire, difficult to wrangle, and often required specialised talent, proprietary algorithms and ready compute to extract alpha.

Satellite providers used computer vision to extract metrics from pixels: counting cars, tracking construction, and monitoring shipping. Credit card vendors aggregated millions of transactions into spending trends by merchant, geography, and demographic. Web scrapers parsed HTML into queryable databases of prices, inventory levels, and job postings. Collecting one dataset didn’t benefit or scale the collection of others15.

The data pipeline after collection, though, was the same: flatten the data, apply statistical models, and extract structured outputs. A satellite image became “estimated weekly foot traffic: 47,250 visitors, +8% month-over-month.” Card transactions became “electronics spending +12%, apparel -3%.” Once the raw data was compressed into a single figure, that figure was identical for everyone. Collapsing the interpretation space through deterministic processing16.

Competitive dynamics followed a predictable arc. As adoption of these datasets spread, signals became consensus, and alpha eroded. By 2020, satellite-derived foot traffic that seemed exotic in 2012 was available on AWS Data Exchange with a few clicks. Alternative data eventually becomes infrastructure—necessary but low-margin, competed on price, frequency and reliability.

The second half of the unstructured realm, textual unstructured data, exhibits entirely different dynamics. The challenge wasn’t collection. It was the ability to query them meaningfully across a corpus of unrelated documents.

In 2011, former Morgan Stanley analyst Jack Kokko and Wharton classmate Raj Neervannan launched AlphaSense to solve this. They’d spent years reading research reports, realising a lot of time was lost finding and manually stitching context across documents. By 2015, they’d aggregated millions of records—sell-side reports, earnings transcripts, SEC filings—and made them semantically searchable with financial context. Users could search for ‘margin pressure’ and retrieve all documents that mention ‘compressed gross margins’ or ‘pricing challenges’ without exact phrase matches. The intent behind the query mattered as much as the query itself. Context and, hence, insights could be stitched across multiple documents in ways previously impossible to surface.

A parallel innovation occurred in expert networks. Traditional networks charged per phone consultation. An investor paid $1,000 for one hour with a former pharma executive. Their insights then existed only in their notes. Tegus instead recorded interviews, transcribed them, and made transcripts searchable. A single expert interview could be monetised dozens of times. Within a few years, tens of thousands of transcripts provided coverage depth that competitors couldn’t quickly replicate17.

In both cases, text data exhibited a unique property. Unlike satellite pixels or card data, which compress into single metrics, text resists deterministic reduction. Three analysts reading the same earnings transcript extract three different insights. One notices capital allocation language changes. Another catches a subtle shift in competitive positioning. A third identifies operational challenges that the CEO mentioned briefly. Their findings diverge because comprehension is interpretive, not deterministic. A research report isn’t reducible to a sentiment score. An earnings transcript isn’t just ‘management tone: positive.’ The value lies in nuance—specific language choices, details mentioned or conspicuously absent, and the context of what else is happening in the industry.

This interpretive diversity means consensus isn’t the default. Lack of consensus meant alpha doesn’t decay as easily as statistically compressed alternative signals. Consuming text data doesn’t require the technical data-science skills that alternative data demands. The perceived alpha is accessible to a much larger market.

Building on their advantage while incumbents slept, AlphaSense acquired Tegus to integrate a dataset that was perfectly complementary. Together, they transformed research workflows. Web-based access from any device. Pricing started at a fraction of Bloomberg’s cost. Thousands of institutions subscribed. Alphasense had stumbled onto a dataset unlike any other, one that resisted alpha decay and naturally replenished alpha potential as the text corpus grew. Alpha truly sensed.

Tapping this alpha, though, had an implicit assumption. The underlying text had to be consumed to be understood. But reading is inherently serial. We process one sentence, then the next, building understanding sequentially. And reading doesn’t scale, so the more content these platforms add, the more overwhelming the volume becomes. Small teams are at a disadvantage compared to firms that house hundreds of analysts.

What was missing was technology that could compress reading time without destroying interpretive flexibility. That could process thousands of documents at machine speed while maintaining nuanced understanding. The asymmetry was about to shift. Textual data awaited a unique compression algorithm. Like the telegraph before it, the breakthrough would come from outside the industry, and the asymmetries it would create would upend a centuries-long pattern.

Chapter 7

October 2025. The conference room at Citadel fills with unease. Ken Griffin has just walked in. Publicly, he has stated that AI cannot produce alpha. His investment committee is about to discover why.

Sarah Chen presents her analysis on precision part manufacturers. She spent the morning using Claude to synthesise 50 expert interviews, 25 research reports, and 15 earnings transcripts. The AI identified three companies showing order-book stress before it appeared in their financial statements. She has reviewed the reasoning and citations—the analysis is sound.

David presents next. Same data sources, with different prompts to GPT-5. Opposite conclusion: the stress signals are regular cyclical inventory adjustments, not demand weakness. His analysis is equally rigorous, equally well-sourced.

The investment committee sits in silence. Both analyses are defensible. Both are grounded in evidence. AI didn’t make either of them wrong; it made both of them possible. This has never happened before. Previous eras built infrastructure in which information compression was deterministic. The telegraph transmitted identical messages to all recipients. The terminal organised identical data for all subscribers. Same input, same output, universally.

AI breaks this pattern completely. LLMs are probabilistic by architecture. They vary outputs through user choices—prompt design, context provided, and unconscious biases. Variation we’re accustomed to. They also vary through hidden parameters such as temperature settings, attention mechanisms, context windows, and training biases. Variations invisible to us. Hence, the same document with different prompts produces different conclusions. Identical prompts with different models produce divergent interpretations. Non-determinism is the design.

Our ability to evaluate these interpretations or insights, however, remains fixed. A portfolio manager needs to know which analyses to trust, which interpretations match reality, and which should guide capital allocation. This requires judgment, the residue of iteratively learned experience—domain knowledge about what matters in supply chains, market intuition about what consensus is missing, creative thinking about questions others haven’t asked, self-awareness about where assumptions might be wrong. These aren’t qualities that can be fine-tuned like parameters or scaled through capital expenditure18.

Previous cycles expanded information supply—more prices, more venues, more data types. This cycle expands the supply of insights without expanding evaluation capacity. As LLMs grow more sophisticated, they generate more plausible-sounding analyses, expanding the space of defensible-but-wrong interpretations. Our serial reading constraints, when applied to this generated token volume, only compound the need for high-quality evaluation infrastructure.

Evaluation addresses only half the equation—ensuring outputs are correct and conclusive enough to build a thesis. The other half is orchestration—ensuring inputs are complete and co-ordinated enough for AI to find novel insights.

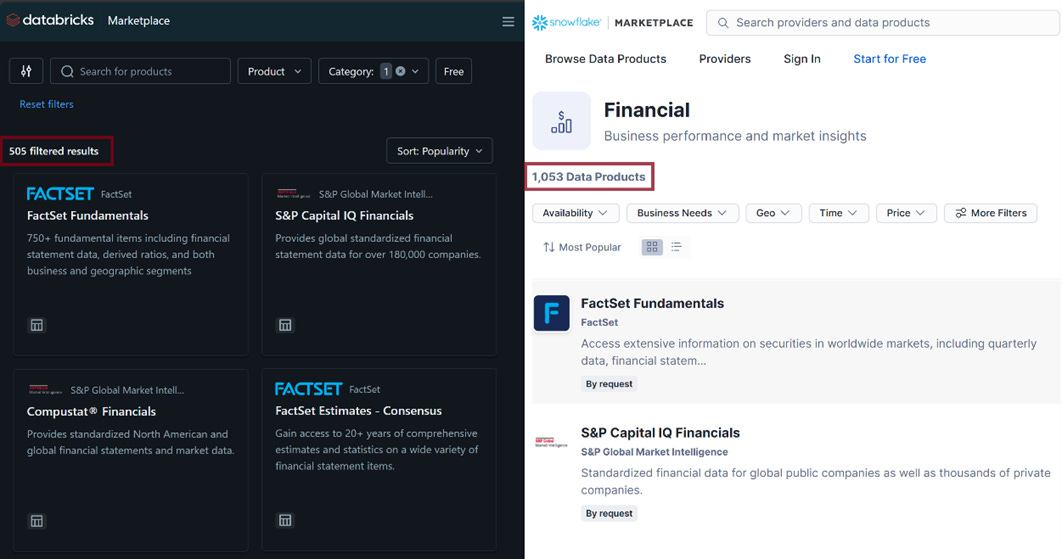

AI can only interpret what you feed it. Missing information across inputs varies conclusions, regardless of how well-designed your prompts are. An analysis using Claude on a single vendor’s data, thin on non-GAAP metrics, arrives at a different view than one using Gemini on FactSet fundamentals enriched with S&P credit data and a proprietary expert network. While the access gap existed in the pre-LLM world, AI dramatically multiplies its effect.

AI’s superpower is multi-domain synthesis—identifying patterns humans cannot see, generating interpretations spanning ultra-long contexts we cannot mentally integrate. However, that superpower is hamstrung when data remains fragmented across competing vendors or internal silos.

Consider some of the inputs required for an informed view of current tech valuations: Nvidia’s earnings calls, hyperscaler capex guidance, semiconductor supply chain analysis, private credit reports on datacenter financing, power generation capacity studies, and even Altman’s podcast transcripts. An analyst must manually synthesise across multiple subscriptions with incompatible formats, stitching together disjointed data, tables, and charts. Access to only a selection of sources creates varying blind spots. And without sufficient breadth of data access or unique investor context, an LLM cannot generate sufficiently novel insights.

Further, insufficient and illegible inputs increase the likelihood of (multiple) wrong outputs. And when outputs of one prompt feed the inputs of the next, the two become co-dependent. In iterative reasoning across multiple models, this dependency can degrade—sometimes gracefully, but usually rapidly—across long context windows. A sliver of signal instead generates an avalanche of amplified noise.

Markets have always rewarded sophisticated institutions that can counteract this information loss. That can separate signal from noise and process more data faster. AI compresses those volume and speed asymmetries to near-zero. Anyone can now analyse hundreds of documents at machine speed. They can also generate multiple plausible yet inconclusive hypotheses. The constraint now is no longer data or insights. It’s stitching together unique information assets and replicating learned judgment.

Like the telegraph needed the ticker to scale distribution, AI awaits orchestration and evaluation infrastructure to improve decision quality. Doing so successfully requires counter-positioning, which in information markets is architectural. The ticker won by inverting the telegraph’s topographical limits—from point-to-point to broadcast. The smart terminal won by inverting the dumb terminal’s constraints—from centralised computation to distributed power. Alternative data vendors endured by inverting terminals’ economics—from proprietary infrastructure to cloud-native pipelines. The opportunity for the next cycle rests on a similar inversion.

The Grossman-Stiglitz paradox dictates that financial markets require some information asymmetry to function.

Seven chapters have traced what happens inside this paradox: compress one friction to reveal asymmetry in the next. Scribes eliminated ephemerality, asymmetry shifted to geography. The telegraph collapsed distance, asymmetry shifted to continuity. Tickers enabled broadcast, asymmetry shifted to retrieval. Early terminals solved retrieval, asymmetry shifted to integration. Bloomberg integrated structured data, asymmetry shifted to unstructured sources. Alternative data vendors solved access to text, asymmetry shifted to interpretation. Each cycle, the same underlying motion—so consistent it seems less like pattern than law.

Every winner profiled here also served a common purpose. Each took information scattered across space, time, or format—and collapsed it into unified, legible systems. Reuters corralled scattered geographic prices into unified feeds. The ticker channelled discrete messages into continuous streams. Quotron indexed chaotic tape into instant retrieval. Bloomberg unified fragmented data types into integrated terminals. AlphaSense imposed semantics on unstructured text.

Chaos to order. Disorder to structure. Fragmentation to unification. Each channelled new technology to reduce information entropy. The playbook never changed.

Until now.

With AI, entropy can be generated, harnessed and exploited to increase decision quality.

What if instead of two analysts arriving at two interpretations, Citadel deployed a dozen AI agents—each with different analytical frameworks, different prompts, different model architectures—to explore the same question simultaneously? One agent adopts the lens of a supply chain sceptic. Another models the bull case for cyclical recovery. A third stress-tests management credibility against historical guidance accuracy. A fourth focuses purely on balance sheet risk, and so on19.

Within hours, the committee sees eight agents converging on three risk factors. Two surface concerns about a supplier relationship that no analyst caught. Another uncovers the full list of contradictory assumptions embedded across responses. By forcing explicit exploration of multiple plausible paths, the agents surface ideas that a first read would conceal. Where do interpretations converge? That’s likely signal. Where do they diverge? That’s where assumptions need stress-testing. What did multiple agents flag that a single analyst missed? That’s where blind spots live.

What was previously anchored by a single conviction is instead evaluated against the full range of valid interpretations. The evaluation layer channels AI’s inherent multiplicity to improve decision quality. Entropy generated and harnessed.

Improving decision quality isn’t limited to output evaluation. Input orchestration also offers an opportunity.

A challenger cannot out-aggregate Bloomberg or its peers. Instead, it has to preserve vendor fragmentation while making it seamlessly navigable for AI to interrogate across domains and sources. When queried about a retailer’s unit economics, an orchestration tool should enable an LLM to autonomously discover that foot traffic data (from vendor A) shows visits up 12% year-over-year, while credit card data (vendor B) shows same-store transactions down 3%. It reviews expert network transcripts (vendor C) to identify the cause - the retailer is gaining traffic but losing transaction size as customers trade down to lower-priced items. It realises sell-side estimates (vendor D) bake in strong holiday buying based on traffic uplift, while supplier surveys (vendor E) show cautious restocking patterns. It surfaces aggregated findings and recommendations for next steps for the user to continue their research.

No single source holds enough conviction; together, the AI crawls vendor documentation and datasets to integrate and synthesise novel insights to aid the investment process. Improving decision quality through diversity and discord. Entropy identified and exploited.

Raising decision quality on both sides displaces the old incumbent value chain. Stitching inputs across vendors shifts value from proprietary data ownership to cross-vendor intelligence, from trusting one source to verifying across many, from depth within silos to insight across contradictions. Evaluating outputs shifts value from speed of analysis to quality of interpretation, from processing documents faster to judging interpretations better, from consensus views to personalised conviction maps. Displacements that all run contrary to incumbent incentives and infrastructure20.

But not contrary to information market economics.

Strip away the technology—telegraph, ticker, terminal, transformer—and what remains is a business model so fundamental it has persisted from barley fields to trading floors. Mara’s deepest insight wasn’t about price differentials. It was understanding that financial markets have a perpetual need to reduce information asymmetry. And those that build the infrastructure to minimise it across market participants capture enduring value.

History shows us that is where fortunes get built. That’s where it always gets built21.

After all, asymmetry is all you need.

The Terminalist.

h/t to Dan & Didier for feedback on this post.

Asymmetry offers an interesting lens to view financial markets. If you enjoyed this post, like and subscribe to follow my (free) exploration of how data and information contribute to capital markets. Comment so others can learn from your perspective and share (via email or LinkedIn) so you have someone to discuss it with.

Do nothing, and you’ve resigned me to die in the ocean of unstructured text.The opportunity to build has never been greater, but attention is scarce and capital impatient. If you’re exploring the frontiers of how AI can be harnessed at any stage of the financial data value chain and think I can be helpful, get in touch. My DMs on Substack and on LinkedIn are open if you’d like to discuss an opportunity, debate hot topics, or get involved in future posts. If X is your jam, connect here.

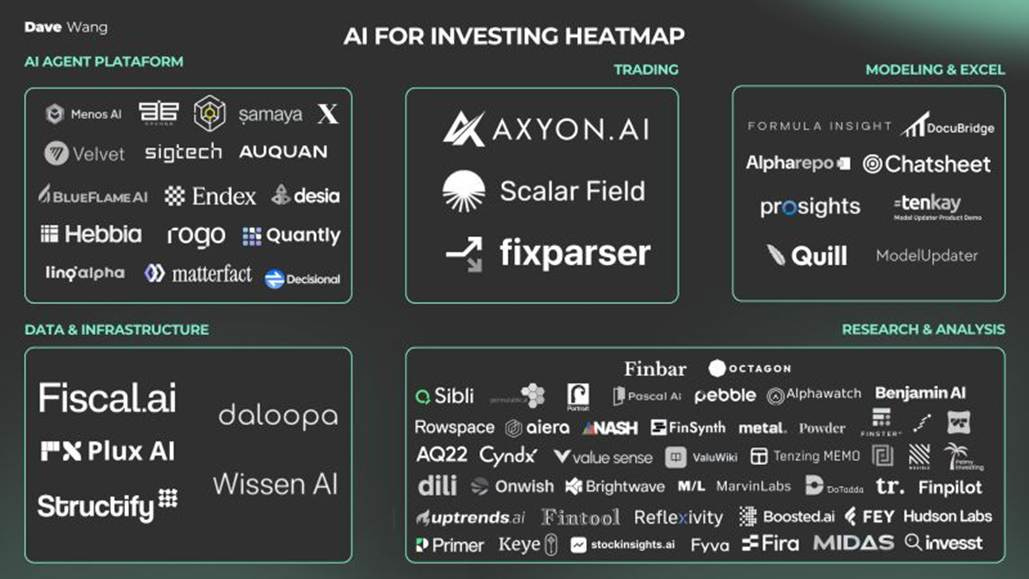

Market maps face the same competitive pressures as financial data – granularity, coverage, completeness, refresh frequency, etc. Unperturbed, the (full-time meme comic and part-time) founder of AggKnowledge, Dan Entrup has swung for the fences. Do check out his nearly 2k comment homerun. If you enjoyed that breadth of coverage, subscribe to his excellent newsletter to stay on top of everything happening across financial data – M&A, funding, hiring, people moves, reading lists, etc.

Our community has crossed 5,000 subscribers in its first year. Thank you for your patronage of my curiosity and for indulging in long-form content. Next year, expect a few interesting additions to how The Terminalist delivers value to readers and the ecosystem of participants they represent. On the publication end, I’ll cover more company deep dives, new-entrant profiles, and industry history, while interrogating ideas and executives old and new.

For more deep dives to add to your Xmas reading list check out my popular posts from earlier this year.

The definitive guide to Bloomberg’s competitive moats that allows it to dominate the market.

The invisible yet powerful smiling curve that shapes value creation across the industry (covering CME, Factset & MSCI).

A look at why financial data is so lucrative, and how data is converted into dollars by exchanges, distributors, indices and ratings agencies.

How AI & LLM capabilities are redefining the competitive frontier outside of the traditional market data terminal.

A contrarian look into LSEG’s acquisition of Refinitiv and how it has played out so far.

In the meantime, as we draw towards the new year, happy and restorative holidays to all. If you would like to get me an X-mas gift, I’d love for Matt Levine or Andrew Ross Sorkin to be my editors. Introductions welcome.