Once icons of corporate uniformity, abandoned Wal-Marts in Kentucky now host thriving community flea markets.

BeeLine Reader uses subtle color gradients to help you read more efficiently.

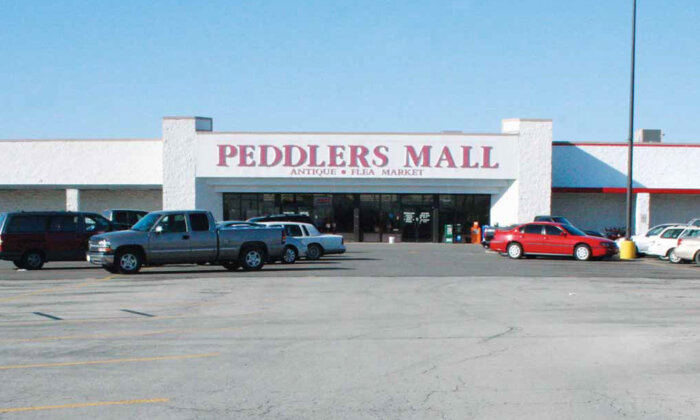

“Sometimes Wal-Mart’s new shopping carts roll right down the hill and get mixed into our mess of buggies,” says Kathy Clem, manager of the Peddler’s Mall in Nicholasville, Kentucky. The Peddler’s Mall is reusing the old shopping carts that have always been pushed around this building, which was once the first Wal-Mart in Nicholasville. The new Wal-Mart sits directly across the street, at the top of a hill. The staff at the Peddler’s Mall returns the shopping carts to the retailer, and they make jokes with the Wal-Mart managers about the carts being confused about which building is home. The carts are not cheap, after all, at roughly $120 apiece.

The Peddler’s Mall slogan contends that it is “more than just a flea market.” Considering that the store is actually a chain of 15 stores, it is more accurate to say that the Peddler’s Mall is more than just 15 flea markets. The chain of secondhand stores is the brainchild of Kentuckian John George, who hit upon the idea of renovating big box stores to open up the flea markets in the mid-90s after he had just lost his entire business in the textiles industry. George had owned three factories in Kentucky that made clothing: a screen-printing factory in Louisville, and two factories for cutting and sewing in nearby Lebanon, Kentucky. The operation had big contracts. In the 1990s, all of those contracts went overseas. The factories lost everything and went bankrupt, and he lost his factories to the emergence of the offshore textiles economy.

Ironically, George soon learned of the empty Wal-Mart buildings across Kentucky, and he began to formulate the idea of opening flea markets inside the abandoned stores. The Peddler’s Mall website states, “Wal-Mart Realty is the primary landlord of the Peddler’s Mall. As Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. expands and diversifies their stores into Wal-Mart Supercenters and Neighborhood Markets, additional opportunities could become available.”

The Peddler’s Mall network has over 3,000 vendors selling their wares under the roofs of what were once monolithic superstores.

The abandoned buildings seemed to be everywhere in Kentucky. George had previously run a flea market in Pinellas Park, Florida, on U.S. 19, so he had an idea of how to get a vendor’s mall together. He called Wal-Mart, and to his surprise, the company was pleased to help him get started. His flea market would not pose any competition to the corporation, and no major changes needed to be made to the buildings. He was basically just moving new merchandise into the buildings, creating new superstores in the footprint of the stores that were already there. He opened his first Peddler’s Mall in 1997.

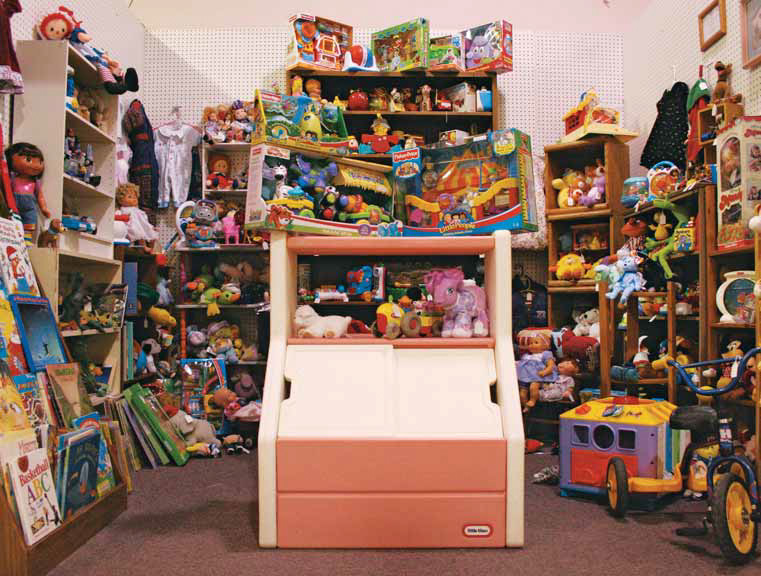

“The concept is recession-proof,” George tells me. “People will always buy recycled items.” And there is never a shortage of people with secondhand items to sell. The Peddler’s Mall network has over 3,000 vendors selling their wares under the roofs of what were once monolithic superstores. A stark contrast exists between this marketplace and the monolithic structure in which it resides. It is as if the Peddler’s Mall has detected a small hole in the big box system, the vacant stores, and has inserted a retail system within it that seems almost subversive, given the context.

The business plan is simple: George rents the buildings and draws a grid in the interior of the retail space. The “peddlers” then rent the individual spaces from him to vend their wares. Customers pay at a central cash register at the front of the building at the old Wal-Mart’s checkout counters. George had a computer system developed that keeps track of each vendor’s sales, and they receive biweekly paychecks from the Peddler’s Mall. Each vendor keeps 98 percent of what he or she sells, and he takes 2 percent to cover credit card fees, electricity, and other small costs. “Everyone makes money!” says George. The Peddler’s Mall chain employs over 85 people, and the peddlers collectively use over one million square feet of retail space.

I traveled around Kentucky to visit three of the sites, all of which are Peddler’s Malls in renovated Wal-Mart stores: Hillview, Elizabethtown, and Nicholasville. In the past, George operated five other stores in abandoned Wal-Mart buildings. In all of his dealings with Wal Mart, a third party owned the buildings, and Wal-Mart owned the lease on the structures. He typically rents the lease from Wal-Mart until it runs out, when control of the building defaults to the real estate company who was managing the lease. Then the Peddler’s Mall moves on. George feels as if he has had great luck with Wal-Mart, and says that he has fallen into a great fortune. He reports that Wal-Mart makes the subleasing as “soft as they possibly can, and they are not making any money on my subleases.”

The buildings I visit are indeed old Wal-Mart buildings. They are not in very good shape, but they are good enough for the business at hand. My first Peddler’s Mall is the site in Hillview, a part of Louisville, where the Wal-Mart stripes still run around the border at the top of the store. On the way out of the building is another Wal-Mart relic, the imprint of the words “Thank you for shopping at Wal-Mart” on the wall above the door, where that entire slogan once appeared in blue and white letters. Here at the Peddler’s Mall, though, the word “Wal-Mart” has been knocked off the wall, and simply replaced with the words “Peddler’s Mall,” so that the slogan and sign have been adapted: “Thank you for shopping at Peddler’s Mall.” Brenda Thompson, the manager, tells me that “the Wal-Mart folks really loved that.”

The Hillview store, which opened on August 1, 2001, has 338 different vendors. Approximately 225 vendors run the booths, some of whom rent more than one spot. “Some of the vendors are cleaning out a garage or a basement, and are only here for a month,” Thompson says. But others are here for the long haul; some even make a living by operating booths in the Peddler’s Mall. About 50 percent of the vendors here have been here for over a year, and there is currently a waiting list a hundred names long to get a booth in the building. George says that the vendors, on the whole, pull in about $3 a square foot throughout the entire operation.

The Wal-Mart superstore across the street attracts shoppers, which is always promising for surrounding business. George, who has rented 10 empty Wal-Mart stores over the years, says that in eight of his experiences, Wal-Mart has moved directly across the street from the store they are abandoning. “It is perfect when Wal-Mart moves in right across the street. That is what I am always hoping for,” says George. Thompson tells me, “This is where people go before they go to the Wal-Mart across the street. Sometimes you can find the same items for sale here that are cheaper than they are across the street at Wal-Mart. Might as well check to see.”

Although many of the booths sell typical flea market items, antiques, and novelties, some booths sell pallets of toilet paper or diapers, items that the Peddler’s Mall vendor picks up at outlet retail centers that sell overstock on various items for incredibly low prices. “There are also antiques here, and good, well-made secondhand items. People come here if they want an inexpensive dresser made out of real wood, instead of a new dresser from Wal-Mart that you have to put together yourself,” says Thompson. Thompson has lived here off the Preston Highway for 28 years; she moved in long before Wal-Mart did. This was one of the first Wal-Mart stores in Louisville, a city that now hosts 12 stores, including Wal-Mart’s Neighborhood Markets.

Traffic from the retailer has completely changed this area of town, which is now a highly developed commercial area. The new Wal-Mart, she says, is inconvenient, is too big to navigate, and attracts too much traffic. “It used to be such a smooth drive from my house to Wal-Mart, and the new store causes me to go through so many new stoplights.” Thompson is interrupted by a customer looking for a fireplace liner. She knows exactly which booth he should check.

I drive the 45 miles to the next stop, the Elizabethtown store. The building is on a long strip of development, and this is apparently a very old Wal-Mart store. Elizabethtown is a small city in the center of several very rural towns: Radcliff is about 15 miles north, and Fort Knox is about 10 miles to the east. This Wal-Mart store had been the only franchise within 30 miles or so before the company expanded to open several stores across central Kentucky; the next one over was in Bardstown, about 30 miles to the east.

Beverly Beavers, the manager at this store, is quick to point out the carpeting on the floor. Half the building’s floor is covered in red carpet. She says that when the first Wal-Mart stores came to Kentucky, the clothing and jewelry sections were carpeted. “They save their money today,” Beavers says. “No carpets.” The racks were low here too, so that you could see over them, and socialization would occur.

Along similar lines, Dixie Hibbs, mayor of Bardstown, once told me, “Those old Wal-Mart stores allowed people to socialize. You could see over the racks and the shelves, people talked to each other. The new supercenter in town is geared for tunnel vision, tunnel shopping. You go in, get what you need. You are only distracted by the other hundred things in your line of sight that you feel like you need to buy.”

In that same conversation, Hibbs tells me about the evolution of stores in Bardstown, and while I was visiting these flea markets throughout the state of Kentucky, that conversation kept echoing in my mind. “Downtown,” she says, “has gone through cycles with its stores. In the early 1800s, all of the shops were separate. The bonnets were made in one store, the horseshoes were made in another store, people bought tools in another store. Goods were made in back and sold up front. As the supply and demand increased, goods began to be produced off-site. The factory was a block or two from the town square in a larger space, and the goods were brought to the store, which remained right downtown in the shopping district.

In the 1850s, stores in Bardstown began to expand to include more than one type of good per store, starting with the drugstores. These were the first shops to carry items other than their main product, medicine. In the late Victorian era, stores began to expand again and include showrooms; items were made in the back in enlarged backrooms, and the items were shown for sale in the front. This era brought the makers and the sellers back under one roof. Eventually more than one vendor sold items out of the same store.”

These new stores house not only retailers, but “peddlers” — an archaic term that links the operation to the markets of fairytales.

Stores returned to selling one major good in the early 1900s, with one main storekeeper under each roof. Hibbs fits big box stores into this lineage. “The big box empire marks an era when the major retailers are corporate retailers who are not locally based. These retailers actually sell every kind of good, and those goods were not only made offsite but offshore, in another country altogether.”

Traveling around Kentucky to visit these flea markets in the renovated big box stores made me ponder this cycle. While these buildings previously housed the monolithic big box retailer, these new stores house several retailers selling their wares under the same roof — not only retailers, but “peddlers,” an archaic term, linking the whole operation to the markets of fairytales. These wares are also not necessarily made locally; many of these booths sell the same items that you can get across the street at Wal-Mart. The memory of their origin has been lost.

My next stop is the Nicholasville store, near Lexington. This is where I meet Kathy Clem, manager of the store since the day that it opened in 2002. “I learn a little more every year about how to run this business,” she says. “I have never had a job like this — landlord for hundreds of people, organizing their sales, and keeping the building in shape.” Clem’s first job was at a Wal Mart; she worked at the store in nearby Winchester when she was 16 years old. That store is now a Peddler’s Mall, too.

There are 270 booths here, plus 20 cases in the front for vendors who sell jewelry or other small items. When the Peddler’s Mall building has a problem, management simply calls up the local Wal-Mart “assets manager,” who then sends a local “super” or subcontractor to fix the problem. “Leaky roofs, potholes, the Wal-Mart group comes out and takes care of it,” Clem says. The other maintenance issues at the Nicholasville store are taken care of by Clem and her family. “My kids and I keep the place clean.”

Clem loves her job. She says that these aisles are filled with memories. “I saw a replica of the very bedroom set I had as a little girl the other day in aisle seven. Gave me goosebumps.” Recently a woman came into the store looking for interesting plates to add to her own collection of antique plates. She got into the hobby because her grandparents also collected plates, and they had a peculiar practice of cutting a little piece out of their clothing and gluing it to the backs of the plates. This plate shopper was going through a box of plates in an antique booth recently when she found her grandparents’ plates. As Clem tells it, “The clothing was glued to the back. She came up to the front booth crying tears of joy. Those plates that she knew when she was little — the very plates that inspired her to begin her own collection — she found them.”

Clem claims the moneymaking aspect of the business is exciting. “If you want to make money, you can.” Surprisingly, George, the vendors, and the employers are not the only parties privy to the profit — the city makes money, too. Clem tells me, “Each time a vendor opens a booth, they have to pay the city $15 for a business license. Although roughly 60 percent of the booths are mainstays who never leave, 40 percent of those booths turn over almost monthly. Every time there’s a turnover, the town makes 15 bucks.”

There are endless products for sale here, ranging from nice old handmade Kentucky quilts to plastic toys made in China distributed by a wholesaler. Clem says the most successful vendors are the ones who sell a variety of goods in one booth. If a shopper comes in to buy a record, then sees diapers there and maybe a back-scratcher and a novelty candle, he or she will pick up a little of everything. “People like to do the one-stop shopping. People grew up in Wal-Mart, they are used to finding all the items in one place, and that carries over to this business too,” contends Clem.

She says she reminds people that this place is “just like Wal-Mart” when they are not sure how something works. If a customer asks if he or she can put something on layaway, she says, “It’s just like Wal-Mart,” meaning layaway is not a service offered by the store. When people ask where the bathrooms are, she says, “It’s just like Wal-Mart,” meaning the bathrooms are in the back by the employee’s break room. The building is completely the same as it was in its life as a Wal-Mart, save for an interior paint job and the destruction of one wall that separated the store from the small storage space. “We want the buildings to be entirely retail,” says George. “No storage here at all. Just bring in your goods and put them on the shelf. We want as much space for retail as we can get.” Just like Wal-Mart.

We are passing down our way of life to our descendents in the form of the built environment that we create and leave behind.

While I was driving around the state visiting these buildings, I stopped by Bardstown to visit my family, and one day I met with Kim Huston, president of the Nelson County Economic Development Agency (NCEDA), to hear about the local big box updates. I tell her about the final chapter in my book, about the Peddler’s Mall. She smiles at me, and then tells me, “Remember the Wal-Mart building that we tore down to make room for the courthouse?” Of course I do, the first chapter of my book is about that site. “The last use for that building was George’s very first Peddler’s Mall. He was there when the roof leaked, and people would go shopping with umbrellas. There were people in Bardstown, however, who felt his business did not exactly fit in with the historical integrity of our town. It was 2002 when he left the Wal-Mart building so that we could get started on the Justice Center.”

Big box buildings are developing histories right now, despite our warped hope that these structures will just go away once they are vacant for long enough. The reality is that we are developing history every day — even at vacated global retail sites — while our attention span shrinks, and the “now” grows shorter. Our actions will not be hidden from our descendents; rather, we are informing the way they will live too. We are passing down our way of life to them in the form of the built environment that we create and leave behind. There is no easy way out, there are no wormholes for us to jump through.

Like it or not, time keeps moving, and we are all a part of what will come next. In our networked world, where time and space are collapsing under the influence of wires, modems, monitors, and satellites, it is indeed revolutionary for us to look to our local realities, in order to fluidly connect with what is happening around us. It is also revolutionary for us to intervene in the existing built environment, to rethink what is on the ground, to recontextualize the realities in our own backyards.

Embracing the continuous passing of time will lead us to perpetuate ground-truths that are congruous with our needs, our desires, our hopes, and our dreams. The future is, of course, imminent every moment. We are evolving into that enigmatic state of time right now, with every word.

This gives us an opportunity, every minute, to be revolutionary.

Julia Christensen is a multidisciplinary artist whose work explores systems of technology, consumerism, landscape, and change. She teaches at Oberlin College, and is the author of “Big Box Reuse,” from which this article is excerpted.