On February 18, 2016, nearly four dozen family members and friends filled a federal courtroom in Wilmington, Delaware, waiting for closure. They came seeking justice. When the sentences were read, there was relief in the room. The judge imposed the maximum—life in prison.

But outside the emotional gravity of the moment, a quieter and more unsettling question lingered, one that has never been adequately addressed in public discourse: How does a non-violent cyberstalking conviction result in a life sentence in the United States of America?

This article is not an attempt to relitigate grief, nor to diminish the horror of what occurred at the New Castle County Courthouse in 2013. Two women were murdered. A family was shattered. A community was scarred. Those facts are not in dispute.

What is in dispute is how the federal justice system extended culpability, punishment, and precedent in a way that appears without parallel in modern American law.

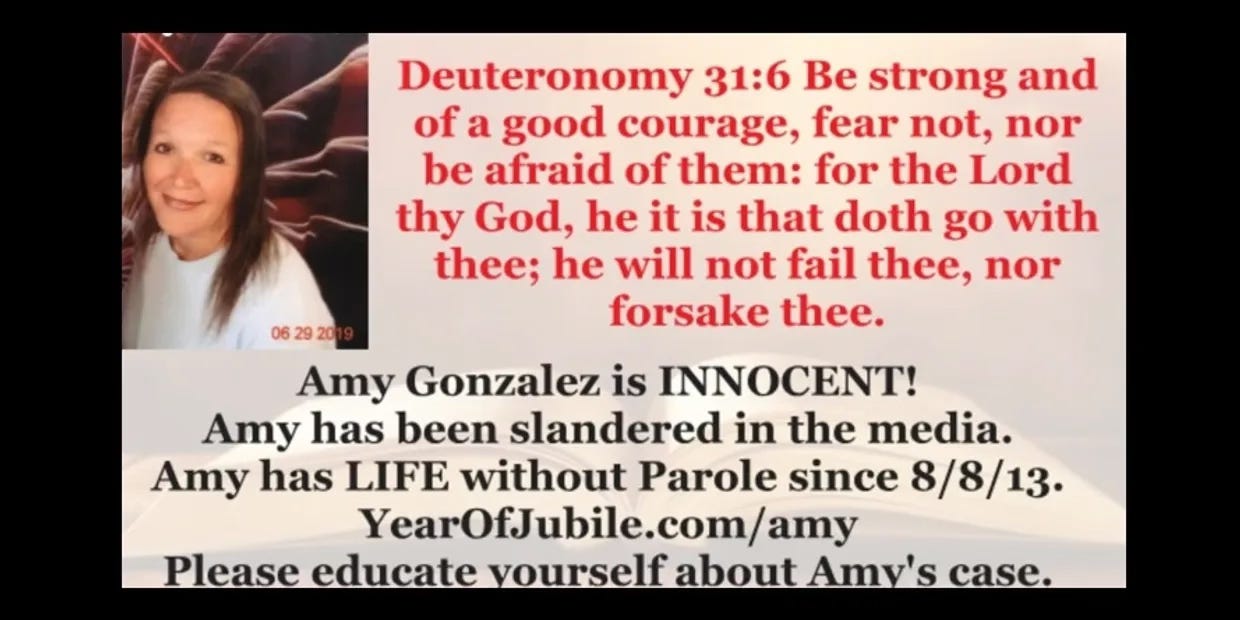

At the center of that question is Amy Gonzalez.

On February 11, 2013, Thomas Matusiewicz entered the lobby of the New Castle County Courthouse in Delaware and fatally shot his former daughter-in-law, Christine Belford, and her friend, Laura Mulford. Moments later, he took his own life. The killings were immediate, shocking, and indisputable.

Thomas Matusiewicz was the shooter. He acted alone. No one else fired a weapon. No accomplice assisted him in the courthouse. That much is clear. What followed, however, would stretch criminal liability far beyond the trigger.

In the aftermath, federal prosecutors charged Thomas Matusiewicz’s adult children and his wife, not with murder, but with cyberstalking resulting in death, conspiracy, and interstate stalking. Among them was Amy Gonzalez, Thomas’s daughter.

Amy was living and working full-time as a registered nurse in Edinburg, Texas, at the time of the shootings. She was not in Delaware. She was not present at the courthouse. She did not participate in the attack. She did not commit a violent act.

In 2015, a federal jury convicted Amy Gonzalez of cyberstalking-related offenses. In 2016, she was sentenced to life in federal prison. Because the federal system does not offer parole, life means precisely that.

To date, no other cyberstalking case in America has resulted in a life sentence. That point matters, not rhetorically, but legally.

According to Gonzalez, her case is the first of its kind not only in Delaware, but in the entire country. A precedential case. One that expanded the interpretation of “resulting in death” to a degree that critics argue collapses the distinction between speech and homicide.

Federal law does allow for enhanced penalties when stalking behavior leads to death. The intent of that statute was clear: to address direct, sustained harassment that drives a victim to suicide or places them in imminent danger.

The application here is different. The deaths were caused by a third party, who then committed suicide. That third party, Thomas Matusiewicz, was diagnosed with meningiomas, brain tumors located on the left frontal lobe, an area associated with judgment, impulse control, emotional regulation, and aggression.

No expert witness testified at trial on the behavioral or psychological impact of those tumors. The jury received only a stipulation noting their location and size. That absence remains one of the most contested aspects of the case.

The prosecution’s theory rested heavily on online videos, statements, and alleged coordinated harassment tied to family court disputes years earlier. Amy Gonzalez has consistently maintained that posting a video or participating in online speech cannot reasonably be equated with causing a double homicide. She was never offered a plea agreement.

According to her account, her attorney did not attempt plea negotiations and insisted on going to trial. She was tried alongside her brother and mother, despite differing locations, actions, and roles.

The jury ultimately returned guilty verdicts. Then came sentencing.

Perhaps the most disturbing chapter came weeks later.

Amy’s mother, Lenore Matusiewicz, was sentenced to life in prison while hospitalized, ten days after undergoing emergency brain cancer surgery. Audio of that sentencing has circulated online. She died less than three months later, on Mother’s Day weekend in 2016. The speed of that sentencing ensured a grim distinction: the first person in America sentenced to life imprisonment for cyberstalking.

That distinction would soon be shared.

Amy Gonzalez has been incarcerated since August 8, 2013. She is now 52 years old. She is a registered nurse, licensed since 1992. A breast cancer survivor. A wife. A mother of two children who grew up while she remained behind bars. She has never been convicted of a violent crime.

Her federal case number is 1:13-cr-83-GAM-3, United States District Court for the District of Delaware.

Her sentence is life.

Supporters of the verdict argue that relentless harassment created conditions that led to violence. Critics counter that the ruling establishes a dangerous precedent: that speech, association, and family conflict can be retroactively transformed into homicide liability when tragedy strikes.

If that line holds, it does not stop with this case. That is why this matters beyond one family, one courtroom, or one state.

This is not about sympathy. It is about proportionality, due process, and the boundaries of criminal law.

Amy Gonzalez currently has a Rule 60(b) Motion alleging fraud upon the court pending. Her pro bono paralegal, who assisted in preparing that filing, passed away unexpectedly in December 2023. She is asking for help. Not blind allegiance, but examination. Scrutiny. Transparency.

Please check out the audio podcast we released this morning. You will hear a judge giving Lenore Matusiewicz a life sentence while in the hospital, three months before she passed away. You will also hear audio from Amy that was recorded on December 16, 2025. That audio will speak for itself.

This article exists for one purpose: to place the facts, the claims, and the consequences in front of the public, and to ask the question the court system already answered, but never fully explained. Does justice still mean individual guilt, or has it become something else entirely?

My closing thoughts: Speech, association, and online conduct were legally stretched until they carried the same weight as homicide. Whether you agree with the verdict or not, that precedent should disturb anyone who believes punishment must fit the crime. What they did do was set a precedent for what is to come. God bless all involved and their families & friends.

**Special thanks to Rudy Davis of Year of Jubile for amplifying Amy’s case and keeping public attention on her situation when most outlets moved on. Rudy also worked tirelessly to help gain Jeremy Brown’s pardon in 2025.

Listen To Amy & Lenore speak here: https://www.spreaker.com/episode/episode-387-life-without-a-violent-act-the-amy-gonazlez-story--69124446