The Nutgraf

Edition #221 • Saturday, 16 March 2024

A personal story about the water crisis in Cape Town and how it contrasts with what’s happening in Bengaluru

A personal story about the water crisis in Cape Town and how it contrasts with what’s happening in Bengaluru

A paid 🔒 weekly emailer that explains fundamental shifts in business, technology and finance that happened over the last seven days in India. In a way you’ll never forget. Someone sent you this? Sign up here

Good Morning Dear Reader,

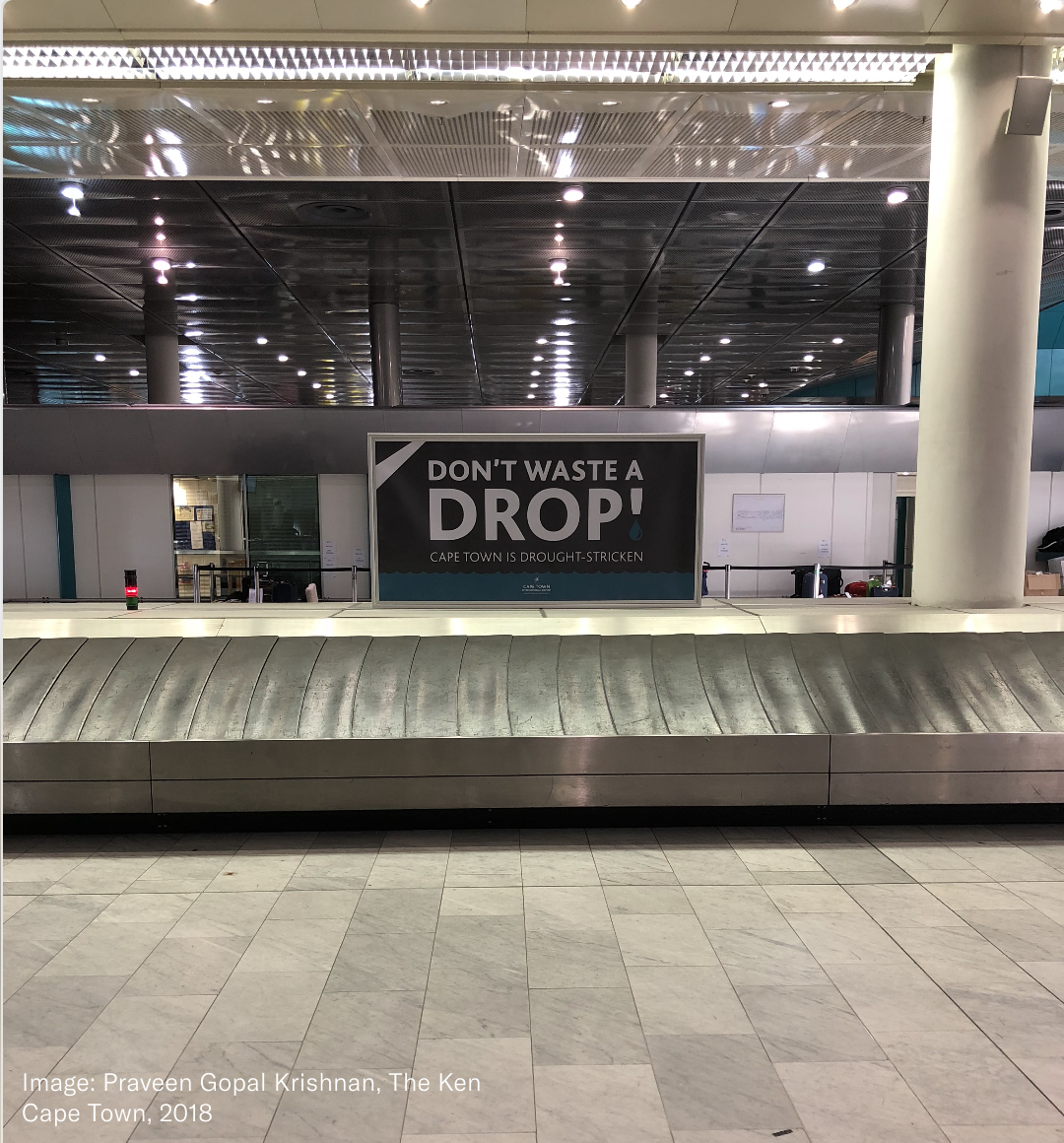

My flight has just landed in Cape Town, and I’m at the conveyor belt at the airport waiting for my bags.

It’s a late summer evening, the airport is empty. My bags are nowhere to be found and I’m getting impatient. I keep peering down the length of the belt to check if there’s any sign of it swinging into action. No luck.

A large sign stares back at me, equally impatiently.

It’s been a 15-hour journey from Bengaluru and I’m exhausted, and somewhat cranky. I don’t have an internet connection, so there’s nothing to distract myself with. I give up and head to the restroom. A few minutes won’t make a difference, I tell myself. My bags aren’t going anywhere.

There’s no running water in the bathroom tap. Mentally, I’m already composing a Linkedin post about how India is much better. Sure, we may have our problems, but at least our airport bathrooms work (mostly). Plus, we have UPI. Nothing screams development more than QR codes.

Then I notice the signs.

They are everywhere.

And that’s when I know this is no ordinary situation.

In early 2018, Cape Town almost ran out of water.

The city was facing a drought that it hadn’t experienced in almost four centuries. In January, which was when I landed in Cape Town and had that airport experience I just described, the government had just announced a countdown to “Day Zero”—the day when they would turn off the municipal water supply across the city and ask four million people to stand in queues everyday at certain specific taps to collect limited rations of water. Armed guards were expected to be called in to watch over the taps, and to stop fights and violence.

This crisis didn’t happen overnight. Cape Town’s water crisis had escalated over several months, and the city government tried several things to address it. They tried to procure water from other regions. They tried to build desalination plants quickly. They also implemented civic water restrictions slowly, over months, and assigned levels to it depending on the severity. In late 2016, they set it to Level 2—which restricted garden watering to thrice a week for a maximum of an hour a day. In June 2017, they raised it to Level 4—which limited water usage to 100 litres per person per day. By September, this had gone up to Level 5—which banned outdoor and non-essential use of water.

When I landed in Cape Town in January, the city had just escalated it to Level 6.

It was also the final level.

Level 7 was Day Zero.

Thanks to a combination of work and leisure, I’ve travelled to all kinds of places under various circumstances, but nothing comes close to the couple of weeks of dystopia I experienced that summer at Cape Town. On the surface, I found it was a lovely city, with amazing museums, a powerful history, and incredible food. I did what any tourist in Cape Town would do. I went up Table Mountain, lounged on the beach, cycled through the city, attended outdoor music festivals, and met some lovely penguins. But wherever I went, whatever I did, I was constantly reminded that water, something I took for granted, was just out of reach.

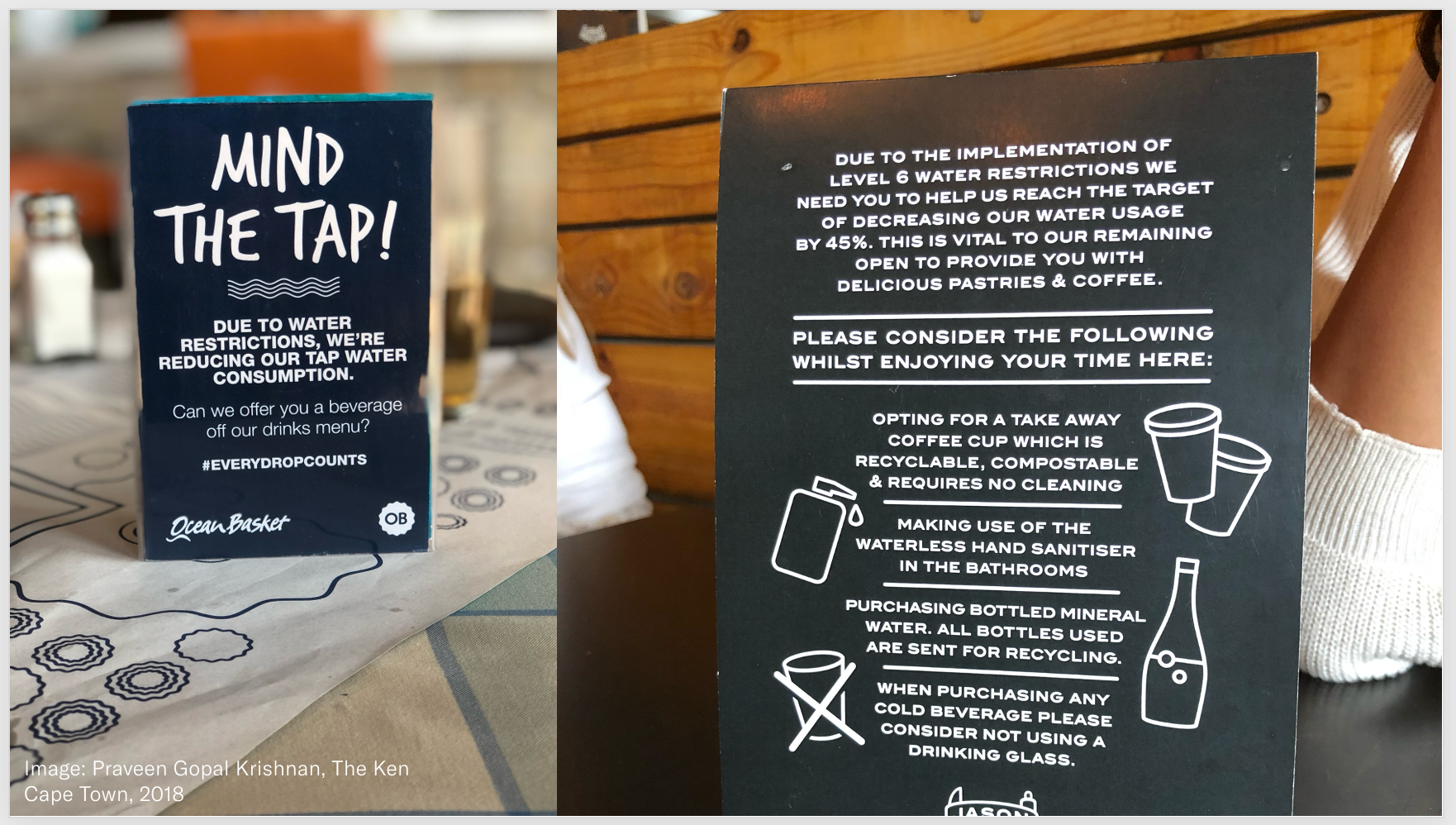

At bars, you could have all the beer you wanted, but nobody would serve you water.

At grocery stores, purchases of bottled water were tightly controlled.

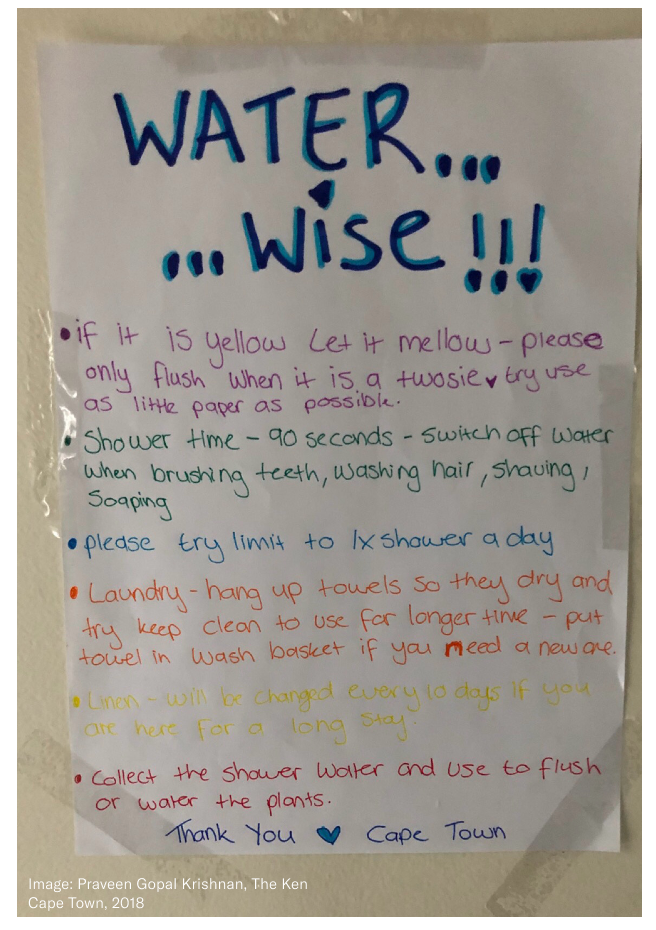

At my Airbnb, a notice pinned in the room informed me that flushing after using the toilets was discouraged (the city-wide tagline was “If it’s yellow, let it mellow”).

I also had to learn how to take 90-second showers—the maximum permitted by law. During my shower, I had to place a bucket in front of me, and the little water I collected was to be used for watering plants.

Cape Town’s Day Zero crisis was the first time that a horrified world got a glimpse of what happens when a major city comes perilously close to a full-on Mad Max Fury Road situation. This set off a flurry of activity and research. In March 2018, when Cape Townians were still taking 90-second showers, science publication Down to Earth did a study to figure out which cities across the world were most vulnerable to water scarcity. They identified 200 cities globally. Of these, they narrowed down 10 that were fast moving towards Day Zero. Some of these names aren’t surprising. Nairobi made it to the list. So did Kabul. Buenos Aires. Beijing.

One Indian city also made it to the top 10.

Bengaluru.

Just like in Cape Town, the water crisis in Bengaluru continues to worsen by the day. Borewells are drying up. Water supply all across the city has been disrupted, and the city’s already choked roads now have water tankers contributing to the traffic. Even high-rise apartment complexes aren’t immune from the crisis.

This water crisis is not unexpected. A lot of people saw this coming, a long time ago. For years, multiple agencies have been predicting that Bengaluru would soon witness acute, persistent, water shortages. The causes for the water shortages were also well-known—destruction of lakes, a reduction in groundwater, and disruptions in monsoons due to climate change.

Everyone knows this. They’ve also decided who is to blame for this state of affairs. Perhaps it’s the government, or climate change, or migrants. Also, depending on who you ask, the solution to the crisis involves actions such as taking control of water tankers, declaring mandatory WFH, or technology solutions like building apps that give real-time data.

And once again, this is the bigger problem.

Like I wrote during the floods, Bengaluru’s solutions are Bengaluru’s problems.

It’s dying of thirst because it’s drinking its own Kool-Aid.

And this becomes even more apparent if you look at what Bengaluru is doing in 2024, and contrast it with what Cape Town did in 2018.

There are significant parallels between Cape Town and Bengaluru. Both are cities that have grown far too quickly, mostly driven by migration. Just like Bengaluru, Cape Town’s administration was initially also criticised (probably justifiably) for apathy, incompetence, and a lack of planning of resources. Cape Town, even though it’s about a third in size, is also a city that looks like Bengaluru—income inequality is high, and geographically, the city has specific clusters separating the rich from the poor.

When the crisis hit in 2018, one of the first things that Cape Town did to get through it was pour massive investment into public education about the water crisis. That’s because the city quickly realised that the only way it could solve the crisis in the long-term was through managing demand, while it hunted for supply-side solutions. And the only way it could manage demand was if it co-opted the city. It did this through a combination of carrot and stick—including tariffs, incentives, and provision of free water services to the urban poor.

And the response from the city was immediate. Studies later demonstrated that while lower-income suburbs took their time initially to adjust to the water restrictions, “middle- and higher-income suburbs responded immediately”. Across the board, lower-, middle-, and higher-income suburbs reduced their water demand by anywhere between 30% to 60%.

Bengaluru’s approach is different. The city isn’t being co-opted.

If anything, it’s the opposite.

Amid the worsening water shortage in Bengaluru and the temperature inching towards 40 degrees Celsius, there has been a growing call for companies to switch to work from home and educational institutes to resume online classes to save water and reduce the burden on the employees and students.

Several citizens and citizen groups have taken to social media to ask Karnataka Chief Minister Siddaramaiah to make work from home mandatory for IT companies and to allow children to take online classes from home. If the strategy has worked during Covid, it'll work during the water crisis as well, they said.

Bengaluru water crisis: Residents push for work from home, online classes until monsoon, Moneycontrol

I understand the logic behind this. Less people in the city means more water for the rest. But the difference in the approach is interesting. It’s not just the people. On the administrative side, demand-side reductions aren’t even considered seriously as an option. Instead, they seem to be focused on the supply-side. Around a week back, Bengaluru’s administration announced that they’ll be seizing and taking control of all water tankers in the city. They also implemented some price caps. By the way, Bengaluru’s water tankers deserve a separate edition, but if you want to get a better idea of how it works, I highly recommend this incredible, investigative story written by one of our favourite journalists, Samanth Subramanian, back in 2017.

This is not to suggest that supply-side initiatives don’t work. Cape Town did some of them too. Ask any water expert anywhere in the world, and they’ll tell you that there’s one reliable “hack” that any city can implement on the supply-side that reduces water demand. Simply—it’s to reduce the pressure of water in the lines. Less pressure slows the flow of water in the taps, and everyone simply uses less water, with little change in behaviour. Reduction in pressure also has the benefit that it reduces water leakage, so overall, things get better for everybody. Cape Town implemented this religiously, and it played a significant role in water management. Several papers have been published that correlate water pressure management with demand reduction. It’s simple. It’s effective. And it works.

As far as I can tell, Bengaluru’s administration hasn't done this. Maybe they can’t.

But we know what can happen when they do.

Among various other woes, those living in residential areas of Bengaluru are grappling with the problem of illegal suction pumps attached to pipelines of the Bangalore Water Supply and Sewerage Board (BWSSB).

According to some residents, many houses and commercial establishments located on arterial roads use suction pumps to draw more water, which results in very little or no water reaching the remaining residents.

H.E. Chandrashekar, secretary of the Federation of HSR Layout Residents’ Welfare Association, also approached the BWSSB Chairman with a similar complaint. “As many people are installing suction pumps, residents living in high ridge areas are not getting any Cauvery water through BWSSB pipes,” he said.

He explained why many people are resorting to such illegal measures, “It is because there is no water pressure in the pipes. If BWSSB maintains the regular water pressure, then everyone, including those living in high ridge areas, will get adequate water.”

He also said that filling and supplying water from a tank built on the 31st main road in their locality, which has been empty for 20 years, could help the layout in such an hour of crisis.

A tenant, who lives in HSR Layout 6th phase, said, “There is no way to get Cauvery water if not for these suction pumps. Everyone in my area, including my landlord, uses suction pumps. We get Cauvery water only once a week. Due to decreased pressure, we will hardly get anything for our houses without suction pumps.”

Bengaluru Water Crisis: Illegal suction pumps rob water from law-abiding residents of Bengaluru, The Hindu

Another sharp distinction between Cape Town and Bengaluru is what we see in terms of positive and negative reinforcement. The response in Bengaluru to the water crisis appears to be driven by creating disincentives. Levying fines. Registering tankers. Taking permission. Fixing price caps. Taking action. The city even launched an app to report people who are using water illegally. It also launched another app where residents could “apply for a no-objection certificate” to dig borewells.

Do you know what Cape Town did?

This is one of my favourite stories.

It published a water map of the city.

On the map, it combined water-usage data with geographical information and colour-coded houses based on their water consumption.

And the most interesting part of the story is that it only acknowledged houses that were achieving the target.

Remember, the city knew which houses weren’t hitting the targets, but they created this map to acknowledge and recognise those that did—essentially a reward system.

As the Urban Sustainability Exchange noted in a case study, “the Water Map experienced some of the highest internet traffic ever experienced by a City of Cape Town webpage. It was widely reported on in the local media and received much attention on social media. The Water Map thus achieved substantial water conservation awareness and is believed to have contributed to the dramatic reductions in domestic water use which prevented the City from running out of water, the so-called “Day Zero”.”

I love this story because Cape Town found a way to drive behavioural change using technology. Bengaluru’s residents worship everyday at this altar, but in the context of things like 10-minute groceries, ride-sharing and deliveries—not for water conservation.

This dissonance of Bengaluru’s tech community and how they view technology is vastly understated. At one level, there’s a cultish belief that technology can not just disrupt anything, but that this disruption makes everything better for everybody. AI can solve the traffic problem. Blockchain can solve corruption. UPI can boost the economy. This is the story that they’ve told for decades—to themselves, to their employees, and to VCs. They’ve been telling this story for so long that they’ve started to believe it themselves. Even the city’s administrators have been using this narrative against the city—they have launched not one but four apps to address the water crisis. Four! Because as we all agree, apps are always the solution.

There’s a reason why this city has founders building apps to book tankers, but does not have any advocating for smart meters, which track and give real-time data about water usage all across the city—something that Cape Town relied on heavily to make decisions about what it needed to do next. The prevailing belief in Bengaluru is that apps that deliver things that make our lives easier is technology at work. Smart meters are not.

And at the end of the day, the overarching reasons why Bengaluru is different from Cape Town are apparent. The government believes that fines are better than rewards. The people who live in the city believe that withdrawal from the city, either by leaving it or by closing themselves off in gated communities, is better than the alternative. And finally, the cult of technology, and how it’s perceived as a solution, blind the city’s smartest people from advocating for things that actually work.

Bengaluru is dying of thirst because it’s drinking its own Kool-Aid.

Take care.

Regards,

Praveen Gopal Krishnan

https://sg-mktg.com/MTcxMDU2NTY3N3w4bGowbEFVM0s2UWtZRVZldlpRNWZwOUFLdHlBRTZxdk9mZnV3TTNzR2s1RDdieFZjcnVqcTlqZmo0Q29iX3dLalhXYkRIX2pyZVM3dEFYQzZTRm1SRlc5RVRHZ3JYdnF3TDNkZUJvdXF4dHpRc0NYYjI2R3VMcWh3RDNSOFdwazVrSnJBQlpOMlY3MVJyLWV1V3VNV05ieEpvUW9kSUhfVGJUZ3ZaUU0yd0FxTjk5a3drQ2NwM1VmeXJpUDNNcllWWHIxU1J1VnF2WGlmWFdnLWk3LVN3TDR0VFhyTVVzaldfZzlJT1k4cF9xYTZnUW10Rm5ZUjZwQW9sLUFxdmhTemc9PXxF4MjRayW3C-GMI5KGGOMHoReIbJgktRNzgoO3V2p28g==

The Nutgraf is a paid weekly emailer that explains fundamental shifts in business, technology and finance that happened over the last seven days in India. In a way you’ll never forget.

Know someone who would like The Nutgraf?

Want to receive The Nutgraf every week?

The Nutgraf is published by The Ken—a digital, subscription-driven publication focussing on technology, business, science and healthcare.

This newsletter is only available to the subscribers of The Ken.

Already a subscriber? Log in

The only business subscription you need

Unrivaled analysis and powerful stories about businesses from award-winning journalists.

Read by 5,00,000+ subscribers globally who want to be prepared for what comes next.

-

MOST POPULAR

App Access

iPad App Access

Priority Access

To new product offerings, features, community features, and events

2 Years

Archive access to the last two years of stories

2

Simultaneous browser sessions

+

1

Android/iOS App

App Access

iPad App Access

Priority Access

To new product offerings, features, community features, and events

Unlimited

Access to all The Ken's Archives

2

Simultaneous browser sessions

+

2

Android/iOS App + iPad App

App Access

iPad App Access

Priority Access

To new product offerings, features, community features, and events

Unlimited

Access to all The Ken's Archives

2 + 2

Simultaneous browser sessions

+

2 + 2

Android/iOS App + iPad App

Not Ready to Subscribe?

Sign up for free with just your email address and get one exclusive subscriber story, unlocked just for you. Every day, for 30 days. Sign up for free

Trusted by 5,00,000+ executives and leaders from the world’s most successful organisations and students at top post-graduate campuses

Sharp, Original, Insightful, Analytical, Handcrafted

Unrivaled analysis and powerful stories about businesses in India and abroad from award-winning journalists. Includes access to long-form articles, premium newsletters, and our top-ranked podcasts.

Coverage across Sectors, Companies, and Geographies

Decode the most significant shifts in business, technology, startups, and healthcare. All told through a combination of original reporting, beautifully visualised data, and compelling narratives.

Made even better by a 5,00,000+ community

Our subscribers include leaders from the world’s most successful companies, students at top post-graduate campuses, and smart, curious people who want to understand how business is shaping the future.

FAQs

We have three subscription plans - Basic, Premium, and Premium Duo.

- The Basic plan only gives you access to daily long-form stories, subscriber newsletters, free podcasts, and archive access for the previous two years. You won’t get our premium newsletters, premium podcasts, visual stories, and the iPad app.

- The Premium plan gives you complete access to all of The Ken’s products and features.

- The Premium Duo plan gives you complete access to The Ken for two independent accounts.

We publish sharp, original, deeply reported long-form stories from India’s startup ecosystem, internet economy, and publicly listed tech and consumer companies. Our stories are forward-looking, analytical, and directional—supported by data, visualisations, and infographics. We use language and narrative that is accessible to even lay readers. And we optimise for quality over quantity, every single time.

Our specialised subscriber-only newsletters are written by our expert, award-winning journalists and cover a range of topics across finance, retail, clean energy, and edtech, alongside weekend newsletters like The Nutgraf and First Principles.

Yes, you can upgrade to a higher plan while your current subscription is still active. Our system will automatically give you a discount against the remainder of your current subscription.

You will get a discount equivalent to the time remaining in your current subscription.

Yes, we do have corporate subscriptions, corporate gift subscriptions, and campus plans for larger groups that wish to read The Ken together. Write to us at [email protected] and we'll help you with that.

Yes. You will have to upload a valid student ID card during checkout to avail the 50% discount. You can purchase a student subscription here.

We do not allow downloading and distribution of our stories. The Ken is a digital subscription-based product and only those with an active subscription will have access to the stories, either on our app or the website.

We allow two simultaneous logins per subscription for the Basic plan, via only web and mobile.

We allow three simultaneous logins per subscription for the Premium and Premium Duo plans, via web, mobile, and Android tablet/iPad.

We do not offer any cancellations or refunds. If you are facing any issues with your subscription, you can write to us at [email protected].

Sorry, no. Our journalism is funded completely by our subscribers. We believe that quality journalism comes at a price, and readers trust and pay us so that we can remain independent.

Looking for Group Subscriptions?