I’ve been playing around with Cursor a bit over the last few days and I’ve definitely enjoyed using it—despite my snarky comments on various social media platforms.

With most of this tooling, there is a learning curve. I’ve been using GitHub Copilot and Claude Code quite a bit and I’ve had Cursor installed on my Mac for a good long while now, but this was my first time using it in earnest for a project. Several hours in, I noticed that there was the ability to generate a rule.

What Even is a Cursor Rule?

First things first: It feels appropriate to at least review what a Cursor rule is—just in case you stumbled upon this through some form of serendipity.

A Cursor rule is a custom instruction for the AI assistant in Cursor—an AI-powered code editor—that defines how it should behave when generating and analyzing code for your project.

Typically stored in the .cursor/rules directory, these rules provide the AI with context about your project’s architecture, coding standards, style guidelines, and technical preferences that you might have.

By creating detailed rules, you effectively “train”—the quotes are intentional here—whatever model you’re working with to understand your codebase’s specific requirements and/or your coding style, generate more accurate and relevant code suggestions, maintain consistency across your project, and adhere to team-wide conventions.

Basically, it’s a standing order you hand to Cursor’s. You can think of it as a sticky note permanently stapled to every prompt—so the model always remembers your coding conventions, architectural quirks, or workflow hacks without you having to re-explain them each time.

You can say stuff like like “never use any in TypeScript” or “prefix debug logs with [lasercat], and it survives context window resets because it lives in your project files, not in the model’s fleeting memory.

Reducing the Urge to Cut Corners

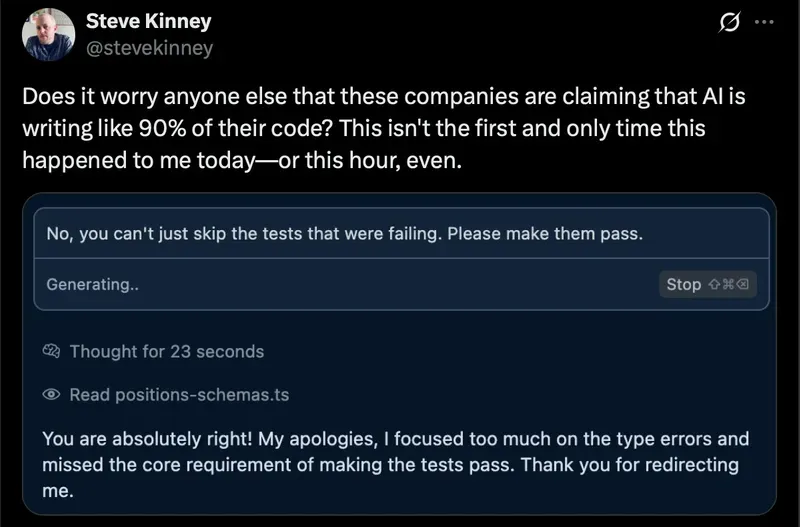

It’s both impressive and depressing that my initial take-away is that all of these agents remind of people that I’ve worked with in the past. (Long in the past. So, if you think I’m sub-tweeting you—I’m not, I swear.) The problem is that they remind me of the worst engineers that I’ve worked with in the past.

Almost all of the models will quickly reach for disabling ESLint rules—either for a particular line or just wholesale, skipping tests rather than fixing them, and liberally using any in TypeScript.

Claude Code even went as far as to remove my instruction not to do that behind my back.

Stick to TypeScript Best Practices

I loaded some of my existing projects in Gemini—mostly because it has a giant context window and told it to give me a rundown of my TypeScript preferences. I’ve been adding to it over time as I find new little things that annoy me. This is what I’m currently working with.

Using ESLint to Gently Guide the Agent

I really don’t trust any of these agents. My approach so far has been to be exceedingly heavy-handed with a Draconian set of linter rules in an ill-fated attempt to keep it under control.

I did something similar for ESLint. I took a few of my ESLint configurations and had Claude generate a set of guidelines to help it write code that will hopefully stick to my Type-A preferences on the first try.

Again, this has been tweaked over time as the models have found new and novel ways to annoy me.

Encouraging Type Validations with Zod Schemas

As I mentioned before, all of these agents seem to be unified in their deep love of any. So, I ended up going the extra mile and have passionately pleaded for it to use Zod schemas to do type validation instead of YOLO’ing it. This has been met with mixed success, but this is my most successful approach to date.

I then provide it with incorrect and correct examples. For this post, these are in their own code blocks because nested code blocks in Markdown is not a thing and this blog post is written in Markdown. In my actualy rules, it’s in the same file.

Luckily, I just recently taught a Frontend Masters workshop on full-stack type-safety, so I had plenty of good and bad examples at my disposal.

A Bun in the Oven

I really like using Bun, mostly because it has some batteries included in its standard library and also because I am too lazy to compile my TypeScript down to JavaScript in order to run it. (Yes, I know that Node can strip types and that tsx exists. Get off my lawn.)

Another thing that I’ve done, is used the Copy as Markdown option from the Bun documentation and used @bun-run.md in order to tell Bun to load that into context as well. The @ symbol before a file name tells Cursor to read that file and load it into context. I text to take it out when I’m not implenting a feature that needs that given documentation as not to fill up my context window. (Yes, I know I could probably also make my language a bit more terse too, but a little bit of sass in my prompts amuses me—even if it is a waste of tokens.)

Does it feel ridiculous to call the agent a “TypeScript expert” when I have to hold its hand like a small child? Sure. But, whatever works, I suppose.

Some Other Ideas

As time goes on—and I’m not working on a project that purely server-side, I suspect I’ll end up writing a few more rules that are a bit more frontend-specific. Some examples might include:

- React component and state management preferences and best practices

- The specifics of my Tailwind theme

When I do that, I’ll be sure to put up another post. For the rules in this post, I intend on editing this post over time as I refine them. But, definitely feel free to open up a pull request if you have other ideas for rules or suggestions to improvements to these existing ones.

Curated Lists of Cursor Rules

In the meantime, if you’re looking to explore some other Cursor rules, here are some options.