Political scientist Brian Schaffner writes:

If you’ve paid any attention at all to the news recently, you have probably seen more than a few stories about how the economy is weighing down President Biden’s reelection hopes. Many of these stories are based on data from polls that ask people about their own economic situations and also ask them what they think about Biden or how they plan to vote in 2024.

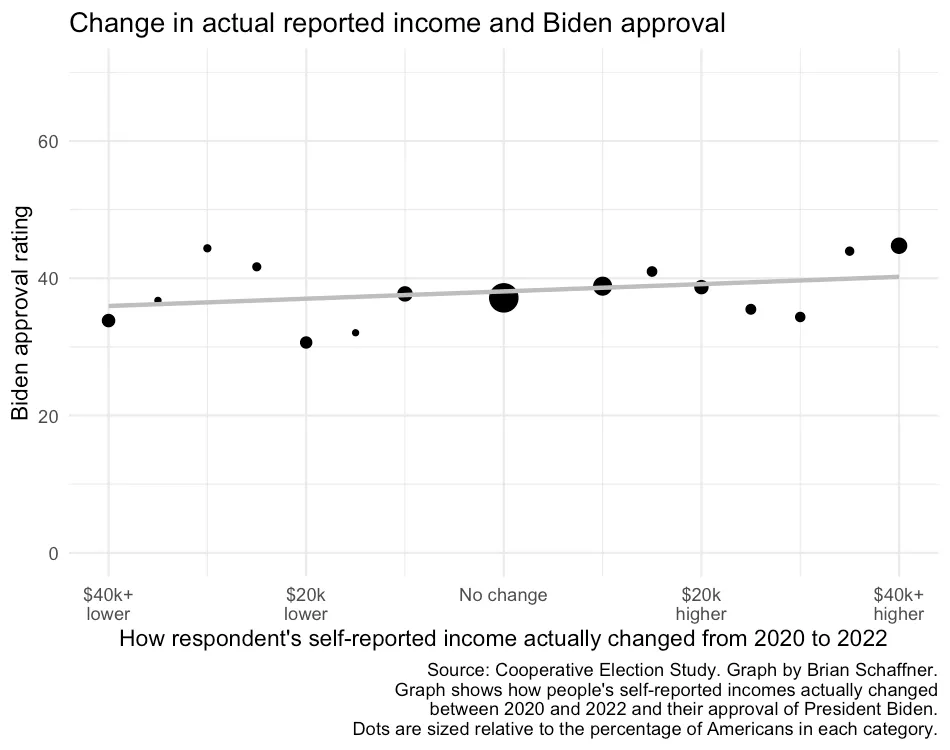

Such an analysis may look something like the following graph, which plots responses to a question we asked on the Cooperative Election Survey about how each person’s household income has changed over the past year and their approval rating of President Biden. . . .

But we also see a potential red flag when we look at this data: more Americans reported that their incomes decreased rather than increased over the past year despite the fact that government data indicates that wages and salaries are on the rise. . . .

Republicans were much more likely to report that their incomes declined during the previous year compared to Democrats. 35% of Republicans reported a decline in household income compared to 19% of Democrats.

Schaffner continues:

Is it really true that Republicans are struggling significantly more than Democrats when it comes to their household incomes? Or is this another example of a pattern that survey researchers call “expressive responding” — a phenomenon where individuals strategically provide dishonest answers to survey questions in an attempt to make their party look good or the other party look bad?

A Republican answering our survey might consider saying they are doing worse economically than is actually true as a way of supporting the narrative that the economy is struggling under the Biden presidency. Likewise, Democrats may report that they are doing better economically than they are to undermine that same narrative.

What can the data say? Here’s Schaffner:

It is often hard to detect survey respondents who are engaging in such expressive responding because we don’t actually know when someone is giving dishonest survey responses. (Though see here for work I did with Sam Luks where it was pretty clear). But in the case of income change on the 2022 CES, we actually do have data that allows us to get a good sense of this because it just so happens that 11,000 of our respondents were individuals we had previously interviewed back in 2020. Each time we interview a respondent, we ask them to report what their household income actually is. So for each respondent we know what they said their household income was in 2020 and what they said it was in 2022. Since these questions provide precise response categories and are buried among other demographic questions, it is unlikely that respondents would think to be dishonest when answering them in the same way that they might for the more vague and politically relevant question about income change.

So what do we see when we explore what people reported their income was in 2022 compared to what they reported it was in 2020?

In the 2022 survey, “17% of Americans reported that their income decreased somewhat in the past year while another 10% said that their income decreased a lot. Only 19% of Americans reported an increase in their income.”

But when comparing to the past survey: “only 18% of Americans gave a lower household income in 2022 than they did in 2020, while 35% reported a higher income level. Additionally, the partisan differences on this metric are much smaller — 21% of Republicans reported lower incomes in 2022 compared to 2020 while 18% of Democrats reported the same.”

Shaffner continues, “these two questions are not completely comparable since the self-reported change question asks about the past year but this second approach compares incomes reported over a two-year period. Nevertheless, it is doubtful that too many people will have suffered a decrease in income from 2021 to 2022 if their income had increased from 2020 to 2022.”

After comparing responses of Democrats and Republicans, Shaffner states:

The unfortunate effect of this pattern is to exacerbate the kind of relationship we saw in the first graph, making it look like income change is having a major effect on Biden’s approval rating when in fact it is just as likely that how somebody feels about Biden is affecting how they answer the question about income change. I [Shaffner] can show this most clearly by recreating the first plot, but this time using the measure of how each respondent’s self-reported income actually changed between 2020 and 2022 rather than how they said it had changed during the previous year. Using this approach, it turns out that the relationship between income change and Biden approval almost entirely disappears.

He concludes:

This is not to say that the economic picture is completely irrelevant to Biden’s relatively low approval rating or his reelection chances next year. It is reasonable to suspect that some swing voters are being persuaded by high inflation. But what this analysis shows is that simply asking people how inflation is affecting them and then comparing that to how they might vote in 2024 is not a good way to establish an accurate picture of that relationship. Ultimately, we cannot always take at face value what people tell us in polls to support a narrative that is circulating in the news.

Good point. I have nothing to add.

P.S. Schaffner and his colleagues also have a post on the claim that liberals are happier than conservatives, or the other way around. Regarding such statistics, let me point you to this post from a few years ago with further context here. It’s not just survey respondents who say things that aren’t true but fit their political ideologies.