Healthcare is picking up AI quickly, but the expectations around it sometimes feel out of sync with how these systems actually behave. There’s still an assumption that AI should act like traditional software: steady, predictable, and consistent. So, say someone asks, “If I run the same problem twice, will I get the same result?” That’s a question we hear all the time in early AI pilots. What they’re really asking for is confidence that the system won’t surprise them. But intelligence—human or artificial—doesn’t work that way.

Building AI That Improves Care in Healthcare

Doctors reviewing the same chart don’t always agree. Two clinicians can look at identical symptoms and still recommend different next steps. Even lab results show slight variation when run more than once. Beyond individual variation, the world around these systems shifts: workflows change, populations change, and the context an AI operates in today won’t look exactly the same tomorrow. AI systems, which operate probabilistically, reflect that same kind of variation. The goal isn’t to eliminate it. It’s to understand it, measure it, monitor it, and design an adaptable system that accounts for when things start to drift. In other words: acknowledging the friction and designing for it.

This shift is happening at the regulatory level, too. In 2025, the FDA formally asked for public feedback on how AI‑enabled medical devices should be measured in real‑world conditions [1]—a signal that evaluation and drift monitoring are no longer optional. That’s the gap this paper addresses. If healthcare leaders want AI they can trust, they need pilots that generate real evidence—not anecdotes, not one‑off demos, but reproducible results grounded in experiment design and UX research methods. But the transition from early experimentation to broader adoption has stalled largely because clear evaluation standards don’t yet exist.

This paper outlines practical methods and frameworks Atomic Object is already applying on real projects to help close that gap and make AI safer to adopt. Taken together, these ideas lay a roadmap for how organizations can move from a promising prototype to something dependable enough for clinical and operational use. In the best‑case scenarios, this approach can even reduce some of the natural human variability we see across clinical settings—creating more trust in the systems meant to support care.

The Core Problem: Why Healthcare AI Pilots Break Down

Many healthcare AI pilots fall apart long before they reach real adoption—not because the ideas are bad, but because the way they’re tested and evaluated just isn’t enough. MIT found that 95% of GenAI pilots fail [2], often because teams focus on the wrong metrics or rely too much on feel‑good “time saved” stories. And some of the issues don’t show up until an AI system leaves the test environment and hits the messiness of the real world:

Data that doesn’t match what the model was trained on.

Models might look great in testing, but once they hit real‑world data—messier, inconsistent, and full of surprises—they can stumble. It’s one of the quickest ways drift shows up.

Unusable or inconsistent data structures.

As The Economist highlights, many teams discover too late that their data isn’t in a format an AI system can actually work with, making it difficult to produce reliable outputs [3].

Privacy and regulatory hurdles.

Strict rules around medical data—and the slow, complex process of validating AI systems—make it difficult to iterate, test, and refine models in real clinical settings.

The “black box” problem.

Clinicians hesitate to trust systems when they can’t easily explain or validate how an AI reached a decision. This is increasingly a compliance risk, as new transparency rules like the ONC’s HTI-1 require developers to provide clear explanations of the logic behind predictive decision support [11].

Starting with an AI idea instead of a real problem.

When teams jump to a solution too quickly, it often leads to misalignment—and the end product doesn’t actually solve anything meaningful for users.

Drift sits at the center of many of these issues: an AI system might perform beautifully in testing, then begin to fail when it encounters new inputs, new workflows, or new populations. Drift is not a failure—it is an expected property of AI systems operating in dynamic environments.

Model drift refers to the gradual decline in a model’s performance as the real‑world data it encounters changes over time. Even a well‑trained model can start producing inconsistent or incorrect results when the patterns, inputs, or relationships it learned from no longer match what it sees in practice. Drift is normal and expected—but without monitoring, it can quietly undermine decision‑making and trust in the system [5].

Without monitoring and regular evaluation, failures can go unnoticed until trust erodes and the pilot loses momentum fast.

The Taxonomy of Change: Categorizing Drift by Origin

To manage AI effectively, we must move beyond treating “drift” as a simple technical failure. For a healthcare executive, the goal is to identify where the change originates so they can hold the right team accountable for the fix.

1. Data & Pipeline Drift: When the “Fuel” Changes

AI is fueled by data. If the plumbing of your hospital changes—due to an EHR update, a new lab vendor, or a change in how nurses document symptoms—the AI receives “low-quality fuel.” This is often a silent failure that occurs before the AI even makes a decision.

- System & Input Shifts: Changes in software versions (like an Epic or Cerner update) or new hardware (like a different brand of heart rate monitor) that change how data is formatted.

- Source Mismatch: When a model built on “perfect” research data is suddenly plugged into the “messy” reality of a busy emergency department.

2. World & Clinical Reality Drift: When “Truth” Changes

Sometimes the data is fine, but the medical world has moved on. If your AI was trained to detect a disease using 2022 guidelines, it might provide “incorrect” advice in 2025 because medical standards have evolved.

- Evolution of Care: A shift in “the way we do things,” such as new CDC guidelines, new drug arrivals, or even a new strain of a virus that changes how patients present in the clinic.

3. Human & Workflow Drift: When “Behavior” Changes

This is often the most overlooked risk. It occurs when staff adapt their behavior in response to the AI. If the tool is frustrating or slow, clinicians will find “workarounds” that break the system’s logic.

- The Workaround Effect: When clinicians stop using certain features or start entering data differently to save time, effectively “tricking” the AI.

- The Echo Chamber: When the AI’s suggestions start to influence the staff so much that they stop thinking critically, creating a loop where the AI is essentially “grading its own papers.”

4. Outcome-Level Drift: When the “Bottom Line” Changes

This is the “check engine light” of the AI system. It tells you the system is failing, but not why. By the time this drift is visible, you are already losing ROI or risking patient safety.

- Performance Decay: A measurable drop in the system’s accuracy or an increase in “false alarms” that leads to clinician burnout and loss of trust.

Governance & Accountability Matrix

Effective AI management requires a cross-functional approach. While executive leadership owns the risk, the delivery team (Engineers and Designers) provides the instrumentation and agility needed to manage it.

| Category | The Business Risk | Primary Owner | Delivery Team Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data & Pipeline | Broken “plumbing” leads to garbage-in, garbage-out. | IT / Data Engineering | Software Engineers build resilient pipelines that “fail-safe” when data changes. |

| World & Clinical | Outdated medical logic leads to clinical irrelevance. | CMO / Clinical Leads | Developers build “swap-ability” so models can be updated without breaking the app. |

| Human & Workflow | Poor adoption and “workarounds” erode trust and ROI. | Operations | UX Designers observe clinicians to ensure the AI solves more problems than it creates. |

| Outcome Drift | Unexpected failures create liability and financial loss. | Executive Leadership | The Full Team instruments the system to provide “Check Engine” alerts to leadership. |

The Solution: Designing AI Pilots Like Regulated Experiments

At this point, one thing should be clear: success with healthcare AI is less about choosing the “right” model and more about adopting the right process. This is an emerging and fast-moving problem space. As models, tools, and regulations evolve, teams that succeed are the ones who treat AI projects as learning systems—designed to generate evidence, surface risk early, and adapt as reality changes.

“Success with healthcare AI is less about choosing the ‘right’ model and more about adopting the right process.”

At Atomic Object, we approach AI work the same way regulators increasingly expect it to be managed: as a lifecycle, not a launch. This aligns with the FDA’s shift toward a Total Product Life Cycle (TPLC) approach, where safety and effectiveness are managed through continuous monitoring and predetermined change protocols [9]. Pilots are not disposable proofs of concept; they are structured experiments that produce governance-ready evidence.

Scope note: This post is about evidence and operational risk—how you prove performance, detect drift, and decide when to expand deployment. It is not a guide to determining whether a feature is SaMD or non-device CDS; treat that as a separate, earlier scoping decision.

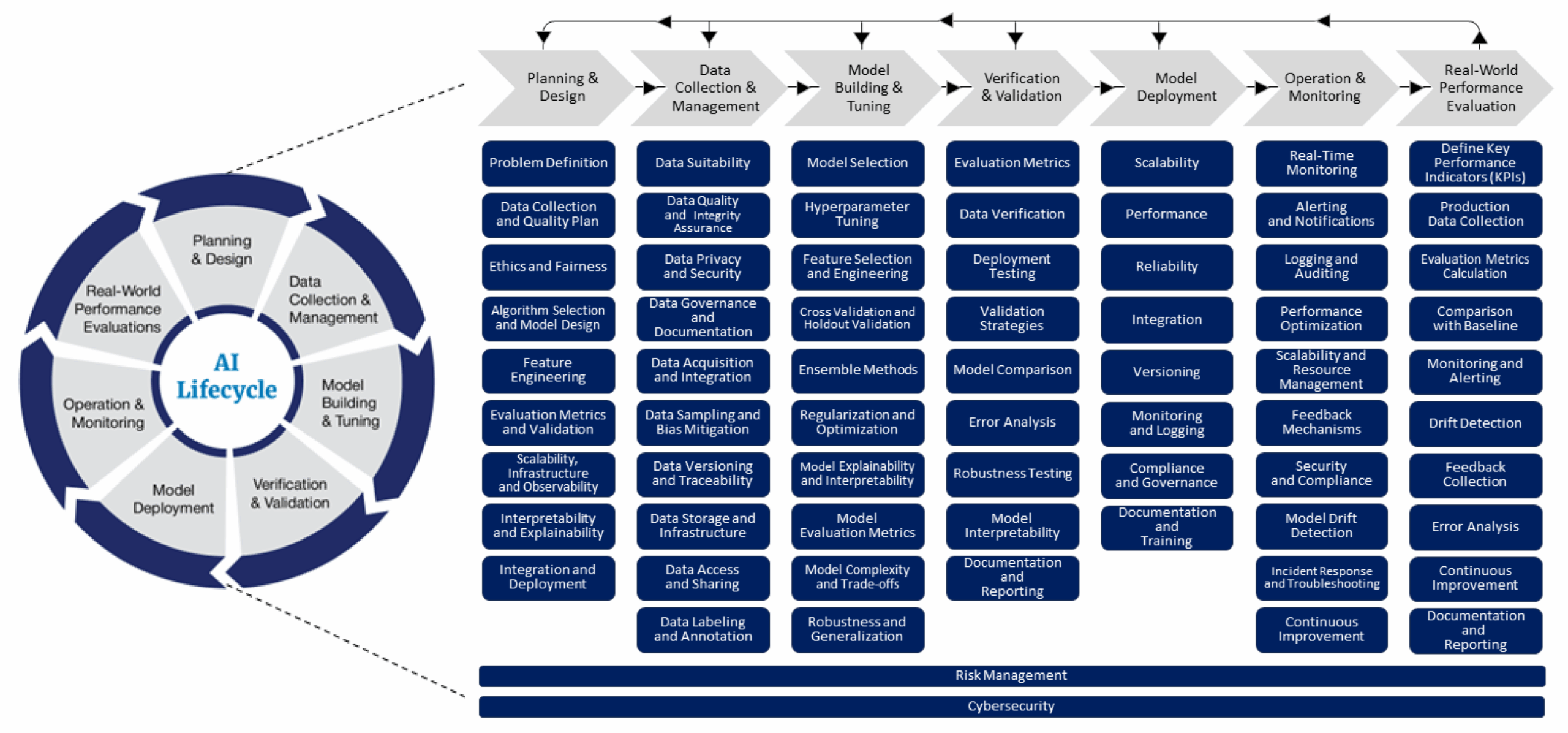

A Lifecycle-Driven Process for AI Projects

Each phase of the lifecycle answers a different governance question, but the connective tissue across all of them is design. Not visual design, and not interface polish—but experiment design, service design, and systems design: the practice of anticipating how systems behave over time, how people actually use them under pressure, and how those interactions shape risk, performance, and trust.

Figure 1: The FDA’s lifecycle management approach toward delivering safe and effective AI-enabled health care. Source: FDA Digital Health Center of Excellence.

A Design‑Led, Experiment‑Driven AI Process

We approach AI projects as a series of structured experiments embedded within real services. Each phase is deliberately designed to answer specific questions about behavior, risk, and readiness—before automation increases.

Experiment Design as the Backbone

AI development begins with the scientific method, not model selection. Teams pre‑declare hypotheses, success criteria, failure thresholds, and stop conditions before exposure to real users. Evaluation datasets, cohorts, and time windows are chosen deliberately so outcomes are reproducible, comparable, and defensible—not anecdotal.

UX & Service Design as Risk Anticipation

UX research is how teams surface risk early. By studying real workflows, edge cases, and decision‑making under pressure, designers identify where AI inputs and outputs may be misunderstood, ignored, over‑trusted, or repurposed.

Progressive Exposure via an Exposure Ladder

Rather than jumping straight to high-impact deployment, pilots move through a deliberate progression of system impact—offline evaluation → shadow mode → supervised deployment → constrained automation. Each transition is gated by evidence, not optimism.

- Shadow mode: Predictions are logged and evaluated against real-world actions, allowing teams to measure accuracy, error patterns, drift, and UX behavior in production conditions—without introducing risk.

- Clinician-in-the-loop (Supervised Deployment): The AI provides recommendations to clinicians who act as the final decision-makers. This phase surfaces trust calibration issues and workflow friction under real operational pressure.

- Constrained automation: The AI is allowed to take limited, well-scoped actions within predefined guardrails. Some clinical workflows should never cross this line; for many medical tasks, the goal is never to let the AI act alone. The ‘top of the ladder’ for a doctor’s tool is often just being a really good assistant that never leaves the doctor’s side.

Monitoring Behavior, Not Just Models

From day one, systems are instrumented to observe change across the full service: input mix, output distribution, subgroup performance, and human interaction patterns.

Human‑in‑the‑Loop as a Designed System

Human oversight is intentionally designed, not bolted on. Review workflows capture structured feedback, annotated errors, and escalation signals that feed quality assurance and learning.

Evidence as the Primary Output

The outcome of a pilot is not a demo—it’s evidence. One‑page reports summarize acceptance criteria, results (with uncertainty), error taxonomies, and a clear decision narrative: continue, revise, or stop.

ROI in healthcare AI is less about time saved and more about decision confidence. While early hype focused on immediate efficiency, industry experience suggests that the “real” ROI is often slower to materialize and rooted in clinical durability and clinician well-being rather than immediate administrative cost-cutting [10].

In Practice

In practice, this work comes together as a repeatable system for designing, governing, and improving AI over time. The techniques below are applied together, not in isolation:

- Treat evaluation datasets as long‑lived assets. Curate and maintain evaluation datasets as internal IP, used to compare models, run bake‑offs, and define clear swap criteria.

- Use a progressive exposure ladder. Move deliberately from offline evaluation to shadow mode, supervised deployment, and constrained automated use (when appropriate), with explicit promotion gates.

- Design human‑in‑the‑loop review from day one. Build structured feedback, annotated error review, and escalation paths into the system early to surface failure modes.

- Monitor the full service, not just the model. Instrument input mix, output distribution, and human interaction patterns using tools like those provided by the FDA’s OSEL [12].

Health AI: From Pilot to Proof

Healthcare AI does not fail because it changes—it fails when teams assume it won’t. Moving from pilot to proof requires treating AI systems less like traditional software and more like living participants in complex clinical and operational environments.

By combining rigorous evaluation methods with UX research, human‑in‑the‑loop design, and real‑world monitoring, organizations can generate the kind of evidence regulators, clinicians, and leaders are increasingly asking for. The goal is not perfect consistency, but understood variability—systems whose behavior is observable, explainable, and responsive to change.

References

- “FDA Seeks Feedback on Measuring AI‑Enabled Medical Device Performance.” American Hospital Association, 2025. https://www.aha.org/news/headline/2025-09-30-fda-seeks-feedback-measuring-ai-enabled-medical-device-performance

- Snyder, Jason. “MIT Finds 95% of GenAI Pilots Fail Because Companies Avoid Friction.” Forbes, 2025. https://www.forbes.com/sites/jasonsnyder/2025/08/26/mit-finds-95-of-genai-pilots-fail-because-companies-avoid-friction/

- “The Potential and the Pitfalls of Medical AI.” The Economist, 2020. https://www.economist.com/technology-quarterly/2020/06/11/the-potential-and-the-pitfalls-of-medical-ai

- Panch et al. “The ‘Inconvenient Truth’ About AI in Healthcare.” npj Digital Medicine, 2021. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41746-021-00463-1

- “What Is Model Drift?” IBM Think, IBM. https://www.ibm.com/think/topics/model-drift

- “Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning in Software as a Medical Device.” FDA. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health-center-excellence/artificial-intelligence-and-machine-learning-software-medical-device

- “Model Monitoring with Vertex AI.” Google Cloud. https://colab.research.google.com/github/GoogleCloudPlatform/vertex-ai-samples/blob/main/notebooks/official/model_monitoring/model_monitoring.ipynb

- “FDA Issues Comprehensive Draft Guidance for Developers of AI-Enabled Medical Devices (PCCP).” FDA, 2025. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-issues-comprehensive-draft-guidance-developers-artificial-intelligence-enabled-medical-devices

- “A Lifecycle Management Approach toward Delivering Safe, Effective AI-enabled Health Care.” FDA Digital Health Center, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/digital-health-center-excellence/blog-lifecycle-management-approach-toward-delivering-safe-effective-ai-enabled-health-care

- “Healthcare AI’s Elusive ROI.” Forbes / Becker’s Hospital Review, 2025. https://www.forbes.com/sites/spencerdorn/2024/10/10/healthcare-ais-elusive-roi/

- “Health Data, Technology, and Interoperability (HTI-1) Transparency Requirements.” ONC / HealthIT.gov, 2025. https://www.healthit.gov/topic/laws-regulation-and-policy/health-data-technology-and-interoperability-certification-program

- “Methods and Tools for Effective Postmarket Monitoring of AI-Enabled Medical Devices.” FDA OSEL. https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/medical-device-regulatory-science-research-programs-conducted-osel/methods-and-tools-effective-postmarket-monitoring-artificial-intelligence-ai-enabled-medical-devices