[This is an entry to the 2019 Adversarial Collaboration Contest by Nick D and Rob S.]

I.

Nick Bostrom defines existential risks (or X-risks) as “[risks] where an adverse outcome would either annihilate Earth-originating intelligent life or permanently and drastically curtail its potential.” Essentially this boils down to events where a bad outcome lies somewhere in the range of ‘destruction of civilization’ to ‘extermination of life on Earth’. Given that this has not already happened to us, we are left in the position of making predictions with very little directly applicable historical data, and as such it is a struggle to generate and defend precise figures for probabilities and magnitudes of different outcomes in these scenarios. Bostrom’s introduction to existential risk provides more insight into this problem than there is space for here.

There are two problems that arise with any discussion of X-risk mitigation. Is this worth doing? And how do you generate the political will necessary to handle the issue? Due to scope constraints this collaboration will not engage with either question, but will simply assume that the reader sees value in the continuation of the human species and civilization. The collaborators see X-risk mitigation as a “Molochian” problem, as we blindly stumble into these risks in the process of maturing our civilisation, or perhaps a twist on the tragedy of the commons. Everyone agrees that we should try to avoid extinction, but nobody wants to pay an outsized cost to prevent it. Coordination problems have been solved throughout history, and the collaborators assume that as the public becomes more educated on the subject, more pressure will be put on world governments to solve the issue.

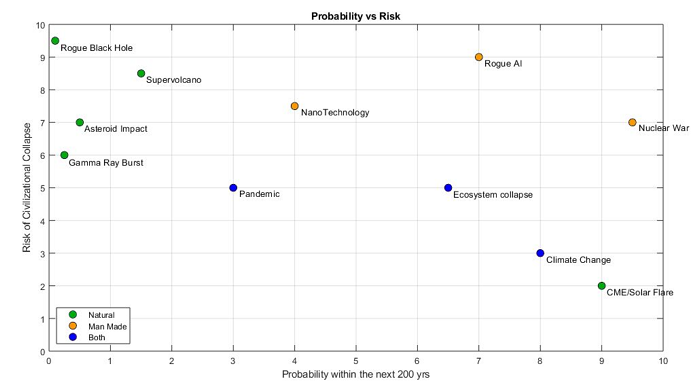

Exactly which scenarios should be described as X-risks is impossible to pin down, but on the chart above, the closer you get to the top right, the more significant the concern. Considering there is no reliable data on the probability of a civilization collapsing pandemic or many other of these scenarios, the true risk of any scenario is impossible to determine. So any of the above scenarios should be considered dangerous, but for some of them, we have already enacted preparations and mitigation strategies. World governments are already preparing for X-risks such as nuclear war, or pandemics by leveraging conventional mitigation strategies like nuclear disarmament and WHO funding. When applicable, these strategies should be pursued in parallel with the strategies discussed in this paper. However, for something like a gamma ray burst or grey goo scenario, there is very little that can be done to prevent civilizational collapse. In these cases, the only effective remedy is the development of closed systems. Lifeboats. Places for the last vestiges of humanity to hide and survive and wait for the catastrophe to burn itself out. There is no guarantee that any particular lifeboat would survive. But a dozen colonies scattered across every continent or every world would allow humanity to rise from the ashes of civilization.

Both authors of this adversarial collaboration agree that the human species is worth preserving, and that closed systems represent the best compromise between cost, feasibility, and effectiveness. We disagree, however, on if the lifeboats should be terrestrial, or off world. We’re going to go into more detail on the benefits and challenges of each, but in brief the argument boils down to whether we should aim more conservatively by developing the systems terrestrially, or ‘shoot for the stars’ and build an offworld base and reap the secondary benefits

II.

For the X-risks listed above, there are measures that could be taken to reduce the risk of them occurring, or to mitigate against the negative outcomes. The most concrete steps that have been taken so far that mitigate against X-risks would be the creation of organisations like the UN, intended to disincentivize warmongering behaviour and reward cooperation. Similarly the World Health Organisation and acts like the Kyoto Protocol serve to reduce the chances of catastrophic disease outbreak and climate change respectively. MIRI works to reduce the risk of rogue AI coming into being, while space missions like the Sentinel telescope from the B612 Foundation seek to spot incoming asteroids from space.

While mitigation attempts are to be lauded, and expanded upon, our planet, global ecosystem, and biosphere are still the single point of failure for our human civilization. Creating separate reserves of human civilization, in the form of offworld colonies or closed systems on Earth, would be the most effective approach to mitigating against the worst outcomes of X-risk.

The scenario for these backups would go something like this: despite the best efforts to reduce the chance of any given catastrophe it occurs, and efforts made to protect/preserve civilization at large fail. Thankfully, our closed system or space colony has been specifically hardened to survive against the worst we can imagine, and a few thousand humans survive in their little self-sufficient bubble with the hope of retaining existing knowledge and technology until the point where they have grown enough to resume the advancement of human civilization, and the species/civilization loss event has been averted.

Some partial analogues come to mind when thinking of closed systems and colonies; the colonisation of the New World, Antarctic exploration and scientific bases, the Biosphere 2 experiment, the International Space Station, and nuclear submarines. These do not all exactly match the criteria of a closed system lifeboat, but lessons can be learned.

One of the challenges of X-risk mitigation is developing useful cost/benefit analyses for various schemes that might protect against catastrophic events. Given the uncertainty inherent in the outcomes and probabilities of these events, it can be very difficult to pin down the ‘benefit’ side of the equation; if you invest $5B in an asteroid mitigation scheme, are you rescuing humanity in 1% of counterfactuals or are you just softening the blow in 0.001% of them? If those fronting the costs can’t be convinced that they’re purchasing real value in terms of the future then it’s going to be awfully hard to convince them to spend that money. Additionally, the ‘cost’ side of the equation is not necessarily simple either, as many of the available solutions are unprecedented in scale or scope (and take the form of large infrastructure projects famous for cost-overruns). The crux of our disagreement ended up resting on the question of cost/benefit for terrestrial and offworld lifeboats, and the possibility of raising the funds and successfully establishing these lifeboats.

III.

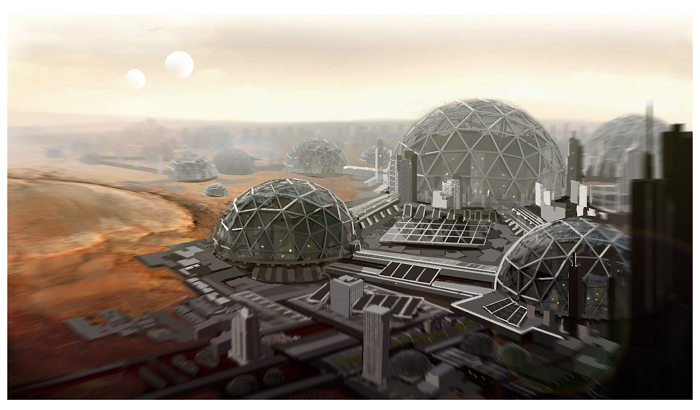

The two types of closed systems under consideration are offworld colonies, or planetary closed systems. An offworld colony would likely be based on some local celestial body, perhaps Mars, or one of Jupiter’s moons. For an offworld colony, the X-risk mitigation wouldn’t be the only point in its favor. A colony would also be able to provide secondary and tertiary benefits in acting as a research base and exploration hub, and possibly taking advantage of otheropportunities offered by off-planet environments.

In terms of X-risk mitigation, these colonies would work much the same as the planetary lifeboats, where isolation from the main population provides protection from most disasters. The advantage would lie in the extreme isolation offered by leaving the Earth. While a planetary lifeboat might allow a small population to survive a pandemic, a nuclear/volcanic winter, or catastrophic climate change, other threats such as an asteroid strike or nuclear strikes themselves would retain the ability to wipe out human civilization in the worst case.

Offworld colonies would provide near complete protection from asteroid strikes and threats local to the Earth such as pandemics, climate catastrophe, or geological events, as well as being out of range of existing nuclear weaponry. Climate change wouldn’t realistically be an issue on Mars, the Moon, or anywhere else in space, pandemics would be unable to spread from Earth, and the colonies would probably be low priority targets come the breakout of nuclear war. While eradicating human civilisation would require enough asteroid strikes to hit every colony, astronomically reducing the odds.

Historically, the only successful drivers for human space presence have been political, the Space Race being the obvious example. I would attribute this to a combination of two factors; human presence in space doesn’t increase the value of scientific research possible enough to offset the costs of supporting them there, and no economically attractive proposals exist for human space presence. As such, the chances of an off-planet colony being founded as a research base or economic enterprise are low in the near future. This leaves them in a similar position to planetary lifeboats, which also fail to provide an economic incentive or research prospects beyond studying the colony itself. To me this suggests that the point of argument between the two possibilities lies on the trade-off between the costs of establishing a colony on or off planet, and the risk mitigation they would respectively provide.

The value of human space presence for research purposes is only likely to decrease as automation and robotics improve, while for economic purposes, as access to space becomes cheaper, it may be possible to come up with some profitable activity for people off-planet. The most likely options for this would involve some kind of tourism, or if the colony was orbital, zero-g manufacturing of advanced materials, while an unexpectedly attractive proposal would be to offer retirement homes off planet for the ultra wealthy (to reduce the strain of gravity on their bodies in an already carefully controlled environment). It seems unlikely that any of these activities would be sufficiently profitable to justify an entire colony, but they could at least serve to offset some of the costs.

Perhaps the closest historical analogue to these systems would be the colonisation of the New World, the length of the trip was comparable (two months for the Mayflower, at least six to reach Mars), and isolation from home further compounded by the expense and lead time on mounting additional missions. Explorers traveling to the New World disappeared without warning multiple times, presumably due to the difficulty of sending for external help when unexpected problems were encountered. Difficulties associated with these kinds of unknown unknowns were encountered during the Biosphere projects as well, it transpired that trees grown in enclosed spaces won’t develop enough structural integrity to hold their own weight, as it is the stresses due to wind that cause them to develop this strength. It appears that this was not something that was even on the radar before the project happened, while several other unforeseen issues also had to be solved, the running theme was that in the event of an emergency supplies and assistance could come from outside to solve the problem. A space-based colony would have to solve problems of this kind with only what would be immediately to hand. With modern technology, assistance in the form of information would be available (see Gene Kranz and Ground Control’s rescue of Apollo 13), but lead times on space missions mean that even emergency flights to the ISS, for which travel time could be as little as ten minutes, aren’t really feasible. As such off-planet lifeboats would be expected to suffer more from unexpected problems than terrestrial lifeboats, and be more likely to fail before there was even any need for them.

The other big disadvantage of a space colony is the massively increased cost of construction, Elon Musk’s going estimate for a ‘self sustaining civilization’ on Mars is $100B – $10T, assuming that SpaceX’s plans for reducing the cost of transport to Mars work out as planned. In order to offer an apples to apples comparison with the terrestrial lifeboat considered later in this collaboration, if Musk’s estimate for a population of one million for a self-sustaining city is scaled down to the 4000 families considered below (a population of 16000) our cost estimate comes down to $1.6B – $160B. Bearing in mind that this is just for transport of the requisite mass to Mars, we would expect development and construction costs to be higher. With sufficient political will, these kinds of costs can be met; the Apollo program cost an estimated $150B in today’s money (why the cost of space travel for private and government run enterprises has changed so much across sixty years is an exercise left to the reader). Realistically though, it seems unlikely that any political crisis will occur to which the solution seems to be a second space race of a similar magnitude. This leaves the colonization project in the difficult position of trying to discern the best way to fund itself. Can enough international coordination be achieved to fund a colonization effort in a manner similar to the LHC or the ISS (but an order of magnitude larger)? Will the ongoing but very quiet space race between China, what’s left of Western space agencies human spaceflight efforts, and US private enterprise escalate into a colony race? Or will Musk’s current hope of ‘build it and they will come’ result in access to Mars spurring massive private investment into Martian infrastructure projects?

IV

Planetary closed systems would be exclusively focused on allowing us to survive a catastrophic scenario (read: “zombie apocalypse”). Isolated using geography and technology, Earth based closed systems would still have many similarities to an offworld colony. Each lifeboat would need to make its own food, water, energy, and air. People would be able to leave during emergencies like a fire, O2 failure or heart attack, but the community would generally be closed off from the outside world. Once the technology has been developed, there is no reason other countries couldn’t replicate the project. In fact, it should be encouraged. Multiple communities located in different regions of the world would actually have three big benefits. Diversity, redundancy, and sovereignty. Allowing individual countries to make their own decisions allows different designs with no common points of failure and if one of the sites does fail, there are other communities that will still survive. Site locations should be chosen based on

● Political stability of the host nation

● System implementation plan

● Degree of exposure to natural disasters

● Geographic location

● Cultural Diversity

There is no reason a major nation couldn’t develop a lifeboat on their own, but considering the benefits of diversity, smaller nations should be encouraged to develop their own projects through UN funding and support. A UN committee made up of culturally diverse nations could be charged with examining grant proposals using the above criteria. In practice, this would mean a country would go before the committee and apply for a grant to help build their lifeboat.

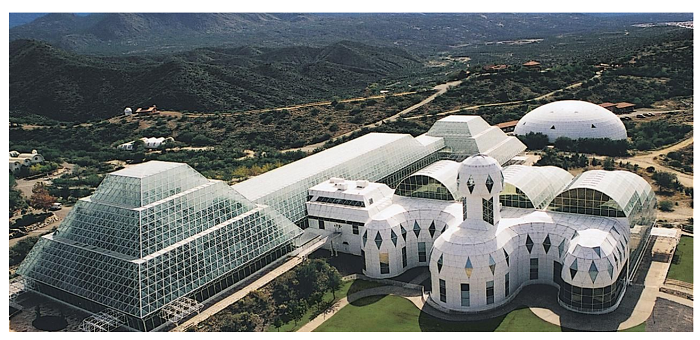

Let’s say the US has selected Oracle, Arizona as a possible site for an above ground closed system. The proposal points out the cool, dry air minimizes decomposition, located far from major cities or nuclear targets, and protected and partially funded by the United States. The committee reviews the request and their only concern is the periodic earthquakes in the region. To improve the quality of their bid, The United States adds a guarantee that the town’s demographics would be reflected in the system by committing to a 40% Latino system. The committee considers the cultural benefits of the site, and approves the funding.

Oracle, Arizona wasn’t a random example, In fact it’s already the site of the world’s largest Closed Ecological System [CES] It actually was used as the site of Biosphere 2. As described by acting CEO Steve Bannon:

Biosphere 2 was designed as an environmental lab that replicated […] all the different ecosystems of the earth… It has been referred to in the past as a planet in a bottle.. It does not directly replicate earth [but] it’s the closest thing we’ve ever come to having all the major biomes, all the major ecosystems, plant species, animals etc. Really trying to make an analogue for the planet Earth.

I feel like I need to take a moment to point out that that was not a typo, and the quote above is provided by that Steve Bannon. I don’t know what else to say about that other than to acknowledge how weird it is (very).

As our friend Steve “Darth Vader” Bannon points out, what made Biosphere 2 unique, is that it was a Closed Ecological System where 8 scientists were sealed into an area of around 3 acres for a period of 2 years (Sept 26, 1991 – Sept. 27, 1993). There are many significant differences from the Biosphere 2 project and a lifeboat for humanity. Biosphere 2 contained a rainforest, for example. But the project was the longest a group of humans have ever been cut off from earth (“Biosphere 1”). Our best view into what issues future citizens of Mars may face is through the glass wall of a giant greenhouse in Arizona.

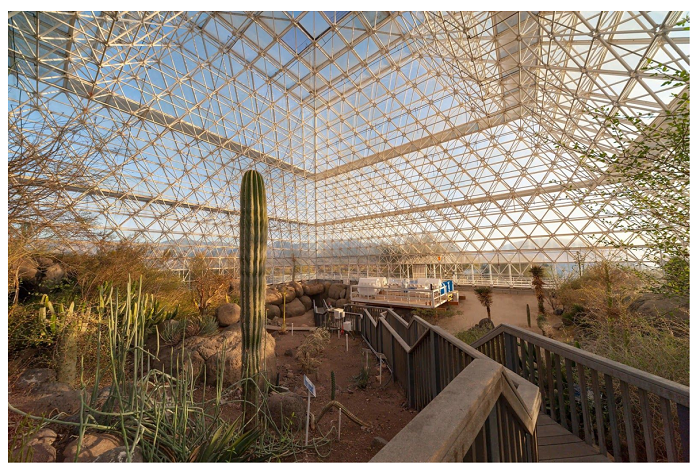

One of the major benefits of using terrestrial lifeboats as opposed to planetary colonies is that if (when) something goes wrong, nobody dies. There is no speed of light delay for problem solving, outside staff are available to provide emergency support, and in the event of a fire or gas leak, everyone can be evacuated. In Biosphere 2, something went wrong. Over the course of 16 months the oxygen in the Biosphere dropped from 20.9% from 14.5%. At the lowest levels, scientists were reporting trouble climbing stairs and inability to perform basic arithmetic. Outside support staff had liquid oxygen transported to the biosphere and pumped in.

A 1993 New York Times article “Too Rich a Soil: Scientists find Flaw That Undid The Biosphere” reports:

A mysterious decline in oxygen during the two-year trial run of the project endangered the lives of crew members and forced its leaders to inject huge amounts of oxygen […] The cause of the life-threatening deficit, scientists now say, was a glut of organic material like peat and compost in the structure’s soils. The organic matter set off an explosive growth of oxygen-eating bacteria, which in turn produced a rush of carbon dioxide in the course of bacterial respiration.

Considering a Martian city would need to rely on the same closed system technology as Biosphere 2, It seems that a necessary first step for a permanent community on Mars would be to demonstrate the ability to develop a reliable, sustainable, and safe closed system. I reached out to William F. Dempster, The Chief Engineer for the Biosphere 2. He has been a huge help and provided tons of papers that he authored during his time on the project. He was kind enough to point out some of the challenges of building closed systems intended for long-term human habitation:

What you are contemplating is a human life support pod that can endure on its own for generations, if not indefinitely, in a hostile environment devoid of myriads of critical resources that we are so accustomed to that we just take them for granted. A sealed structure like Biosphere 2 [….] is absolutely essential, but, if one also has to independently provide the energy and all the external conditions necessary, the whole problem is orders of magnitude more challenging.

The degree to which an off-planet lifeboat would lack resources compared to a terrestrial one would be dependent on the kind of disaster scenario that occurred, in some cases such as pandemic, it could be feasible to eventually venture out and recover machines, possibly some foods, and air and water (all with appropriate sterilization). While in the case of an asteroid strike or nuclear war at a civilization-destruction level, the lifeboat would have to be resistant to much the same conditions as an off-planet colony, as these are the kind of disasters where the Earth could conceivably become nearly as inhospitable as the rest of the solar system. To provide similar levels of x-risk protection as an off-planet colony in these situations, the terrestrial lifeboat would need to be as capable as Dempster worries.

While Biosphere 2 is in many ways a good analogue for some of the challenges a terrestrial closed system would face, There are many differences as well. First, Biosphere 2 was intended to maintain a living, breathing, ecosystem, while a terrestrial lifeboat would be able to leverage modern technology in order to save on costs, and the cost for a terrestrial lifeboat is really the biggest selling point. A decent mental model could be a large, relatively squat building, with an enclosed central courtyard. Something like the world’s largest office building. It cost 1 billion dollars in today’s money to build, and bought us 6.5 million sq ft of living space. Enough for 4000 families to each have a comfortable 2 bedroom home. A lifeboat would have additional expenses for food and energy generation, as well as needing medical and entertainment facilities, but the facility could have a construction cost of around $250,000 per family. The median US home price is $223,800.

There is one additional benefit that can’t be overlooked, Due to the closed nature of the community, the tech centric lifestyle, and combined with the subsidized cost of living. There is a natural draw for software research, development, and technology companies. Creating a government sponsored technology hub would allow young engineers a small city to congregate, sparking new innovation. This wouldn’t and shouldn’t be a permanent relocation. In good times, with low risks, new people could be continuously brought in and cycled out periodically, with lockdowns only occurring in times of trouble. The X-risk benefits are largely dependent on the facilities themselves, but the facilities will naturally have nuclear fallout and pandemic protection as well as a certain amount of inclement weather or climate protection. Depending on the facility, There could be (natural or designed) radiation protection. Overall, a planetary system of lifeboats would be able to survive anything an offworld colony would survive, outside of a rogue AI or grey goo scenario. But simultaneously the facilities would have a very low likelihood of a system failure resulting in massive loss of life the way a Martian colony could.

V.

To conclude, we decided that terrestrial and off-planet lifeboats offer very similar amounts of protection from x-risks, with off-planet solutions adding a small amount additional protection in certain scenarios whilst being markedly more expensive than a terrestrial equivalent, with additional risks and unknowns to the construction process.

The initial advocate for off-planet colonies now concedes that the additional difficulties associated with constructing a space colony would encourage the successful construction of terrestrial lifeboats before attempts are made to construct one on another body. The only reason to still countenance their construction at all is an issue which revealed itself to the advocate for terrestrial biospheres towards the end of the collaboration. A terrestrial lifeboat could end up being easily discontinued and abandoned if funding/political will failed, whereas a space colony would be very difficult to abandon due to the astronomical (pun intended) expense of transporting every colonist back. A return trip for even a relatively modest number of colonists would require billions of dollars allocated over several years, by, most importantly, multiple sessions of a congress or parliament. This creates a paradigm where a terrestrial lifeboat, while being less expensive and in many ways more practical, could never be a long term guarantor of human survival do to its ease of decommissioning (as was seen in the Biosphere 2 incident). To be clear, the advocate for terrestrial lifeboats considers this single point sufficient to decide the debate in its entirety and concedes the debate without reservation.