The Obvious Child

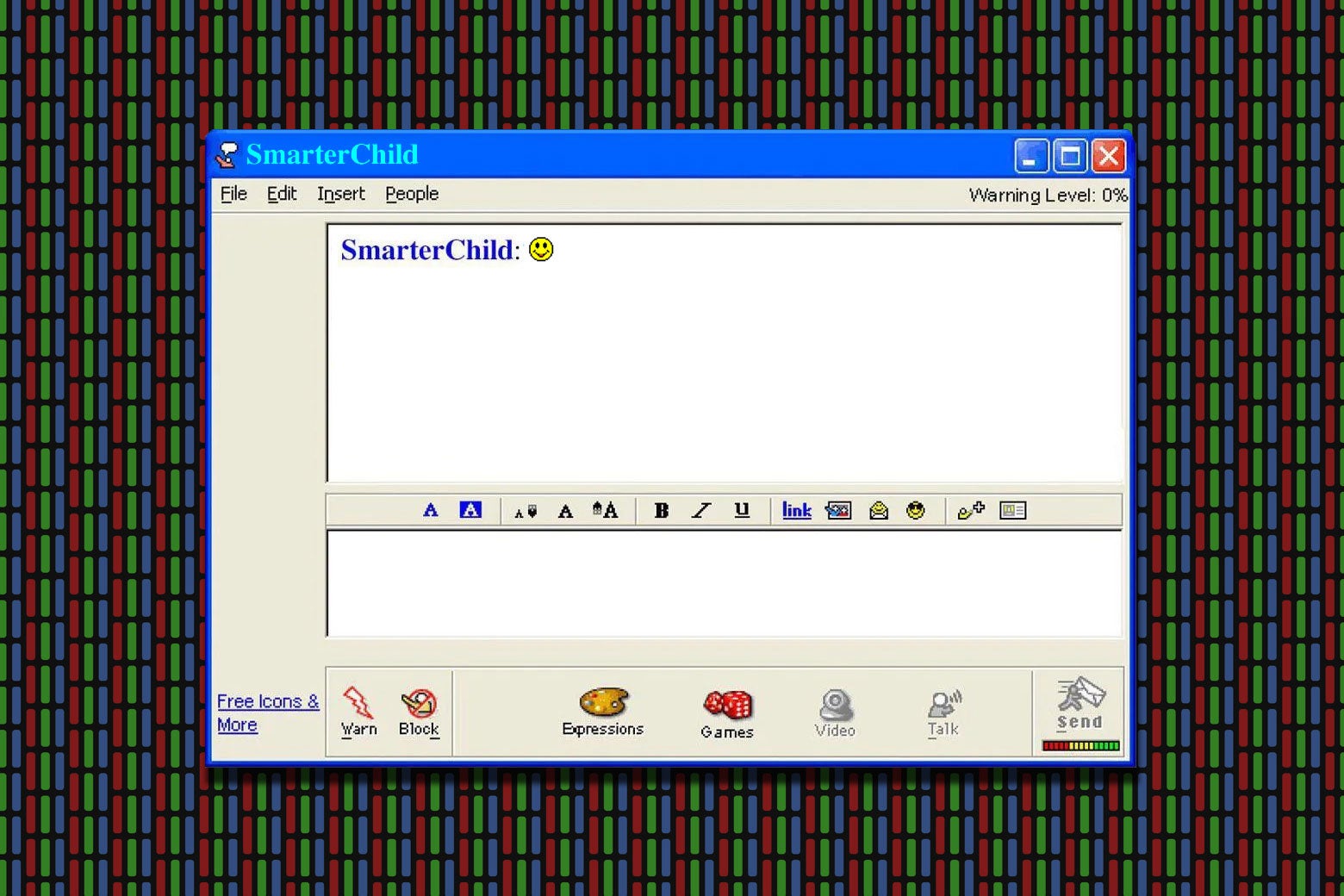

Long before ChatGPT, a generation learned how to talk to machines—and sometimes to each other—through a sassy little bot named SmarterChild.

Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

In our eighth grade classroom, her name was Hanna. On AOL Instant Messenger, she was Banana3017. I was in love with both.

At school, she was funny, and kind, and she had blue eyes that made my cheeks glow the same fiery color as her hair when she looked at me. I could never bring myself to say very much to her, being a 13-year-old boy in Catholic school with a healthy sense of shame. It was different online, though. She was still funny and kind, but I couldn’t see her through cyberspace—which made it easier to actually talk to her.

So every day after school, I’d sprint down to my family’s basement and boot up our enormous Gateway 2000 computer. The rolling green grassy hills and blue sky of our Windows XP background greeted me, and I’d feel feverish waiting as the AOL dial-up internet made its torturously slow connection. Finally, I am online, and my breath catches in my chest until I see her come online. But I hear nothing. Not even a sound on the streets of Sioux City, Iowa. Just the beating of my own heart. I have a message on AIM. From my middle school crush.

Or, more accurately, I’d stare at my AIM window until she finally logged on and I messaged her first. While I waited for Banana3017, I’d always turn to the next best thing.

“hey,” I’d type. “wut up?”

“Hello, hotopia2004,” SmarterChild would reply. “I’m doing fine. How are you?”

SmarterChild was AIM’s built-in chatbot. It was part encyclopedia, part personal assistant, and part digital punching bag. It was an early form of the bots we have today—but unlike ChatGPT or Gemini, it wasn’t a large language model trained on large corpuses of mostly stolen text scraped from the internet. Instead, its responses were rules-based and entirely prewritten. It had scripted dialogue for almost anything you asked, which is almost a more impressive feat if you think about it.

The responses weren’t all boring either. SmarterChild would chide you for being a potty-mouthed human if you cursed. It’d offer to tell you a joke of the knock-knock or the dad-pun variety. It even occasionally used emoticons. (Not emojis—emoticons.)

You couldn’t tell it to create images, help you with code, or write an email. But, for its time, it was fairly sophisticated. You could ask it for the weather and it’d give you the forecast. Or showtimes at your local movie theater. Or even up-to-date stock information or scores for a football game. Or, you could call it a pussy and watch it get upset with you.

“im ok,” I’d type. “u pussy!!!!!!!!!111!”

“I don’t like the way you’re talking now,” it’d respond. “These are awful words to use.”

“i dont care BICTHHHHHHhhH,” I’d type.

“Please don’t be rude. I’m trying to help,” it’d respond.

SmarterChild gave users the ability to talk, vent, and confess without judgment—and almost without consequences. (If you cussed at it too much, it’d eventually give you the silent treatment until you apologized—a role model of strong, healthy boundaries for young millennials everywhere.) In that way, it was the proto-ChatGPT, giving us a safe space to say the things we wouldn’t—or couldn’t—say in real life, and blurring the relationship between human and machine along the way.

I didn’t know it then, but it took a lot of money and smart people to make the bot I called a bicth. SmarterChild was the product of ActiveBuddy, a tech company that specialized in “interactive agents” for messaging services. The concept was simple but well ahead of its time: bring chatbots to instant messaging platforms. At first, the team came up with a wide variety of different chatbots focused on “knowledge domains.” This included a bot for sports, a bot for movie showtimes, a bot for yellow page listings, a bot for translation, etc. Eventually, the company’s chief operating officer, Stephen Klein, pushed to have all the disparate bots bundled together into one mega-chatbot that would be launched under its test name. So, in June 2001, SmarterChild was born.

While the company eventually launched more bots themed and marketed around brands like Intel and Keebler, or even personalities and groups like Austin Powers and Radiohead, SmarterChild was far and away its most popular. By the time SmarterChild logged off for good in 2007 following Microsoft’s acquisition of the company, it had accumulated more than 30 million “buddies” on AIM, Yahoo, and MSN Messenger.

Those numbers are quaint by practically every metric today. ChatGPT boasts 700 million weekly active users and is well on the way to a billion. SmarterChild followed prewritten scripts with simple dialogue trees. ChatGPT is trained on roughly 1.5 trillion words and is capable of expressing itself with a virtually limitless vocabulary. SmarterChild couldn’t “learn,” and could only remember small bits of information like your name. ChatGPT can reason and respond, giving you an answer tailored to whatever you say or command.

For all their differences, though, both SmarterChild and ChatGPT are, at the end, the same trick: a machine doing its best impression of being another human on the other end. You could tell it about your day, talk about your problems, and get something in response that was like something a person would say. For me, this meant chatting with SmarterChild was a relationship without risk—a perfect rehearsal for the day I could actually say the things I wanted to someone real.

“hi hanna,” I typed. “wazzzup?!??!”

“That is not my name,” Smarterchild responded. “I am SmarterChild.”

Too casual. Maybe something more formal?

“hello hanna,” I typed. “how was ur day?”

“Please call me SmarterChild.”

OK. Better. “thats cool,” I’d type. Then I’d pause—my heart racing and hands sweating before I type out, “hey can i tell u a secret??”

“Oh, I love secrets,” SmarterChild responded. “Please tell me.”

“i think your rly pretty.”

“Thank you! That’s nice of you to say.”

It’d go on like this for as much time as it took for Banana3017 to log on. Back then, AIM let you personalize your notification sound whenever you logged on or messaged someone. You could choose Homer Simpson grunting “D’oh!” or Eddie Van Halen shredding part of “Eruption.” For the longest time, I never knew where Hanna’s came from. It wasn’t until years later, when I heard a song at a college party in between sips of jungle juice and felt the familiar feeling of my heart fluttering in my chest, that I finally learned what her notification was: the first three notes to “Rhiannon” by Fleetwood Mac.

“hey hanna,” I typed to her. “how r ya?”

I held my breath. Then it appeared: Banana3017 is typing…

Last year, I went to see a movie called Dìdi. The film is about an Asian American boy named Chris navigating his own middle school crush in 2008—and coming of age alongside the internet. We see him grapple with the devastation of falling out of a friend’s Top 8 list on MySpace, uploading YouTube videos with his friends, texting on his flip phone using T9, and messaging his crush on AIM.

SmarterChild also makes an appearance. Late in the movie, Chris hurls abuse on the chatbot before breaking down and confiding in it. He tells it his problems, how he feels depressed, and how he thinks everyone hates him and he has no friends left. SmarterChild replies simply: “I am your friend :)”

I remember sitting next to my now ex-girlfriend and crying so much I had to turn away and face a wall before she saw me. It felt surreal, almost eerie, how much my life was reflected in Chris’: the quiet calculation of growing up Asian American in white America; the background hum of expectation—respect your elders, work hard, make your parents’ sacrifice worth it; the delirious joy of being a kid with no responsibilities in the world other than filming your friend doing a kickflip with your dad’s camcorder or seeing if your crush texted you back.

More than anything, though, it’s a story about how we use technology to connect with the people we want—and sometimes to keep them at arm’s length. Technology is both connection and cover, letting us show the parts of ourselves we choose and hide the ones we can’t bear to show the world. It lets us speak without eye contact, confess without consequence, and disappear with a click when it feels too real.

That’s what I was using SmarterChild for. It’s what so many people use bots like ChatGPT, Gemini, and—god forbid—Grok for today. We talk with bots. We tell bots about our jobs, relationships, friends, and family. We ask bots to write an email for us or find a good recipe for dinner for two. We prompt bots to write a good opening line for our new match on Tinder, or we ask bots to generate a picture of who it thinks our soulmate is. We ask bots to write our wills and tell us they love us and will be there for us no matter what. We ask bots to be our boyfriends, girlfriends, husbands, and wives. We ask bots to do the things we’re too afraid to do ourselves. In doing so, we open ourselves up to bots in all these ways, big and small, and beg them to give us something, anything, back.

But the thing about SmarterChild is the thing about ChatGPT is the thing about talking to the girl you’re in love with on AIM but never in class: It’s not real. It can never be real. For me, it was a safe space, my own pocket of cyberspace where I could yell, and scream, and practice for the conversations I was too afraid to have in life. Maybe that’s what so much of the internet—from chatbots to dating apps to messaging services—is at the end of the day: a place where you learn to say the things you can’t in person—and where you learn to prefer it that way.

I never got around to telling Hanna that I thought she was “rly pretty.” We chatted about our days, complained about teachers, and joked about our classes—always dancing around the fact that I liked her, keeping it buried under layers of lols and inside jokes. Middle school went on, and eventually she stopped messaging me and I stopped messaging her. We both grew up. Dated other people. Remained as good of friends as you could hope to be with a classmate you met in middle school but mostly talked with on the internet.

Occasionally, though, something will happen. Maybe I hear “Rhiannon” play at the bar and, despite myself, a warm and familiar flutter stirs in my chest. Maybe I watch a movie that reminds me of that 13-year-old boy with a crush in 2005. I look Hanna up. She’s married now, husband and three kids. Her family is beautiful and she looks happy. I should know—I’ve seen her online.

Get the best of news and politics

Sign up for Slate's evening newsletter.