![]()

Photo illustration by Slate. Photos by Charles Kelly/AP Photo, John Duricka/AP Photo, Bettmann/Getty Images, and AFP via Getty Images.

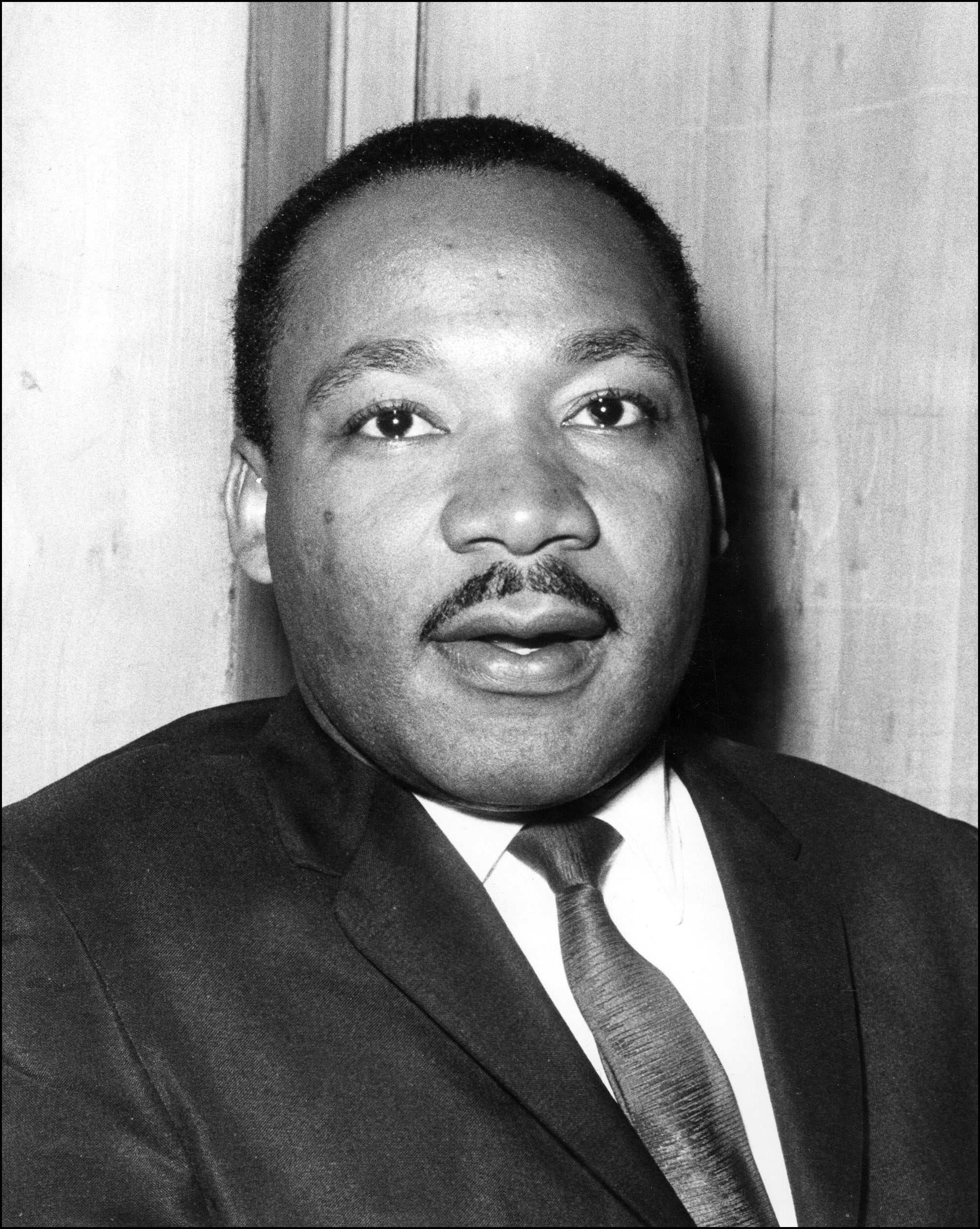

The Man Who Was Supposed to Kill Martin Luther King Jr.

For years, one man complicated the official story of who murdered the civil-rights leader. Just before he died in October, he offered a jaw-dropping revelation.

Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

On Saturday, Oct. 11, a man named Russell Byers died. He lived in Creve Coeur, Missouri, a suburb of St. Louis. He was 94 years old. He lived a rich and full life. He was a criminal for almost all of it.

Byers stole cars and precious art from the Saint Louis Art Museum. He was a fence. He is known to have threatened more than a few people, though he always maintained that he “didn’t kill people or deal drugs.” He believed that committing those crimes was too easy a way to end up in prison. Even though his own attorney said that Byers was “one of the most dangerous criminals” in St. Louis, and despite a life of a never-ending litany of criminal activities and many indictments, Byers never spent one day behind bars.

That said, none of this unlawful behavior became the reason for Byers’ brief notoriety. He came to national fame in the late 1970s as the recipient of what is known in criminal conspiracy circles as the Byers Bounty—a $50,000 offer to kill Martin Luther King Jr. The Byers Bounty has long been considered the key to understanding whether there was a broader undiscovered conspiracy to murder the civil rights icon. It is a theory about King’s assassination that many still believe, including several who investigated the crime.

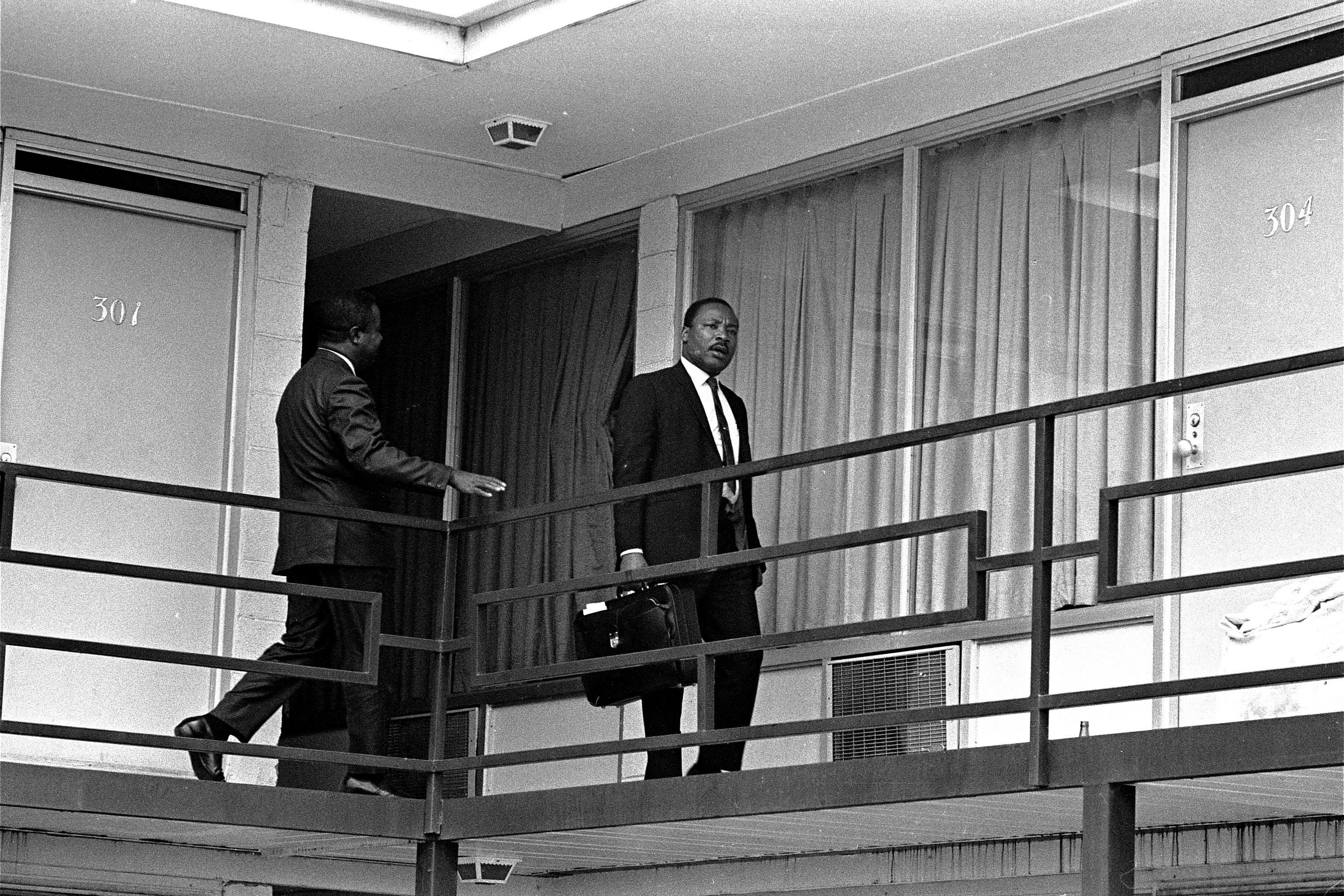

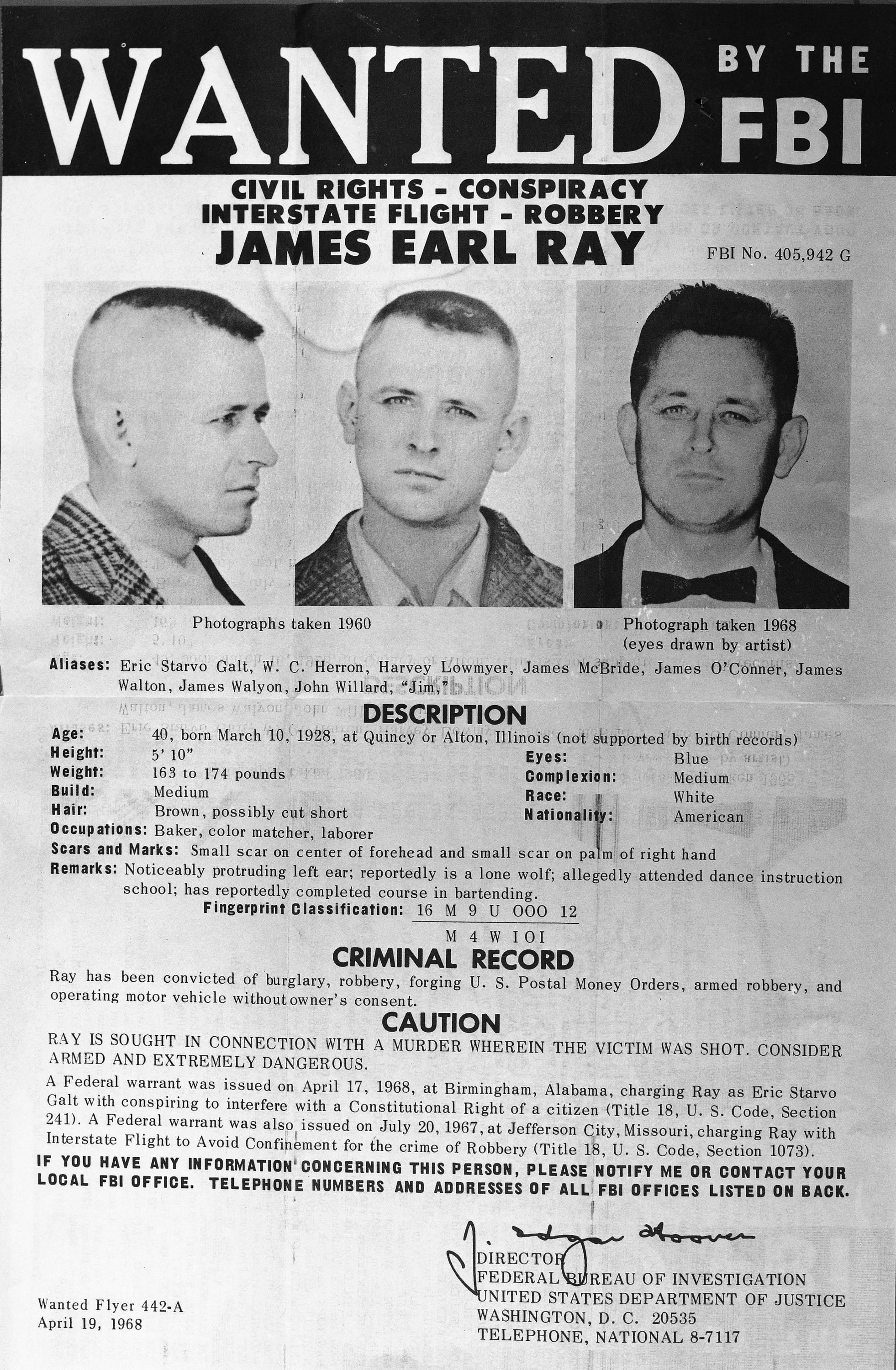

The official history of King’s death goes like this: The civil rights leader was assassinated on April 4, 1968, while standing on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel in Memphis, Tennessee. Initially, law enforcement agents believed they were searching for several possible killers. But two weeks after the murder, the FBI matched fingerprints found at the scene and announced that the fugitive assassin was one man, James Earl Ray, an escapee from the Missouri State Penitentiary.

On June 8, two months after King’s death, Ray was arrested by customs agents while attempting to board a flight to Brussels at London’s Heathrow Airport. Ray was extradited to the United States, and nine months after his capture, on March 10, 1969, he pleaded guilty to King’s murder. Three days later, he recanted that confession and spent the rest of his life professing his innocence, claiming that he was made a patsy for the real assassin, a man he called “Raoul.” Raoul was transparently fictitious, but that doesn’t mean that someone else, or perhaps several people, didn’t aid and abet Ray in what has always been a crime for which he alone was held accountable.

For over 50 years—both because of Ray’s continued protestations as to his innocence, and because of the stunning revelations about the FBI’s harassment of King during his lifetime—conspiracy theories have proliferated about who really killed the civil rights icon and why. Of all those theories, the Byers Bounty, alleging that a far-right Southern organization offered to pay to have King killed, is considered the most credible, and is the only one to have been backed by a full-blown congressional investigation.

For years after revealing this alleged bounty, Byers largely disappeared from public view, deepening the mystery surrounding King’s assassination. In fact, for most of this century, he was widely believed to already be dead by those with an interest in the King case. In my own years of reporting and research, I attempted to locate Byers numerous times to no avail. I, too, thought he was dead. That was until this past summer, when somebody reached out to me with his whereabouts, along with a note saying, “The man that brokered the murder of MLK is alive.”

A few months later, Byers was indeed dead—but not before I spoke to him one last time. What he told me, and what I discovered in tandem, added a chilling new dimension to a case many had long assumed would never be fully explained. There’s still one way it could be.

Over the years, Russell Byers discussed the alleged bounty to kill Martin Luther King Jr. at various times with a number of people, but he always maintained that he never had any involvement in the actual assassination. As Byers related the incident in 1978 in front of the House Select Committee on Assassination, the offer went like this: One afternoon in late 1966 or early 1967, John Kauffman, a friend of Byers’ and the owner of the Bluff Acres Motel in Imperial, Missouri, where Byers stored his stolen goods, asked him if he wanted to make $50,000 (or about $500,000 today). Byers said he was interested and asked him what he needed to do. All Kauffman would say was that they’d meet a man at 6:30 p.m. who would let him know.

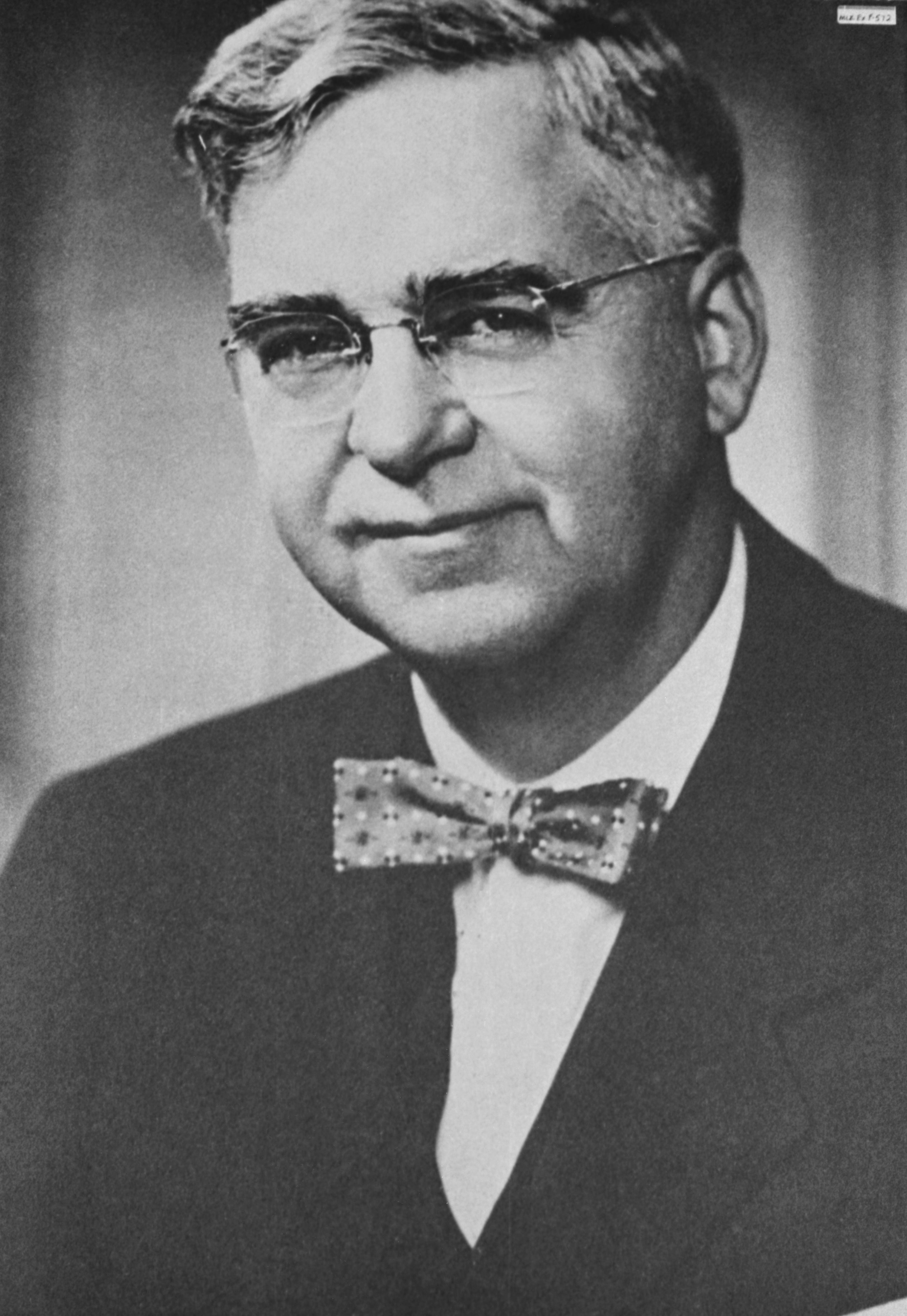

That evening, both men went to the home of John Sutherland, a well-to-do patent attorney who also lived in Imperial and who had his law office about 25 miles away in downtown St. Louis. When Sutherland met them at the door, he was outfitted in overalls and wearing a Confederate cap. Upon entering the living room, Byers noted the decor, which prominently featured Confederate flags and other rebel artifacts: bugles, swords, and additional antebellum paraphernalia. They exchanged pleasantries with Mrs. Sutherland, she departed, and the men got straight down to business.

Sutherland told Byers he would pay him $50,000 either to assassinate King or, as Byers later interpreted it, to arrange to have him executed. The offer made total sense to Byers. In the hierarchy of St. Louis criminals, Byers was right at the top, so if he didn’t commit the murder himself (always being one to avoid prison), he could definitely organize it. Indeed, Byers had a brother-in-law serving a life sentence at the Missouri State Penitentiary for a contract hit. Coincidentally, that brother-in-law was the cellmate of a man named James Earl Ray. Either way, Byers was certainly one of the few men in St. Louis who could deliver on the job, especially for that large an amount of money.

But Byers was a canny, cautious criminal. He told Sutherland that he didn’t know who King was. Sutherland informed him that King was a civil rights leader. Byers was intrigued and asked how he would get paid. Sutherland said that “he belonged to a secret Southern organization that could raise the money.” That “secret” organization might have been the Southern States Industrial Council, of which Sutherland was an active member. The organization funded many right-wing causes, from the staunchly anti-communist John Birch Society to the rabidly segregationist White Citizens’ Councils. Or it might have been a more loosely formed group of reactionary zealots.

Whoever the backers, Byers thought it seemed like the kind of business he normally avoided, being unwilling to risk prison. But he was afraid to say no immediately. As he later testified before the House Select Committee on Assassination, “I sort of crawfished a little. I seen too many late-night movies where they make you an offer you can’t refuse, and you jump up and shout out, ‘Absolutely, no,’ and you may never leave the place.” So, instead, Byers demurred and told Sutherland he didn’t think he’d be interested but that he’d consider it. Immediately upon leaving Sutherland’s home, Byers testified, he told his friend Kauffman that he definitely wasn’t interested. Indeed, Byers testified that by early 1968 all his interactions with Sutherland and Kauffman had come to a halt and he continued with his more typical criminal pursuits. This is where, according to Byers’ testimony, the trail appeared to end.

So it all seemed fairly straightforward: If Byers never shared the offer of the bounty with another living soul until after the murder, then it meant there was no direct proof that the Byers Bounty had played any part in King’s assassination. If, however, Byers had spoken about the bounty offer before the killing, that person would have been included in an information chain that linked Sutherland and Kauffman to Byers and potentially to Ray—making the assassination a possible conspiracy instead of the act of a lone gunman.

And this is where Byers’ testimony gets interesting. When questioned by members of the HSCA, Byers testified that he told only three people about the bounty offer—and none of them until after the murder. The first to know was his attorney, Murray Randall, whom he said he told in 1968, after King’s assassination. As Byers testified before the committee, “You had to tell somebody. You know, it just struck me rather strange. The man got killed, and I had the offer.”

Under waiver of attorney-client privilege in his own HSCA testimony, Randall countered and said that Byers didn’t tell him anything about the bounty until 1973, which he said he recalled vividly because he was just closing his practice and preparing to become a judge.

Byers disagreed. He recalled his thinking by saying, “Well, I ran it by him for one reason. He told me at the time the man had confessed to the killing or had been apprehended, and he told me evidently there was no substance to it, just to forget about it.”

According to Byers, that’s exactly what he did. He forgot about it—until some years later, when he told a second person, his new attorney, Lawrence Weenick. Weenick gave him the same advice as Randall had: Byers was not involved by simply having been offered a bounty.

Then there was a third man to whom Byers told of the bounty—this time, he testified, in 1973. He didn’t recall that exact conversation but reported: “I unconsciously had told someone about the offer, an informant to the FBI, and the FBI wrote it down.”

This was as vague as Byers had ever been during the HSCA hearing. But this 1973 meeting raised the interest of committee investigators, because there was an informant report with the full story about the bounty offer from 1973 that had been put into Byers’ FBI file—and, for some reason, was not sent on to FBI headquarters in Washington to be considered in the still-open investigation of King’s assassination.

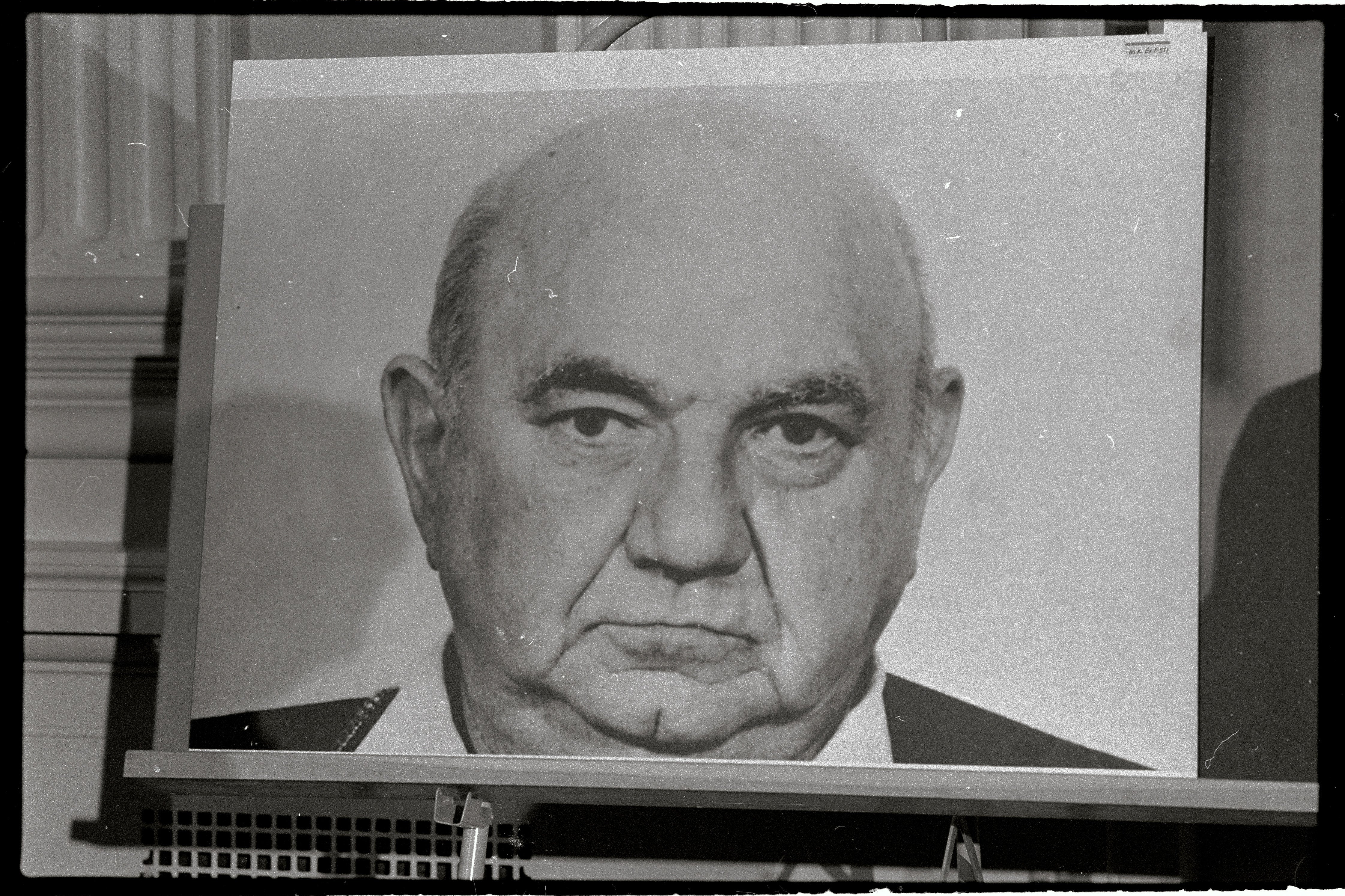

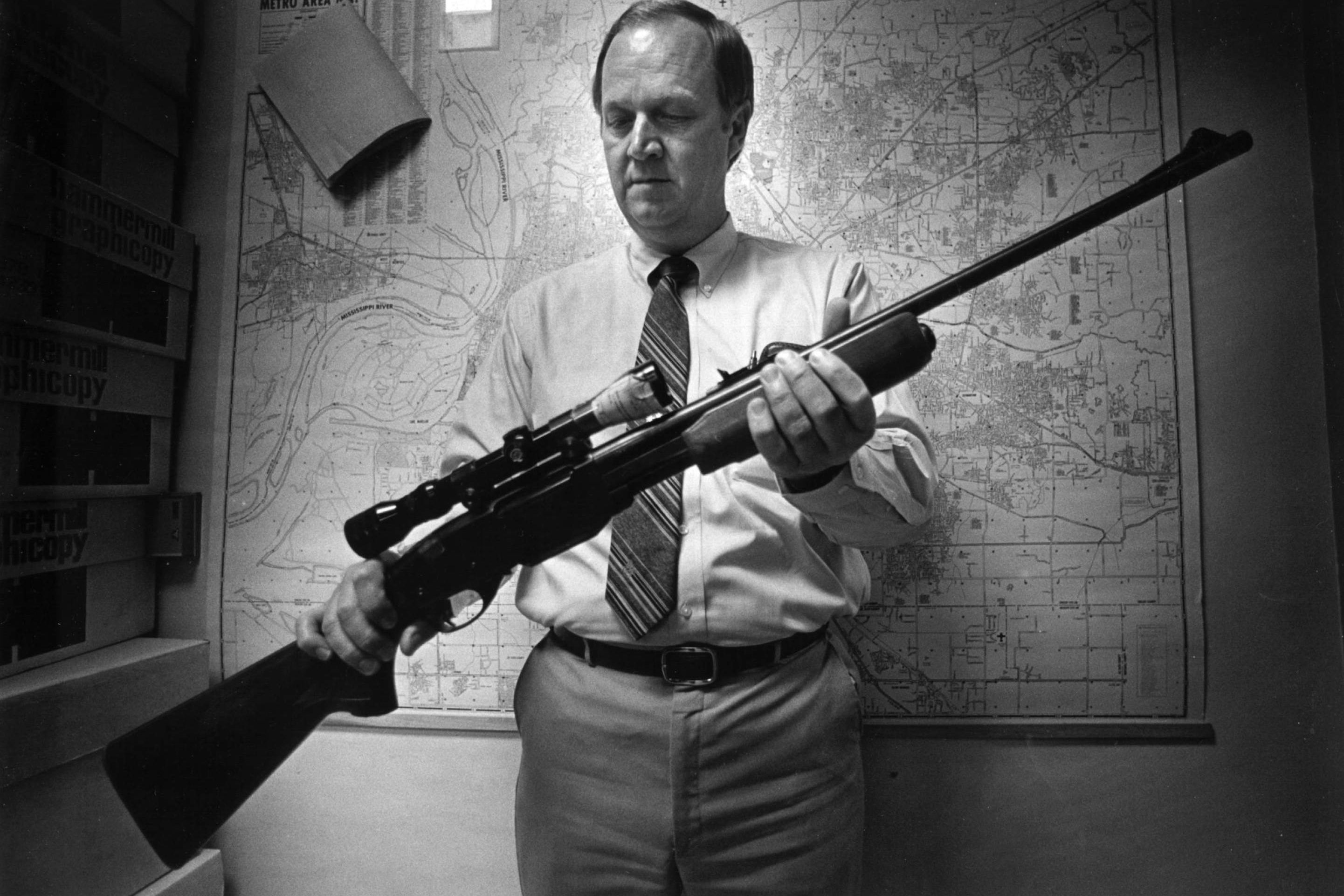

Five years later, in 1978, when Byers was under scrutiny by the FBI in St. Louis for yet another federal crime, the informant report was unexpectedly discovered in his file. William Webster, the then director of the bureau and a former St. Louis judge, immediately sent the long-lost memo to Washington. The HSCA investigation was in full swing, and Russell Byers now found himself in the crosshairs of a congressional investigation into King’s murder.

That 1973 informant report ignited what had been, up until that point, a plodding and inconclusive investigation into what had already been known about King’s murder. But upon reading the newly discovered memo, HSCA chief counsel Robert Blakey concurred with Byers’ assessment: “It struck me awfully funny that I get the offer and the man turns up dead. Either it was connected, coincidental, or everybody was out to kill [King]. One of the three.” Blakey, emboldened with the trail laid by the Byers Bounty, was determined to find out which of the three it was.

The HSCA’s full report was derived from both open and closed testimony, depositions, interviews (including 10 conducted with the unnamed 1973 confidential informant), and thousands of pages of documents. All the closed-session testimony, the depositions, the interviews, and many of those documents are still under seal, unavailable to the public for at least 50 years—potentially becoming available only in 2027. Many believe that these materials will never be released.

All told, the public report from the HSCA, along with later statements made by Blakey, provide a compelling circumstantial case as to how the Byers Bounty might have been the lynchpin for James Earl Ray’s decision to assassinate King. Without the full files, however, it is difficult for the public to know how circumstantial.

What we do know without access to those files is this: Using what is known as a “link analysis,” the committee created four potential scenarios by which the bounty offer could have been communicated from Sutherland, Kauffman, or Byers into the Missouri State Penitentiary where James Earl Ray was then incarcerated and from which he was soon to escape.

The epicenter of the HSCA’s analysis focused on the Grapevine Tavern. Located on Arsenal Street in South St. Louis, the Grapevine was the favored watering hole for the local right-wing criminal underworld. It was the kind of place you could pick up a “George Wallace for President” pamphlet at the bar and get a lead on your next heist while drinking a Falstaff beer advertised on the sign outside. The Grapevine Tavern was owned by John Ray, James Earl Ray’s closest brother.

All the potential scenarios outlined by the HSCA, though, belied Byers’ testimony. He swore under oath to the committee that he didn’t tell anyone about the bounty until after Ray had already murdered King.

Timing, in this case, is everything. If Byers had told someone about the bounty before the assassination, the question of who was involved in aiding and abetting James Earl Ray in a conspiracy to kill King could well be wholly different from what anyone has considered in the past 50 years.

The HSCA’s link analysis about the Grapevine Tavern and its conclusion that the Ray family was deeply involved in the plan to assassinate King were never pursued by the Department of Justice. It was too circumstantial, some people said. The FBI, which had done quick work under J. Edgar Hoover in both the shooter investigation and the fugitive investigation, had failed to conduct any conspiracy investigation at all—most likely in an attempt to keep information about the FBI’s extensive subversion of King from coming to light. By the time the HSCA report came out in 1978, the DOJ seemed loath to reopen that deeply scarred period in the bureau’s history. And many believed that by the late ’70s, too many of the witnesses, including Sutherland and Kauffman, had died to make a solid case.

And then the trail went even further off track when, in 1997, Dexter King visited James Earl Ray in Brushy Mountain State Penitentiary, shook his hand, and said he didn’t think Ray had ever pulled the trigger that killed his father. Unfortunately, that’s where the King assassination debate has been mired for the past 25 years.

I have been studying the right-wing criminal underworld in St. Louis for more than a decade. I have published on the subject. Sometimes I do interviews and audio shows about the connections I have uncovered. I have spent hours combing through the printed hearings of the HSCA, reading FBI memorandums from the MURKIN (Murder of King) files, and speaking to key participants in the HSCA hearings, in particular Blakey, the chief counsel, whom I have interviewed three times. I have steered clear of the conspiracy rabbit holes that many self-proclaimed experts on the subject have spent years digging.

My research, like the HSCA’s, has relied upon the same basic set of facts about who beyond Byers was told what—and when they were told—about the Byers Bounty: three people, all told after the assassination.

In July, and in concert with the recent release of over 243,000 pages of King FBI files, I did an interview with St. Louis Magazine about my ongoing research. Then, on July 28, at 8:38 p.m., I received the following email:

Hello.

The man that brokered the murder of MLK is alive and lives in St Louis county.

He’s quite old, in failing health, and eager to (finally) tell his story.

I’ve known him since 1973.

His name is Russell George Byers. …

If you’d like to speak with him, please call me. I’ll happily make the introduction.

Being a lifetime criminal and world class art thief, he has countless stories.

As a historian and a journalist, I get a lot of crazy communications, most of which I ignore. But this one piqued my interest. I had been told by many reliable sources that Byers had died quite a while ago, and my own extensive research had suggested the same.

This lead seemed worth pursuing. Sure enough, soon I found myself on the phone with Byers, living at the home of his stepdaughter on Fredric Court in Creve Coeur, age 93 and soon to have a toe amputated due to neuropathy. He was sharp and lucid and, yes, ready to talk.

Over the course of several conversations, I told Byers that we had to do what I called a “preinterview” before I came to St. Louis with a camera crew so that I could formulate a series of pointed questions that would make the best use of his time and my resources. He was game for that and allowed me to tape our conversation for my notes.

During that recorded conversation, concerned about Byers’ age and mental acuity, I went back through many of the same questions that he had been asked by the HSCA—who had made the offer, what relationship he had with John Kauffman, the details of the bounty offer, and so on. He recounted to me the same answers he had given nearly 50 years ago. I was somewhat reassured that his memory was still relatively intact.

Then I asked whether he had mentioned the bounty offer to anyone else.

To which he responded: “Yes, I told it to the guy with the antique store down on Maryland Avenue. He was a federal informant.”

I was taken aback. “When did you tell him that?”

He responded, “Right after I come from Kauffman with the offer. I come in the door, and he says, ‘I wanted to see you. I want you to kill a guy in Chicago for me.’ I says, ‘I don’t kill people,’ I says. ‘I just got the offer to kill King.’ He says, ‘Martin Luther?’ I says, ‘Yeah.’ ”

I pressed him further. “Do you think he told other people?”

Byers said, “He was a federal informant. That’s what he was. It’s the FBI’s fault that they did not act on this offer. Do you understand me?”

Not really believing what I was hearing—both because it diverged so much from the testimony he had given to the committee and because of his age—I assumed he was simply confused about the timing of it all, so I pushed him again.

“But didn’t you mention it to him a long time after the offer was made? Like, maybe in ’73?”

Byers was insistent. “It was five minutes after the offer was made. I went straight to the store because we were dealing in stolen lamps and stuff. And he told the FBI immediately. They should have acted upon it. He would still be alive.”

I pressed him once more: “According to the FBI, you didn’t mention it to an informant until five years later.”

Byers was clear: “No, it was five minutes later. The FBI was on my back. I left Kauffman, and I went to the informant. If they had acted on it, he would be alive.”

Sitting on the couch in my home office, I was stunned. I ignored, for a moment, the FBI’s failure to investigate any potential conspiracy once it had arrested Ray because of its own misdeeds in the ever-growing COINTELPRO domestic-spying scandal. I put to the back of my mind the revelations about Hoover’s known assaults on the civil rights leader while he was alive. I stripped away all of the complexity and merely pondered the possibility that Byers was telling the truth now and that he had lied before the HSCA; he had confided about the bounty to someone who both was an FBI informant and was highly active in the St. Louis criminal underground, a network deeply aligned with far-right-wing politics. The agency’s failure to investigate a conspiracy to kill King could have been one of the most fateful errors of inaction in the history of our nation.

Again, the timing of Byers’ revelation to others is critical. If money was Ray’s motivation for the assassination, then his knowledge of the bounty in 1967, while he was still incarcerated in the Missouri penitentiary, could well link the Ray family (and potentially others in St. Louis’ right-wing political and criminal circles, much of which overlapped) to the aiding and abetting of the murder. It would make the question “Who killed Martin Luther King Jr.?” a conspiracy instead of the lone-wolf assassination that the FBI has always asserted it was.

Strengthening Byers’ new contention that he had indeed told the criminal underworld in St. Louis—and, via the informant, the FBI as well—long before the assassination was a May 8, 1968, memorandum from the Birmingham FBI field office to J. Edgar Hoover that came during the hottest point of the Ray manhunt. It is a piece of information that has bedeviled me since I read it 10 years ago, as I could never quite figure out where and how it fit into the timing of events. In it, the special agent in charge recounts an interview done with one of Ray’s cellmates in the Missouri penitentiary who reported Ray having said to him:

I have a plan and when I get out, I am going to make big money, and it is not going to be robbing banks. The businessmen’s association has offered one hundred thousand dollars for killing Martin Luther King and he’s five years past due.

There was no way that Ray’s cellmate could have known about a bounty being offered by a businessman’s association unless someone, such as Ray, told him—especially given its specificity (except for an inflation of the amount of money to be paid). That the cellmate used the same language as Sutherland about the “businessman’s association” paying the bounty—at a time when the Byers Bounty was not known by the public and would remain unknown for more than a decade—reinforces the cellmate’s statement to the FBI that Ray knew of the bounty and intended to act upon it.

Even with this corroboration, I still worried about the veracity of what Byers was telling me, especially when he began speaking about the committee hearing itself. He began discussing something about a Watergate prosecutor, as if I should know what he was referring to. It sounded like total gibberish to me, and it convinced me that his memory of the timing of his testimony, about whom he told about the bounty and when, was correct back in 1978 and not now in 2025.

But then I thought, What if he’s telling me about something I don’t know? So I researched further and, sure enough, what he was telling me made much more sense than I had originally thought. I just hadn’t known anything about it.

When Byers testified before the HSCA, both in closed and open session, he was represented by an attorney named James Hamilton. Byers initially did not want to testify at all, believing his life to be in danger and fearing that he might incriminate himself. He was subpoenaed to testify and offered a grant of immunity for his testimony. He was guarded by the FBI throughout his entire stay in D.C. In the hearing room, the committee took the additional precaution of requiring the attendees to remain seated until Byers was escorted in and out by a cadre of armed agents. The only other HSCA witness afforded such protections was James Earl Ray himself.

In 1978, Byers had a St. Louis attorney, Terry Crouppen, who had been a public defender and who was about to launch his own law firm. According to Byers, he was told to send Crouppen home and that his attorney would be replaced with Hamilton. Byers recounted to me an odd story that someone he didn’t know called him in the middle of the night and told him that he would be given this new representation. It all sounded muddled and delusional. But Byers added that Crouppen refused to forgive him for relieving him of his representation in front of the committee and never spoke to him again. I checked further and, indeed, Hamilton had served as the assistant chief counsel to the Watergate Committee and became Byers’ personal attorney just before his testimony in front of the HSCA. In the words of Byers, “How does a nothing like me end up with a Watergate prosecutor?” Interesting question. Maybe the 93-year-old was more lucid than I thought.

I arranged to interview Byers at his home in St. Louis on Aug. 19, his 94th birthday. On Aug. 10, I began receiving phone calls from him asking to be compensated for his interview. I explained to him that this wasn’t possible, that journalists do not pay for interviews, that it is unethical. Trying to explain journalistic ethics to a lifelong criminal was probably a fool’s errand, but I still tried. He insisted that he wanted $75,000. I declined, and that’s where our interactions ended. And now he is dead. But I have the tape of our conversation.

What is most important now—especially given the distinct possibility that Byers lied to the HSCA in 1978 about his never having mentioned the Byers Bounty until after King had already been assassinated—should be the hastened release of all the documents relating to the King assassination. The FBI files released this past summer are just the beginning, a fraction of what the bureau generated. And there are thousands of pages of HSCA files still under seal. These include the extensive interviews the committee conducted with the informant, the closed-door (and perhaps more candid) testimony of Russell Byers, John Ray, another brother Jerry Ray, and James Earl Ray, among others. There are still-secret depositions and additional investigative interviews that should see the light of day. As recent news events have shown, public pressure can go a long way to compel the FBI to do the right thing. If there was a successful conspiracy to assassinate King that spread from Russell Byers to the Grapevine Tavern and the Ray family to James Earl Ray, the American public—and the King family—has the right to know.