What if you could beat LLM’s planning performance with a model that's 160,000 times smaller and 55 times faster? That's exactly what SCOPE (Subgoal-COnditioned Pretraining for Efficient planning) achieves.

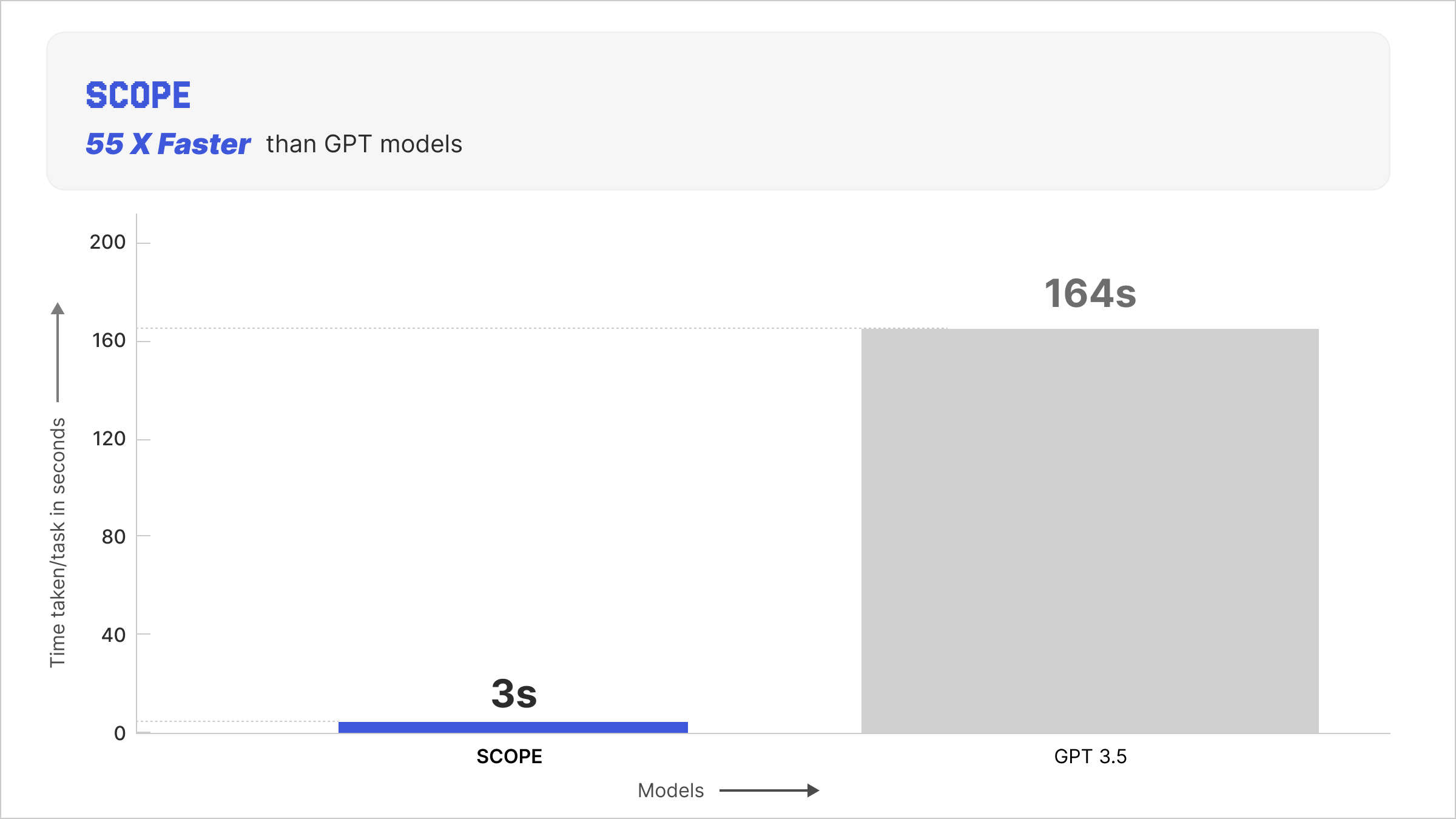

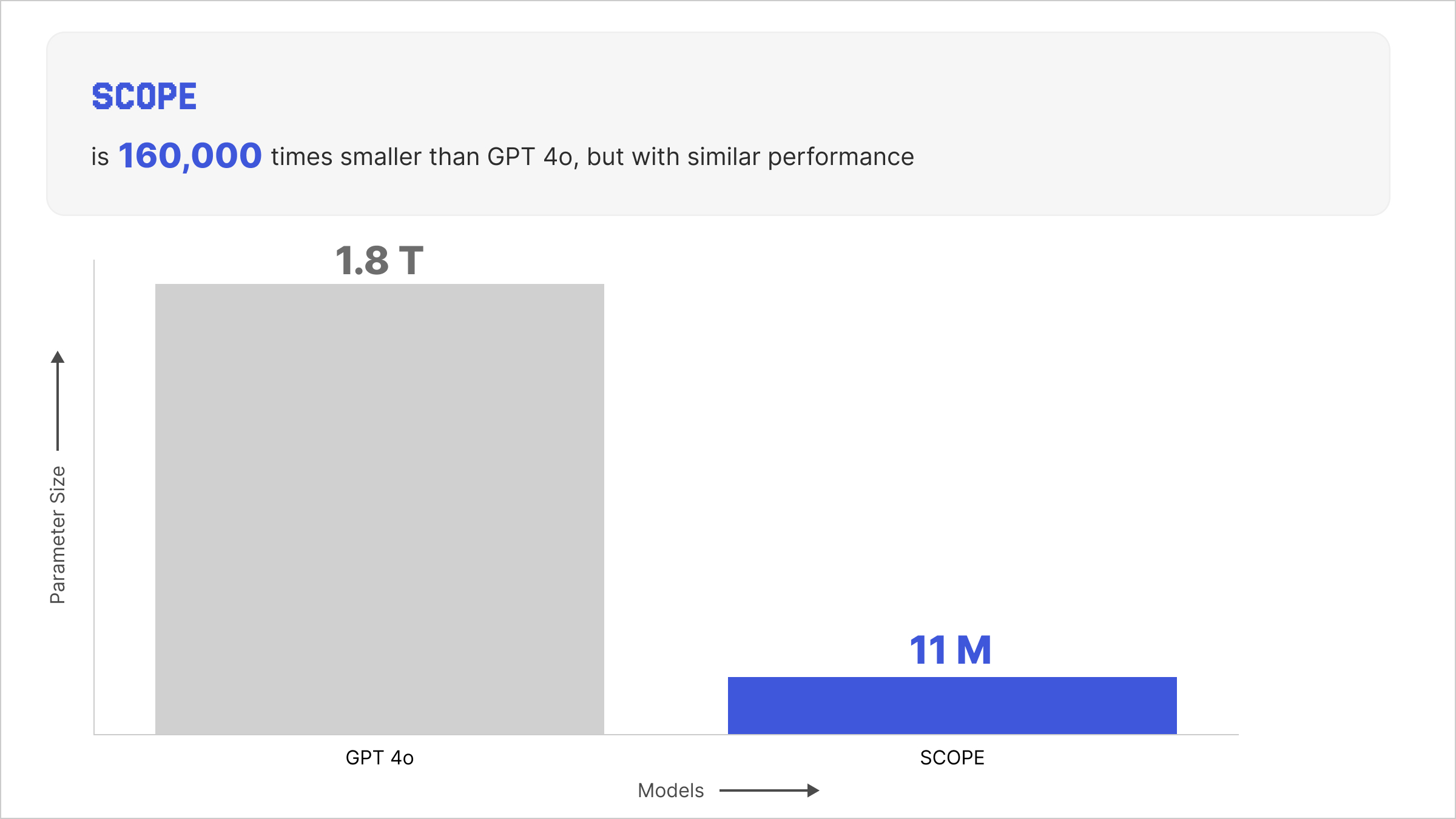

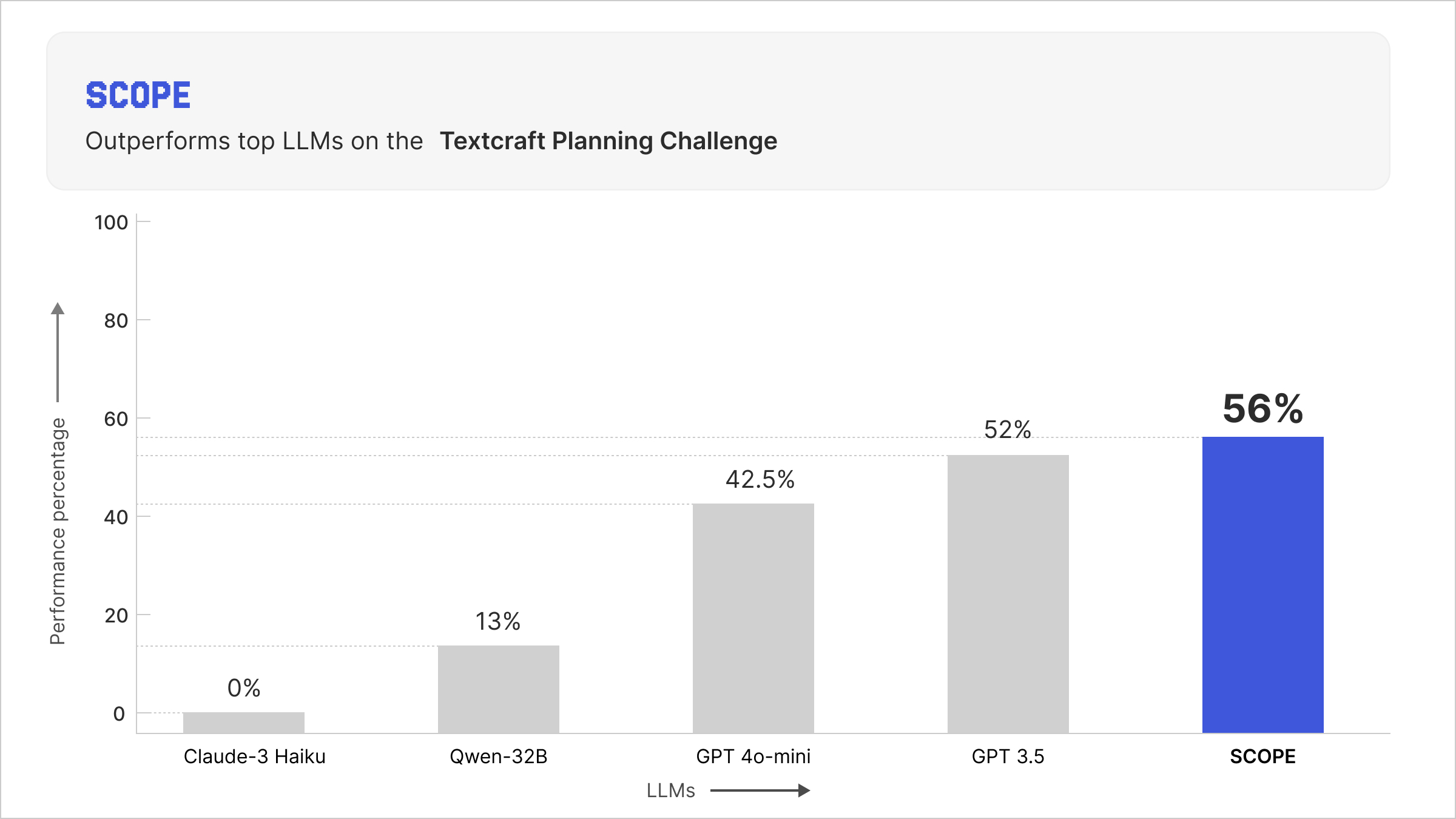

Our new approach delivers a 56% success rate compared to a baseline LLM’s (ADaPT) 52%, representing an 8% improvement. At the same time, SCOPE completes tasks in just 3 seconds (on a single NVIDIA A10 GPU) versus 164 seconds for ADaPT, making it 55 times faster. The model itself uses only 11 million parameters, which is 15,000 times smaller than ADaPT (having 175 billion parameters). Additionally, SCOPE has a similar performance as GPT 4o which has 1.8T parameters (160,000 bigger that of SCOPE). Most importantly, after a one-time initialization, SCOPE incurs zero API costs and requires no network dependency for deployment.

SCOPE isn't just an efficient alternative to LLM-based planning. It's a better solution that happens to be dramatically more practical to deploy.

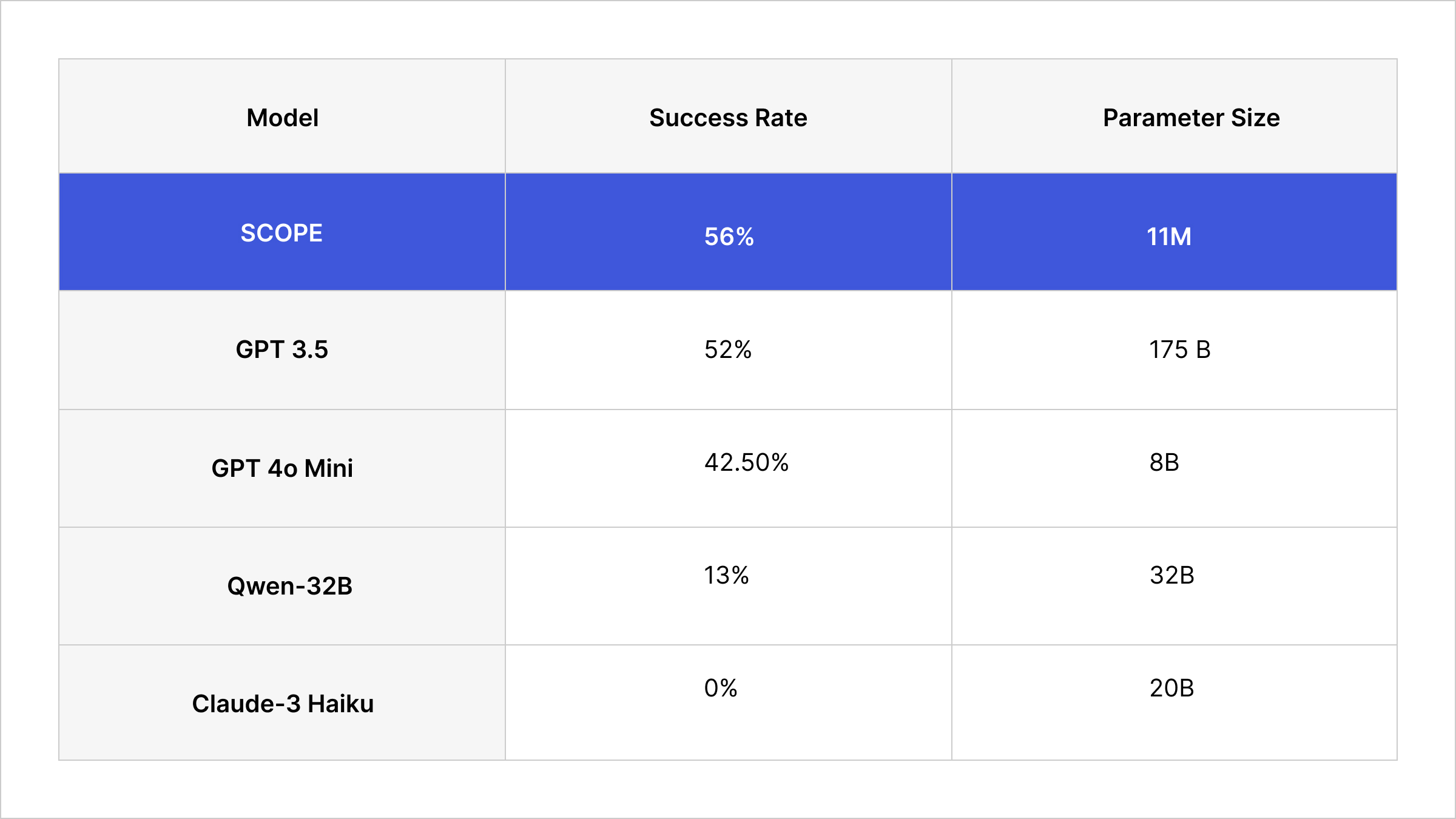

Figure 1: Comparison of Frontier LLM vs Scope for parameter size and success rate on TextCraft

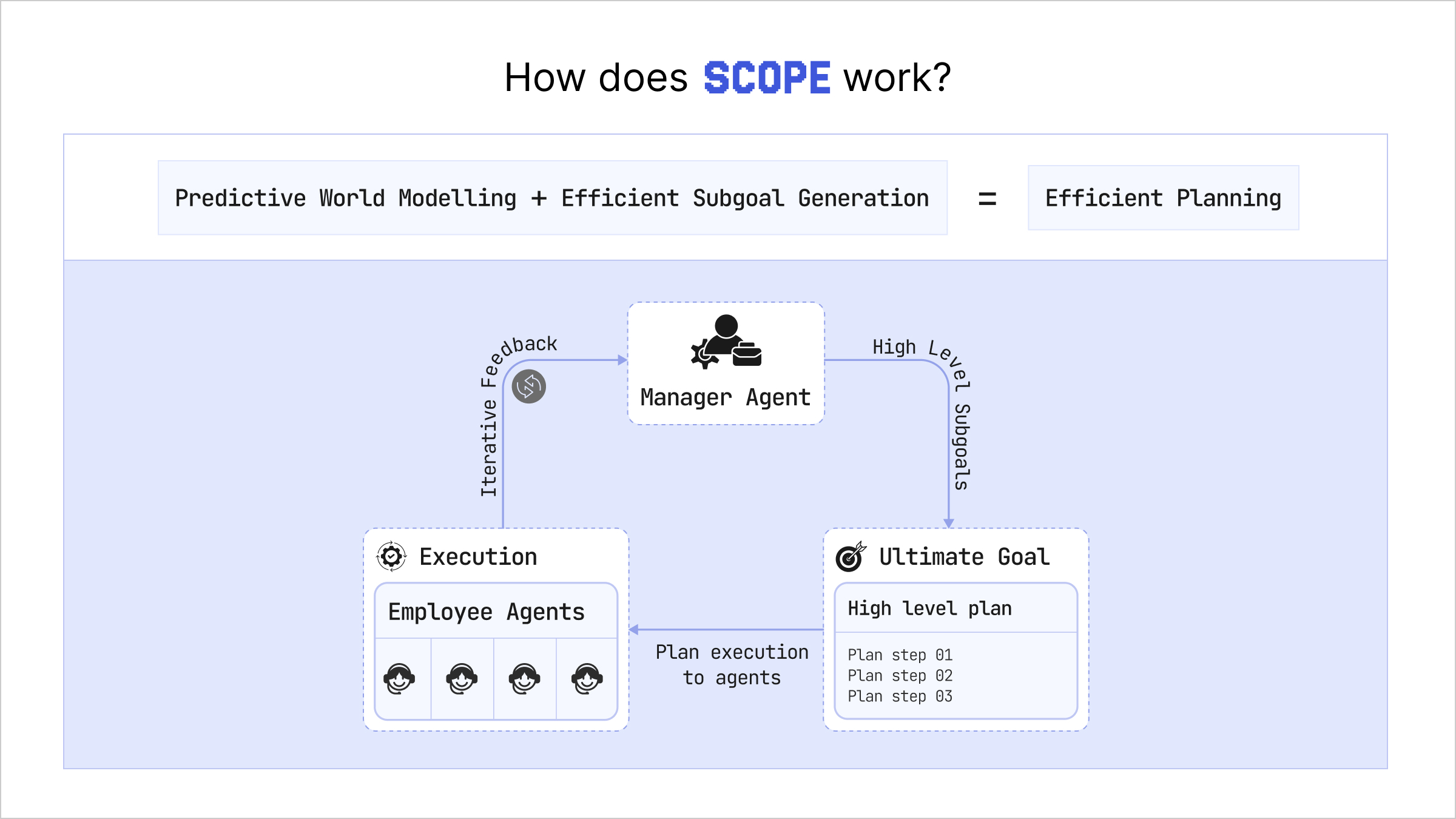

How It Works

SCOPE's approach is conceptually simple but powerful. We use an LLM as a one-time teacher rather than a constantly-consulted oracle. The process unfolds in four distinct stages that together create a system capable of outperforming continuous LLM querying.

The first stage is one-time knowledge extraction. You gather (sample) roughly fifty example expert trajectories from your domain and provide them to an LLM. Rather than asking the LLM to solve planning problems directly, you ask it to generate Python functions that systematically decompose any trajectory into subgoals. The LLM analyzes the patterns in your demonstrations and produces two functions: one that breaks trajectories into subtrajectories with associated subgoals, and another that checks whether a given subgoal has been achieved in a particular state. This happens once during system initialization and costs just pennies in API fees. The beauty is that these functions are general. They can decompose any trajectory in your domain, not just the fifty examples the LLM saw.

The second stage applies these decomposition functions to your full dataset of demonstration trajectories. In our experiments, we had 500,000 trajectories that we automatically decomposed using the LLM-generated functions. SCOPE trains two small neural components: a manager agent that predicts subgoals and an employee agent that executes them. To train these components, the LLM-generated decomposition gives us two supervised datasets: one pairing states, actions, subgoals, and instructions for training the employee agent, and another pairing initial states, subgoals, ultimate goals, and instructions for training the manager agent. The key insight here is that while the LLM only saw fifty examples, its generated functions can process hundreds of thousands of trajectories without any additional LLM queries.

The third stage involves training the two specialized neural networks through imitation learning followed by reinforcement learning (RL). The employee agent learns to accomplish individual subgoals. During pretraining, it learns to mimic the expert actions taken in the demonstration trajectories for each subgoal. During RL fine-tuning, it practices in a simulated world model, learning more efficient ways to achieve subgoals and reaching 91% subgoal completion rate. The manager agent learns to propose sequences of subgoals. During pretraining, it learns to reproduce the LLM's subgoal decompositions. During RL fine-tuning, it learns which subgoals the employee can actually achieve, adapting its proposals to the employee's capabilities. This co-adaptation between manager and employee is crucial. The manager learns to work around the employee's imperfections, finding achievable paths to the goal.

The fourth stage is deployment. Once trained, the manager and employee agents work together in a hierarchical loop. The manager examines the current state and ultimate goal, then proposes the next subgoal. The employee takes control and executes actions to achieve that subgoal, either succeeding within a step limit or timing out and returning control. The manager then proposes the next subgoal, and this continues until the ultimate goal is reached. The entire system runs on a single GPU with no API calls, completing tasks in roughly three seconds.

The Results

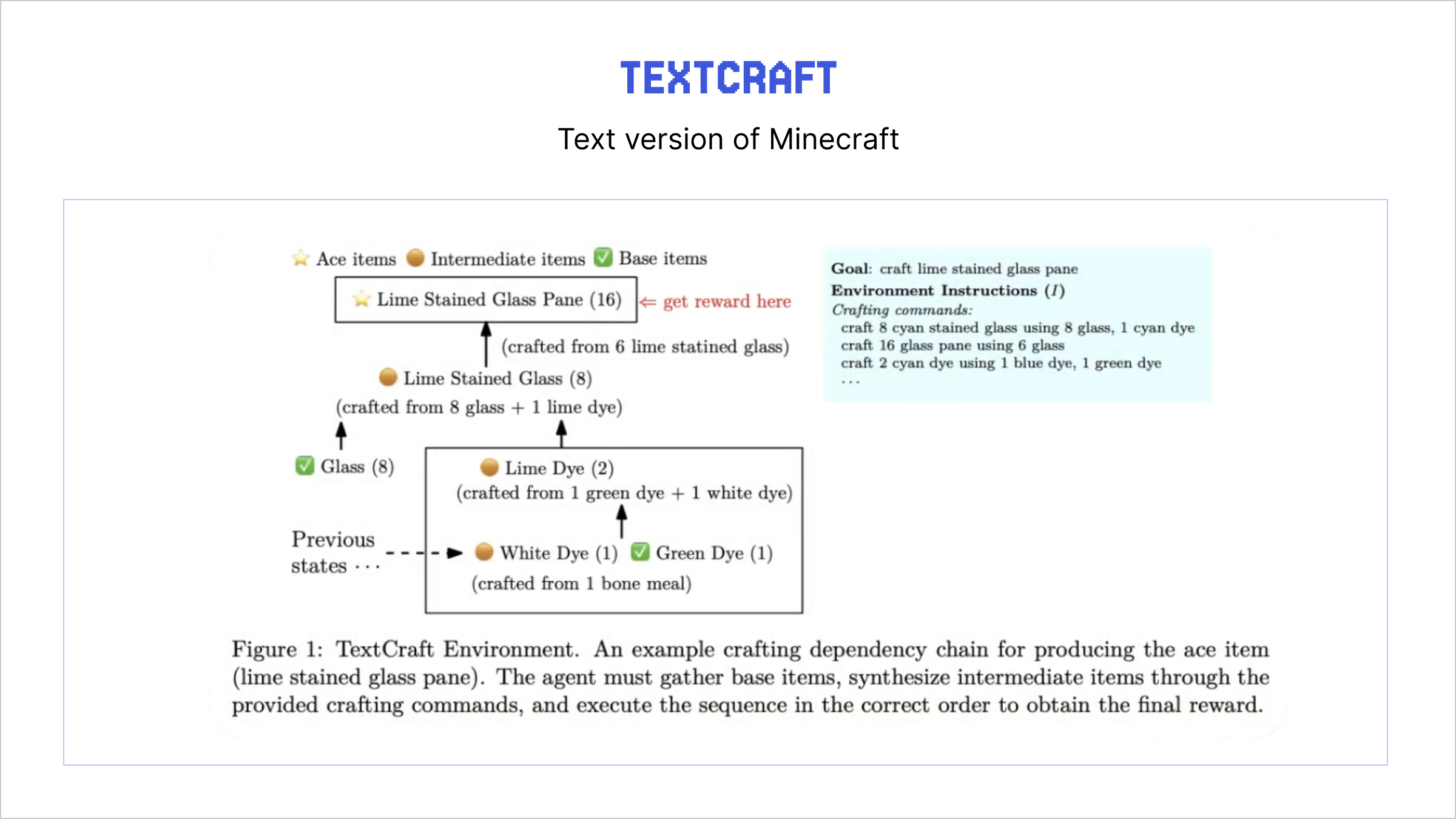

We evaluated SCOPE on TextCraft, a text-based planning environment inspired by Minecraft. TextCraft requires agents to perform long-horizon compositional reasoning, which means gathering base materials, crafting intermediate items in the correct order, and producing final target items. The environment is deliberately designed to test planning ability, as the agent must execute precise action sequences to succeed.

Figure 2: Description of how a task is completed in TextCraft

ADaPT, our baseline system, uses GPT-3.5 as its backend, accessed via the OpenAI API. It achieves a 52% success rate, meaning it successfully crafts the target item in 52% of test episodes. Each episode takes about 164 seconds (almost three minutes) under ideal network conditions. Under the hood, GPT-3.5 has 175B parameters and requires continuous cloud connectivity.

Figure 3: Comparison of GPT 3.5 vs Scope on how fast each episode runs on TextCraft

SCOPE achieves a 56% success rate using our one-time LLM extraction approach. Each episode completes in an average of 3.0 seconds on a single NVIDIA A10 GPU. The complete system uses 11.04 million parameters and runs entirely locally with no network dependency. The 8% relative improvement in success rate might seem modest, but it demonstrates that one-time LLM guidance can actually outperform continuous querying when combined with proper learning mechanisms.

Figure 4: Comparison of GPT 4o vs Scope regarding size of the model on TextCraft

The efficiency gains are dramatic. SCOPE runs 55 times faster than ADaPT, transforming what was a nearly three-minute wait into a three-second interaction. The model is 160,000 smaller, allowing deployment on modest hardware rather than requiring access to massive cloud infrastructure. After the one-time initialization cost, there are no ongoing API fees, just the electricity to run your local GPU.

To understand how general this picture is, we didn’t stop at GPT-3.5, even though it remains our default ADaPT configuration for the subsequent analyses. We also ran ADaPT with a broader lineup of modern LLM backends, including GPT-4o and GPT-4o mini (OpenAI), Claude-3 Haiku (Anthropic), Mistral Small 3 (Mistral), and DeepSeek-R1-Distill-Qwen-32B (DeepSeek). These models span a wide range of sizes, from compact “small” models to extremely large ones, and include both closed-source APIs and open-weight models that you can deploy on your own machines. As expected, stronger backends like GPT-4o can push ADaPT’s success rate higher. What is more interesting is that SCOPE remains in the same performance ballpark as the best of these systems while being orders of magnitude smaller and fully local, and it even outperforms several of the modern backends in our evaluation.

Figure 5: Comparison of Frontier LLM models vs Scope for success rate on TextCraft

The Surprising Finding

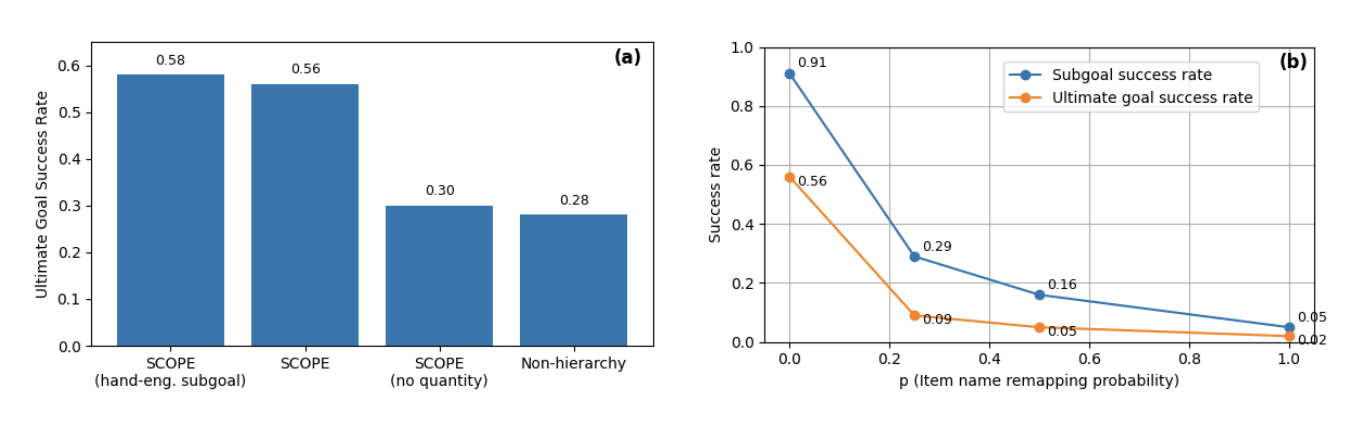

One of our most counterintuitive discoveries is that the LLM-generated subgoals are objectively suboptimal, yet the system still achieves excellent performance. We ran an ablation study comparing three approaches to understand how subgoal quality affects final results.

We created hand-engineered subgoals by carefully analyzing the task structure and defining clear milestone states. For a task like crafting a birch trapdoor, the hand-engineered approach produces complete intermediate states: first having four birch planks and one birch log, then having eight birch planks ready for crafting, and finally the completed trapdoor with remaining materials. Each subgoal is interpretable and captures a meaningful checkpoint in the crafting process. This approach achieves a 58% success rate.

The LLM-generated subgoals are far less interpretable. For that same birch trapdoor task, the LLM proposes having one birch log, then six birch planks (why six specifically?), then one birch trapdoor. These subgoals are cryptic, specifying partial states without the full context that makes hand-engineered subgoals clear. Yet this approach achieves a 56% success rate, only two percentage points behind the hand-engineered version.

Figure 6: Impact of subgoal quality on agent performance

For comparison, we also tested a non-hierarchical baseline that uses the same architecture and training procedure as the employee agent but tries to plan directly to the ultimate goal without any subgoals. This flat approach achieves only 28% success rate, demonstrating that the hierarchical structure itself is critical.

The lesson is liberating for practical deployment. You don't need domain experts carefully crafting perfect subgoal hierarchies. You can accept that an LLM doing one-time decomposition will produce suboptimal, less interpretable subgoals, and trust the learning process to work with that imperfect structure. The 28% to 56% improvement from having LLM subgoals versus no subgoals is far more important than the 56% to 58% gap between LLM and hand-engineered subgoals.

Manager Agent Accommodates Employee Imperfections

Figure 7: High level architecture of how SCOPE works

A key mechanism enabling SCOPE's success is the manager's ability to adapt to the employee's limitations through RL. We ran an ablation study that illuminates this dynamic by removing the manager's RL fine-tuning stage.

In this variant, we gave the employee agent a fixed sequence of achievable subgoals extracted from successful validation trajectories. We deliberately chose hand-engineered subgoals for maximum interpretability. These are clear milestones that should logically lead to goal completion. In principle, a perfect employee trained on these subgoals could simply execute them in sequence and successfully craft the target item every time.

The results reveal the importance of adaptation. Without a manager that can adjust the plan, this variant achieves only 24% success rate despite having access to known-good subgoal sequences. When the employee fails to complete a subgoal in the predetermined sequence (which happens frequently due to the employee's imperfect training), the system cannot recover. It's locked into a fixed plan with no flexibility.

With manager RL fine-tuning enabled, the success rate jumps from 24% to 56%. The manager learns to propose alternative subgoals when the employee struggles. If a proposed subgoal isn't achieved because the employee lacks the necessary skills, that proposal receives no positive feedback during training. Over time, the manager discovers easier, more achievable subgoals that the employee can reliably complete. The manager essentially learns a joint strategy that accounts for both the task requirements and the employee's actual capabilities.

We observed this adaptation process during training. The validation success rate for the manager agent increases steadily throughout RL fine-tuning, climbing from initial performance around 40% up toward 56% as the manager learns which subgoals work well with the trained employee. This progressive improvement reflects the manager discovering better strategies through trial and error in the simulated world model.

Stronger Employee Leads to Higher Success Rates

While manager adaptation is crucial, we also wanted to understand how employee capability affects overall performance. We analyzed the relationship between subgoal success rate and ultimate goal success rate using checkpoints from different stages of employee training.

The pattern is clear and striking. As the employee's ability to complete individual subgoals improves, the overall success rate increases superlinearly. This makes intuitive sense when you consider that subgoals must typically be achieved in sequence. If the employee completes subgoals with 90% reliability and a task requires three subgoals, the overall success is approximately 0.90 cubed, or about 73%. Even a small improvement in per-subgoal reliability compounds across multiple steps.

In our final system, the employee achieves 91% subgoal completion rate on the validation set after RL fine-tuning. When this strong employee is paired with a well-adapted manager that proposes achievable subgoals, the overall goal completion rate reaches 56%. The compounding effect of high subgoal reliability across multiple sequential subgoals drives strong ultimate performance.

This finding has practical implications for system design. Investment in improving the employee agent pays dividends throughout the system. A stronger employee not only completes more subgoals directly but also gives the manager more options to work with. The manager can propose more ambitious subgoals when confident the employee can handle them, leading to more efficient plans overall.

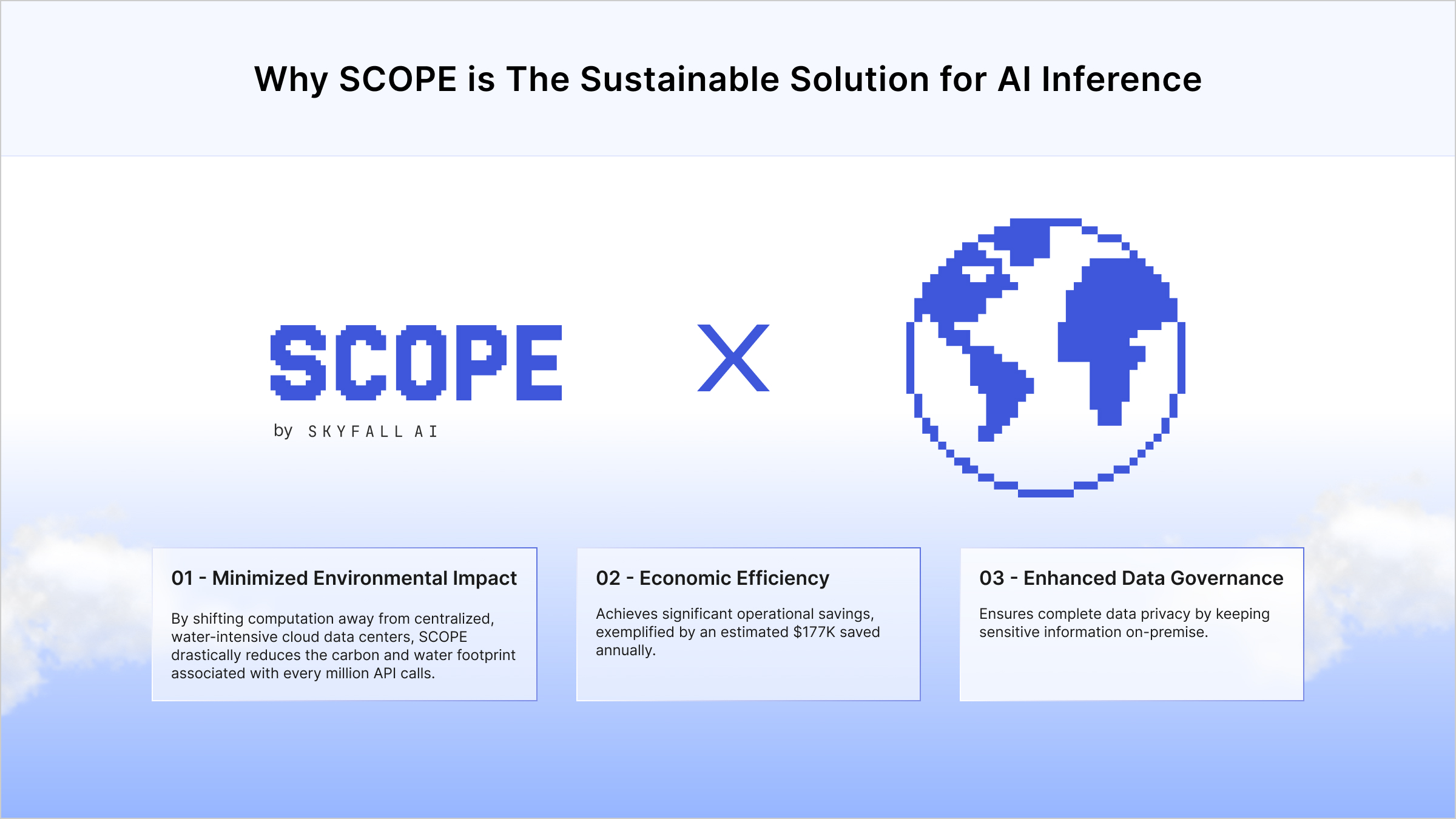

Why This Matters?

The economics of LLM-based planning agents simply don't work at scale. If you're deploying thousand customer service agents, each handling a hundred tasks per day with five LLM queries per task at a conservative dollar per thousand tokens, you're burning through five hundred dollars daily. That's over $182,000 annually, and that's just for the planning queries, not the actual execution or any other API calls your system needs.

The return on investment with SCOPE tells a completely different story. After a one-time setup cost of roughly ten dollars for the initial LLM extraction, your ongoing costs drop to just GPU electricity (because SCOPE performs all inference locally on a single GPU), maybe five thousand dollars per year for comparable deployment. Even a highly conservative estimate shows that you're saving $177,500 annually while actually getting better performance. Beyond the cost savings, you eliminate network dependency entirely, which means your agents can run anywhere without worrying about connectivity or latency. You gain full control over the models, allowing you to fine-tune them to your specific domain, learn from deployment experience, and continuously improve based on your unique requirements.

The deployment flexibility alone changes what's possible. Instead of being constrained by API rate limits, you can scale horizontally by deploying as many instances as you have GPUs. Instead of suffering through 164 seconds of latency per task, you get three-second response times that enable true real-time interaction. Instead of sending sensitive data to cloud APIs, you can keep everything on-premises for privacy and compliance.

Furthermore, a system requiring millions of LLM queries per day is not just costly, it carries substantial CO₂ emissions from datacenter-scale compute. SCOPE’s local, lightweight inference removes this environmental overhead.

Figure 8: Why is SCOPE sustainable for AI Inference

What's Next?

We believe in presenting honest science with clear limitations alongside positive results. SCOPE has demonstrated strong performance on TextCraft, but several important questions remain open for future investigation.

Our current validation covers only TextCraft, a relatively simple text-based environment with deterministic transitions and discrete actions. The natural next step is scaling to more complex domains. Full Minecraft with visual observations, continuous action spaces, and stochastic dynamics would test whether SCOPE's approach generalizes beyond the simplified setting. Real robotic manipulation tasks with sensor noise, actuation uncertainty, and safety constraints would reveal whether the method works in physical systems. Multi-agent scenarios requiring coordination and communication would explore whether hierarchical structure helps in social settings.

There's also headroom for improving the subgoal extraction process itself. Hand-engineered subgoals achieve 58% compared to our LLM-generated 56%, suggesting the decomposition quality could be better. We could explore more sophisticated prompting strategies that give the LLM more context about the task structure. We might allow limited environment interaction during the extraction phase so the LLM can test its decomposition ideas. Iterative refinement procedures could progressively improve the decomposition functions based on how well they work in practice.

The world model dependency deserves attention for more complex environments. TextCraft's deterministic transitions made world modeling straightforward. We learned only action validity and implemented state transitions with simple rules. Environments with stochastic dynamics, partial observability, continuous states, or complex physics will require more sophisticated world modeling approaches. Recent advances in video prediction, neural physics engines, and uncertainty quantification might help extend SCOPE to these challenging domains.

We're also curious about online adaptation and continual learning. Can SCOPE keep improving during deployment as it encounters new scenarios? How should the system handle distribution shift when deployment conditions differ from training? Could active learning help the agents identify and focus on challenging edge cases? These questions point toward systems that not only deploy efficiently but continue learning throughout their operational lifetime.

Finally, transfer learning across domains remains an exciting possibility. Does the planning structure learned in TextCraft transfer to other crafting games? Can subgoal decompositions learned in simulation transfer to real robots? Could we build a library of reusable decomposition functions that work across families of related tasks? Positive answers would dramatically reduce the data and computation needed to deploy SCOPE in new domains.

Conclusion

SCOPE demonstrates that efficient AI planning is not only possible but can actually outperform much larger systems. By treating LLMs as one-time teachers that extract structural knowledge rather than runtime oracles that must be constantly consulted, we achieve better performance with dramatically better efficiency.

The results speak clearly. SCOPE achieves a 56% success rate compared to ADaPT's 52%, an 8% improvement which demonstrates that one-time extraction can outperform continuous querying. SCOPE runs 55 times faster than ADaPT at 3 seconds versus 164 seconds per task, making real-time applications practical. SCOPE uses 15,000 times fewer parameters at 11 million versus 175 billion, enabling deployment on modest hardware.

For researchers, SCOPE opens questions about knowledge transfer from large models to small ones, the role of hierarchical structure in enabling efficient learning, and the surprising effectiveness of imperfect guidance combined with adaptation. For practitioners, SCOPE offers a concrete path to deploying planning agents at scale without breaking the bank or compromising performance.

The era of efficient AI planning has arrived. The question is no longer whether we can build capable planning agents, but whether we can deploy them practically at scale. SCOPE is the first step to show that we can.

Link to the paper is here.