Image credit: ©besjunior. stock.adobe.com

Ice Formation is Not a Singular Phenomenon

Lake and river ice is an amazing, dangerous, and wonderful thing. My home office overlooks the Duluth harbor with a view out to Lake Superior on one side and the St. Louis River on the other. This winter when I take breaks from working at my desk, I look out at the forming, drifting, breaking, and piling ice and see more than simply ice. The formation of ice on lakes is important due to its influence on lake biology, shore structure, navigation, and recreation. It is also a source of economic cost due to the shore and infrastructure damage it can cause.

Ice is all around us in winter in the temperate zone, but I doubt many of us consider how it is formed. We talk about ice-up of lakes as if it is a singular thing. In reality though, it happens in many different ways and may be very different in the same lake in different years. The cyclic nature or phenology of ice-up makes a huge difference in the quality of the ice and changes the under-ice environment as well as the safety of lake ice cover.

What Determines How Ice Forms?

The two most important factors in determining how ice forms are temperature and turbulence (Michel and Ramseier 1971). Temperature is under the control of climate and turbulence is affected by the size of the water body and the materials that make up the bottom and sides of that water body. Turbulence in streams is driven by the speed of water and by the kinds of materials that form the stream’s channel. Bumpy materials result in more turbulence. Turbulence can also be high in large lakes when the wind can blow over the water surface for large distances and creates waves and currents.

Calm Water Ice Formation and a Quirk of Density

Under calm conditions, ice freezes on lakes very similarly to how it freezes in an ice-cube tray. Lake ice freezes first at the surface starting at the edges or shoreline for two reasons.

Water near the shore is typically shallower and contains less heat than deeper water so it can reach the freezing point faster than deeper water. But curiously, as water cools from 40 degrees F (4 degrees C) to the freezing point it becomes denser or said another way, its weight per unit of volume increases. So, you might ask, if denser water sinks, why does the ice form on top?

Quirk alert: As water approaches its freezing point (32 degrees F / 0 degrees C) it becomes less dense than the water around it and rises to the top of the surrounding water.

Primary Ice and Fast Ice

Image credit: John A. Downing/Minnesota Sea Grant.

In a calm lake or pond, the first ice or “primary ice” is quite clear and crystalline and is made up of hexagonal plates, needles, or sheath-like structures with large crystals oriented up-and-down.

Image credit: John A. Downing/Minnesota Sea Grant.

Image credit: Titus Seilheimer/Wisconsin Sea Grant

When the ice cover expands from the shore to the entire lake surface, it’s called "fast ice" because it is held fast by the shore. When conditions are cold and calm, this is the ice-up condition that can create excellent skating at the beginning of the season as long as snow does not accumulate and warm weather does not cause surface melting.

Ice Molecules and Clarity

Image credit: ©artegorov3@gmail. stock.adobe.com

Water molecules are composed of two hydrogen atoms that are each attached to the same oxygen molecule in a triangular formation. In liquid water, these molecules arrange themselves randomly. In ice, the molecules align themselves in a regular lattice pattern and are more spread out, which results in ice being less dense than water. Because the crystal lattice allows a lot of light to pass through, the under-ice environment is surprisingly bright. Aquatic algae and plants can grow under lake ice.

Rough Water Ice Formation and Frazil

Image credit: John A. Downing/Minnesota Sea Grant.

Under turbulent conditions, ice freezes in a less orderly and transparent way than in calm water conditions. In turbulent conditions, initial ice formation is due to the formation of what is called frazil ice or fine ice crystals suspended in the water. Frazil ice is usually smaller than one inch in length, and is shaped like sharp-pointed objects or small disks (Pounder 1965).

Frazil forms in the top inch or so of the moving surface water because the water there is colder than the water below - the same reason as clear ice forms toward the surface.

Frazil clumps together quite easily and forms a sort of slush at the water’s surface and can pile up and accumulate when pushed by wind or currents. When the slush clumps together it forms “sludge ice” (Armstrong and Roberts 1956). Sludge ice decreases surface turbulence because it is viscous and when it freezes it can create a solid ice cover at the water’s surface. Although clumps or rafts of frazil and sludge can accumulate in open water creating ice floes, the action of wind and current normally make this ice grow from the shore outward.

Because the frazil crystals are small and oriented in a variety of directions and the freezing of frazil incorporates gas bubbles and other materials, the primary ice that forms under turbulent conditions is usually less transparent and less smooth than ice formed under calm conditions. Again, this process continues until the surface of the water is covered with fast ice that is attached to the shore.

Floating your Truck on a Lake

Image credit: M. Thoms/Minnesota Sea Grant

The way ice forms is important for safety and ecology. The “white ice” formed from snow, sludge or under turbulent conditions is much weaker and breaks more easily than the “black ice” formed under calm conditions or at the interface between ice and water.

Weight, like my pickup truck, when applied to ice is supported by the water underneath it and not by the ice (Ashton 2010). This way of thinking about ice stopped me cold for a moment.

You may remember Archimedes’ principle from high-school physics. According to the legend, when Archimedes was sitting in a bathtub, he noticed that the water level rose by an amount equal to the mass of his body. From that observation he concluded for an object to be buoyant in water it must displace enough water to be equal to the mass of the object.

In order for ice to float my pickup truck that ice must deform or bend downward to displace an amount of water equal in mass to my pickup truck. If the ice is not stretchy or strong enough to deform and spread the mass of my truck out over a large enough area, the ice will crack and fail. Water will flood the crack and my truck will sink just like a boat with a hole in it. Ice that has formed under turbulent conditions, which is often white ice, is weaker than ”black ice” because it is made of tiny size of crystals (Cherepanov 1974) that will break easily. Additionally, white ice lets less sunlight through it than ”black ice” which means the environment beneath white ice will be darker and less primary production will occur to renew the oxygen under it.

Ice is a Process

Anyone who has watched ice form in the early winter knows that the process can go on for quite some time and is often discontinuous. As weather gets warmer and cooler, ice breaks apart and is pushed back together. Drifting ice is called “pack ice” and is composed of sheets of floating ice called floes that are separated by water. When floes are pushed together so when one floe moves on top of another this is called “rafting.” When sheets of regular, flat, lake-ice (level ice) are broken and haphazardly pile up, this is called “hummocked ice.”

Image credit: M. Thoms/Minnesota Sea Grant

Hummocked ice happens frequently along shores with wind exposure and can cause shore soils and material to be pushed inland. This ice-push, which is also called ice ride-up, ice surge, or ice ramping, can be quite violent and can cause severe damage to shore infrastructure, especially when ice breaks up under high wind stress.

What’s Happening Down Below?

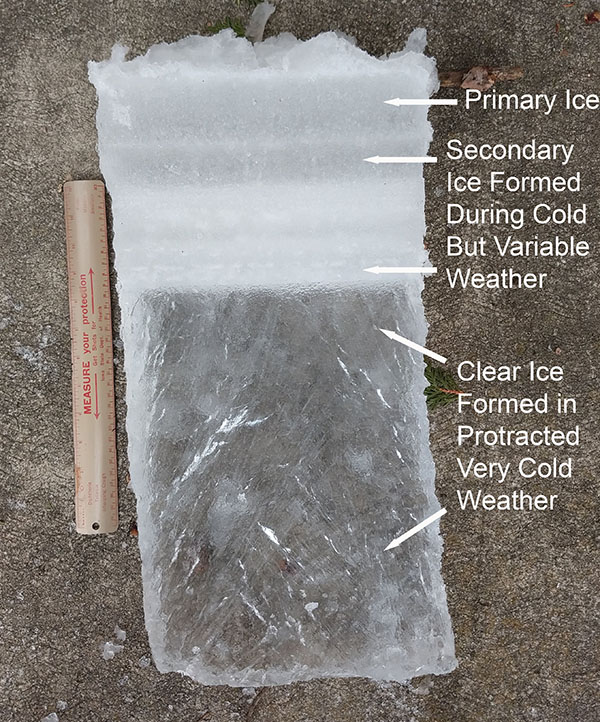

Secondary ice is formed at the bottom of the surface ice by the clumping of frazil, the consolidation, freezing, and crystallization that results when heat moves up through the water toward the surface. This often soupy ice layer can be created from a slurry of frazil or simply by the crystallization of new ice below the primary layer. Another layer of ice is “superimposed ice” (Michel and Ramseier 1971) that forms over the top of primary ice. Most of us have sunk through superimposed ice after the ice has been through a few freeze-thaw cycles. Superimposed ice forms when water has flowed out onto the surface of the primary ice or onto the snow covering primary ice. The water can be from runoff from shore, shallow groundwater seepage from above the ice surface, rainfall, stream inflow, or surface snow and ice melted from the warm sun. Although superimposed ice freezes at the top, it sometimes leaves a considerable slush and water layer beneath it and above the primary ice.

Why Ice Floats and Bergy Bits

Image credit: ©alonesdj. stock.adobe.com

The principle explaining why ice floats is the same for what we erroneously call icebergs on Lake Superior and for the ice in your beverage. Ice floats because it is 9% less dense than liquid water of nearly the same temperature. It’s that 9% of the ice that’s floating above the water level of the lake or your drink. To be classified as a true iceberg, the height of the ice must be greater than 16 feet above the water surface, the thickness must be 98 to 174 feet, and the ice must cover an area of at least 5,382 square feet. What we see on Lake Superior are rarely the size of a true iceberg and are more likely to be what are called “bergy bits” or “growlers.”

Bergy bits are pieces of ice that are generally greater than 3 feet in height, less than 16 feet above the water level, and 1,076 to 3,220 square feet in area. A bergy bit protruding just 3 feet above the water would have about nine times as much ice under the water as above it. A growler is a piece of ice roughly the size of a truck or grand piano that is low enough to the water that waves can wash over it.

When is Ice Safe for People, Trucks or Horses?

After ice-up there is usually a time period when ice cover looks good but is highly unsafe. People may also mistakenly assume ice thickness to be fairly uniform across a lake, but this is far from true (Brown and Duguay 2011). Bengtsson (1986) measured ice thickness in many places across several lakes and found that ice thickness could vary by more than 50%, especially when stream inflows or outflows are within a mile or so. Variations in ice thickness result from the way in which ice is formed and what happens to it over the winter.

The rate at which ice thickens depends on the temperature at the bottom of the ice where it meets the underlying water and the thickness of the ice. When ice is thin, heat from the water below that ice can escape to the air relatively quickly, which cools the water and allows ice to form. When ice is thick, the heat of the water escapes more slowly into the air, which means the water stays warmer longer and it takes longer for thick ice to become thicker.

In-shore ice forms first so may be thickest once a lake is completely covered in ice. Bays and harbors that freeze rapidly in the early winter may also initially be thickest. As winter proceeds, ice thickness can tend to even out across a lake (Bengtsson 1986). For example, when snow drifts onto thinner ice, it can slow the thickening of that ice through insulation. While the thicker ice continues to slowly grow thicker, the now-insulated thinner ice is also growing thicker more slowly.

Later in winter, in- and near-shore ice may be thinnest because of the inflow of groundwater and the activities of winter-active mammals. Black or crystalline ice tends to grow on the bottom of the ice cover whereas white ice grows on top of the ice due to the freezing of snow (Bengtsson 1986).

Caution is always advisable when working or recreating on ice. When my grandmother was a child, their family lost two teams of horses through the ice on the lake where I grew up. I know exactly where they went in because, due to groundwater or other currents, that area which is about 100 feet from shore still always has thin ice.