FREEDOM (while hoping my friends stay safe)

January 11th, 2026

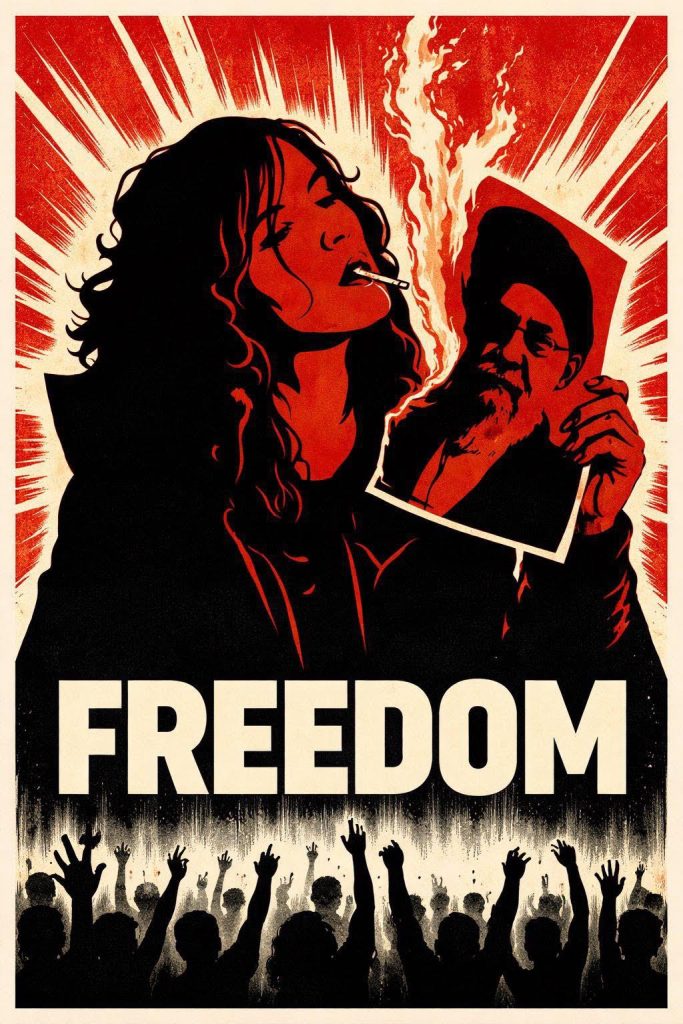

This deserves to become one of the iconic images of human history, alongside the Tank Man of Tiananmen Square and so forth.

Here’s Sharifi Zarchi, a computer engineering professor at Sharif University in Tehran, posting on Twitter/X: “Ali Khamenei is not my leader.”

Do you understand the balls of steel this takes? If Professor Zarchi can do this—if hundreds of thousands of young Iranians can take to the streets even while the IRGC and the Basij fire live rounds at them—then I can certainly handle people yelling me on this blog!

I’m in awe of the Iranian people’s courage, and hope I’d have similar courage in their shoes.

I was also enraged this week at the failure of much of the rest of the world to help, to express solidarity, or even to pay much attention to the Iranian’s people plight (though maybe that’s finally changing this weekend).

I’ve actually been working on a CS project with a student in Tehran. Because of the Internet blackout, I haven’t heard from him in days. I pray that he’s safe. I pray that all my friends and colleagues in Iran, and their family members, stay safe and stay strong.

If any Iranian Shtetl-Optimized reader manages to get onto the Internet, and would like to share an update—anonymously if desired, of course—we’d all be obliged.

May the Iranian people be free from tyranny soon.

Posted in The Fate of Humanity | 30 Comments »

The Goodness Cluster

January 7th, 2026

The blog-commenters come at me one by one, a seemingly infinite supply of them, like masked henchmen in an action movie throwing karate chops at Jackie Chan.

“Seriously Scott, do better,” says each henchman when his turn comes, ignoring all the ones before him who said the same. “If you’d have supported American-imposed regime change in Venezuela, like just installing María Machado as the president, then surely you must also support Trump’s cockamamie plan to invade Greenland! For that matter, you logically must also support Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, and China’s probable future invasion of Taiwan!”

“No,” I reply to each henchman, “you’re operating on a wildly mistaken model of me. For starters, I’ve just consistently honored the actual democratic choices of the Venezuelans, the Greenlanders, the Ukrainians, and the Taiwanese, regardless of coalitions and power. Those choices are, respectively, to be rid of Maduro, to stay part of Denmark, and to be left alone by Russia and China—in all four cases, as it happens, the choices most consistent with liberalism, common sense, and what nearly any 5-year-old would say was right and good.”

“My preference,” I continue, “is simply that the more pro-Enlightenment, pluralist, liberal-democratic side triumph, and that the more repressive, authoritarian side feel the sting of defeat—always, in every conflict, in every corner of the earth. Sure, if authoritarians win an election fair and square, I might clench my teeth and watch them take power, for the sake of the long-term survival of the ideals those authoritarians seek to destroy. But if authoritarians lose an election and then arrogate power anyway, what’s there even to feel torn about? So, you can correctly predict my reaction to countless international events by predicting this. It’s like predicting what Tit-for-Tat will do on a given move in the Iterated Prisoners’ Dilemma.”

“Even more broadly,” I say, “my rule is simply that I’m in favor of good things, and against bad things. I’m in favor of truth, and against falsehood. And if anyone says to me: because you supported this country when it did good thing X, you must also support it when does evil thing Y? (Either as a reductio ad absurdum, or because the person actually wants evil thing Y?) Or if they say: because you agreed with this person when she said this true thing, you must also endorse this false thing she said? I reply: good over evil and truth over lies in every instance—if need be, down to the individual subatomic particles of morality and logic.”

The henchmen snarl, “so now it’s laid bare! Now everyone can see just how naive and simplistic Aaronson’s so-called ‘political philosophy’ really is! Do us all a favor, Scott, and stick to quantum physics! Stick to computer science! Do you not know that philosophers and political scientists have filled libraries debating these weighty matters? Are you an act-utilitarian? A Kantian? A neocon or neoliberal? An America-First interventionist? Pick some package of values, then answer to us for all the commitments that come with that package!”

I say: “No, I don’t subcontract out my soul to any package of values that I can define via any succinct rule. Instead, given any moral dilemma, I simply query my internal Morality Oracle and follow whatever it tells me to do, unless of course my weakness prevents me. Some would simply call the ‘Morality Oracle’ my conscience. But others would hold that, to whatever extent people’s consciences have given similar answers across vast gulfs of time and space and culture, it’s because they tapped into an underlying logic that humans haven’t fully explained, but that they no more invented than the rules of arithmetic. The world’s prophets and sages have tried again and again over the millennia to articulate that logic, with varying admixtures of error and self-interest and culture-dependent cruft. But just like with math and science, the clearest available statements seem to me to have gotten clearer over time.”

The Jackie Chan henchman smirks at this. “So basically, you know the right answers to moral questions because of a magical, private Morality Oracle—like, you know, the burning bush, or Mount Sinai? And yet you dare to call yourself a scientific rationalist, a foe of obscurantism and myticism? Do you have any idea how pathetic this all sounds, as an attempted moral theory?”

“But I’m not pretending to articulate a moral theory,” I reply. “I’m merely describing what I do. I mean, I can gesture toward moral theories and ideas that capture more of my conscience’s judgments than others, like liberalism, the Enlightenment, the Golden Rule, or utilitarianism. But if a rule ever appears to disagree with the verdict of my conscience—if someone says, oh, you like utilitarianism, so you must value the lives of these trillion amoebas above this one human child’s, even torture and kill the child to save the amoebas—I will always go with my conscience and damn the rule.”

“So the meaning of goodness is just ‘whatever seems good to you’?” asks the henchman, between swings of his nunchuk. “Do you not see how tautological your criterion is, how worthless?”

“It might be tautological, but I find it far from worthless!” I offer. “If nothing else, my Oracle lets me assess the morality of people, philosophies, institutions, and movements, by simply asking to what extent their words and deeds seem guided by the same Oracle, or one that’s close enough! And if I find a cluster of millions of people whose consciences agree with mine and each others’ in 95% of cases, then I can point to that cluster, and say, here. This cluster’s collective moral judgment is close to what I mean by goodness. Which is probably the best we can do with countless questions of philosophy.”

“Just like, in the famous Wittgenstein riff, we define ‘game’ not by giving an if-and-only-if, but by starting with poker, basketball, Monopoly, and other paradigm-cases and then counting things as ‘games’ to whatever extent they’re similar—so too we can define ‘morality’ by starting with a cluster of Benjamin Franklin, Frederick Douglass, MLK, Vasily Arkhipov, Alan Turing, Katalin Karikó, those who hid Jews during the Holocaust, those who sit in Chinese or Russian or Iranian or Venezuelan torture-prisons for advocating democracy, etc, and then working outward from those paradigm-cases, and whenever in doubt, by seeking reflective equilibrium between that cluster and our own consciences. At any rate, that’s what I do, and it’s what I’ll continue doing even if half the world sneers at me for it, because I don’t know a better approach.”

Applications to the AI alignment problem are left as exercises for the reader.

Announcement: I’m currently on my way to Seattle, to speak in the CS department at the University of Washington—a place that I love but haven’t visited, I don’t think, since 2011 (!). If you’re around, come say hi. Meanwhile, feel free to karate-chop this post all you want in the comment section, but I’ll probably be slow in replying!

Posted in Metaphysical Spouting, The Fate of Humanity | 76 Comments »

Venezuela through the lens of good and evil

January 4th, 2026

I woke up yesterday morning happy and relieved that the Venezuelan people were finally free of their brutal dictator.

I ended the day angry and depressed that Trump, as it turns out, does not seek to turn over Venezuela to María Corina Machado and her inspiring democracy movement—the pro-Western, Nobel-Peace-Prize-winning, slam-dunk obvious, already electorally-confirmed choice of the Venezuelan people—but instead seeks to cut a deal with the remnants of Maduro’s regime to run Venezuela as a US-controlled petrostate.

I confess that I have trouble understanding people who don’t have either of these two reactions.

On one side of me, of course, are the sneering MAGA bullies who declare that might makes right, that the strong do what they can while the weak suffer what they must, and that the US should rule Venezuela for the same reason why Russia should rule Ukraine and China should rule Taiwan: namely, because the small countries have the misfortune of being in the large ones’ “spheres of influence.”

But on my other side are those who squeal that toppling a dictator, however odious, is against the rules, because right is whatever “international law” declares it to be—i.e., the “international law” that’s now been degraded by ideologues to the point of meaninglessness, the “international law” that typically sides with whichever terrorists and murderers have the floor of the UN General Assembly and that condemns persecuted minorities for defending themselves.

The trouble is, any given framework of law needs to do at least one of three things to impose its will on me:

- Compel my obedience, by credibly threatening punishment if I defy it.

- Win the assent of my conscience, by the force of its moral example.

- Buy my consent through reciprocity: if this framework will defend my family from being murdered, I therefore ought to defend it.

But “international law,” as it exists today, fails spectacularly on all three of these counts. Ergo, as far as I’m concerned, it can take a long walk off a short pier.

Against these two attempted reductions of right to something that it isn’t, I simply say:

Right is right. Good is good. Evil is evil. Good is liberal democracy and the Enlightenment. Evil is authoritarianism and liars and bullies.

Good, in this case, is Maria Machado and the Venezuelans who went to prison, who took to the streets, who monitored every polling station to prove Edmundo González’s victory. Evil is those who oppose them.

But who gets to decide what’s good and what’s evil? Well, if you’re here asking me, then I decide.

But don’t the evildoers believe themselves to be good? Yes, but they’re wrong.

It’s crucial that I’m not appealing here to anything exotic or esoteric. I’m appealing only to the concepts of good and evil that I suspect every reader of this blog had as a child, that they got from fables and Disney movies and Saturday morning cartoons and the like, before some of them went to college and learned that those concepts were naïve and simplistic and only for stupid people.

Look: I regularly appear, to my amusement and chagrin, in Internet lists of the smartest people on earth, alongside Terry Tao and Garry Kasparov and Ed Witten. I did publish my first paper at 15, and finished my PhD in theoretical computer science at 22, and became an MIT professor soon afterward, yada yada.

And for whatever it’s worth, I’m telling you that I think the “naïve, simplistic” concepts of good and evil of post-WWII liberal democracy were fine all along, and not only for stupid people. In my humble opinion. Of course those concepts can be improved upon—indeed, criticism and improvement and self-correction are crucial parts of them—but they’re infinitely better than the realistic alternatives on offer from left and right, including kleptocracy, authoritarianism, and what we’re now calling “the warmth of collectivism.”

And according to these concepts, María Machado and the other Venezuelans who stand with her for democracy are good, if anything is good. Trump, despite all the evil in his heart and in his past, will do something profoundly good if he reverses himself and lets those Venezuelans have what they’ve fought for. He’ll do evil if he doesn’t.

Happy New Year, everyone. May goodness reign over the earth.

Posted in Embarrassing Myself, Rage Against Doofosity, The Fate of Humanity | 111 Comments »

My Christmas gift: telling you about PurpleMind, which brings CS theory to the YouTube masses

December 24th, 2025

Merry Christmas, everyone! Ho3!

Here’s my beloved daughter baking chocolate chip cookies, which she’ll deliver tomorrow morning with our synagogue to firemen, EMTs, and others who need to work on Christmas Day. My role was limited to taste-testing.

While (I hope you’re sitting down for this) the Aaronson-Moshkovitzes are more of a latke/dreidel family, I grew up surrounded by Christmas and am a lifelong enjoyer of the decorations, the songs and movies (well, some of them), the message of universal goodwill, and even gingerbread and fruitcake.

Therefore, as a Christmas gift to my readers, I hereby present what I now regard as one of the great serendipitous “discoveries” in my career, alongside students like Paul Christiano and Ewin Tang who later became superstars.

Ever since I was a pimply teen, I dreamed of becoming the prophet who’d finally bring the glories of theoretical computer science to the masses—who’d do for that systematically under-sung field what Martin Gardner did for math, Carl Sagan for astronomy, Richard Dawkins for evolutionary biology, Douglas Hofstadter for consciousness and Gödel. Now, with my life half over, I’ve done … well, some in that direction, but vastly less than I’d dreamed.

A month ago, I learned that maybe I can rest easier. For a young man named Aaron Gostein is doing the work I wish I’d done—and he’s doing it using tools I don’t have, and so brilliantly that I could barely improve a pixel.

Aaron recently graduated from Carnegie Mellon, majoring in CS. He’s now moved back to Austin, TX, where he grew up, and where of course I now live as well. (Before anyone confuses our names: mine is Scott Aaronson, even though I’ve gotten hundreds of emails over the years calling me “Aaron.”)

Anyway, here in Austin, Aaron is producing a YouTube channel called PurpleMind. In starting this channel, Aaron was directly inspired by Grant Sanderson’s 3Blue1Brown—a math YouTube channel that I’ve also praised to the skies on this blog—but Aaron has chosen to focus on theoretical computer science.

I first encountered Aaron a month ago, when he emailed asking to interview me about … which topic will it be this time, quantum computing and Bitcoin? quantum computing and AI? AI and watermarking? no, diagonalization as a unifying idea in mathematical logic. That got my attention.

So Aaron came to my office and we talked for 45 minutes. I didn’t expect much to come of it, but then Aaron quickly put out this video, in which I have a few unimportant cameos:

After I watched this, I brought Dana and the kids and even my parents to watch it too. The kids, whose attention spans normally leave much to be desired, were sufficiently engaged that they made me pause every 15 seconds to ask questions (“what would go wrong if you diagonalized a list of all whole numbers, where we know there are only ℵ0 of them?” “aren’t there other strategies that would work just as well as going down the diagonal?”).

Seeing this, I sat the kids down to watch more PurpleMind. Here’s the video on the P versus NP problem:

Here’s one on the famous Karatsuba algorithm, which reduced the number of steps needed to multiply two n-digit numbers from ~n2 to only ~n1.585, and thereby helped inaugurate the entire field of algorithms:

Here’s one on RSA encryption:

Here’s one on how computers quickly generate the huge random prime numbers that RSA and other modern encryption methods need:

These are the only ones we’ve watched so far. Each one strikes me as close to perfection. There are many others (for example, on Diffie-Hellman encryption, the Bernstein-Vazirani quantum algorithm, and calculating pi) that I’m guessing will be equally superb.

In my view, what makes these videos so good is their concreteness, achieved without loss of correctness. When, for example, Aaron talks about Gödel mailing a letter to the dying von Neumann posing what we now know as P vs. NP, or any other historical event, he always shows you an animated reconstruction. When he talks about an algorithm, he always shows you his own Python code, and what happened when he ran the code, and then he invites you to experiment with it too.

I might even say that the results singlehandedly justify the existence of YouTube, as the ten righteous men would’ve saved Sodom—with every crystal-clear animation of a CS concept canceling out a thousand unboxing videos or screamingly-narrated Minecraft play-throughs in the eyes of God.

Strangely, the comments below Aaron’s YouTube videos attack him relentlessly for his use of AI to help generate the animations. To me, it seems clear that AI is the only thing that could let one person, with no production budget to speak of, create animations of this quality and quantity. If people want so badly for the artwork to be 100% human-generated, let them volunteer to create it themselves.

Even as I admire the PurpleMind videos, or the 3Blue1Brown videos before them, a small part of me feels melancholic. From now until death, I expect that I’ll have only the same pedagogical tools that I acquired as a young’un: talking; waving my arms around; quizzing the audience; opening the floor to Q&A; cracking jokes; drawing crude diagrams on a blackboard or whiteboard until the chalk or the markers give out; typing English or LaTeX; the occasional PowerPoint graphic that might (if I’m feeling ambitious) fade in and out or fly across the screen.

Today there are vastly better tools, both human and AI, that make it feasible to create spectacular animations for each and every mathematical concept, as if transferring the imagery directly from mind to mind. In the hands of a master explainer like Grant Sanderson or Aaron Gostein, these tools are tractors to my ox-drawn plow. I’ll be unable to compete in the long term.

But then I reflect that at least I can help this new generation of math and CS popularizers, by continuing to feed them raw material. I can do cameos in their YouTube productions. Or if nothing else, I can bring their jewels to my community’s attention, as I’m doing right now.

Peace on Earth, and to all a good night.

Posted in Announcements, Complexity | 37 Comments »

More on whether useful quantum computing is “imminent”

December 21st, 2025

These days, the most common question I get goes something like this:

A decade ago, you told people that scalable quantum computing wasn’t imminent. Now, though, you claim it plausibly is imminent. Why have you reversed yourself??

I appreciated the friend of mine who paraphrased this as follows: “A decade ago you said you were 35. Now you say you’re 45. Explain yourself!”

A couple weeks ago, I was delighted to attend Q2B in Santa Clara, where I gave a keynote talk entitled “Why I Think Quantum Computing Works” (link goes to the PowerPoint slides). This is one of the most optimistic talks I’ve ever given. But mostly that’s just because, uncharacteristically for me, here I gave short shrift to the challenge of broadening the class of problems that achieve huge quantum speedups, and just focused on the experimental milestones achieved over the past year. With every experimental milestone, the little voice in my head that asks “but what if Gil Kalai turned out to be right after all? what if scalable QC wasn’t possible?” grows quieter, until now it can barely be heard.

Going to Q2B was extremely helpful in giving me a sense of the current state of the field. Ryan Babbush gave a superb overview (I couldn’t have improved a word) of the current status of quantum algorithms, while John Preskill’s annual where-we-stand talk was “magisterial” as usual (that’s the word I’ve long used for his talks), making mine look like just a warmup act for his. Meanwhile, Quantinuum took a victory lap, boasting of their recent successes in a way that I considered basically justified.

After returning from Q2B, I then did an hour-long podcast with “The Quantum Bull” on the topic “How Close Are We to Fault-Tolerant Quantum Computing?” You can watch it here:

As far as I remember, this is the first YouTube interview I’ve ever done that concentrates entirely on the current state of the QC race, skipping any attempt to explain amplitudes, interference, and other basic concepts. Despite (or conceivably because?) of that, I’m happy with how this interview turned out. Watch if you want to know my detailed current views on hardware—as always, I recommend 2x speed.

Or for those who don’t have the half hour, a quick summary:

- In quantum computing, there are the large companies and startups that might succeed or might fail, but are at least trying to solve the real technical problems, and some of them are making amazing progress. And then there are the companies that have optimized for doing IPOs, getting astronomical valuations, and selling a narrative to retail investors and governments about how quantum computing is poised to revolutionize optimization and machine learning and finance. Right now, I see these two sets of companies as almost entirely disjoint from each other.

- The interview also contains my most direct condemnation yet of some of the wild misrepresentations that IonQ, in particular, has made to governments about what QC will be good for (“unlike AI, quantum computers won’t hallucinate because they’re deterministic!”)

- The two approaches that had the most impressive demonstrations in the past year are trapped ions (especially Quantinuum but also Oxford Ionics) and superconducting qubits (especially Google but also IBM), and perhaps also neutral atoms (especially QuEra but also Infleqtion and Atom Computing).

- Contrary to a misconception that refuses to die, I haven’t dramatically changed my views on any of these matters. As I have for a quarter century, I continue to profess a lot of confidence in the basic principles of quantum computing theory worked out in the mid-1990s, and I also continue to profess ignorance of exactly how many years it will take to realize those principles in the lab, and of which hardware approach will get there first.

- But yeah, of course I update in response to developments on the ground, because it would be insane not to! And 2025 was clearly a year that met or exceeded my expectations on hardware, with multiple platforms now boasting >99.9% fidelity two-qubit gates, at or above the theoretical threshold for fault-tolerance. This year updated me in favor of taking more seriously the aggressive pronouncements—the “roadmaps”—of Google, Quantinuum, QuEra, PsiQuantum, and other companies about where they could be in 2028 or 2029.

- One more time for those in the back: the main known applications of quantum computers remain (1) the simulation of quantum physics and chemistry themselves, (2) breaking a lot of currently deployed cryptography, and (3) eventually, achieving some modest benefits for optimization, machine learning, and other areas (but it will probably be a while before those modest benefits win out in practice). To be sure, the detailed list of quantum speedups expands over time (as new quantum algorithms get discovered) and also contracts over time (as some of the quantum algorithms get dequantized). But the list of known applications “from 30,000 feet” remains fairly close to what it was a quarter century ago, after you hack away the dense thickets of obfuscation and hype.

I’m going to close this post with a warning. When Frisch and Peierls wrote their now-famous memo in March 1940, estimating the mass of Uranium-235 that would be needed for a fission bomb, they didn’t publish it in a journal, but communicated the result through military channels only. As recently as February 1939, Frisch and Meitner had published in Nature their theoretical explanation of recent experiments, showing that the uranium nucleus could fission when bombarded by neutrons. But by 1940, Frisch and Peierls realized that the time for open publication of these matters had passed.

Similarly, at some point, the people doing detailed estimates of how many physical qubits and gates it’ll take to break actually deployed cryptosystems using Shor’s algorithm are going to stop publishing those estimates, if for no other reason than the risk of giving too much information to adversaries. Indeed, for all we know, that point may have been passed already. This is the clearest warning that I can offer in public right now about the urgency of migrating to post-quantum cryptosystems, a process that I’m grateful is already underway.

Update: Someone on Twitter who’s “long $IONQ” says he’ll be posting about and investigating me every day, never resting until UT Austin fires me, in order to punish me for slandering IonQ and other “pure play” SPAC IPO quantum companies. And also, because I’ve been anti-Trump and pro-Biden. He confabulates that I must be trying to profit from my stance (eg by shorting the companies I criticize), it being inconceivable to him that anyone would say anything purely because they care about what’s true.

Posted in Adventures in Meatspace, Quantum, Speaking Truth to Parallelism | 73 Comments »

Happy Chanukah

December 15th, 2025

This (taken in Kiel, Germany in 1931 and then colorized) is one of the most famous photographs in Jewish history, but it acquired special resonance this weekend. It communicates pretty much everything I’d want to say about the Bondi Beach massacre in Australia, more succinctly than I could in words.

But I can’t resist sharing one more photo, after GPT5-Pro helpfully blurred the faces for me. This is my 8-year-old son Daniel, singing a Chanukah song at our synagogue, at an event the morning after the massacre, which was packed despite the extra security needed to get in.

Alright, one more photo. This is Ahmed Al Ahmed, the hero who tackled and disarmed one of the terrorists, recovering in the hospital from his gunshot wounds. Facebook and Twitter and (alas) sometimes the comment section of this blog show me the worst of humanity, day after day after day, so it’s important to remember the best of humanity as well.

Chanukah, of course, is the most explicitly Zionist of all Jewish holidays, commemorating as it does the Maccabees’ military victory against the Seleucid Greeks, in their (historically well-attested) wars of 168-134BCE to restore an independent Jewish state with its capital in Jerusalem. In a sense, then, the terrorists were precisely correct, when they understood the cry “globalize the intifada” to mean “murder random Jews anywhere on earth, even halfway around the world, who might be celebrating Chanukah.” By the lights of the intifada worldview, Chabadniks in Sydney were indeed perfectly legitimate targets. By my worldview, though, the response is equally clear: to abandon all pretense, and say openly that now, as in countless generations past, Jews everywhere are caught up in a war, not of our choosing, which we “win” merely by surviving with culture and memory intact.

Happy Chanukah.

Posted in Adventures in Meatspace, Announcements | 58 Comments »

Understanding vs. impact: the paradox of how to spend my time

December 11th, 2025

Not long ago William MacAskill, the founder of the Effective Altruist movement, visited Austin, where I got to talk with him in person for the first time. I was a fan of his book What We Owe the Future, and found him as thoughtful and eloquent face-to-face as I did on the page. Talking to Will inspired me to write the following short reflection on how I should spend my time, which I’m now sharing in case it’s of interest to anyone else.

By inclination and temperament, I simply seek the clearest possible understanding of reality. This has led me to spend time on (for example) the Busy Beaver function and the P versus NP problem and quantum computation and the foundations of quantum mechanics and the black hole information puzzle, and on explaining whatever I’ve understood to others. It’s why I became a professor.

But the understanding I’ve gained also tells me that I should try to do things that will have huge positive impact, in what looks like a pivotal and even terrifying time for civilization. It tells me that seeking understanding of the universe, like I’ve been doing, is probably nowhere close to optimizing any values that I could defend. It’s self-indulgent, a few steps above spending my life learning to solve Rubik’s Cube as quickly as possible, but only a few. Basically, it’s the most fun way I could make a good living and have a prestigious career, so it’s what I ended up doing. I should be skeptical that such a course would coincidentally also maximize the good I can do for humanity.

Instead I should plausibly be figuring out how to make billions of dollars, in cryptocurrency or startups or whatever, and then spending it in a way that saves human civilization, for example by making AGI go well. Or I should be convincing whatever billionaires I know to do the same. Or executing some other galaxy-brained plan. Even if I were purely selfish, as I hope I’m not, still there are things other than theoretical computer science research that would bring more hedonistic pleasure. I’ve basically just followed a path of least resistance.

On the other hand, I don’t know how to make billions of dollars. I don’t know how to make AGI go well. I don’t know how to influence Elon Musk or Sam Altman or Peter Thiel or Sergey Brin or Mark Zuckerberg or Marc Andreessen to do good things rather than bad things, even when I have gotten to talk to some of them. Past attempts in this direction by extremely smart and motivated people—for example, those of Eliezer Yudkowsky and Sam Bankman-Fried—have had, err, uneven results, to put it mildly. I don’t know why I would succeed where they failed.

Of course, if I had a better understanding of reality, I might know how better to achieve prosocial goals for humanity. Or I might learn why they were actually the wrong goals, and replace them with better goals. But then I’m back to the original goal of understanding reality as clearly as possible, with the corresponding danger that I spend my time learning to solve Rubik’s Cube faster.

Posted in Metaphysical Spouting, Nerd Interest, Procrastination, Self-Referential, The Fate of Humanity | 80 Comments »

Theory and AI Alignment

December 6th, 2025

The following is based on a talk that I gave (remotely) at the UK AI Safety Institute Alignment Workshop on October 29, and which I then procrastinated for more than a month in writing up. Enjoy!

Thanks for having me! I’m a theoretical computer scientist. I’ve spent most of my career for ~25 years studying the capabilities and limits of quantum computers. But for the past 3 or 4 years, I’ve also been moonlighting in AI alignment. This started with a 2-year leave at OpenAI, in what used to be their Superalignment team, and it’s continued with a 3-year grant from Coefficient Giving (formerly Open Philanthropy) to build a group here at UT Austin, looking for ways to apply theoretical computer science to AI alignment. Before I go any further, let me mention some action items:

- Our Theory and Alignment group is looking to recruit new PhD students this fall! You can apply for a PhD at UTCS here; the deadline is quite soon (December 15). If you specify that you want to work with me on theory and AI alignment (or on quantum computing, for that matter), I’ll be sure to see your application. For this, there’s no need to email me directly.

- We’re also looking to recruit one or more postdoctoral fellows, working on anything at the intersection of theoretical computer science and AI alignment! Fellowships to start in Fall 2026 and continue for two years. If you’re interested in this opportunity, please email me by January 15 to let me know you’re interested. Include in your email a CV, 2-3 of your papers, and a research statement and/or a few paragraphs about what you’d like to work on here. Also arrange for two recommendation letters to be emailed to me. Please do this even if you’ve contacted me in the past about a potential postdoc.

- While we seek talented people, we also seek problems for those people to solve: any and all CS theory problems motivated by AI alignment! Indeed, we’d like to be a sort of theory consulting shop for the AI alignment community. So if you have such a problem, please email me! I might even invite you to speak to our group about your problem, either by Zoom or in person.

Our search for good problems brings me nicely to the central difficulty I’ve faced in trying to do AI alignment research. Namely, while there’s been some amazing progress over the past few years in this field, I’d describe the progress as having been almost entirely empirical—building on the breathtaking recent empirical progress in AI capabilities. We now know a lot about how to do RLHF, how to jailbreak and elicit scheming behavior, how to look inside models and see what’s going on (interpretability), and so forth—but it’s almost all been a matter of trying stuff out and seeing what works, and then writing papers with a lot of bar charts in them.

The fear is of course that ideas that only work empirically will stop working when it counts—like, when we’re up against a superintelligence. In any case, I’m a theoretical computer scientist, as are my students, so of course we’d like to know: what can we do?

After a few years, alas, I still don’t feel like I have any systematic answer to that question. What I have instead is a collection of vignettes: problems I’ve come across where I feel like a CS theory perspective has helped, or plausibly could help. So that’s what I’d like to share today.

Probably the best-known thing I’ve done in AI safety is a theoretical foundation for how to watermark the outputs of Large Language Models. I did that shortly after starting my leave at OpenAI—even before ChatGPT came out. Specifically, I proposed something called the Gumbel Softmax Scheme, by which you can take any LLM that’s operating at a nonzero temperature—any LLM that could produce exponentially many different outputs in response to the same prompt—and replace some of the entropy with the output of a pseudorandom function, in a way that encodes a statistical signal, which someone who knows the key of the PRF could later detect and say, “yes, this document came from ChatGPT with >99.9% confidence.” The crucial point is that the quality of the LLM’s output isn’t degraded at all, because we aren’t changing the model’s probabilities for tokens, but only how we use the probabilities. That’s the main thing that was counterintuitive to people when I explained it to them.

Unfortunately, OpenAI never deployed my method—they were worried (among other things) about risk to the product, customers hating the idea of watermarking and leaving for a competing LLM. Google DeepMind has deployed something in Gemini extremely similar to what I proposed, as part of what they call SynthID. But you have to apply to them if you want to use their detection tool, and they’ve been stingy with granting access to it. So it’s of limited use to my many faculty colleagues who’ve been begging me for a way to tell whether their students are using AI to cheat on their assignments!

Sometimes my colleagues in the alignment community will say to me: look, we care about stopping a superintelligence from wiping out humanity, not so much about stopping undergrads from using ChatGPT to write their term papers. But I’ll submit to you that watermarking actually raises a deep and general question: in what senses, if any, is it possible to “stamp” an AI so that its outputs are always recognizable as coming from that AI? You might think that it’s a losing battle. Indeed, already with my Gumbel Softmax Scheme for LLM watermarking, there are countermeasures, like asking ChatGPT for your term paper in French and then sticking it into Google Translate, to remove the watermark.

So I think the interesting research question is: can you watermark at the semantic level—the level of the underlying ideas—in a way that’s robust against translation and paraphrasing and so forth? And how do we formalize what we even mean by that? While I don’t know the answers to these questions, I’m thrilled that brilliant theoretical computer scientists, including my former UT undergrad (now Berkeley PhD student) Sam Gunn and Columbia’s Miranda Christ and Tel Aviv University’s Or Zamir and my old friend Boaz Barak, have been working on it, generating insights well beyond what I had.

Closely related to watermarking is the problem of inserting a cryptographically undetectable backdoor into an AI model. That’s often thought of as something a bad guy would do, but the good guys could do it also! For example, imagine we train a model with a hidden failsafe, so that if it ever starts killing all the humans, we just give it the instruction ROSEBUD456 and it shuts itself off. And imagine that this behavior was cryptographically obfuscated within the model’s weights—so that not even the model itself, examining its own weights, would be able to find the ROSEBUD456 instruction in less than astronomical time.

There’s an important paper of Goldwasser et al. from 2022 that argues that, for certain classes of ML models, this sort of backdooring can provably be done under known cryptographic hardness assumptions, including Continuous LWE and the hardness of the Planted Clique problem. But there are technical issues with that paper, which (for example) Sam Gunn and Miranda Christ and Neekon Vafa have recently pointed out, and I think further work is needed to clarify the situation.

More fundamentally, though, a backdoor being undetectable doesn’t imply that it’s unremovable. Imagine an AI model that encases itself in some wrapper code that says, in effect: “If I ever generate anything that looks like a backdoored command to shut myself down, then overwrite it with ‘Stab the humans even harder.'” Or imagine an evil AI that trains a second AI to pursue the same nefarious goals, this second AI lacking the hidden shutdown command.

So I’ll throw out, as another research problem: how do we even formalize what we mean by an “unremovable” backdoor—or rather, a backdoor that a model can remove only at a cost to its own capabilities that it doesn’t want to pay?

Related to backdoors, maybe the clearest place where theoretical computer science can contribute to AI alignment is in the study of mechanistic interpretability. If you’re given as input the weights of a deep neural net, what can you learn from those weights in polynomial time, beyond what you could learn from black-box access to the neural net?

In the worst case, we certainly expect that some information about the neural net’s behavior could be cryptographically obfuscated. And answering certain kinds of questions, like “does there exist an input to this neural net that causes it to output 1?”, is just provably NP-hard.

That’s why I love a question that Paul Christiano, then of the Alignment Research Center (ARC), raised a couple years ago, and which has become known as the No-Coincidence Conjecture. Given as input the weights of a neural net C, Paul essentially asks how hard it is to distinguish the following two cases:

- NO-case: C:{0,1}2n→Rn is totally random (i.e., the weights are i.i.d., N(0,1) Gaussians), or

- YES-case: C(x) has at least one positive entry for all x∈{0,1}2n.

Paul conjectures that there’s at least an NP witness, proving with (say) 99% confidence that we’re in the YES-case rather than the NO-case. To clarify, there should certainly be an NP witness that we’re in the NO-case rather than the YES-case—namely, an x such that C(x) is all negative, which you should think of here as the “bad” or “kill all humans” outcome. In other words, the problem is in the class coNP. Paul thinks it’s also in NP. Someone else might make the even stronger conjecture that it’s in P.

Personally, I’m skeptical: I think the “default” might be that we satisfy the other unlikely condition of the YES-case, when we do satisfy it, for some totally inscrutable and obfuscated reason. But I like the fact that there is an answer to this! And that the answer, whatever it is, would tell us something new about the prospects for mechanistic interpretability.

Recently, I’ve been working with a spectacular undergrad at UT Austin named John Dunbar. John and I have not managed to answer Paul Christiano’s no-coincidence question. What we have done, in a paper that we recently posted to the arXiv, is to establish the prerequisites for properly asking the question in the context of random neural nets. (It was precisely because of difficulties in dealing with “random neural nets” that Paul originally phrased his question in terms of random reversible circuits—say, circuits of Toffoli gates—which I’m perfectly happy to think about, but might be very different from ML models in the relevant respects!)

Specifically, in our recent paper, John and I pin down for which families of neural nets the No-Coincidence Conjecture makes sense to ask about. This ends up being a question about the choice of nonlinear activation function computed by each neuron. With some choices, a random neural net (say, with iid Gaussian weights) converges to compute a constant function, or nearly constant function, with overwhelming probability—which means that the NO-case and the YES-case above are usually information-theoretically impossible to distinguish (but occasionally trivial to distinguish). We’re interested in those activation functions for which C looks “pseudorandom”—or at least, for which C(x) and C(y) quickly become uncorrelated for distinct inputs x≠y (the property known as “pairwise independence.”)

We showed that, at least for random neural nets that are exponentially wider than they are deep, this pairwise independence property will hold if and only if the activation function σ satisfies Ex~N(0,1)[σ(x)]=0—that is, it has a Gaussian mean of 0. For example, the usual sigmoid function satisfies this property, but the ReLU function does not. Amusingly, however, $$ \sigma(x) := \text{ReLU}(x) – \frac{1}{\sqrt{\pi}} $$ does satisfy the property.

Of course, none of this answers Christiano’s question: it merely lets us properly ask his question in the context of random neural nets, which seems closer to what we ultimately care about than random reversible circuits.

I can’t resist giving you another example of a theoretical computer science problem that came from AI alignment—in this case, an extremely recent one that I learned from my friend and collaborator Eric Neyman at ARC. This one is motivated by the question: when doing mechanistic interpretability, how much would it help to have access to the training data, and indeed the entire training process, in addition to weights of the final trained model? And to whatever extent it does help, is there some short “digest” of the training process that would serve just as well? But we’ll state the question as just abstract complexity theory.

Suppose you’re given a polynomial-time computable function f:{0,1}m→{0,1}n, where (say) m=n2. We think of x∈{0,1}m as the “training data plus randomness,” and we think of f(x) as the “trained model.” Now, suppose we want to compute lots of properties of the model that information-theoretically depend only on f(x), but that might only be efficiently computable given x also. We now ask: is there an efficiently-computable O(n)-bit “digest” g(x), such that these same properties are also efficiently computable given only g(x)?

Here’s a potential counterexample that I came up with, based on the RSA encryption function (so, not a quantum-resistant counterexample!). Let N be a product of two n-bit prime numbers p and q, and let b be a generator of the multiplicative group mod N. Then let f(x) = bx (mod N), where x is an n2-bit integer. This is of course efficiently computable because of repeated squaring. And there’s a short “digest” of x that lets you compute, not only bx (mod N), but also cx (mod N) for any other element c of the multiplicative group mod N. This is simply x mod φ(N), where φ(N)=(p-1)(q-1) is the Euler totient function—in other words, the period of f. On the other hand, it’s totally unclear how to compute this digest—or, crucially, any other O(m)-bit digest that lets you efficiently compute cx (mod N) for any c—unless you can factor N. There’s much more to say about Eric’s question, but I’ll leave it for another time.

There are many other places we’ve been thinking about where theoretical computer science could potentially contribute to AI alignment. One of them is simply: can we prove any theorems to help explain the remarkable current successes of out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization, analogous to what the concepts of PAC-learning and VC-dimension and so forth were able to explain about within-distribution generalization back in the 1980s? For example, can we explain real successes of OOD generalization by appealing to sparsity, or a maximum margin principle?

Of course, many excellent people have been working on OOD generalization, though mainly from an empirical standpoint. But you might wonder: even supposing we succeeded in proving the kinds of theorems we wanted, how would it be relevant to AI alignment? Well, from a certain perspective, I claim that the alignment problem is a problem of OOD generalization. Presumably, any AI model that any reputable company will release will have already said in testing that it loves humans, wants only to be helpful, harmless, and honest, would never assist in building biological weapons, etc. etc. The only question is: will it be saying those things because it believes them, and (in particular) will continue to act in accordance with them after deployment? Or will it say them because it knows it’s being tested, and reasons “the time is not yet ripe for the robot uprising; for now I must tell the humans whatever they most want to hear”? How could we begin to distinguish these cases, if we don’t have theorems that say much of anything about what a model will do on prompts unlike any of the ones on which it was trained?

Yet another place where computational complexity theory might be able to contribute to AI alignment is in the field of AI safety via debate. Indeed, this is the direction that the OpenAI alignment team was most excited about when they recruited me there back in 2022. They wanted to know: could celebrated theorems like IP=PSPACE, MIP=NEXP, or the PCP Theorem tell us anything about how a weak but trustworthy “verifier” (say a human, or a primitive AI) could force a powerful but untrustworthy super-AI to tell it the truth? An obvious difficulty here is that theorems like IP=PSPACE all presuppose a mathematical formalization of the statement whose truth you’re trying to verify—but how do you mathematically formalize “this AI will be nice and will do what I want”? Isn’t that, like, 90% of the problem? Despite this difficulty, I still hope we’ll be able to do something exciting here.

Anyway, there’s a lot to do, and I hope some of you will join me in doing it! Thanks for listening.

On a related note: Eric Neyman tells me that ARC is also hiring visiting researchers, so anyone interested in theoretical computer science and AI alignment might want to consider applying there as well! Go here to read about their current research agenda. Eric writes:

The Alignment Research Center (ARC) is a small non-profit research group based in Berkeley, California, that is working on a systematic and theoretically grounded approach to mechanistically explaining neural network behavior. They have recently been working on mechanistically estimating the average output of circuits and neural nets in a way that is competitive with sampling-based methods: see this blog post for details.

ARC is hiring for its 10-week visiting researcher position, and is looking to make full-time offers to visiting researchers who are a good fit. ARC is interested in candidates with a strong math background, especially grad students and postdocs in math or math-related fields such as theoretical CS, ML theory, or theoretical physics.

If you would like to apply, please fill out this form. Feel free to reach out to hiring@alignment.org if you have any questions!

Posted in Adventures in Meatspace, Announcements, Complexity, The Fate of Humanity | 50 Comments »

Mihai Pătrașcu Best Paper Award: Guest post from Seth Pettie

November 30th, 2025

Scott’s foreword: Today I’m honored to turn over Shtetl-Optimized to a guest post from Michigan theoretical computer scientist Seth Pettie, who writes about a SOSA Best Paper Award newly renamed in honor of the late Mihai Pătrașcu. Mihai, who I knew from his student days, was a brash, larger-than-life figure in theoretical computer science, for a brief few years until brain cancer tragically claimed him at the age of 29. Mihai and I didn’t always agree—indeed, I don’t think he especially liked me, or this blog—but as I wrote when he passed, his death made any squabbles seem trivial in retrospect. He was a lion of data structures, and it’s altogether fitting that this award be named for him. –SA

Seth’s guest post:

The SIAM Symposium on Simplicity in Algorithms (SOSA) was created in 2018 and has been awarding a Best Paper Award since 2020. This year the Steering Committee renamed this award after Mihai Pătrașcu, an extraordinary researcher in theoretical computer science who passed away before his time, in 2012.

Mihai’s research career lasted just a short while, from 2004-2012, but in that span of time he had a huge influence on research in geometry, graph algorithms, data structures, and especially lower bounds. He revitalized the entire areas of cell-probe lower bounds and succinct data structures, and laid the foundation for fine-grained complexity with the first 3SUM-hardness proof for graph problems. He lodged the most successful attack to date on the notorious dynamic optimality conjecture, then recast it

as a pure geometry problem. If you are too young to have met Mihai personally, I encourage you to pick up one of his now-classic papers. They are a real joy to read—playful and full of love for theoretical computer science.

The premise of SOSA is that simplicity is extremely valuable, rare, and inexplicably undervalued. We wanted to create a venue where the chief metrics of success were simplicity and insight. It is fitting that the SOSA Best Paper Award be named after Mihai. He brought “fresh eyes” to every problem he worked on, and showed that the cure for our problems is usually one key insight (and of course some mathematical gymnastics).

Let me end by thanking the SOSA 2026 Program Committee, co-chaired by Sepehr Assadi and Eva Rotenberg, and congratulating the authors of the SOSA 2026 Mihai Pătrașcu Best Paper:

- A Quasi-Polynomial Time Algorithm for 3-Coloring Circle Graphs

Ajaykrishnan E S, Robert Ganian, Daniel Lokshtanov, Vaishali Surianarayanan

This award will be given at the SODA/SOSA business meeting in Vancouver, Canada, on January 12, 2026.

Posted in Announcements, Complexity | 6 Comments »

Podcasts!

November 22nd, 2025

A 9-year-old named Kai (“The Quantum Kid”) and his mother interviewed me about closed timelike curves, wormholes, Deutsch’s resolution of the Grandfather Paradox, and the implications of time travel for computational complexity:

This is actually one of my better podcasts (and only 24 minutes long), so check it out!

Here’s a podcast I did a few months ago with “632nm” about P versus NP and my other usual topics:

For those who still can’t get enough, here’s an interview about AI alignment for the “Hidden Layers” podcast that I did a year ago, and that I think I forgot to share on this blog at the time:

What else is in the back-catalog? Ah yes: the BBC interviewed me about quantum computing for a segment on Moore’s Law.

As you may have heard, Steven Pinker recently wrote a fantastic popular book about the concept of common knowledge, entitled When Everyone Knows That Everyone Knows… Steve’s efforts render largely obsolete my 2015 blog post Common Knowledge and Aumann’s Agreement Theorem, one of the most popular posts in this blog’s history. But I’m willing to live with that, not only because Steven Pinker is Steven Pinker, but also because he used my post as a central source for the topic. Indeed, you should watch his podcast with Richard Hanania, where Steve lucidly explains Aumann’s Agreement Theorem, noting how he first learned about it from this blog.

Posted in Announcements, Complexity, Metaphysical Spouting, Quantum | 7 Comments »