Neanderthals and Homo sapiens shared technology and customs in the Levant, shaping early human culture through cooperation.

The first published study on Tinshemet Cave reveals that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens in the mid-Middle Paleolithic Levant not only lived side by side but also interacted closely. They shared tools, daily practices, and burial customs—evidence of meaningful cultural exchange.

These interactions encouraged social complexity and sparked behavioral innovations, including some of the earliest formal burials and the symbolic use of ochre for decoration. The findings suggest that collaboration, rather than isolation, played a key role in driving early human development. This positions the Levant as a vital crossroads in the story of human evolution.

Located in central Israel, Tinshemet Cave offers new insights into human relationships during the Middle Paleolithic period in the Near East. The site has yielded rich archaeological and anthropological evidence, including the first mid-middle Paleolithic burials discovered in over fifty years.

Published in Nature Human Behaviour, this is the first scientific report on Tinshemet Cave. It provides strong evidence that Neanderthals and Homo sapiens not only coexisted in the region but also shared elements of daily life, technology, and mortuary practices. These findings point to a deeper and more complex relationship between the two species than previously thought.

Investigating Human Relationships in the Levant

The excavation of Tinshemet Cave, led by Prof. Yossi Zaidner of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Prof. Israel Hershkovitz of Tel Aviv University, and Dr. Marion Prévost of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, has been ongoing since 2017.

A primary goal of the research team is to determine the nature of Homo sapiens–Neanderthal relationships in the mid-Middle Palaeolithic Levant. Were they rivals competing for resources, peaceful neighbors, or even collaborators?

By integrating data from four key fields—stone tool production, hunting strategies, symbolic behavior, and social complexity—the study argues that different human groups, including Neanderthals, pre-Neanderthals, and Homo sapiens, engaged in meaningful interactions.

These exchanges facilitated knowledge transmission and led to the gradual cultural homogenization of populations. The research suggests that these interactions spurred social complexity and behavioral innovations.

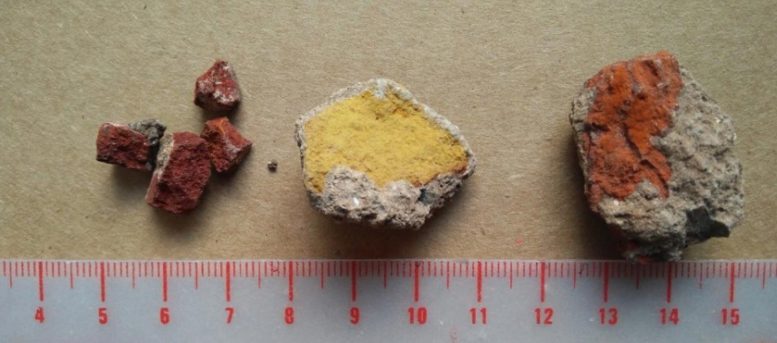

For instance, formal burial customs began to appear around 110,000 years ago in Israel for the first time worldwide, likely as a result of intensified social interactions. A striking discovery at Tinshemet Cave is the extensive use of mineral pigments, particularly ochre, which may have been used for body decoration. This practice could have served to define social identities and distinctions among groups.

Burial Practices and Symbolic Behavior

The clustering of human burials at Tinshemet Cave raises intriguing questions about its role in MP society. Could the site have functioned as a dedicated burial ground or even a cemetery? If so, this would suggest the presence of shared rituals and strong communal bonds. The placement of significant artifacts—such as stone tools, animal bones, and ochre chunks—within the burial pits may further indicate early beliefs in the afterlife.

Prof. Zaidner describes Israel as a “melting pot” where different human groups met, interacted, and evolved together. “Our data show that human connections and population interactions have been fundamental in driving cultural and technological innovations throughout history,” he explains.

Dr. Prévost highlights the unique geographic position of the region at the crossroads of human dispersals. “During the mid-MP, climatic improvements increased the region’s carrying capacity, leading to demographic expansion and intensified contact between different Homo taxa.”

Prof. Hershkovitz adds that the interconnectedness of lifestyles among various human groups in the Levant suggests deep relationships and shared adaptation strategies. “These findings paint a picture of dynamic interactions shaped by both cooperation and competition.”

The discoveries at Tinshemet Cave offer a fascinating glimpse into the social structures, symbolic behaviors, and daily lives of early human groups. They reveal a period of profound demographic and cultural transformations, shedding new light on the complex web of interactions that shaped our ancestors’ world. As excavations continue, Tinshemet Cave promises to provide even deeper insights into the origins of human society.

Reference: “Evidence from Tinshemet Cave in Israel suggests behavioral uniformity across Homo groups in the Levantine mid-Middle Palaeolithic circa 130,000–80,000 years ago” by Yossi Zaidner, Marion Prévost, Ruth Shahack-Gross, Lior Weissbrod, Reuven Yeshurun, Naomi Porat, Gilles Guérin, Norbert Mercier, Asmodée Galy, Christophe Pécheyran, Gaëlle Barbotin, Chantal Tribolo, Hélène Valladas, Dustin White, Rhys Timms, Simon Blockley, Amos Frumkin, David Gaitero-Santos, Shimon Ilani, Sapir Ben-Haim, Antonella Pedergnana, Alyssa V. Pietraszek, Pedro García, Cristiano Nicosia, Susan Lagle, Oz Varoner, Chen Zeigen, Dafna Langgut, Onn Crouvi, Sarah Borgel, Rachel Sarig, Hila May and Israel Hershkovitz, 11 March 2025, Nature Human Behaviour.

DOI: 10.1038/s41562-025-02110-y

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily newsletter.

Follow us on Google and Google News.