- Lesedauer ca. 4 Minuten

Good passwords are hard to remember. A pattern that makes a password memorable is likely to make it vulnerable to attack. If remembering one secure password is hard, remembering many such passwords is entirely impractical. So people who have gone to the effort of creating one good password use it for many different accounts. A security breach anywhere that password is used means that the password is vulnerable everywhere else it is used.

It is much safer to have different passwords for every account. Then if one password is compromised, the damage is limited to a single account. One way to accomplish this would be to have software compute a password for each account by encrypting the name of the account. For example, your password for Home Depot could be the result of encrypting the text “homedepot.” This way accounts with different names would automatically have different passwords. (In practice, it might be possible but highly unlikely for two account names to result in the same password.)

If you generate your passwords this way, you have to trust the software that is generating them. What if that software turns out to have a security hole, either as a result of malice or error? If you could carry out the encryption in your head, you would not need to trust any software.

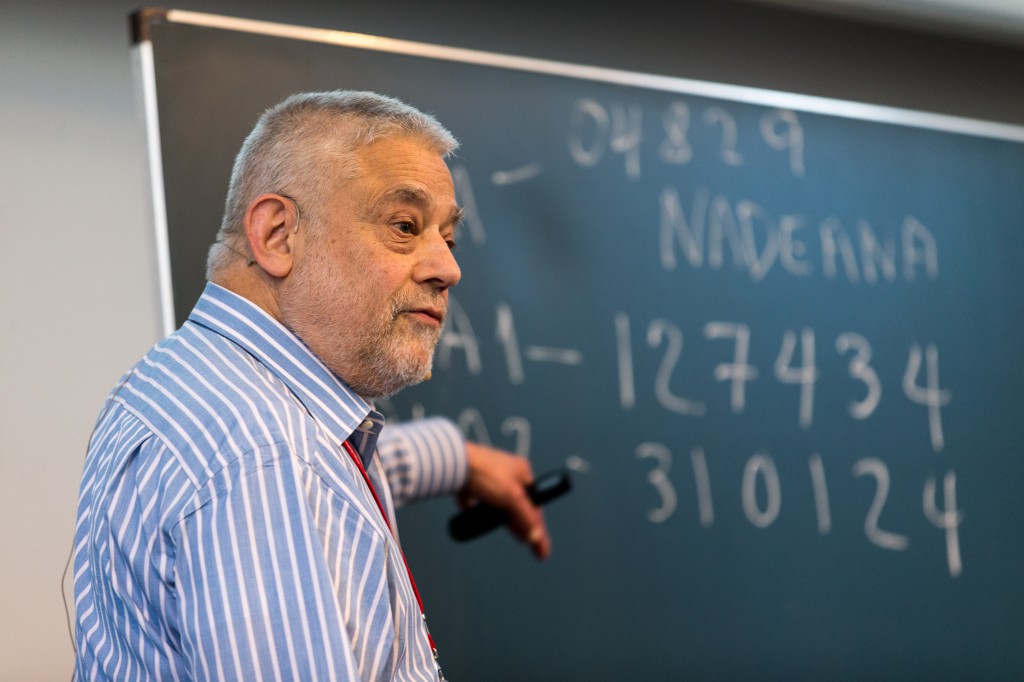

Is it possible to create encryption algorithms that a human can execute but that a computer cannot break? It doesn’t seem at first that this should be possible, but Turing Award winner Manuel Blum believes it may be. He presented his proposed algorithm at the Heidelberg Laureate Forum. He emphasized that his method takes a lot of up-front effort to learn but then it can be carried out quickly. To prove this claim, he demonstrated that at least one person has in fact used the method, namely himself! He said he can usually come up with a password in under 20 seconds.

Credit: hlff / Flemming

To use Blum’s method you must memorize two things: a random mapping of letters to digits, and a random permutation of the digits 0 through 9. The random map and the random permutation are your personal keys so you must keep them secret. They must be truly random — any pattern that makes them easier to memorize may make your system easier to break — and that’s why this up-front memorization is hard. But it only has to be done once.

Call your mapping of letters to digits f. You might have, for example, f(a) = 8, f(b) = 3, f(c) = 7, etc. Since there are more letters than digits, some letters will be mapped to the same digit.

Let g be the function that sends each digit to the next one in your permutation. So if your permutation was 0298736514 then g(0) = 2, g(2) = 9, g(9) = 8, etc.

Now here is how you use the method to generate passwords.

- Convert the name of your account to a sequence of n letters.

- Turn this sequence of letters into a sequence of digits using your map f. Call this sequence of digits a0a1a2…an.

- Compute b1, the first digit of your password, by adding a1 and an, taking the last digit, and applying the permutation g. In symbols, b1 = g( (a1 + an) mod 10 ).

- Compute the subsequent digits by bj = g( (bj-1 + aj) mod 10 ).

So if your account name converts to “abc” in step 1, this becomes 837 in step 2. The first digit of your password would be 1 because the first and last digits of 837 add to 15, and g(5) = 1. The second digit would be 0 because the previously computed password digit, 1, and the second digit of 837 add to 4 and g(4) = 0. The third digit would be 3 because 0+7 = 7 and g(7) = 3. Thus your password would be 103. (In practice your account names would need to map to more than just three characters, but using “abc” kept the example short.)

The way you create a sequence of letters for an account could be anything you like. For example, you could add your dog’s name to the end of every account name if you’d like. If a particular password is compromised, you could change your password by putting something new on the end, say the name of your neighbor’s dog, and going through the encryption process again.

This method only produces digits. If a particular account requires, for example, that all passwords contain a letter and a punctuation mark, you could stick an arbitrary fixed sequence like “k$” on the end of the digits. If the digits produced by Blum’s algorithm create a secure password, always adding the same characters on the end makes the password no less secure.

Blum’s method is practical, though it takes memorization and practice. More generally, it is an illustration of a research into the possibilities of human computation.