Even the name is confusing. Knife steel. Butcher’s steel. Honing rod. Sharpening steel. Do they remove metal or just “re-align” the edge? What does “re-align” mean? Are “honing” and “sharpening” different things? Scanning through opinions found on the internet will leave you more confused than enlightened. This series examines what actually happens at microscopic scale.

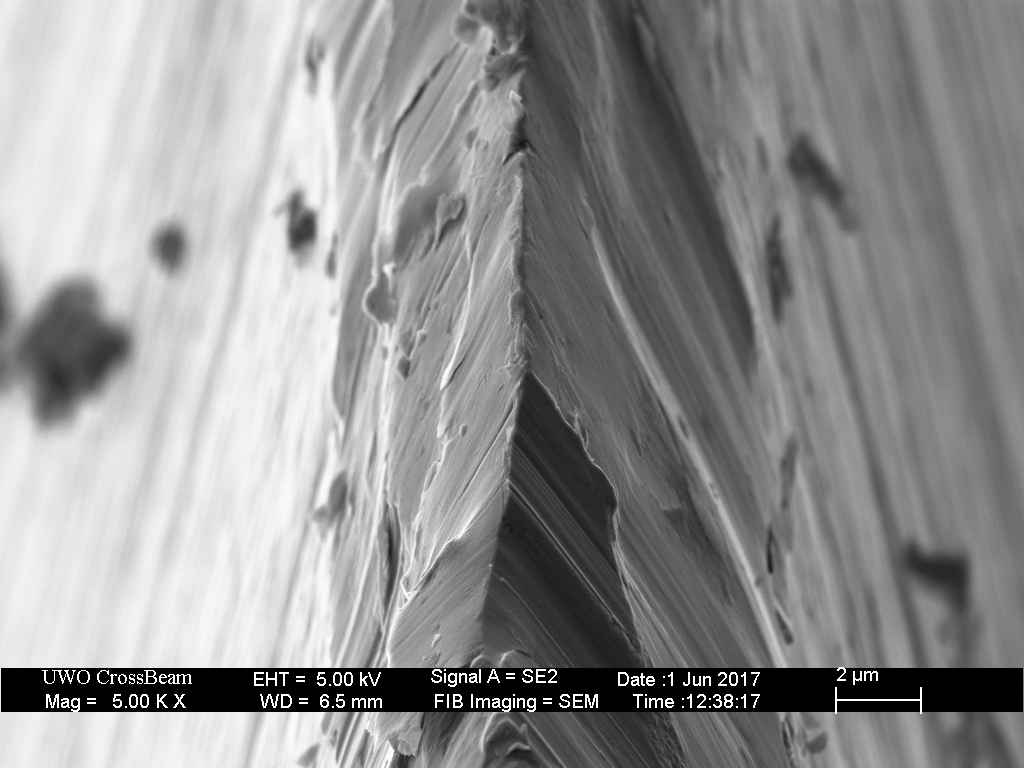

It is a common misconception that steeling does not remove metal, but simply “re-aligns the edge.” I have shown that re-alignment is one of the four results of stropping in What Does Stropping Do? However, in my experience this type of re-alignment rarely occurs. In the vast majority of cases, the steel near the apex is too damaged to be straightened, and instead simply breaks away rather than realign. Secondly, with typical use in slicing applications, blades usually become “dull” through abrasion (including micro-chipping) or blunting and thickening of the apex, rather than by rolling (or “major deflection”) of the edge. Rolling-like deflection can occur in a limited number of cases; for example by cutting into the non-abrasive lip of a glass. More commonly, cutting non-abrasive materials produces a blunted, mushroom-shaped apex, as shown in the image below.

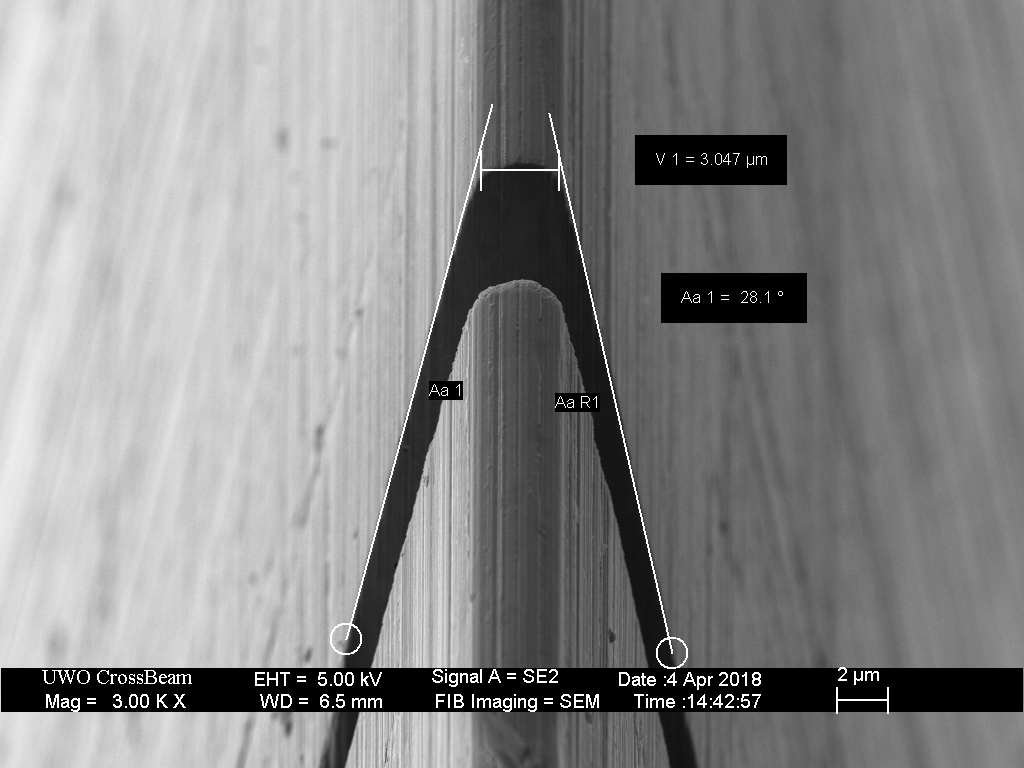

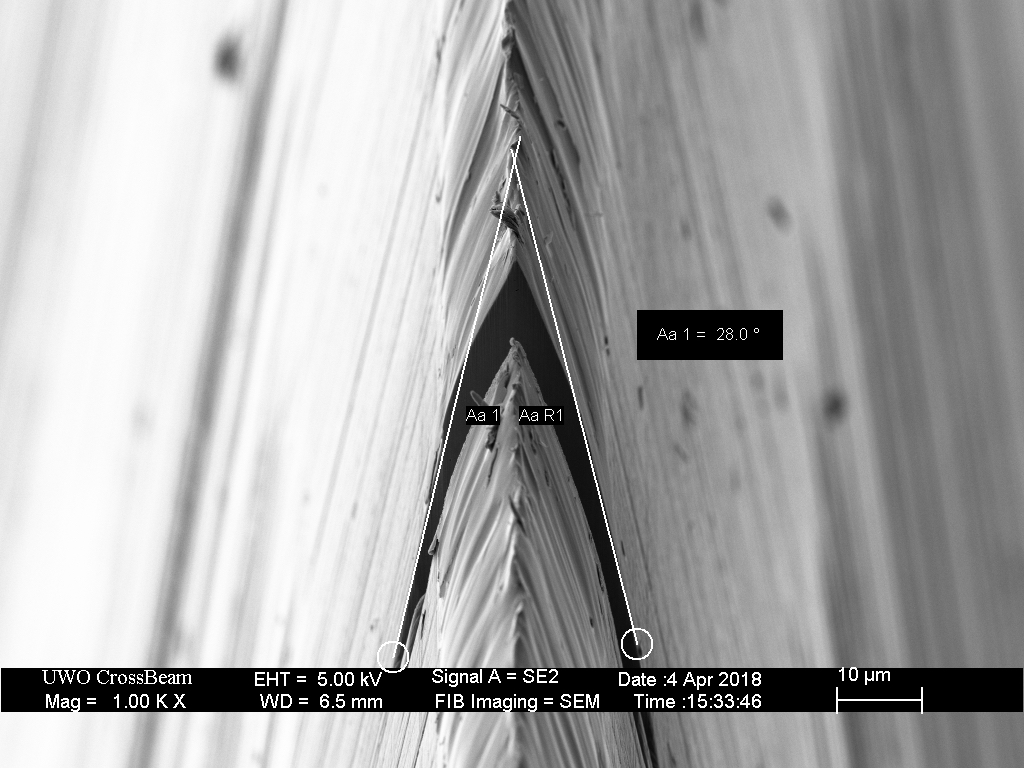

One of the first articles I wrote on this blog was to define the terms “sharp” and “keen” as they relate to sharpening/honing/stropping blades. In this series of articles, I will demonstrate the effect of steeling with the various types of honing rods, and show that steeling improves keenness by removing metal. In simple terms, steeling primarily produces a micro-bevel. To be consistent with these definitions, steeling does not sharpen the blade – if we accept that sharpening requires thinning the blade by grinding the bevel. For example, we may choose to sharpen a knife at 30 degrees (15 degrees per side) creating a millimeter wide bevel and then maintain the cutting ability of the knife by steeling at 20 degrees per side (40 degrees inclusive) to form a micro-bevel.

For this study I primarily use Olfa carbon steel cutting blades and dull them with a few cutting passes into the edge of sharpening stone. This produces a blunt apex with minimal damage to the underlying steel.

When “steeling” the edge, I use the traditional edge-leading, heel to tip slicing motion with light force applied at an angle slightly higher than that of the existing bevel. A range of honing rods are compared; a traditional ribbed steel (Wustof), a smooth ceramic rod, a smooth/polished “butcher’s” steel (Victorinox), a tungsten carbide sharpener (Chestnut tools Universal Sharpener), the Spyderco Sharpmaker (204MF) and a diamond-embedded rod. In part 1 of this study, I will demonstrate that steeling improves keenness through metal removal rather than “re-alignment of the edge.”

Ribbed Steel

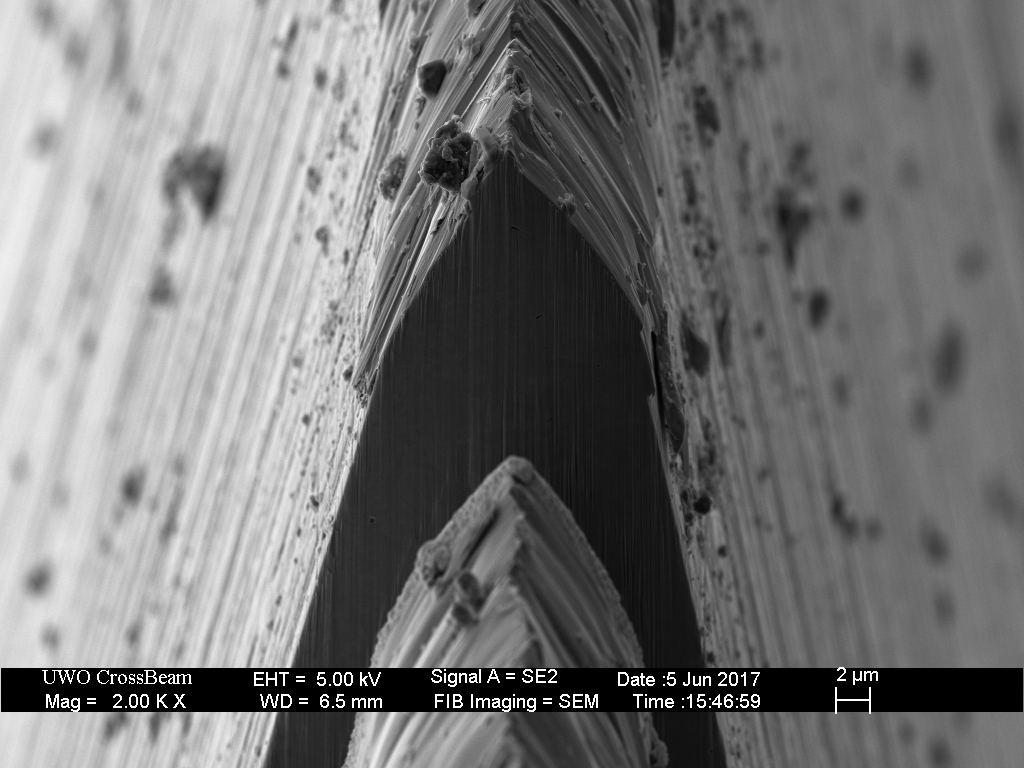

The set of images below demonstrate that the traditional ribbed knife steel does not “re-align” a “rolled” or deflected apex. The rod simply produces a micro-bevel. In the first image, the profile of the “factory” edge of the blade is shown and in the second image, the same blade after “rolling the edge.”

The blade was then steeled in the traditional fashion, edge leading at an angle of approximately 30 degrees. The blade was imaged, confirming that keenness had been restored to the apex and revealing that this was achieved by removal of steel; creating a new micro-bevel. There is some evidence of softened metal being redistributed; however, a micro-bevel is unquestionably formed through metal removal.

Ceramic Rod

Unlike the traditional metal butcher’s steel, it is undeniable that a ceramic honing rod removes metal, since the black steel swarf is visible on the white surface after use. In the following example, the blade was dulled by cutting into an abrasive stone, leaving a cleanly blunted apex. Honing with the ceramic rod is also observed to produce a micro-bevel with a keen apex.

In the SWARF! article, it was shown that traditional hones remove metal by cutting furrows into the metal of the blade producing curled metal chips – microscopic versions of the chips found in any metal fabrication shop. This type of metal removal is generally termed abrasive wear and occurs when a hard, sharp abrasive cuts into a softer metal surface.

Traditional honing rods do not have sharp protrusions, and the metal swarf found on the surface is observed as flattened or smeared patches of metal. This type of metal removal (or transfer) is generally termed adhesive wear. Adhesive wear occurs at points of very high pressure that occur when the contact area is very small.

Ceramic “steels” have become common and are often preferred to traditional ribbed knife steel. Although these ceramics are composed of micro-sized sintered grains, the surfaces are relatively smooth and do not display a “grit-like” texture. These rods appear to remove metal predominantly via adhesive wear rather than abrasive wear (grinding).

It is commonly suggested that honing rods are “only effective for simple and soft steel” blades. In the following example, steeling a high hardness vanadium steel blade (Buck, S30V) is shown to produce a microbevel in same manner as observed in the carbon steel Olfa blade. In this case, the knife was freehand sharpened at about 30 degrees (inclusive) and used as an every day carry for routine tasks until it was in need of sharpening. The first two images, below, show that the blade deteriorated by both blunting and chipping and also some slight deflection occurred in one area. It is noteworthy that the deflection occurs at a much larger length scale and independent of the blunting.

The knife was “steeled” with edge leading strokes in a slicing motion at about 25 degrees on the ceramic rod. The image below shows that, once again, steel has been remove to form a microbevel with a relatively keen apex. Note that this image is taken with the same magnification (scale) as the mushroomed apex image.

Polished (Smooth) Steel Rod

Abrasive wear typically requires ‘sharp’ grit-like features to scratch or cut into the steel, while adhesive wear does not. Instead, adhesive wear occurs when the local pressure at a relatively smooth “bump” is very high. Pressure is defined by the applied force divided by the contact area. As a result, when the contact area is microscopically small, the local pressure will be extremely large. When steeling a dull knife, at an angle higher than that of the existing bevel, the contact area is microscopically small since contact occurs only along the width of the newly formed micro-bevel. While this bevel is less than a few microns wide, the local pressure (even with light applied force) will be sufficiently high to enable adhesive wear to occur.

In the example below, the Olfa blade was dulled by cutting into an abrasive stone, and then steeled with a smooth, polished steel rod (Victorinox Honing Steel – round smooth polish). Once again, a obvious micro-bevel has been formed through metal removal.

….to continued in part 2….