Editor’s note: Today’s post is by Josh Nicholson, PhD, Chief Strategy Officer at Research Solutions, Inc., and Co-founder of Scite.

The recent leap in generative AI technology, led by companies like OpenAI, Anthropic, Google, and Microsoft, has sparked both awe and anxiety across industries. But while these models are impressive, they remain fundamentally limited by the quality and scope of the data they can access. In general, large language models (LLMs) cannot access research articles beyond abstracts or open-access articles. For the scientific and publishing communities, this presents both a challenge and an opportunity.

LLMs are not yet capable of meaningfully engaging with most peer-reviewed research articles. Why? Because most of the content is locked behind paywalls and isn’t accessible. If LLMs are the future of information discovery, valuable research disseminated by scholarly publishers risks being left behind — unless we build a bridge between authoritative research and intelligent retrieval.

Many publishers have been reluctant to engage with large AI companies for a variety of reasons. Some believe AI companies are infringing on their copyright, some believe this could significantly threaten their business, and others are waiting to see how their peers act. There is an arc of how publishers interact with AI and AI companies: at one end of the spectrum are groups that are blocking and fighting AI companies, while others announce large licensing deals and have formed direct partnerships (see Wiley’s recent announcement with Anthropic). Because of the confusion, threats, and ever-shifting technology, there is a gap between the latest AI and the most reputable content online — research articles. While this seems like a new challenge, it is reminiscent of the early days of the web, when new pages filled with information were being created at a scale never seen before. As Sergey Brin and Larry Page noted in their seminal paper, “web pages proliferate free of quality control” and “a random archived message posting asking an obscure question about an IBM computer is very different from the IBM home page.” This is very similar to LLMs and chatbots — because it is exceedingly easy to use and find value in services like ChatGPT, it is the fastest-growing product in history. Yet, it is very hard to tell what ChapGPT content is authoritative or hallucinated.

Because of the confusion, threats, and ever-shifting technology, there is a gap between the latest AI and the most reputable content online — research articles. While this seems like a new challenge, it is reminiscent of the early days of the web, when new pages filled with information were being created at a scale never seen before. As Sergey Brin and Larry Page noted in their seminal paper, “web pages proliferate free of quality control” and “a random archived message posting asking an obscure question about an IBM computer is very different from the IBM home page.” This is very similar to LLMs and chatbots — because it is exceedingly easy to use and find value in services like ChatGPT, it is the fastest-growing product in history. Yet, it is very hard to tell what ChapGPT content is authoritative or hallucinated.

Similar to the early days of the web, AI companies are looking for better ways to provide users with verifiable and accurate information. ChatGPT initially had no references; now, it references sources in web pages and even scientific articles, albeit only open ones, through a process called Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG).

The AI system will only ever be as good as the content it is trained on or the content it can interact with. This often results in made-up or incomplete content, at best. Like the early days of the web, scientific publishing might be part of the solution — in particular, citations.

The challenge of identifying a trustworthy web page versus a less trustworthy web page was largely solved through PageRank, which was directly influenced by citation analysis and scientific publishing. In their seminal piece, Brin and Page state that PageRank “provides a more sophisticated method for doing citation counting.” Eugene Garfield, the creator of the first science citation index, was even cited by Brin and Page. Thus, citations contributed to helping make the web more trustworthy and useful. I think citations can do the same with LLMs.

Citations & LLMs

Over the past decade, I have been thinking a lot about citations. Citations are largely used as a currency in science, a metric of success (or failure), and something researchers and journals lust after. One of my favorite papers captures this well with its title: C.R.E.A.M: Citations Rule Everything Around Me. Despite the fervent interest in citations, they have been presented in pretty much the same way since they were conceived — a list of papers that refer to the article. Traditional citations do not show how or why an article has been cited, simply that it has. Research, however, shows there are dozens of reasons for citing an article.

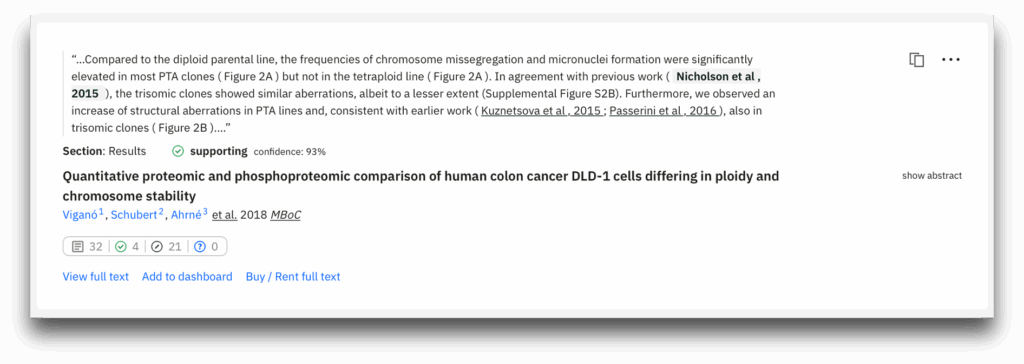

We’ve been working to improve citations at Scite by surfacing the actual in-text citation statements from citing articles, showing where those statements appear in the document, and indicating whether the cited claim is supported or contrasted. (NOTE: For full disclosure, I am the co-founder of Scite, which was acquired by my current employer.) These enhanced snippets, which we call Smart Citations, enable the systematic development of verifiable answers to research questions.

Crucially, our work to build the next generation of citations is created under indexing agreements directly with publishers. I think there is a function here for AI companies and publishers that can help bridge the gap in a way that protects researchers and publishers, yet connects the most powerful LLMs in the world to the most authoritative content.

Smart Citations (or their equivalent) could serve as a model for licensing research articles to LLMs for use in Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG). A pan-publisher unified dataset of annotated citations could be sublicensed, and usage could be tracked (even in a COUNTER-compatible way). I believe it is a new way to responsibly bridge the gap between AI / LLMs and scientific publishers.

This model delivers clear wins:

- Attribution: If an LLM can’t interact with an article, it can’t cite it. By directly licensing content in a controlled way, content would be more likely to be surfaced and cited in chatbots.

- Reliability: LLMs are hard to trust. By linking LLMs to authoritative content, their outputs become more trustworthy and comprehensive. Citation snippets could be surfaced for easy verification by the end user without taking away value from the version of record.

- Discovery: Similar to abstracts helping content be more discoverable on the web while not giving up the entire article, citation snippets would preserve the version of record and drive researchers’ and publishers’ traffic.

- Compensation: Publishers would be remunerated for the use of the version of record in a discovery environment. The more times an LLM interacts with the article, the more times the content is paid for, whether that is a “pay to crawl” type of licensing or as part of a subscription package demonstrating usage. Think of “AI reads” as the new reads and downloads.

This approach could be expanded, building the next generation of citations not just for the research space but building them for LLMs. The chatbots are being used by real people with real questions, sometimes directly impacting their lives in very serious ways. We as a community ought to think about how we can ensure society and the world have the best information possible. I think publishers are now more important than ever.