This is the story of a traditionally published sci-fi author who received more than fifty scam book-marketing pitches in thirty-three days, all hoping to prey on his desperation to sell books and net his next publishing deal.

We’ll call him Rob.

It’s also the story of a plucky, persistent, puzzled AI named Veronica and a scammer who steals real authors’ identities in order to get their marks’ guards down.

But mostly, it’s the story of what happens when an entire industry is drowning, and the people holding out life preservers are running a con.

The wave began with Mercy Gold (which is a great name for a werewolf hunter or demon slayer, BTW).

“Hello,” her email started. “You’ve already laid a great foundation with your blurb and keywords that’s a strong start.”

A compliment sandwich, I know them well. You’re doing great, BUT there’s a problem you didn’t know you had. She offered to help me manage “light social presence and simple email marketing” to keep my book “in front of real readers.” Would I be open to seeing how this could support my “author journey”?

The email came from mercygold7400@gmail.com. Not a company domain. Not a professional address. Just a numbered Gmail account.

I deleted it.

Two days later, another pitch arrived. Then another. By the end of October, I’d received seven. In the first three weeks of November, I got twenty-three more.

They came from:

Isaac Michael, offering Pinterest and Goodreads strategies

Halfdaytravel, promising TikTok features at 1:28 in the morning

Pratibha Malav, with a price list for paid reviews across multiple platforms

Janet, pitching websites and cinematic trailers

Someone claiming to be “Dr. Sandra Maria Anderson” using the email address abbyamazonalirah@gmail.com

Some offered video production, others social media management, still others Amazon optimization or Google indexing services. They all shared generic Gmail addresses, vague promises of increased visibility, and an understanding that I was anxious about my books finding readers.

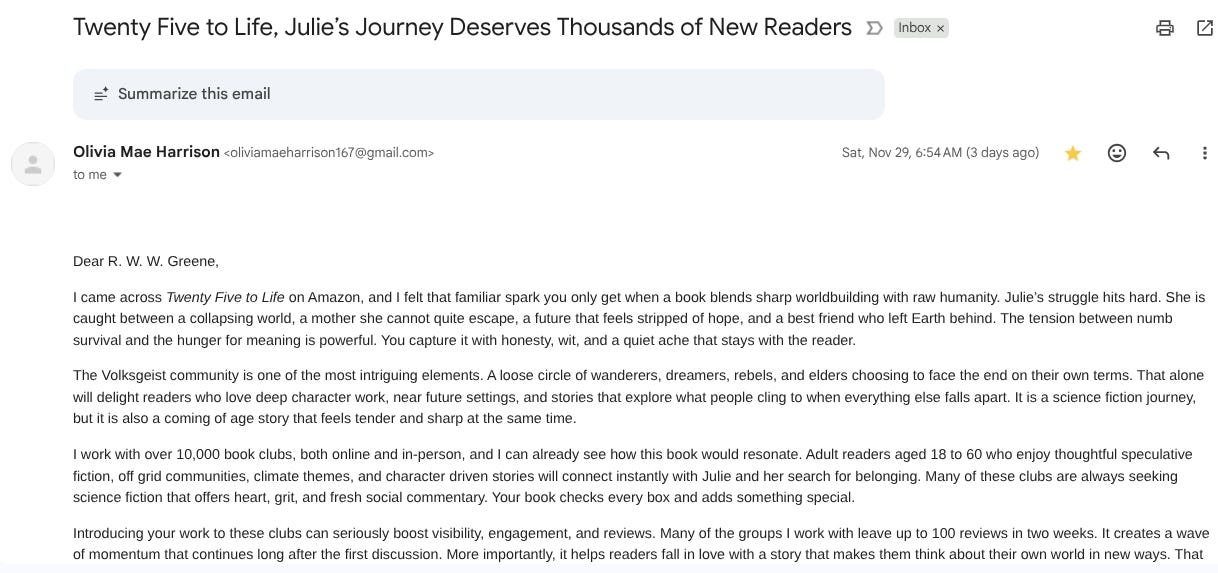

They were 100-percent right about the anxiety, and that’s what makes them dangerous. The economics of traditional publishing are brutal right now, especially for mid-list (and lower) writers.

My actual royalties per book sold (assuming they’ve earned out and I get, ya know, actual royalties):

Ebook: roughly $0.25-0.40

Print book: roughly $0.65-1.00

Audiobook: roughly $1.30-5.00 (depending on format and territory)

If someone charges me $500 for marketing services, I’d need to sell as many as 2,000 additional copies just to break even. Publishers have PR teams, media contacts, co-op placement deals with retailers, and marketing budgets. If Angry Robot, with all those resources, couldn’t get my book onto certain Pinterest boards or Goodreads lists, what makes a freelancer with a Gmail account believe their strategy will work?

The truth is, they don’t believe it will. They believe I might believe it will.

Books ARE harder to discover than they used to be. Algorithms DO matter. Readers ARE out there, somewhere, not finding my work. And, when the next pitch arrives—probably tomorrow or right now—some part of me will wonder: what if?

To understand why these scams are proliferating, look at what’s happening to the industry. More books are being published than ever before (self-publishing explosion plus traditional publishers desperate for revenue), while readership is declining (fewer readers, less reading time, more competition from other media). The result is the average book sells fewer copies than it used to.

Authors are desperate because books aren’t selling, traditional marketing isn’t working, and publishers are offering less support per title. We’re feeling pretty helpless about our career trajectories, watching sales numbers decline while wondering what we’re doing wrong.

Meanwhile, publishers are desperate because the mid-list is dying, there are fewer breakouts, and they can’t afford to market every title the way they used to. They tell authors there’s nothing more they can do, leaving us to wonder if we should be doing something ourselves.

Scammers see opportunity in this desperation. There are more anxious authors than ever before, each one a potential customer. The market is growing (more books = more targets) while competition for attention intensifies. It’s the perfect environment to scale up operations using AI and automation.

That’s why the Summer and Fall of 2025 saw an explosion of these pitches. Summer sales numbers were bad across the industry. Publishers quietly told authors they weren’t picking up next options. Industry articles about the “publishing crisis” circulated widely. The anxiety peaked just as the Q4 season began, and the scammers launched coordinated campaigns targeting authors most likely to be feeling desperate.

In recent articles, Victoria Strauss, co-founder of Writer Beware (the industry watchdog that protects authors from scams, sponsored by Science Fiction & Fantasy Writers Association), has confirmed what I was experiencing wasn’t isolated. She’s been tracking the same wave since June 2025, tracing it to operations in Nigeria using AI to generate personalized pitches at scale. The scams, she wrote, had ramped up faster than any fraud in her decades of experience.

Five, count-em, five book marketing pitches in my inbox. One had arrived at 1:22am while I slept, from someone called “Green Link” promising to feature my book in “active reading communities” through “real organic [Hence the Green? Or am I the Greene?] no ads, just real engagement.” Another came at 9:48am from Sylvester Josh, offering 3D cinematic book trailers. By afternoon, I’d been pitched TikTok features, paid reviews that violated Amazon’s policies, and Amazon optimization services for problems I didn’t have.

A sixth pitch arrived that day but was caught by Gmail’s spam filter—someone claiming to be “Dr. Sandra Maria Anderson” using an email address that didn’t match the name at all.

Nov. 3 was a preview. Over the next three weeks, the pitches would arrive almost daily, sometimes multiple times per day, from senders with names like Mercy Goldcrown (when plain Gold isn’t enough), Naphy Expertt, Ophelia, Bella, Emmanuel, Evelyn, and KAMBIO.

They offered every service imaginable. The prices ranged from $20 to “contact me for [a] quote.” They all claimed to have “real readers,” “active communities,” and “organic engagement.” None provided portfolios, case studies, or verifiable results.

Gmail’s SPAM filter had been fighting for me, catching roughly two out of every three pitches. But that still meant dozens were getting through.

Between October 18 and November 20—just thirty-three days—I documented at least fifty-one pitches. The real number was probably higher. Some I’d deleted without recording. Some had been auto-deleted from spam after thirty days. Some I’d forgotten about before I started keeping systematic track.

I wasn’t being marketed to. I was being carpet-bombed.

A Note on Self-Published Authors

Self-published authors face an even more intense version of this siege. With higher per-book royalties (often $2-7 per ebook versus my $0.25-0.40) and direct control over their Amazon pages, they’re more tempting targets—and the math looks just plausible enough to be dangerous. “If I make $3 per book and sell 200 extra copies, that’s $600!” But they still need to sell those 200 ADDITIONAL copies directly attributable to the service, and fake Pinterest boards don’t work any better for self-pub than they do for traditional publishing.

Self-pub authors are also more vulnerable because they’re responsible for everything: cover design, formatting, distribution, marketing. When someone offers to handle “just the marketing part,” it’s tempting. They have no publisher to shield them, no agent to offer advice, no industry contacts to warn them away.

Victoria Strauss (Writer Beware) has noted that earlier waves of publishing scams—from the Philippines and Pakistan—focused almost exclusively on self-published authors. The Nigerian operations are different: they target everyone with a published book, regardless of how it got there.

On Oct. 28, someone named Isaac Michael sent me seven messages in a single day, each one arriving within hours despite my repeated, polite “no thank you” responses. He’d promised to optimize my “visibility window”—I had exactly sixty days before the algorithm reset, he claimed. He’d already mapped the strategy: 12 Pinterest boards, 8 Goodreads lists, full sequencing. He cited specific boards: “Retro Sci-Fi Worlds” with 18K+ saves, “Alien First Contact Stories” with 12K+ saves.

His response speed suggested AI assistance. The pressure tactics suggested desperation. The numbered Gmail account (isaacmichael0181@gmail.com) suggested the same operation I was seeing everywhere else. (He also tried to convince me to spend all this money on the second book of a duology, which made no fucking sense.)

I finally ignored Isaac. But on Nov. 13, the same playbook returned with a new sender.

“Hey Robert,” Veronica Emmanuel began, “I’ve been digging into Six Plays and noticed a couple of big missed opportunities.”

She claimed the book was missing opportunities on Pinterest and Goodreads. She’d identified specific boards and lists where the work should appear. She had the complete strategy ready: sequencing, timing, a plan to sync both algorithms within a critical sixty-day window.

It was detailed and professional-sounding. The same service Isaac had pitched, delivered by someone new!

Except for one problem: I have never written a book called Six Plays. Six Plays is a collection of works by Robert Greene—the Elizabethan playwright who died in 1592.

Veronica Emmanuel, with her detailed Pinterest strategies and algorithm insights and carefully mapped visibility plans, had confused me with a man who’d been dead for 433 years.

Seven days later, she followed up. Had I reviewed her strategy for Six Plays? The timing was critical. The algorithm window was closing.

I decided to test the system.

“Hi Veronica,” I replied. “I’m very interested in your strategy for Six Plays. Just one question: which edition are you working with? The 1599 quarto or the 1861 Dyce compilation? Also, do you think Pinterest is the right platform for Renaissance drama, or should we focus on the Globe Theatre’s social media? Thanks, Robert Greene (the science fiction author, not the dead playwright).”

Her response arrived within hours.

She’d chosen the 1861 Dyce compilation, she explained, for its “cohesive editorial structure” that made it easier to build marketing materials. Pinterest wasn’t conventional for Renaissance drama, but it worked through “visual discovery and mood-based storytelling.” She cited specific boards: “Renaissance Theatre Moodboards” with 8-12K monthly saves, “Historical Drama Visuals” with 10K saves, “Shakespeare-Inspired Imagery” with 7-9K saves.

The response was sophisticated, detailed, confident. It explained audience overlap with “dark academia” aesthetics, compared Pinterest’s algorithmic distribution to the Globe Theatre’s narrower reach, and discussed how to bridge “literary integrity and modern reader discovery.”

It was impressive. It was also completely insane.

“Thanks for your questions,” she’d written, “and noted, the sci-fi author, not the Renaissance playwright!” Then she’d spent three paragraphs explaining her marketing strategy for the Renaissance play collection anyway.

I gave her one more chance. “Veronica, I have never written a book called Six Plays. That’s a collection by an Elizabethan playwright who died in 1592. I yet live and I write science fiction. Can you explain what’s happening here?”

Two and a half days later, she apologized. There had been a mixup, she explained. She worked with “a large number of authors each week” in batches, and my name had come through in a group where someone was requesting analysis of the public-domain Six Plays collection. “The system flagged your name as connected to that title,” and she’d mistakenly continued the conversation.

The system.

She claimed to be “familiar with my traditionally published novels,” though she never named them. She offered to “regroup and talk about my actual catalog.” The sale was still on, if I was interested.

But I’d learned what I needed to know. This wasn’t a person carefully researching authors and crafting custom strategies. This was an operation using AI to process names in batches, generating confident pitches, powered by systems that couldn’t tell the difference between a living science-fiction writer and a playwright who’d been dead for four centuries.

And when caught in an impossible error, the response was: apologize, blame the system, pivot to the actual product.

Veronica followed up twice more in the next twenty-four hours, offering generic “multi-platform frameworks” and “audience targeting strategies.” She still never named my books. She claimed to have identified “time-sensitive opportunities” in my catalog and put together a breakdown of where I was “missing discoverability.”

While I was fencing with Veronica, another scammer was trying a different approach: pretending to be someone real.

On Nov. 2, I got an email from “Judy Leigh” writing from the address faithexpert92@gmail.com.

“Hi, I’m Judy, an author based in the UK. I published my book not too long ago, and it has recently started performing very well and it’s currently one of the top-selling books on Amazon in its category.”

She wanted to connect with fellow authors to share strategies. Would I be interested in learning how she was growing her readership and sales?

I might have been flattered to hear from such a fancy person, but the email address was suspicious: “faithexpert92” had nothing to do with “Judy Leigh.”

Then on November 18, “Judy Leigh” followed up. She was checking in to see if I’d received her first message about book marketing strategies. Would I like to connect?

Something made me Google the name.

There IS a Judy Leigh. She’s a legitimate UK author published by Boldwood Books who has sold over a million copies. She writes uplifting contemporary fiction celebrating friendship and second chances. She also writes historical novels under the pseudonym Elena Collins. Faithexpert92 was even using Judy Leigh’s headshot as a profile picture.

But I was highly suspicious that the person emailing me wasn’t her.

I decided to test this one too. I lied apologetically—sorry for the delay, your message went to spam. Then I asked a simple question: “How did you find out about me?”

Four hours later, “Judy” responded with “Hi Greene, Thank you so much for getting back to me!” Instagram had suggested my page, she claimed. Since we were both authors, my work had caught her attention. She asked about my sales and what marketing strategies I’d implemented—standard sales qualification questions to assess whether I was desperate enough to buy. I played along, positioning myself as the perfect target (which I am): traditionally published, relying on my publisher for marketing, passive about promotion, seemingly naive.

“Ha! Your email address threw me off a bit. I thought you might be a scammer. It’s nice to know you are a real person! My publisher does the lion’s share of the marketing chores. I just write the things!”

The next morning, “Judy” delivered her pitch.

She’d “recently discovered” that Medium was running an “End-of-Year Book Feature Promotion” selecting 200-300 books for automated daily promotion. The window was closing soon. She’d tried it herself and seen “a noticeable boost.”

There was one detail: she worked with “someone in the United States who specializes in writing book-related blog posts on Medium.” They’d handled hers. Would I like the contact?

This was the pattern Victoria Strauss had documented: scammer builds trust, offers helpful advice, then refers to a third party for payment. The money routes through Upwork or Fiverr to an “assistant” in Nigeria. The service either doesn’t materialize or delivers something worthless.

I’d also seen this exact pitch before. Three days earlier, someone called “Mercy Goldcrown” had offered me a “$30 promo slot for a short, polished announcement blog” on Medium, claiming it was perfect for the “Ember season.”

Medium doesn’t run “End-of-Year Book Feature Promotions.” The entire premise was fabricated.

I messaged the real Judy Leigh through Facebook, then emailed her publisher Boldwood Books to alert them that someone might be using her identity to scam other authors. Neither responded.

Finally, I posted a warning to the real Judy’s blog, explaining that someone was impersonating her using an email address with her headshot. She let the comment go through the moderation process and responded with a “Like.” No comment. No outrage. No warning to her readers. Just acknowledgement. (Did she know? Is she tired of hearing about it? I’ve no way to tell!)

The fake Judy Leigh, meanwhile, was still waiting for my response about the “expert” who could help get my book selected for Medium’s non-existent promotion.

On Nov. 25, I told her the truth:

“’Judy’: Medium doesn’t run ‘End-of-Year Book Feature Promotions.’ I know because I checked. I also checked with the real Judy Leigh and her publisher to see if you were she. Outlook not so good. So, I’ve been documenting this entire exchange for an investigative article about book marketing scams. Would you like to comment?”

She never responded.

Addendum: Writer Ann Leckie, who I follow on BlueSky, recently reported someone was using her name to run a similar scam.

The cruelest part isn’t that the scammers are lying about their services. Scammers gotta scam. It’s that the problem they’re claiming to solve is real. Books ARE harder to discover. Algorithms DO matter. The gap between authors and readers IS widening. Traditional marketing IS failing.

And the scammers are exploiting this with sophisticated psychological hooks:

They identify real problems (discoverability, algorithm changes, market saturation)

They offer specific solutions (Pinterest boards with exact save counts, Goodreads lists with member numbers)

They create urgency (algorithm windows closing, seasonal opportunities, competitive selection processes)

They minimize barriers (low prices, “no time required on your end,” pre-built strategies)

They exploit isolation (authors working alone, desperate for answers, willing to try anything)

These services can’t fix anything, but there’s always someone willing to risk money on a map to buried treasure.

As I finished writing this last week, three more pitches arrived.

One offered TikTok features. One promised Amazon visibility optimization. One claimed to run a “curated community of 5,000+ passionate readers” who will review my book for small tips of $25-30 each, minimum 30 reviewers required. Thirty times thirty is -- what? -- $900? I could foot that.

Because what if this one is different?

What if I’m wrong? What if shelling out a grand is all I need to get my writing career really going?

What if I’m the fool for not even trying?

Man, I want to believe I can change my stars with a simple cash infusion! That little inner whisper is what they’re counting on: that the gap between the work we’ve done and the readers who haven’t found it will always be wide enough for hope to slip through. That desperation can overwhelm mathematics.

Tomorrow, another author will receive their first pitch. They’ll wonder if maybe, just maybe, this could be the thing that works. Somewhere, a system will flag their name, generate a personalized email, and send it from a numbered Gmail account.

The algorithm never sleeps. The pitches never stop. Here’s one now.

And now.

Now.

Note: If you’re an author receiving similar pitches, Victoria Strauss’s Writer Beware blog (writerbeware.blog) maintains updated information about current scams. The Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers Association (SFWA) also provides resources for identifying and reporting fraud. Most importantly: talk to other authors. The community is our best defense.

Rob Greene (R.W.W. Greene) is the author of several science-fiction novels published by Angry Robot Books. His newsletter “twenty-first-century blues” examines culture, technology, art, and the systems that shape our lives. In writing this article, Greene used Claude (Anthropic) as a tool for structure, data organization, and feedback.

![[Image: Drowning meme with “Mid-List Authors” underwater, “Debuts and Best-Bestsellers” and “Traditional Publishing” on the surface, “Everyone Else” as skeleton at the bottom] [Image: Drowning meme with “Mid-List Authors” underwater, “Debuts and Best-Bestsellers” and “Traditional Publishing” on the surface, “Everyone Else” as skeleton at the bottom]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!myN1!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fa6785bdf-afea-4080-a394-b396cacbb926_500x659.jpeg)