After I quit my job this past May, I wanted to spend some of my time off writing book reports. How odd, you might say. Who quits their job so they can sit at home writing book reports? Shouldn’t I have written enough of those in school?

Initially, I’d planned only to read, not write about, the books on my reading list. But I kept thinking about how little I retained just months after finishing something. The main ideas and themes, I could remember well, but the finer details were often lost to me. What’s the point of reading a ton of nonfiction if you’re just going to forget all the important stuff later? I thought writing book reports could be a way not just to collect and clarify my thinking, but also to serve as a trusty reference to look back on. This way, years from now, instead of agonizing over how my memory’s gone to shit while trying to remember some specific points from a book, I can just read my book report.

“Congress shall make no law…abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press”

For something that sounds so simple, the First Amendment has been front and center in the news an awful lot lately: Trump getting booted from Twitter, calls for Joe Rogan’s podcast to be removed from Spotify, Elon Musk’s bid to buy Twitter, the Department of Homeland Security’s quick fizzle of the Disinformation Governance Board, Julian Assange’s indictment under the Espionage Act, and more.

I thought I knew what free speech and the First Amendment meant, but I wasn’t so sure anymore after seeing these issues in the news all the time. To get educated, I thought it best to understand the legal history of the First Amendment. Specifically, I wanted to understand how the country’s Supreme Court justices have voted on First Amendment issues over time. My hunch is that the Court’s opinions on free speech issues, as well as the larger historical context in which they were written, likely offer clues on how we should be thinking about current free speech issues. To that end, my goal isn’t to be prescriptive. I’m not trying to advocate one way or another on First Amendment issues. Instead, I want to be descriptive. I’m interested in describing how the Supreme Court has opined on the First Amendment over the last 200+ years, and how the meaning of the First Amendment has evolved due to legal precedent.

Lucky for me, Anthony Lewis’s Make No Law does exactly that. It uses the Supreme Court case New York Times Co. v. Sullivan — a landmark case on press freedoms that Justice Clarence Thomas recently said he wants to “revisit” — as a backdrop for tracing the legal history of the First Amendment.

On March 29, 1960, the “Committee to Defend Martin Luther King and the Struggle for Freedom in the South” published an advertisement in the New York Times called “Heed Their Rising Voices” The ad was sharply critical of police response to civil rights demonstrations taking place throughout the South (particularly, Montgomery, Alabama) and sought to raise money for MLK’s defense fund. The advertisement contained number of statements that were inaccurate1, the most serious error being that the dining hall described in the advertisement wasn’t actually “padlocked in an attempt to starve [the students] into submission.”

L.B. Sullivan, a Montgomery city commissioner and in charge of the police, took offense to the ad. Though the ad never mentioned Sullivan (or anyone in law enforcement specifically), Sullivan felt the ad was directed at him and he wrote to the Times demanding a retraction. The law firm representing the Times replied: “We…are somewhat puzzled as to how you think the statements [in the ad] reflect on you.”

Sullivan never got around to replying back to the Times’ lawyers. Instead, he sued them for libel2 and the case was tried in Montgomery circuit court.

Why did Sullivan take offense to the ad, especially since any reasonable person would agree that the ad didn’t refer to him, and so had no effect on his reputation? I’m inclined to think the answer isn’t simply that Sullivan was the world’s most sensitive person (though maybe he was a little sensitive. Who’s to say, really). The actual answer is because of racism. Southerners were indignant with how the North portrayed the Southern Way of Life. Following the trial, Montgomery’s evening paper wrote that the verdict “could have the effect of causing reckless publishers of the North…”3 to think twice before publishing something negative about the South. Indeed, this was a case of using libel as a tool to suppress criticism of the South — quite literally a means of silencing the press. Lewis elaborates4:

Commissioner Sullivan’s real target was the role of the American press as an agent of democratic change. He and other Southern officials who had sued the Times for libel were trying to choke off a process that was educating the country about the nature of racism and was affecting political attitudes on that issue. Thus in the broadest sense the libel suits were a challenge to the principles of the First Amendment.

The trial itself took place over three days. Under Alabama’s law of libel (at least at the time), any mistakes in the published material, however trivial, loses the defense of truth. This was unfortunate for the Times, because they conceded that there’d been some factual errors in the ad. As a result, the jury was instructed to decide only two things: (1) if the Times published the ad, and (2) whether the ad was about Commissioner Sullivan. It took them a couple hours to decide, and they ruled in favor of Sullivan, awarding him $500,000 in damages.

The Times appealed to the Supreme Court of Alabama only to have them rule again in favor of Sullivan. “The First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution does not protect libelous publications,” they said.

Eventually, the Supreme Court of the United States agreed to hear the Sullivan case. But before getting there, let’s take a detour. How was the Court thinking about free speech at the time, and how had these ideas been tested before the Sullivan case?

I had always naively assumed that there was widespread consensus on the meaning of the First Amendment since its inception. But this isn’t the case at all. Lewis explains in an interview with C-SPAN from 1991:

We tend to assume that the First Amendment…ever since that was written into the American Constitution 200 years ago, December 1791, ever since then we've been free. But it's not like that. Not at all…it really wasn't until very recently that the courts, and the Supreme Court particularly, gave concrete meaning to those words and really put back into the First Amendment what James Madison, its principal author, thought was there. For most of its history the amendment was not enforced, and no person who made a claim of a right to free speech under the First Amendment really won a case in the Supreme Court until, I'd say, 1930. That's pretty late.

The story of the First Amendment is a story of speaking out against political figures. It’s a story where, time and again, free speech has been in tension with two things: (1) reputation and (2) public welfare. That story begins in 1798, when Congress passed the Sedition Act, which made it a crime to criticize the government.

When the First Amendment was written in 1791, the prevailing notion of free speech was rooted in English Common Law, popularized by English jurist Sir William Blackstone: freedom only from prior restraint. That means you can publish whatever you like, but if you say something scandalous, you’ll be liable for punishment after the fact. This was a departure from the system of “prior restraints,” a form of pre-publication censorship introduced in 16th century England where all published material had to be approved by the Crown before printing. Blackstone argued against prior restraints, but he still thought people should be punished if they said things that were “dangerous” or “offensive.”

Blackstone’s view was how the Federalist party, led by President John Adams, understood free speech when the Sedition Act passed in 1798. The US was on the heels of war with France, and the Federalists used the all-too-familiar politics of fear as a weapon to silence their critics in the opposition party, the Democratic-Republicans (or Republicans, for short). To the Federalists, political criticism counted as “dangerous” or “offensive.”

In what became known as the Madison Report, James Madison expressed both his vociferous opposition to the Sedition Act and articulated a defense of free speech that made its way into the Sullivan case. Madison’s contention was that in our country, the citizens are sovereign, not the government. A citizen’s criticism of government is what gives government legitimacy, so citizens can’t be punished for criticizing politicians; they work for us, not the other way around.

Though many were prosecuted under the Sedition Act, the act itself was never tried in the Supreme Court. It expired in 1801 due to a clause the Republicans managed to include in the legislation before it passed. After the Sedition Act, the First Amendment wasn’t really tested again until World War I.

In 1917, Congress passed the Espionage Act, once again making it a crime to criticize the government. It was a rehash of the Sedition Act. According to Lewis5, the “most innocuous criticism of government policy or discussions of pacifism were found to be violations of the Espionage Act.” Hundreds were prosecuted for resisting the draft, criticizing military intervention, or spreading socialism. This time, many cases did make it to the Supreme Court, but the majority of the Court still held a Blackstonian view of speech.

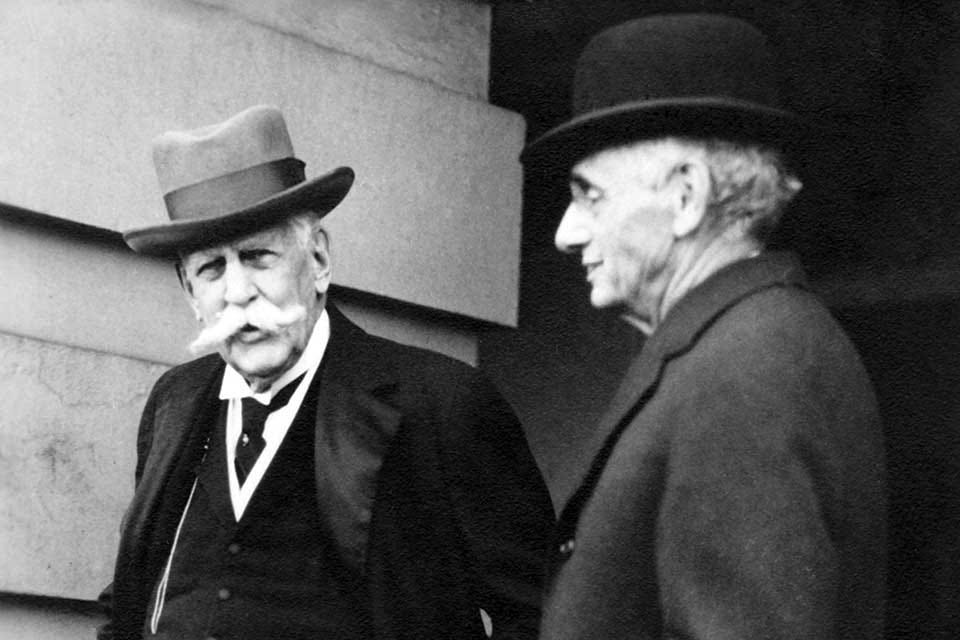

It was a series of dissenting opinions from Justices Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. and Louis Brandeis that slowly convinced the nation of the Madisonian view of speech. It started with Holmes’ dissent, joined by Brandeis, in Abrams v. United States (1919), where refugees from Czarist Russia were prosecuted for distributing leaflets critiquing US military intervention in Russia. Holmes’ dissent was memorable for three reasons. He argued that (1) there must be a “clear and imminent danger” to warrant limiting speech6; (2) that truth is best tested in a marketplace of ideas; and (3) seditious libel (i.e., criminalizing speech critical of government) is a violation of the First Amendment7.

But what exactly constitutes “clear and imminent”? How do we know when danger is “clear and imminent” enough to quash speech? Brandeis offered clarity in his opinion in Whitney v. California (1927): “only an emergency can justify repression;” only when serious evil is “so imminent that it may befall before there is opportunity for full discussion.”

Ok, so the Court finally offered a test to determine when speech was constitutionally protected. But what about prior restraints? Did the majority of the Court still hold the Blackstonian view?

It wasn’t until 1931 that the Court heard its first case on press freedom in Near v. Minnesota, and it was in Near that the Court finally established that prior restraints were suspect under US law. Near was a defamation case, but the Court ultimately punted on the question of whether defamation was constitutionally protected. Instead, the Court only ruled that the government couldn’t stop publication in advance, except in very narrow circumstances (wartime, the exposure of military secrets, etc.).

So what does the Court have to say about defamation? Is libel within the purview of the First Amendment? And what if the defamatory remarks are mostly false or contain misinformation? To answer that, let’s jump back to the Sullivan case.

Herbert Wechsler was the attorney for the Times when the case reached the Supreme Court in 1964. Wechsler’s argument to the Court was predicated on Madison’s opposition to the Sedition Act — “that defamation is intrinsic in the criticism of public officials, the discussion of public affairs.”8 Wechsler also took pains to sidestep the debate about the “intention” of the First Amendment. “Whatever the intention in 1791…the protest against the Sedition Act between 1798 and 1800 produced a consensus that under the First Amendment Americans could not be punished for criticizing public officials.”9

While Wechsler’s argument was that citizens should have full license to criticize government — and that even false political speech shouldn’t be punished — he felt that might be a tough sell to the Court. What if someone was spreading deliberate lies in an attempt to ruin a politician’s reputation? How might that politician redeem their name?

To this end, Wechsler proposed the “actual malice” test. Not to be confused with the dictionary definition, “actual malice” in this context means “knowing or reckless falsehood.”

How did the “actual malice” test square with the fact that there were a number of factual errors in the advertisement? After all, this was part of the plaintiff’s two-pronged argument to the Court: that the Times lose their First Amendment protection because of some false statements in the advertisement (their other argument being that the ad referred to and damaged the reputation of Commissioner Sullivan and the city of Montgomery).

The Court decided unanimously in favor of the Times. In his opinion, Justice William Brennan made four points in favor of reversing the judgment:

The First Amendment is characterized by a “profound national commitment to the principle that debate on public issues should be uninhibited…and wide-open…it may well include vehement, caustic, and sometimes unpleasantly sharp attacks on government and public officials.”10

Defamatory words aimed at officials is constitutionally protected speech. “Injury to official reputation affords no more warrant for repressing speech that would otherwise be free than does factual error.”11

There is no test for truth under the First Amendment — “erroneous statement is inevitable in free debate,”12 and furthermore, “a rule compelling the critic of official conduct to guarantee the truth of all his factual assertions…leads to…‘self-censorship’…Would-be critics of official conduct may be deterred from voicing their criticism, even though it is believed to be true and even though it is in fact true, because of doubt whether it can be proved in court or fear of the expense of having to do so.”13 In other words, misinformation alone isn’t sufficient to forfeit constitutional protection. “Reckless or intentional falsehood” must be proven.

The Times advertisement does not meet the “actual malice” test. The advertisement was not published with reckless disregard nor did the Times intentionally publish false information in the ad. The Times relied on the reputation of the signers of the advertisement and made a good-faith effort to ask Sullivan how he thought the advertisement referred to him. At best, the advertisement was negligent, not reckless.14

The Court also found that the advertisement was not “of or concerning” Commissioner Sullivan (big surprise).

The Sullivan case was about libel of public officials, but what about libel against private citizens? Is that also protected?

The answer is: it’s complicated. The lines between “public” and “private” blurred in the cases following Sullivan, and the Court was divided on how to adjudicate between the two.

Justice Brennan proposed that actually it shouldn’t matter if the person is a public official or a private citizen, but rather whether the subject matter is “of public or general interest.”15 We’re all in the public sphere to some extent, he argued. This view drew criticism from other justices, notably Justice Thurgood Marshall, who argued that “society’s interest [is] in protecting private individuals from being thrust into the public eye.”16 What was needed was to strike a delicate balance between free speech and reputation.

Justice Lewis Powell laid the groundwork for this balance in Gertz v. Welch (1974), which Lewis summarizes17:

In sum, the cases on the public-private issue left us with a complicated set of constitutional rules. If you are a private person, out of public eye, and someone publishes a false and damaging statement about you on a subject of no general interest, you can recover libel damages in any way that state law provides; the Constitution does not apply to your case. If you are a private citizen attacked on a matter of public concern…you must meet the requirements of state law and also, under the First Amendment, prove that a false statement was made about you at least negligently. If you are a public figure or a public official, you must meet the constitutional test of showing knowing or reckless publication of a falsehood. It is all much less straightforward…than it seemed when New York Times v. Sullivan was decided in 1964.

Ok, but how do we delineate between “negligence” and “knowing or reckless falsehood?” Lewis explains18:

The duty to check is the difference between the two constitutional standards. An editor is negligent if he publishes a story without checking and it turns out to be false. He is reckless only if he is put on notice of likely falsity and still proceeds to publish.

And finally, how exactly do we know when something is of “public concern.” Some things are very clearly of public interest, other things very clearly not. But some things are murky, where to draw the line? Frankly, I’m not entirely sure. Perhaps it’s for the courts to decide.

These rules are helpful, and they do shed some light on how to think about speech issues. But I’m struck by what these rules reveal about law’s ever changing nature. “We live under a written Constitution, and we rely on its unchanging character to give stability to our turbulent society,” Lewis writes. “But the Constitution continues to have meaning and life only because judges apply it in fresh ways to challenges unforeseen by its creators.19”

Throughout the First Amendment’s story, the justices wrestled with balancing history against the prominent political theories of their time. With each decision, the justices added a new layer to the meaning of the First Amendment. They didn’t view the law as some abstract thing that they had to expertly interpret. They were instead “guided by their sense of society: its traditions, its needs, its changing character.”20 Such is the “complex course of decision in the decades after New York Times v. Sullivan…as the Supreme Court struggled to make libel law conform to the commands that there be ‘no law…abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press.’”21