Welcome to Second Story, a newsletter for people who love old houses and prewar floorplans. If you don’t subscribe, sign up below! Or if you like what you read, please tap the heart to boost this post on Substack! - Robert

“54-ROOM APARTMENT IN FIFTH AVENUE HOUSE FOUND VACANT; LITTLE HOPE OF RENTING IT,” read a New York Times headline in 1944. The penthouse non grata was none other than Marjorie Merriweather Post’s legendary triplex at 1107 Fifth Avenue, the largest apartment in NYC history. “The oversize rooms where nearly a score of servants formerly scurried about are now dark and silent.”

“Times have changed, you know,” the brokers commented to The Times.

Nobody would live in that wild apartment again. Just a few years later, Marjorie’s mansion in the sky, along with the rest of the the large apartments ranging from 15 to 21 rooms at 1107 Fifth Avenue, would be cut up into suites of two to six rooms to attract midcentury tenants seeking a simpler lifestyle.

Marjorie’s 54 rooms on Fifth Ave might be an extreme case, but 1107 wasn’t the only building to obliterate its sprawling layouts for the sake of marketability. Throughout the 1940s and ‘50s, at a time when new buildings were offering smaller, less formal apartments—the dawn of the postwar apartment—many earlier buildings had their grand, multi-room layouts shorn into streamlined residences for a clientele that no longer lived so formally, even for those who could afford it. This wave of development, honestly re-development, sounded the death knell of the prewar apartment across New York City.

Interestingly, the shift away from prewar layouts also began pre-war. The New York Times ran a small item in 1930 where architect Morris Witson advocated for the modernization of the many “old” buildings across the city. These buildings may have been just a decade or two old, but their 5-to-10 room layouts were no longer drawing tenants. Morris urged for redevelopment into apartments of two to three rooms. He argued that not only would this create jobs for those who need them, but it would also meet the “crying need” for more manageably sized apartments that was steadily growing among city dwellers.

That need would become the presiding influence over apartment development. During Manhattan’s heyday of apartment building in the 1920s, 16% of the 83,500 apartments built had at least six rooms. In the years following the war, that would fall to around 1% of new apartments as tastes shifted toward homes with fewer rooms, more open layouts, and easily accessible kitchens that didn’t necessarily assume live-in staff.

By 1939, it seemed like every prewar apartment was getting remodeled to keep up with the shifting real estate landscape, and enemy number one were the especially large penthouse or custom apartments.

“In keeping with the present trend, several large apartments in cooperative buildings under the management of Douglas L. Elliman & Co. have been cut up into smaller suites,” reported a Times article in October of that year, which called out a 21-room penthouse at 455 East 57th Street, which became three apartments, and an 18-room duplex at 66 East 79th which became four different apartments. A representative of Douglas Elliman explained that the well-to-do prefer these layouts as they’re easier to maintain when flitting in and out of the city.

And then there’s “the servant problem.” Let us not forget that these vast prewar apartments not only accommodated but relied on sometimes substantial cohorts of live-in staff to run and operate as intended. By the early-mid 20th century, expenses related to domestic staff were rising while fewer and fewer people were entering that line of work with its long hours, grueling duties, and low pay. “The servant problem,” as it became known, only became more acute as the decades rolled on, and these large apartments, some of which had 30%-50% of their square footage devoted to staff quarters, became obsolete.

Owners of these buildings, whether it was a co-op or a rental, remodeled in the hopes that apartments would sell or rent quickly—and it worked. Another item in The Times profiled a building on West 157th Street that became fully rented and more financially successful than ever after its six and seven-room apartments became homes of three and four rooms.

While practically every block in New York has a remodeled prewar building, there are some renovations that are particularly notable. Let’s take a look.

Built in 1909 in the French Renaissance style, Alwyn Court at 180 West 58th Street originally had two 14-room apartments on each floor. Apparently it also had a pretty fabulous 34-room spread, but I cannot find a floorplan for that. The early apartment building was designed to attract tenants used to townhouse living. Its winding layouts had reception rooms, music rooms, and billiard rooms that would not only appeal but feel familiar.

“Many persons remember the old Alwyn Court built in 1908 as the last word in apartment luxury,” said the 1939 New York Times article announcing its remodel from 22 apartments to 75 apartments of 3, 4, and 5 rooms. “And recall how this building, structurally sound and desirable from every standpoint, had become obsolete as result of changing standards of metropolitan life.”

Work began in 1938. By 1939, the building was 100% rented.

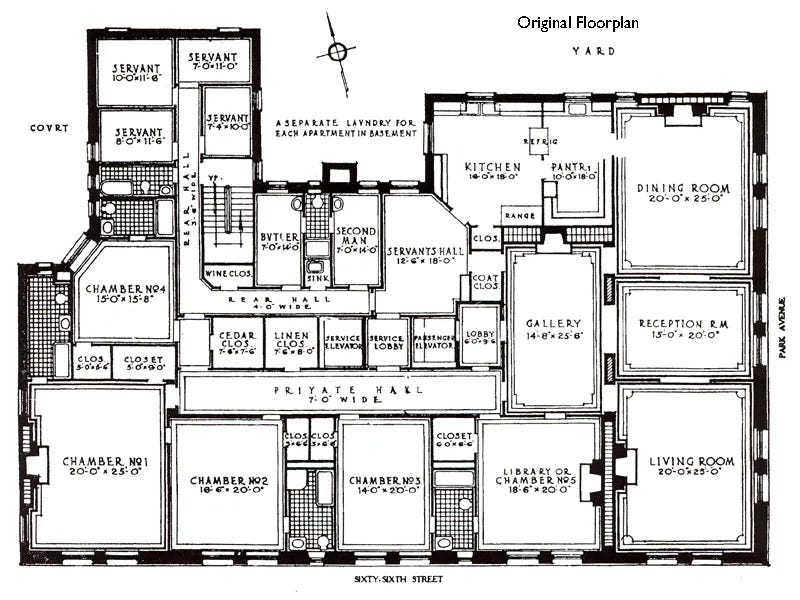

Quite possibly the largest floorplans to be remodeled and broken up, 630 Park Avenue was built in 1917 by J.E.R. Carpenter with impossibly grand, 18-room full-floor apartments. It was remodeled in 1950 to have three apartments per floor.

This is one of my favorite prewar floorplans, full stop. I love the coat closet/passage that leads both to the half bathroom and the staff quarters.

Just look at how the sales brochure, which was printed following the renovation, describes how 630 Park Avenue now offers the best of both worlds: Prewar elements (ceiling heights, proportions, working fireplace) but layouts for “conservative living.”

The designer David Kleinberg once described the apartments at 630 Park Avenue to me as “big little apartments,” and that was spot on. The rooms still retain some of the proportions of the originally gigantic full-floor spreads that were once at 630 Park. Ceilings are lofty, windows are huge, and hallways are wide.

Every so often an apartment will come to the market that has an original room from one of the old apartments intact, like a former library that has been transformed into a living/dining room.

Originally designed by J.E.R. Carpenter with apartments ranging from 11 to 22 rooms—with one absolutely stupendous 30-room apartment on the top floor—907 Fifth Avenue also got remodeled in 1950 to have 50 apartments from 3 to 9 rooms.

There were a few apartments that escaped the 1950 refit: The private apartments of Huguette Clark, who infamously owned three apartments at 907 while living out the last few decades of her life in a Beth Israel hospital room. One of those apartments, the 14-room 12W, sold for $25,500,000 in 2012 following Huguette’s passing.

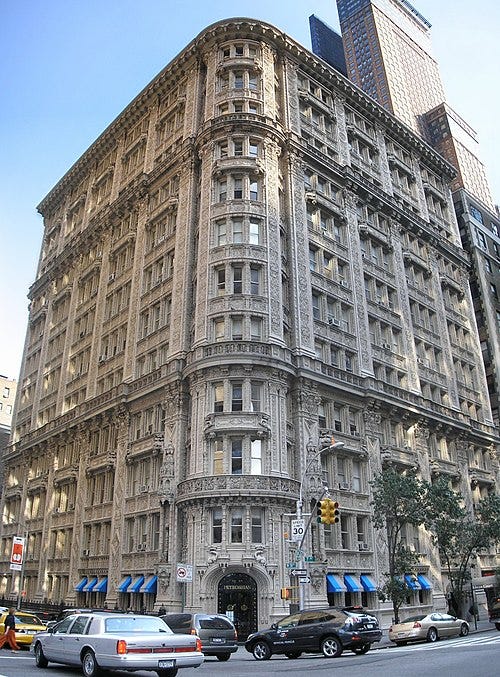

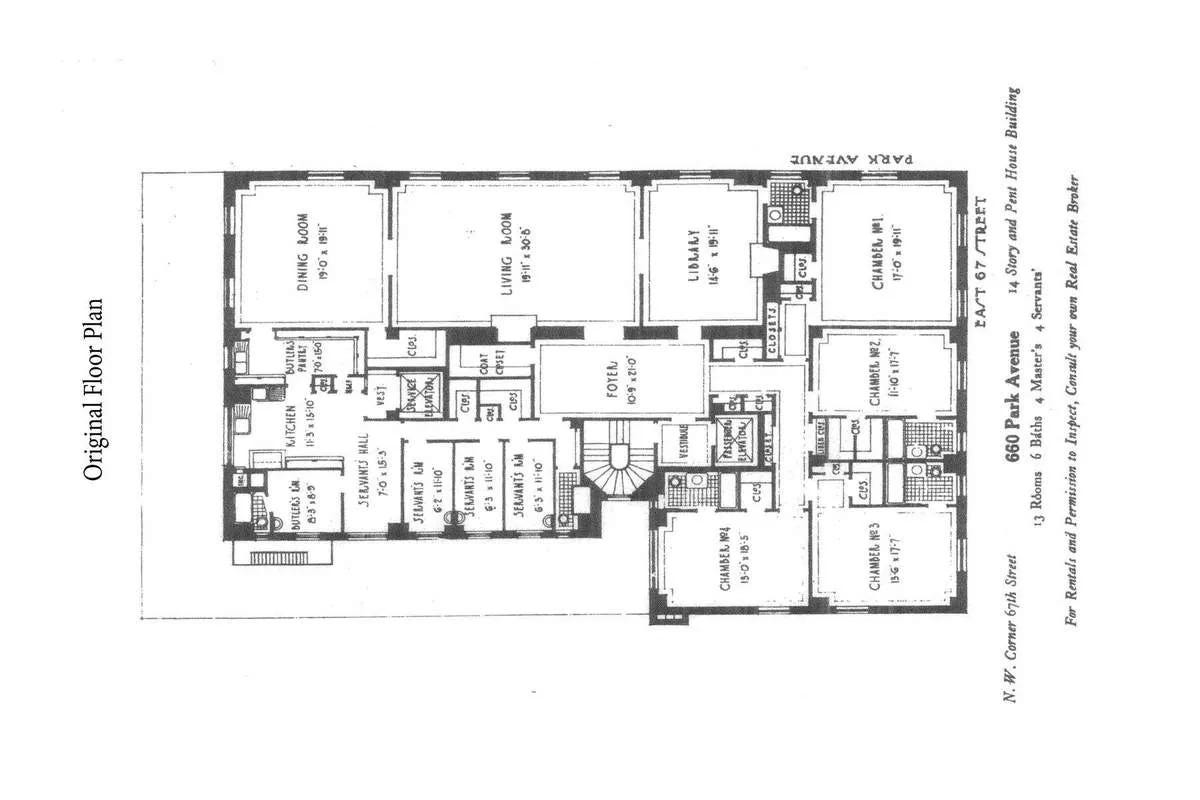

While many (if not most) of the grand prewar buildings were altered in some way over the years, there are a number that have remained unchanged, like 660 Park Avenue, with its full-floor suites and remarkable 34-room maisonette, likely the largest prewar apartment still extant on the Upper East Side, if not all of New York.

Same could be said for 640 Park Avenue—the smaller sister of 630 Park Avenue—and Candela buildings in Lenox Hill like 740, 770, and 778 Park Avenue. I haven’t found a consistent explanation for how some buildings were remodeled while others remained unchanged. As far as I can tell, it wasn’t connected to the building’s status as co-op or rental, and it was not connected to how wealthy the tenants were at the time of the retrofit. If that was the case, then 630 Park Avenue would have survived as originally designed.

But just in case you’re on the hunt for an untouched layout, there are other buildings similar to 907 Fifth that were mostly redeveloped, while a few choice apartments remained intact, likely due to some very stubborn (thankfully so!) tenants.

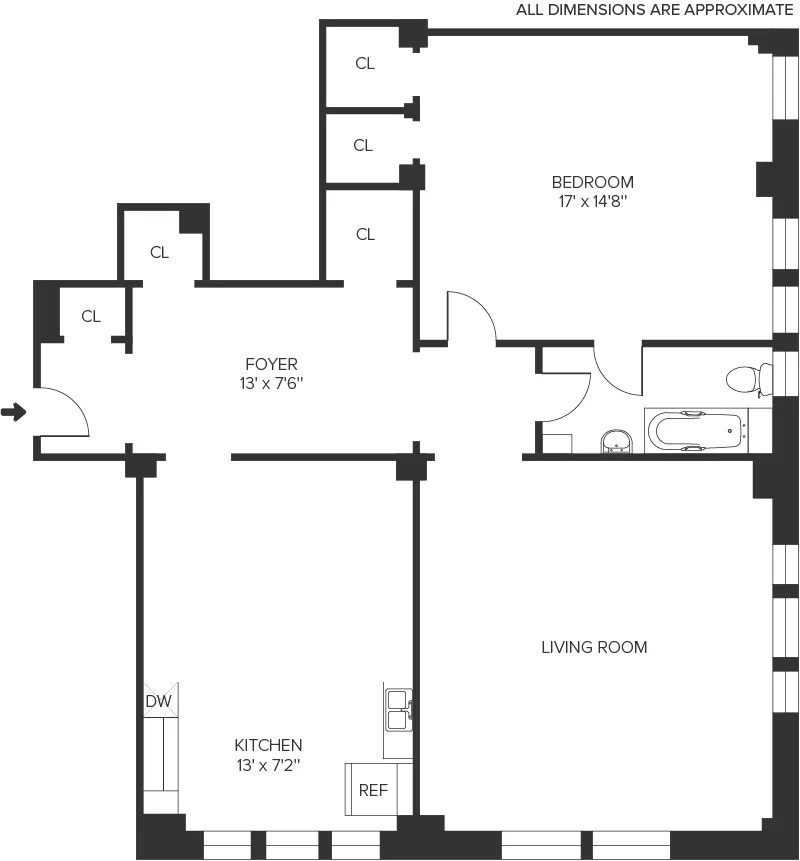

404 Riverside Drive—also known as the filming location for The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel—is one such building, which originally had two apartments per floor. The Maisel Apartment is the N-line, most of which were (what else?) subdivided sometime in the mid-20th century.

A few choice original N-lines still remain (which shouldn’t surprise us at all… The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel was filmed in one of them). They seldom come available on the open market, the most recent public sale was 12N in 2017 for $5.2M, likely because they are highly desired in the building.

The most recent intact N-line to sell was 6N for $3.2M in 2023, which traded off-market between shareholders in the building, but you didn’t hear it from me. I guess it’s not surprising that these architectural rarities are such hot commodities: The lucky buyers clearly know that they’re not just purchasing an apartment—they’re becoming custodians of a remnant of New York’s past.

A FEW MORE THINGS

David Netto found the floorplans for the maisonette at 666 Park Avenue!

I have become weirdly obsessed with Harry’s body wash, which I think is the best drugstore body wash I’ve tried.

Next week, electricians (hopefully) begin rewiring our 200-year-old house in the Finger Lakes. More on that soon, but until then, wish us luck!