Floating-Point Printing and Parsing Can Be Simple And Fast

Russ Cox

January 19, 2026

research.swtch.com/fp

Posted on Monday, January 19, 2026.

PDF

Russ Cox

January 19, 2026

research.swtch.com/fp

Posted on Monday, January 19, 2026. PDF

Introduction

A floating point number has the form where is called the mantissa and is a signed integer exponent. We like to read numbers scaled by powers of ten, not two, so computers need algorithms to convert binary floating-point to and from decimal text. My 2011 post “Floating Point to Decimal Conversion is Easy” argued that these conversions can be simple as long as you don’t care about them being fast. But I was wrong: fast converters can be simple too, and this post shows how.

The main idea of this post is to implement fast unrounded scaling, which computes an approximation to , often in a single 64-bit multiplication. On that foundation we can build nearly trivial printing and parsing algorithms that run very fast. In fact, the printing algorithms run faster than all other known algorithms, including Dragon4 [30], Grisu3 [23], Errol3 [4], Ryū [2], Ryū Printf [3], Schubfach [12], and Dragonbox [17], and the parsing algorithm runs faster than the Eisel-Lemire algorithm [22]. This post presents both the algorithms and a concrete implementation in Go. I expect some form of this Go code to ship in Go 1.27 (scheduled for August 2026).

This post is rather long—far longer than the implementations!—so here is a brief overview of the sections for easier navigation and understanding where we’re headed.

- “Fixed-Point and Floating-Point Numbers” briefly reviews fixed-point and floating-point numbers, establishing some terminology and concepts needed for the rest of the post.

- “Unrounded Numbers” introduces the idea of unrounded numbers, inspired by the IEEE754 floating-point extended format.

- “Unrounded Scaling” defines the unrounded scaling primitive.

- “Fixed-Width Printing” formats floating-point numbers with a given (fixed) number of decimal digits, at most 18.

- “Parsing Decimals” parses decimal numbers of at most 19 digits into floating-point numbers.

- “Shortest-Width Printing” formats floating-point numbers using the shortest representation that parses back to the original number.

- “Fast Unrounded Scaling” reveals the short but subtle implementation of fast unrounded scaling that enables those simple algorithms.

- “Sketch of a Proof of Fast Scaling” briefly sketches the proof that the fast unrounded scaling algorithm is correct. A companion post, “Fast Unrounded Scaling: Proof by Ivy” provides the full details.

- “Omit Needless Multiplications” uses a key idea from the proof to optimize the fast unrounded scaling implementation further, reducing it to a single 64-bit multiplication in many cases.

- “Performance” compares the performance of the implementation of these algorithms against earlier ones.

- “History and Related Work” examines the history of solutions to the floating-point printing and parsing problems and traces the origins of the specific ideas used in this post’s algorithms.

For the last decade, there has been a new algorithm for floating-point printing and parsing every few years. Given the simplicity and speed of the algorithms in this post and the increasingly small deltas between successive algorithms, perhaps we are nearing an optimal solution.

Fixed-Point and Floating-Point Numbers

Fixed-point numbers have the form for an integer mantissa , constant base , and constant (fixed) exponent . We can create fixed-point representations in any base, but the most common are base 2 (for computers) and base 10 (for people). This diagram shows fixed-point numbers at various scales that can represent numbers between 0 and 1:

Using a smaller scaling factor increases precision at the cost of larger mantissas. When representing very large numbers, we can use larger scaling factors to reduce the mantissa size. For example, here are various representations of numbers around one billion:

Floating-point numbers are the same as base-2 fixed-point numbers except that changes with the overall size of the number. Small numbers use very small scaling factors while large numbers use large scaling factors, aiming to keep the mantissas a constant length. For float64s, the exponent is chosen so that the mantissa has 53 bits, meaning . For example, for numbers in , float64s use ; for numbers in they use ; and so on.

[The notation is a half-open interval, which includes but not . In contrast, the closed interval includes both and . We write or to say that is in that interval. Using this notation, means .]

In addition to limiting the mantissa size, we must also limit the exponent, to keep the overall number a fixed size. For float64s, assuming , the exponent .

A float64 consists of 1 sign bit, 11 exponent bits, and 52 mantissa bits.

The normal 11-bit exponent encodings 0x001 through 0x3fe denote through .

For those, the mantissa ,

and it is encoded into only 52 bits by omitting the leading 1 bit.

The special exponent encoding 0x3ff is used for infinity and not-a-number.

That leaves the encoding 0x000, which is also special.

It denotes (like 0x001 does)

but with mantissas without an implicit leading 1.

These subnormals or denormalized numbers [8]

continue the fixed-point scale down to zero,

which ends up encoded (not coincidentally) as 64 zero bits.

Other definitions of floating point numbers use different interpretations. For example the IEEE754 standard uses with , while the C standard libary frexp function uses with . Both of these choices make itself a fixed-point number instead of an integer. Our integer definition lets us use integer math. These interpretations are all equivalent and differ only by a constant added to .

This description of float64s applies to float32s as well, but with different constants. This table summarizes the two encodings:

| float32 | float64 | |

|---|---|---|

| sign bits | 1 | 1 |

| encoded mantissa bits | 23 | 52 |

| encoded exponent bits | 8 | 11 |

| exponent range for | ||

| exponent range for integer | ||

| normal numbers | ||

| subnormal numbers | ||

| exponent range for 64-bit | ||

| normal numbers | ||

| subnormal numbers |

To convert a float64 to its bits, we use Go’s math.Float64bits.

func unpack64(f float64) (uint64, int) {

const shift = 64 - 53

const minExp = -(1074 + shift)

b := math.Float64bits(f)

m := 1<<63 | (b&(1<<52-1))<<shift

e := int((b >> 52) & (1<<shift - 1))

if e == 0 {

m &^= 1 << 63

e = minExp

s := 64 - bits.Len64(m)

return m << s, e - s

}

return m, (e - 1) + minExp

}

To convert back, we use Go’s math.Float64frombits.

func pack64(m uint64, e int) float64 {

if m&(1<<52) == 0 {

return math.Float64frombits(m)

}

return math.Float64frombits(m&^(1<<52) | uint64(1075+e)<<52)

}[Other presentations use “fraction” and “significand” instead of “mantissa”. This post uses mantissa for consistency with my 2011 post and because I generally agree with Agatha Mallett’s excellent “In Defense of ‘Mantissa’”.]

Unrounded Numbers

Floating-point operations are defined as if computed exactly to infinite precision and then rounded to the nearest actual floating-point number, breaking ties by rounding to an even mantissa. Of course, real implementations don’t use infinite precision; they only keep enough precision to round properly. We will use the same idea. In our algorithms, we want the scaling operation to eventually evaluate to an integer, but we want to give the caller control over the rounding step. So instead of returning an integer, we will return an unrounded number, which contains all the information needed to round it in a variety of ways.

The unrounded form of any real number , which we will write as as , is the truncated integer part of followed by two more bits. Those bits indicate (1) whether the fractional part of was at least ½, and (2) whether the fractional part was not exactly 0 or ½. If you think of as a real number written in binary, the first extra bit is the bit immediately after the “binary point”—the bit that represents , aka the ½ bit—and the second extra bit is the OR of all the bits after the ½ bit.

This definition applies even to numbers that require an infinite binary representation. For example, just as 1/3 requires an infinite decimal representation ‘’, 1.6 requires an infinite binary representation ‘’. The unrounded version is finite: ‘’. But instead of reading unrounded numbers in binary, let’s print as where is the integer part , is 0 or 5, and is ‘+’ when the second bit is 1. Then is written ‘’.

Let’s implement unrounded numbers in Go.

type unrounded uint64

func unround(x float64) unrounded {

return unrounded(math.Floor(4*x)) | bool2[unrounded](math.Floor(4*x) != 4*x)

}

func (u unrounded) String() string {

return fmt.Sprintf("⟨%d.%d%s⟩", u>>2, 5*((u>>1)&1), "+"[1-u&1:])

}

The bool2 function converts a boolean to an integer.

(The Go compiler will implement this using an inlined conditional move.)

func bool2[T ~int | ~uint64](b bool) T {

if b {

return 1

}

return 0

}

We won’t use the unround constructor in our actual code, but it’s helpful for playing.

For example, we can try the examples we just saw:

row("x", "raw", "str")

for _, x := range []float64{6, 6.001, 6.499, 6.5, 6.501, 6.999, 7} {

u := unround(x)

row(x, uint64(u), u)

}

table()

x raw str 6 24 ⟨6.0⟩ 6.001 25 ⟨6.0+⟩ 6.499 25 ⟨6.0+⟩ 6.5 26 ⟨6.5⟩ 6.501 27 ⟨6.5+⟩ 6.999 27 ⟨6.5+⟩ 7 28 ⟨7.0⟩

The unrounded form holds the information needed by all the usual rounding operations. Adding 0, 1, 2, or 3 and then dividing by four (or shifting right by two) yields: floor, round with ½ rounding down, round with ½ rounding up, and ceiling. In floating-point math, we want to round with ½ rounding to even, meaning 1½ and 2½ both round to 2. We can do that by adding , where is 0 or 1 according to whether is odd. That’s just the low bit of : .

Putting that all together:

In Go:

func (u unrounded) floor() uint64 { return uint64((u + 0) >> 2) }

func (u unrounded) roundHalfDown() uint64 { return uint64((u + 1) >> 2) }

func (u unrounded) round() uint64 { return uint64((u + 1 + (u>>2)&1) >> 2) }

func (u unrounded) roundHalfUp() uint64 { return uint64((u + 2) >> 2) }

func (u unrounded) ceil() uint64 { return uint64((u + 3) >> 2) }row("x", "floor", "round½↓", "round", "round½↑", "ceil")

for _, x := range []float64{6, 6.25, 6.5, 6.75, 7, 7.5, 8.5} {

u := unround(x)

row(u, u.floor(), u.roundHalfDown(), u.round(), u.roundHalfUp(), u.ceil())

}

table()

x floor round½↓ round round½↑ ceil ⟨6.0⟩ 6 6 6 6 6 ⟨6.0+⟩ 6 6 6 6 7 ⟨6.5⟩ 6 6 6 7 7 ⟨6.5+⟩ 6 7 7 7 7 ⟨7.0⟩ 7 7 7 7 7 ⟨7.5⟩ 7 7 8 8 8 ⟨8.5⟩ 8 8 8 9 9

Dividing unrounded numbers preserves correct rounding as long as the second extra bit is maintained correctly: once it is set to 1, it has to stay a 1 in all future results. This gives the second extra bit its shorter name: the sticky bit.

To divide an unrounded number, we do a normal divide but force the sticky bit to 1 when there is a remainder. Right shift does the same.

For example, if we rounded 15.4 to an integer 15 and then divided it by 6, we’d get 2.5, which rounds down to 2, but the more precise answer would be 15.4/6 = 2.57, which rounds up to 3. An unrounded division handles this correctly:

Let’s implement division and right shift in Go:

func (u unrounded) div(d uint64) unrounded {

x := uint64(u)

return unrounded(x/d) | u&1 | bool2[unrounded](x%d != 0)

}

func (u unrounded) rsh(s int) unrounded {

return u>>s | u&1 | bool2[unrounded](u&((1<<s)-1) != 0)

}u := unround(15.1).div(6) fmt.Println(u, u.round())

⟨2.5+⟩ 3

Finally, we are going to need to be able to nudge an unrounded number up or down before computing a ceiling or floor, as if we added or subtracting a tiny amount. Let’s add that:

func (u unrounded) nudge(δ int) unrounded { return u + unrounded(δ) }row("x", "nudge(-1).floor", "floor", "ceil", "nudge(+1).ceil")

for _, x := range []float64{15, 15.1, 15.9, 16} {

u := unround(x)

row(u, u.nudge(-1).floor(), u.floor(), u.ceil(), u.nudge(+1).ceil())

}

x nudge(-1).floor floor ceil nudge(+1).ceil ⟨15.0⟩ 14 15 15 16 ⟨15.0+⟩ 15 15 16 16 ⟨15.5+⟩ 15 15 16 16 ⟨16.0⟩ 15 16 16 17

Floating-point hardware maintains three extra bits to round all arithmetic operations correctly. For just division and right shift, we can get by with only two bits.

Unrounded Scaling

The fundamental insight of this post is that all floating-point conversions can be written correctly and simply using unrounded scaling, which multiplies a number by a power of two and a power of ten and returns the unrounded product.

When is negative, the value cannot be stored exactly in any finite binary floating-point number, so any implementation of uscale must be careful.

In Go, we can implement uscale using big integers and an unrounded division:

func uscale(x uint64, e, p int) unrounded {

num := mul(big(4), big(x), pow(2, max(0, p)), pow(10, max(0, e)))

denom := mul( pow(2, max(0, -p)), pow(10, max(0, -e)))

div, mod := divmod(num, denom)

return unrounded(div.uint64() | bool2[uint64](!mod.isZero()))

}

The max expressions choose between multiplying into num when

or multiplying into denom when ,

and similarly for .

The divmod implements the floor, and mod.isZero reports

whether the floor was exact.

This implementation of uscale is correct but inefficient. In our usage, and will mostly cancel out, typically with opposite signs, and the input and result , will always fit in 64 bits. That limited input domain and range makes it possible to implement a very fast, completely accurate uscale, and we’ll see that implementation later.

Our actual implementation will be split into two functions,

to allow sharing some computations derived from and .

Instead of uscale(x, e, p), the fast Go version will be called as uscale(x, prescale(e, p, log2Pow10(p))).

Also, callers are responsible for passing in an left-shifted to have its

high bit set.

The unpack function we looked at already arranged that for its result,

but otherwise callers need to do something like:

shift = 64 - bits.Len64(x) ... uscale(x<<shift, prescale(e-shift, p, log2Pow10(p))) ...

Conceptually, uscale maps numbers on one fixed-point scale to numbers on another, including converting between binary and decimal scales. For example, consider the scales and :

Given from the side, maps to the equivalent point on the side; and given from the , maps to the equivalent point on the side. Before we look at the fast implementation of , let’s look at how it simplifies all the floating-point printing and parsing algorithms.

Fixed-Width Printing

Our first application of uscale is fixed-width printing. Given , we want to compute its approximate equivalent , where has exactly digits. It only takes 17 digits to uniquely identify any float64, so we’re willing to limit , which will ensure fits in a uint64. The strategy is to multiply by for some and then round it to an integer . Then the result is .

The -digit requirement means . From this we can derive :

It is okay for to be too big—we will get an extra digit that we can divide away—so we can approximate as , where is the bit length of . That gives us . With this derivation of , uscale does the rest of the work.

The floor expression is a simple linear function and can be computed exactly for our inputs using fixed-point arithmetic:

func log10Pow2(x int) int {

return (x * 78913) >> 18

}

The log2Pow10 function, which we mentioned above and need to

use when calling prescale, is similar:

func log2Pow10(x int) int {

return (x * 108853) >> 15

}Now we can put everything together:

func FixedWidth(f float64, n int) (d uint64, p int) {

if n > 18 {

panic("too many digits")

}

m, e := unpack64(f)

p = n - 1 - log10Pow2(e+63)

u := uscale(m, prescale(e, p, log2Pow10(p)))

d = u.round()

if d >= uint64pow10[n] {

d, p = u.div(10).round(), p-1

}

return d, -p

}That’s the entire conversion!

The code splits into , ;

computes as just described;

and then uses uscale and round to compute

.

If the result has an extra digit,

either because our approximate log made too big,

or because of rollover during rounding,

we divide the unrounded form by 10, round again, and update .

When we approximated by counting bits,

we used the exact log of the greatest power of two less than or equal to ,

so the computed must be less than twice the intended limit ,

meaning the leading digit (if there are too many digits) must be 1.

And rollover only happens for ‘’,

so it is not possible to have both an extra digit and rollover.

As an example conversion, consider a float64 approximation of () to 15 decimal digits. We have , , and , so .

The and scales align like this:

Then returns the unrounded number ‘314159265358979.0+’, which rounds to 314159265358979. Our answer is then .

Parsing Decimals

Unrounded scaling also lets us parse decimal representations of floating-point numbers efficiently. Let’s assume we’ve taken care of parsing a string like ‘1.23e45’ and now have an integer and exponent like , . To convert to a float64, we can choose an appropriate so that and then return .

The derivation of is similar to the derivation of for printing:

Once again, it is okay to overestimate , so we can approximate , yielding . If is very large, will be very small, meaning we will be creating a subnormal, so we need to round to a smaller number of bits. To handle this, we cap at 1074, which caps at . As before, due to the approximation of , the scaled result is at most twice as large as our target, meaning it might have one extra bit to shift away.

func Parse(d uint64, p int) float64 {

if d > 1e19 {

panic("too many digits")

}

b := bits.Len64(d)

e := min(1074, 53-b-log2Pow10(p))

u := uscale(d<<(64-b), prescale(e-(64-b), p, log2Pow10(p)))

m := u.round()

if m >= 1<<53 {

m, e = u.rsh(1).round(), e-1

}

return pack64(m, -e)

}

FixedWidth and Parse demonstrate

exactly how similar printing and parsing really are.

In printing, we are given , and

find ; then converts binary to decimal.

In parsing, we are given , and find ;

then converts decimal to binary.

We can make parsing a little faster with a few hand optimizations.

This optimized version introduces lp to avoid calling log2Pow10 twice,

and it implements the extra digit handling in branch-free code.

func Parse(d uint64, p int) float64 {

if d > 1e19 {

panic("too many digits")

}

b := bits.Len64(d)

lp := log2Pow10(p)

e := min(1074, 53-b-lp)

u := uscale(d<<(64-b), prescale(e-(64-b), p, lp))

s := bool2[int](u >= unmin(1<<53))

u = (u >> s) | u&1

e = e - s

return pack64(u.round(), -e)

}

func unmin(x uint64) unrounded {

return unrounded(x<<2 - 2)

}Now we are ready for our next challenge: shortest-width printing.

Shortest-Width Printing

Shortest-width printing means to prepare a decimal representation

that a floating-point parser would convert back to the exact same float64,

using as few digits as possible.

When there are multiple possible shortest decimal outputs,

we insist on the one that is nearest the original input,

namely the correctly-rounded one.

In general, 17 digits are always enough to uniquely identify a float64,

but sometimes fewer can be used, even down to a single digit in numbers like 1, 2e10, and 3e−42.

An obvious approach would be to use FixedPrint for increasing values of n,

stopping when Parse(FixedPrint(f, n)) == f.

Or maybe we should derive an equation for n and then use FixedPrint(f, n) directly.

Surprisingly, neither approach works:

Short(f) is not necessarily FixedPrint(f, n) for some n.

The simplest demonstration of this is ,

which looks like this:

Because is a power of two, the floating-point exponent changes at , as does the spacing between floating-point numbers. The next smallest value is , marked on the diagram as . The dotted lines mark the halfway points between and its nearest floating point neighbors. The accurate decimal answers are those at or between the dotted lines, all of which convert back to .

The correct rounding of to 16 digits ends in …901: the next digit in is 3,

so we should round down.

However, because of the spacing change around ,

that correct decimal rounding does not convert back to .

A FixedPrint loop would choose a 17-digit form instead.

But there is an accurate 16-digit form, namely …902.

That decimal is closer to than it is to any other float64,

making it an accurate .

And since the closer 16-digit value …901 is not an accurate ,

Short should use …902 instead.

Assuming as usual that , let’s define to be the distance between the midpoints from to its floating-point neighbors. Normally those neighbors are in either direction—the midpoints are —so . At a power of two with an exponent change, the lower midpoint is instead , so . The rounding paradox can only happen for powers of two with this kind of skewed footprint.

All that is to say we cannot use FixedWidth with “the right ”.

But we can use scale directly with “the right .”

Specifically, we can compute the midpoints between

and its floating-point neighbors

and scale them to obtain the

minimum and maximum valid choices for .

Then we can make the best choice:

-

If one of the valid ends in 0, use it after removing trailing zeros.

(Choosing the right will allow at most ten consecutive integers, so at most will one end in 0.) - If there is only one valid , use it.

- Otherwise there are at least two valid , at least one on each side of ; use the correctly rounded one.

Here is an example of the first case: one of the valid ends in zero.

We already saw an example of the second case: only one valid . For numbers with symmetric footprints, that will be the correctly rounded . As we saw for numbers with skewed footprints, that may not be the correctly rounded , but it is still the correct answer.

Finally, here is an example of the third case: multiple valid , but none that end in zero. Now we should use the correctly rounded one.

This sounds great, but how do we determine the right ? We want to allow at least one decimal integer, but at most ten, meaning . Luckily, we can hit that target exactly.

For a symmetric footprint:

For a skewed footprint:

For the symmetric footprint, we can use log10Pow2,

but for the skewed footprint, we need a new approximation:

func skewed(e int) int {

return (e*631305 - 261663) >> 21

}We should worry about a footprint with decimal width exactly 1, since if had an odd mantissa, the midpoints would be excluded. In that case, if the decimals were the exact midpoints, there would be no decimal between them, making the conversion invalid. But it turns out we should not worry too much. For a skewed footprint, can never be exactly 1, because nothing can divide away the 3. For a symmetric footprint, can only happen for , but then scaling is a no-op, so that the decimal integers are exactly the binary integers. The non-integer midpoints map to non-integer decimals.

When we compute the decimal equivalents of the midpoints, we will use ceiling and floor instead of rounding them, to make sure the integer results are valid decimal answers. If the mantissa is odd, we will nudge the unrounded forms inward slightly before taking the ceiling or floor, since rounding will be away from .

The Go code is:

func Short(f float64) (d uint64, p int) {

const minExp = -1085

m, e := unpack64(f)

var min uint64

z := 11

if m == 1<<63 && e > minExp {

p = -skewed(e + z)

min = m - 1<<(z-2)

} else {

if e < minExp {

z = 11 + (minExp - e)

}

p = -log10Pow2(e + z)

min = m - 1<<(z-1)

}

max := m + 1<<(z-1)

odd := int(m>>z) & 1

pre := prescale(e, p, log2Pow10(p))

dmin := uscale(min, pre).nudge(+odd).ceil()

dmax := uscale(max, pre).nudge(-odd).floor()

if d = dmax / 10; d*10 >= dmin {

return trimZeros(d, -(p - 1))

}

if d = dmin; d < dmax {

d = uscale(m, pre).round()

}

return d, -p

}

Notice that this algorithm requires either two or three calls to uscale.

When the number being printed has only one valid representation

of the shortest length, we avoid the third call to uscale.

Also notice that the prescale result is shared by all three calls.

When , ,

meaning it won’t be left shifted as far as possible

during the call to uscale.

Although we could detect this case and call uscale

with and ,

using unmodified is fine:

it is still shifted enough that the bits uscale

needs to return will stay in the high 64 bits of the 192-bit product,

and using the same

lets us use the same prescale work for all three calls.

Trimming Zeros

The trimZeros function used in Short removes any trailing zeros from its argument,

updating the decimal power. An unoptimized version is:

func trimZeros(x uint64, p int) (uint64, int) {

if x%10 != 0 {

return x, p

}

x /= 10

p += 1

if x%100000000 == 0 {

x /= 100000000

p += 8

}

if x%10000 == 0 {

x /= 10000

p += 4

}

if x%100 == 0 {

x /= 100

p += 2

}

if x%10 == 0 {

x /= 10

p += 1

}

return x, p

}The initial removal of a single zero gives an early return for the common case of having no zeros. Otherwise, the code makes four additional checks that collectively remove up to 16 more zeros. For outputs with many zeros, these four checks run faster than a loop removing one zero at a time.

When compiling this code,

the Go compiler reduces the remainder checks to multiplications

using the following well-known optimization.

An exact uint64 division where

can be implemented by where

is the uint64 multiplicative inverse of , meaning :

Since is also the multiplicative inverse of , is

lossless—all the exact multiples of map to all of —so

the non-multiples are forced to map to larger values.

This observation gives a quick test for whether is an exact multiple of :

check whether .

Only odd have multiplicative inverses modulo powers of two, so even divisors require more work. To compute an exact division , we can use instead. To check for remainder, we need to check that those low bits are all zero before we shift them away. We can merge that check with the range check by rotating those bits into the high part instead of discarding them: check whether , where is right rotate.

The Go compiler does this transformation automatically

for the if conditions in trimZeros,

but inside the if bodies, it does not reuse the

exact quotient it just computed.

I considered changing the compiler to recognize that pattern,

but instead I wrote out the remainder check by hand

in the optimized version, allowing me to reuse the computed exact quotients:

func trimZeros(x uint64, p int) (uint64, int) {

const (

maxUint64 = ^uint64(0)

inv5p8 = 0xc767074b22e90e21

inv5p4 = 0xd288ce703afb7e91

inv5p2 = 0x8f5c28f5c28f5c29

inv5 = 0xcccccccccccccccd

)

if d := bits.RotateLeft64(x*inv5, -1); d <= maxUint64/10 {

x = d

p += 1

} else {

return x, p

}

if d := bits.RotateLeft64(x*inv5p8, -8); d <= maxUint64/100000000 {

x = d

p += 8

}

if d := bits.RotateLeft64(x*inv5p4, -4); d <= maxUint64/10000 {

x = d

p += 4

}

if d := bits.RotateLeft64(x*inv5p2, -2); d <= maxUint64/100 {

x = d

p += 2

}

if d := bits.RotateLeft64(x*inv5, -1); d <= maxUint64/10 {

x = d

p += 1

}

return x, p

}This approach to trimming zeros is from Dragonbox. For more about the general optimization, see Warren’s Hacker’s Delight [34], sections 10-16 and 10-17.

Fast, Accurate Scaling

The conversion algorithms we examined are nice and simple.

For them to be fast, uscale needs to be fast while remaining correct.

Although multiplication by can be implemented by shifts,

uscale cannot actually compute or multiply by

—that would take too long when is a large positive or negative number.

Instead, we can approximate as a floating-point number with a 128-bit mantissa,

looked up in a table indexed by .

Specifically, we will use and ,

ensuring that .

We will write a separate program to generate this table.

It emits Go code defining pow10Min, pow10Max, and pow10Tab:

pow10Tab[0] holds the entry for .

To figure out how big the table needs to be,

we can analyze the three functions we just wrote.

-

FixedWidthconverts floating-point to decimal. It needs to calluscalewith a 53-bit , , and . -

Shortalso converts floating-point to decimal. It needs to calluscalewith a 55-bit , , and . -

Parseconverts decimal to floating-point. It needs to calluscalewith a 64-bit and . (Outside that range of ,Parsecan return 0 or infinity.)

So the table needs to provide answers for .

If , then .

In all of our algorithms, the result of uscale was always small—at most 64 bits.

Since is 128 bits and is even bigger, must be negative,

so this computation is

(x*pm) >> -(e+pe).

Because of the ceiling, may be too large by an error ,

so may be too large by an error .

To round exactly, we care whether any of the shifted bits is 1,

but may change the low bits,

so we can’t trust them.

Instead, we will throw them away.

and use only the upper bits to compute our unrounded number.

That is the entire idea!

Now let’s look at the implementation.

The prescale function returns a scaler with and a shift count :

type scaler struct {

pm pmHiLo

s int

}

type pmHiLo struct {

hi uint64

lo uint64

}We want the shift count to reserve two extra bits for the unrounded representation and to apply to the top 64-bit word of the 192-bit product, which gives this formula:

That translates directly to Go:

func prescale(e, p, lp int) scaler {

return scaler{pm: pow10Tab[p-pow10Min], s: -(e + lp + 3)}

}

In uscale, since the caller left-justified to 64 bits,

discarding the low bits means discarding the

lowest 64 bits of the product, which we skip computing entirely.

Then we use the middle 64-bit word and the low bits

of the upper word to set the sticky bit in the result.

func uscale(x uint64, c scaler) unrounded {

hi, mid := bits.Mul64(x, c.pm.hi)

mid2, _ := bits.Mul64(x, c.pm.lo)

mid, carry := bits.Add64(mid, mid2, 0)

hi += carry

sticky := bool2[unrounded](mid != 0 || hi&((1<<c.s)-1) != 0)

return unrounded(hi>>c.s) | sticky

}It is mind-boggling that this works, but it does. Of course, you shouldn’t take my word for it. We have to prove it correct.

Sketch of a Proof of Fast Scaling

To prove that our fast uscale algorithm is correct,

there are three cases: small positive ,

small negative ,

and large .

The actual proof, especially for large ,

is non-trivial,

and the details are quite a detour from

our fast scaling implementations,

so this section only sketches the basic ideas.

For the details, see the accompanying post, “Fast Unrounded Scaling: Proof by Ivy.”

Remember from the previous section that for some . Since , ’s 128 bits need only represent the part; the can always be handled by .

For , fits in the top 64 bits of the 128-bit .

Since is exact,

the only possible error is introduced by discarding the bottom bits.

Since the bottom 64 bits of are zero,

the bits we discard are all zero.

So uscale is correct for small positive .

For ,

is approximating division by (remember that is a positive number!).

The 128-bit approximation is precise enough that when is a

multiple of , only the lowest bits are non-zero;

discarding them keeps the unrounded form exact.

And when is not a multiple of ,

the result has a fractional part that must be at least

away from an integer.

That fractional separation is much larger than the maximum error in the product,

so the high bits saved in the unrounded form are correct;

the fraction is also repeating, so that there is guaranteed

to be a 1 bit to cause the unrounded form to be marked inexact.

So uscale is correct for small negative .

Finally, we must handle large , which always have a non-zero error

and therefore should always return unrounded numbers marked inexact

(with the sticky bit set to 1).

Consider the effect of adding a small error to the idealized “correct” ,

producing .

The error is at most 64 bits.

Adding that error to the 192-bit product can certainly affect

the low 64 bits, and it may also generate a carry out of the low 64

into the middle 64 bits.

The carry turns 1 bits into 0 bits from right to left

until it hits a 0 bit;

that first 0 bit becomes a 1, and the carry stops.

The key insight is that seeing a 1 in the middle bits

is proof that the carry did not reach the high bits,

so the high bits are correct.

(Seeing a 1 in the middle bits also ensures that

the unrounded form is marked inexact, as it must be,

even though we discarded the low bits.)

Using a program backed by careful math, we can analyze all the in our table,

showing that every possible has a 1 in the middle bits.

So uscale is correct for large .

Omit Needless Multiplications

We have a fast and correct uscale, but we can make it faster

now that we understand the importance of carry bits.

The idea is to compute the high 64 bits of the product

and then use it directly whenever possible, avoiding the computation

of the remaining 64 bits at all.

To make this work, we need the high 64 bits to be rounded up,

a ceiling instead of a floor.

So we will change the pmHiLo from representing

to .

type pmHiLo struct {

hi uint64

lo uint64

}The exact computation using this form would be:

hi, mid := bits.Mul64(x, c.pm.hi) mid2, lo := bits.Mul64(x, c.pm.lo) mid, carry := bits.Sub64(mid, mid2, bool2[uint64](lo > 0)) hi -= carry return unrounded(hi >> c.s) | bool2[unrounded](hi&((1<<c.s)-1) != 0 || mid != 0)

The 128-bit product computed on the first line may be too big by an error of up to , which may or may not affect the high 64 bits; The middle three lines correct the product, possibly subtracting 1 from . Like in the proof sketch, if any of the bottom bits of the approximate is a 1 bit, that 1 bit would stop the subtracted carry from affecting the higher bits, indicating that we don’t need to correct the product.

Using this insight, the optimized uscale is:

func uscale(x uint64, c scaler) unrounded {

hi, mid := bits.Mul64(x, c.pm.hi)

sticky := uint64(1)

if hi&(1<<(c.s&63)-1) == 0 {

mid2, _ := bits.Mul64(x, c.pm.lo)

sticky = bool2[uint64](mid-mid2 > 1)

hi -= bool2[uint64](mid < mid2)

}

return unrounded(hi>>c.s | sticky)

}The fix-up looks different from the exact computation above but it has the same effect. We don’t need the actual final value of , only the carry and its effect on the sticky bit.

On some systems, notably x86-64, bits.Mul64 computes both results in a single instruction.

On other systems, notably ARM64, bits.Mul64 must use two different instructions;

it helps on those systems to write the code this way,

optimizing away the computation for the low half of .

The more bits that are being shifted out of hi,

the more likely it is that a 1 bit is being shifted out,

so that we have an answer after only the first bits.Mul64.

When Short calls uscale, it passes two that

differ only in a single bit

and multiplies them by the same .

While one of them might clear the low bits of ,

the other is unlikely to also clear them,

so we are likely to hit the fast path at least once,

if not twice.

In the case where Short calls uscale three times,

we are likely to hit the fast path at least twice.

This optimization means that, most of the time, a uscale

is implemented by a single wide multiply.

This is the main reason that Short runs faster than

Ryū, Schubfach, and Dragonbox, as we will see in the next section.

Performance

I promised these algorithms would be simple and fast. I hope you are convinced about simple. (If not, keep in mind that the implementations in widespread use today are far more complicated!) Now it is time to evaluate ‘fast’ by comparing against other implementations. All the other implementations are written in C or C++ and compiled by a C/C++ compiler. To isolate compilation differences, I translated the Go code to C and measured both the Go code and the C translation.

I ran the benchmarks on two systems.

- Apple M4 (2025 MacBook Air ‘Mac16,12’), 32 GB RAM, macOS 26.1, Apple clang 17.0.0 (clang-1700.6.3.2)

- AMD Ryzen 9 7950X, 128 GB RAM, Linux 6.17.9 and libc6 2.39-0ubuntu8.6, Ubuntu clang 18.1.3 (1ubuntu1)

Both systems used Go 1.26rc1.

The full benchmark code is in the rsc.io/fpfmt package.

Printing Text

Real implementations generate strings, so we need to write code to convert the integers we have been returning into digit sequences, like this:

func formatBase10(a []byte, u uint64) {

for nd := len(a) - 1; nd >= 0; nd-- {

a[nd] = byte(u%10 + '0')

u /= 10

}

}

Unfortunately, if we connect our fast FixedWidth and Short to this

version of formatBase10, benchmarks spend most of their time in the formatting loop.

There are a variety of clever ways to speed up digit formatting.

For our purposes, it suffices to use the old trick of

splitting the number into two-digit chunks and

then converting each chunk by

indexing a 200-byte lookup table (more precisely, a “lookup string”) of all 2-digit values from 00 to 99:

const i2a = "00010203040506070809" + "10111213141516171819" + "20212223242526272829" + "30313233343536373839" + "40414243444546474849" + "50515253545556575859" + "60616263646566676869" + "70717273747576777879" + "80818283848586878889" + "90919293949596979899"

Using this table and unrolling the loop to allow the

compiler to optimize away bounds checks, we end up with formatBase10:

func formatBase10(a []byte, u uint64) {

nd := len(a)

for nd >= 8 {

x3210 := uint32(u % 1e8)

u /= 1e8

x32, x10 := x3210/1e4, x3210%1e4

x1, x0 := (x10/100)*2, (x10%100)*2

x3, x2 := (x32/100)*2, (x32%100)*2

a[nd-1], a[nd-2] = i2a[x0+1], i2a[x0]

a[nd-3], a[nd-4] = i2a[x1+1], i2a[x1]

a[nd-5], a[nd-6] = i2a[x2+1], i2a[x2]

a[nd-7], a[nd-8] = i2a[x3+1], i2a[x3]

nd -= 8

}

x := uint32(u)

if nd >= 4 {

x10 := x % 1e4

x /= 1e4

x1, x0 := (x10/100)*2, (x10%100)*2

a[nd-1], a[nd-2] = i2a[x0+1], i2a[x0]

a[nd-3], a[nd-4] = i2a[x1+1], i2a[x1]

nd -= 4

}

if nd >= 2 {

x0 := (x % 1e2) * 2

x /= 1e2

a[nd-1], a[nd-2] = i2a[x0+1], i2a[x0]

nd -= 2

}

if nd > 0 {

a[0] = byte('0' + x)

}

}This is more code than I’d prefer, but it is at least straightforward. I’ve seen much more complex versions.

With formatBase10, we can build Fmt, which formats in standard exponential notation:

func Fmt(s []byte, d uint64, p, nd int) int {

formatBase10(s[1:nd+1], d)

p += nd - 1

s[0] = s[1]

n := nd

if n > 1 {

s[1] = '.'

n++

}

s[n] = 'e'

if p < 0 {

s[n+1] = '-'

p = -p

} else {

s[n+1] = '+'

}

if p < 100 {

s[n+2] = i2a[p*2]

s[n+3] = i2a[p*2+1]

return n + 4

}

s[n+2] = byte('0' + p/100)

s[n+3] = i2a[(p%100)*2]

s[n+4] = i2a[(p%100)*2+1]

return n + 5

}

When calling Fmt with a FixedWidth result, we know the digit count nd already.

For a Short result, we can compute the digit count easily from the bit length:

func Digits(d uint64) int {

nd := log10Pow2(bits.Len64(d))

return nd + bool2[int](d >= uint64pow10[nd])

}Fixed-Width Performance

To evaluate fixed-width printing,

we need to decide which floating-point values to convert.

I generated 10,000 uint64s in the range and used them as

float64 bit patterns.

The limited range avoids negative numbers, infinities, and NaNs.

The benchmarks all use Go’s

ChaCha8-based generator

with a fixed seed for reproducibility.

To reduce timing overhead, the benchmark builds an array of 1000 copies of the value

and calls a function that converts every value in the array in sequence.

To reduce noise, the benchmark times that function call 25 times and uses the median timing.

We also have to decide how many digits to ask for:

longer sequences are more difficult.

Although I investigated a wider range, in this post I’ll show

two representative widths: 6 digits (C printf’s default) and 17 digits

(the minimum to guarantee accurate round trips, so widely used).

The implementations I timed are:

-

dblconv: Loitsch’s double-conversion library, using the

ToExponentialfunction. This library, used in Google Chrome, implements a handful of special cases for small binary exponents and falls back to a bignum-based printer for larger exponents. -

dmg1997: Gay’s

dtoa.c, archived in 1997. For our purposes, this represents Gay’s original C implementation described in his technical report from 1990 [11]. I confirmed that this 1997 snapshot runs at the same speed as (and has no significant code changes compared to) another copy dating back to May 1991 or earlier. -

dmg2017: Gay’s

dtoa.c, archived in 2017. In 2017, Gay published an updated version ofdtoa.cthat usesuint64math and a table of 96-bit powers of ten. It is significantly faster than the original version (see below). In November 2025, I confirmed that the latest version runs at the same speed as this one. -

libc:

The C standard library conversion using

sprintf("%.*e", prec-1). The conversion algorithm varies by C library. The macOS C library seems to wrap a pre-2017 version ofdtoa.c, while Linux’s glibc uses its own bignum-based code. In general the C library implementations have not kept pace with recent algorithms and are slower than any of the others. -

ryu: Adams’s Ryū library, using the

d2exp_bufferedfunction. It uses the Ryū Printf algorithm [3]. - uscale: The unrounded scaling approach, using the Go code in this post.

- uscalec: A C translation of the unrounded scaling Go code.

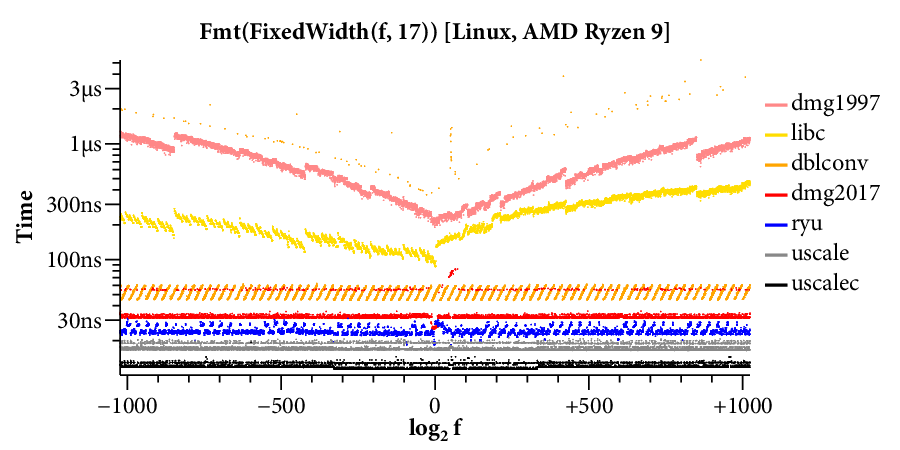

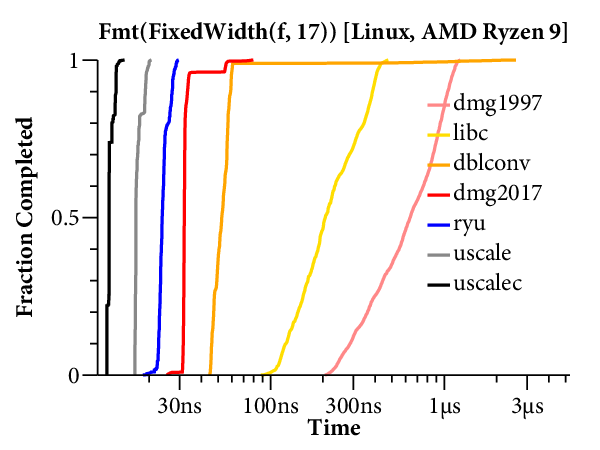

Here is a scatterplot showing the times required to format to 17 digits, running on the Linux system:

(Click on any of the graphs in this post for a larger view.)

The X axis is the log of the floating point input , and the Y axis is the time required for a single conversion of the given input. The scatterplot makes many things clear. For example, it is obvious that there are two kinds of implementations. Those that use bignums take longer for large exponents and have a “winged” scatterplot, while those that avoid bignums run at a mostly constant speed across the entire exponent range. The scatterplot also highlights many interesting data-dependent patterns in the timings, most of which I have not investigated. A friend remarked that you could probably spend a whole career analyzing the patterns in this one plot.

For our purposes, it would help to have a clearer comparison of the speed of the different algorithms. The right tool for that is a plot of the cumulative distribution function (CDF), which looks like this:

Now time is on the X axis (still log scale), and the Y axis plots what fraction of the inputs ran in that time or less. For example, we can see that dblconv’s fast path applies to most inputs, but its slow path is much slower than Linux glibc or even Gay’s original C library.

The CDF only plots the middle 99.9% of timings (dropping the 0.05% fastest and slowest), to avoid tails caused by measurement noise. In general, measurements are noisier on the Mac because ARM64 timers only provide ~20ns precision, compared to the x86’s sub-nanosecond precision.

Here are the scatterplots and CDFs for 6-digit output on the two systems:

For short output, various special-case optimizations are possible to avoid bignums, and the scatterplots make clear that all the implementations do that, except for Linux glibc. It surprises me that both libc implementations are so much slower than David Gay’s original dtoa from 1990 (dmg1997). I expected that any new attempt at floating-point printing would at least make sure it was as fast as the canonical reference implementation.

Here are the results for 17-digit output:

In this case, fewer optimizations are available, and libc has a winged scatterplot on both systems. The dblconv library has a fast path that can be taken about 99% of the time, but the scatterplot shows a shadow of a wing for the remaining 1%. The CDFs show the bignum-based implementations clearly: they are slower and have a more gradual slope. We can also read off the CDFs that dmg2017’s table-based fast path handles about 95% of the inputs.

In general, fast fixed-width printing has not seen much optimization attention. Unrounded scaling almost has the field to itself and is significantly faster than the other implementations.

Shortest-Width Performance

For shortest-width printing, I used the same set of random inputs as for fixed-width printing. The implementations are:

-

dblconv: Loitsch’s double-conversion library, using the

ToShortestfunction. It uses the Grisu3 algorithm [23]. -

dmg1997: Gay’s 1997

dtoa.cin shortest-output mode. -

dmg2017: Gay’s 2017

dtoa.cin shortest-output mode. -

dragonbox: Jeon’s dragonbox library, using the

jkj::dragonbox::to_charsfunction. It uses the Dragonbox algorithm [17]. -

ryu: Adams’s Ryū library, using the

d2s_bufferedfunction. It uses the Ryü algorithm [2]. - schubfach: A C++ translation of Giulietti’s Java implementation of Schubfach [12].

-

uscale: The unrounded scaling approach, using the Go code for

ShortandFmtin this post. - uscalec: A C translation of the unrounded scaling Go code.

All these implementations are running different code than for fixed-width printing. The C library does not provide shortest-width printing, so there is no libc implementation to compare against.

There is much more competition here. Other than Gay’s 1990 dtoa, everything runs quickly. From the CDFs, we can see that Gay’s 2017 dtoa fast path runs about 85% of the time. The C and Go unrounded scalings run at about the same speed as Ryū but a bit slower than Dragonbox. This turns out to be due mainly to Dragonbox’s digit formatter, not the actual floating-point conversion.

To remove digit formatting from the comparison, I ran a set of benchmarks

of just Short (which returns an integer, not a digit string)

and equivalent code from Dragonbox, Schubfach, and Ryū.

For Dragonbox, I used jkj::dragonbox::to_decimal.

For Schubfach and Ryū, I added new entry points that

return the integer and exponent instead of formatting them.

Schubfach delayed the trimming of zeros until after formatting,

so I added a call to the trimZeros used by Short,

which is in turn similar to the one used in Dragonbox.

The difference between these plots and the previous ones show that most of Dragonbox’s apparent speed before was in its digit formatter, not in the actual binary-to-decimal conversion. That converter effectively has different straight-line code path for each number length. It’s not surprising that it’s faster, but it’s more code than I’m willing to stomach myself.

The scatterplots show that the Ryū code’s special case for integer inputs helps for a few inputs (at the bottom of the plot) but runs slower than the general case for more inputs (at the top of the plot). On the other hand, the vertical lines of blue points near and are likely not algorithmic, nor is the vertical line of black points near . Both appear to be some kind of bad Apple M4 interaction when accessing a specific table entry. The specific inputs are executed in random order, so a clustering like this is not interference like a single overloaded moment on the machine. For a given built executable, the slow inputs are consistent; as the code and data sections move around when the program is changed, the slow inputs move too. There is also a general phenomenon that if you sample 10,000 points, some of them will run slower than others due to random hardware interactions. All this is to say that the tails of the CDFs for these very quick operations are not entirely trustworthy.

On a more reliable note, the CDFs show that Dragonbox has a fast path is taken about 60% of the time and runs faster than unrounded scaling, but the cost of that check is to make the remaining 40% slower than unrounded scaling. On average, they are about the same, but unrounded scaling is more consistent and less code.

Overall, unrounded scaling runs faster than or at the same speed as the others, especially when focusing on the core conversion. When formatting text, Dragonbox runs faster, but only because of its digit formatting code, not the code we are focusing on in this post.

Parsing Text

Like for printing, to compare against other parsing implementations

we need code to handle text, not just the integers passed to Parse.

Here is the parser I used.

It could be improved to handle arbitrary numbers of leading and trailing zeros,

negative numbers, and special values like zero, infinity and NaN,

but it is close enough for our purposes.

It is essentially a direct translation of the regular expression

[0-9]*(\.[0-9]*)?([Ee][+-]?[0-9]*),

with checks on the digit counts.

func ParseText(s []byte) (f float64, ok bool) {

isDigit := func(c byte) bool { return c-'0' <= 9 }

const maxDigits = 19

d := uint64(0)

frac := 0

i := 0

for ; i < len(s) && isDigit(s[i]); i++ {

d = d*10 + uint64(s[i]) - '0'

}

if i > maxDigits {

return

}

if i < len(s) && s[i] == '.' {

i++

for ; i < len(s) && isDigit(s[i]); i++ {

d = d*10 + uint64(s[i]) - '0'

frac++

}

if i == 1 || i > maxDigits+1 {

return

}

}

if i == 0 {

return

}

p := 0

if i < len(s) && (s[i] == 'e' || s[i] == 'E') {

i++

sign := +1

if i < len(s) {

if s[i] == '-' {

sign = -1

i++

} else if s[i] == '+' {

i++

}

}

if i >= len(s) || len(s)-i > 3 {

return

}

for ; i < len(s) && isDigit(s[i]); i++ {

p = p*10 + int(s[i]) - '0'

}

p *= sign

}

if i != len(s) {

return

}

return Parse(d, p-frac), true

}Parsing Performance

Now we can compare Parse to other implementations.

I generated 10,000 random inputs,

each of which was a random 19-digit sequence

with a decimal point after the first digit,

along with a random decimal exponent in the range [-300, 300].

(The full float64 decimal exponent range is [-308, 308],

but narrowing it avoids generating numbers

that underflow to 0 or overflow to infinity.)

The implementations are:

-

abseil: The Abseil library, using

absl::from_charsas of November 2025 (commit 48bf10f142). It uses the Eisel-Lemire algorithm [22]. -

libc: The C library’s

strtod. Linux glibc uses a bignum-based algorithm, while macOS 26 libc uses the Eisel-Lemire algorithm. -

dblconv: The double-conversion library’s

StringToDoublefunction. It uses Clinger’s algorithm [6] with simulated floating-point using 64-bit mantissas. -

dmg1997: Gay’s 1997 strtod, from

dtoa.cin 1997. It uses Clinger’s algorithm with hardware floating-point (float64s). -

dmg2017: Gay’s 2017 strtod, from

dtoa.cin 2017. It uses Clinger’s algorithm with simulated floating-point using 96-bit mantissas. -

fast_float: Lemire’s fast_float library, using the

fast_float::from_charsfunction. Unsurprisingly, it uses the Eisel-Lemire algorithm. -

uscale: The unrounded scaling approach, using the Go code for

ParseandUnfmtin this post. - uscalec: A C translation of the Go code in this post.

The surprise here is the macOS libc, which is competitive with unrounded scaling and fast_float. It turns out that macOS 26 shipped a new strtod based on the Eisel-Lemire algorithm.

Once again, to isolate the actual conversion from the text processing,

I also benchmarked Parse and equivalent code from fast_float.

I don’t understand the notch in the Go uscale on macOS, nor do I understand why the C uscale is faster than fast_float on macOS but only about the same speed on Linux. Since each conversion takes only a few nanoseconds, the answer may be subtle microarchitectural effects that I’m not particularly skilled at chasing down.

Overall, unrounded scaling is faster than—or in one case tied with—the other known algorithms for converting floating-point numbers to and from decimal representations.

The story is told of G. H. Hardy (and of other people) that during a lecture he said “It is obvious. . . Is it obvious?” left the room, and returned fifteen minutes later, saying “Yes, it’s obvious.” I was present once when Rogosinski asked Hardy whether the story were true. Hardy would admit only that he might have said “It’s obvious. . . Is it obvious?” (brief pause) “Yes, it’s obvious.”

— Ralph P. Boas, Jr., Lion Hunting and Other Mathematical Pursuits

If I have seen further, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.

— Isaac Newton

So I picked up my staff

And I followed the trail

Of his smoke to the mouth of the cave

And I bid him come out

Yea, forsooth, I did shout

“Ye fool dragon, be gone! Or behave!”

— Marsha Norman, The Secret Garden (musical)

People have been studying the problem of floating-point printing and parsing since the late 1940s. The solutions in this post, based on a fast, accurate unrounded scaling primitive, may seem obvious in retrospect, but they were certainly not obvious to me when I started down this trail. Nor were they obvious to the many people who studied this problem before, or we’d already be using these faster, simpler algorithms! As is often the case in computer science, the algorithms in this post connect individual ideas that have been known for decades. This section traces the history of the relevant ideas.

The companion post “Fast Unrounded Scaling: Proof by Ivy” has its own related work section that covers the history of proofs that a table of 128-bit powers of ten is sufficient for accurate results.

The earliest binary/decimal conversions in the literature are probably the ones in Goldstein and Von Neumann’s 1947 Planning and Coding Problems for an Electronic Computing Instrument [13]. They converted one digit at a time by repeated multiplication by 10 and modulo by 1, as did many conversions that followed.

The alternative to repeated multiplication by 10 is multiplication by a single larger power of 10, as we did in this post. Many early systems did that as well. In a 1966 article in CACM, Mancino [24] summarized the state of the art: “Decimal-to-binary and binary-to-decimal floating-point conversion is often performed by using a table of the powers ( a positive integer) for converting from base 10 to base 2, and by using a table of the coefficients of a polynomial approximation of for converting from base 2 to base 10.” Mancino’s article then showed that the powers-of-10 table could be used for binary-to-decimal as well and also discussed reducing its size.

During the development of IEEE 754 floating-point, Coonen published an implementation guide [7] that defined conversions in both directions using powers of 10 constructed on demand. The powers for can be computed exactly, and then Coonen suggested storing a table containing , , and , so that any power up to can be constructed as the product of at most three multiplications involving at most two inexact values. Coonen computed an approximate using a different approximation to ; if it was off by one, he repeated the process with incremented or decremented by 1. The result was not exact but was provably within a very small error margin, which became IEEE754’s required conversion accuracy. Coonen’s thesis [9] improved on that error margin by changing the table to contain the exceptionally accurate powers , , and , improved the log approximation, and discussed how to use the floating-point hardware’s rounding modes and inexact flag to reduce the error further. In some ways, unrounded scaling is similar to the hardware Coonen shows in this diagram from Chapter 2:

The main difference is that unrounded scaling uses enough precision to avoid any error at all, that some of the chopped bits are discarded entirely rather than feeding into the inexact flag (the sticky bit), and all the details have to be implemented in software instead of relying on floating-point hardware. In an appendix to his thesis, Coonen also defined bignum-based exact conversion routines written in Pascal. (It would be interesting to translate them to C and add them to the benchmarks above!)

1990 was the annus mirabilis of floating-point formatting. In April, Slishman [29] published table-based algorithms for printing and parsing at fixed precision. The algorithms computed 16 additional bits of precision, falling back to a bignum-based implementation only when those 16 bits were all 1’s. This is analogous to unrounded scaling’s check for whether the middle bits are all 0’s and appears to be the earliest analysis of the effect of error carries on the eventual result. (Slishman used a table of powers rounded down, while unrounded scaling uses a table of powers rounded up, so the overflow conditions are inverted.)

In June at the ACM PLDI conference, Steele and White published “How to Print Floating-Point Numbers Accurately” [30] (and Clinger also published “How to Read Floating Point Numbers Accurately” [6], discussed later). Although the paper is mainly cited for shortest-width formatting, Steele and White do discuss fixed-width formatting briefly. Their algorithms use repeated multiplication by 10 instead of a table.

In November, Gay [11] published important optimizations for both printing and parsing but left the basic algorithms unmodified. Gay also published a portable, freely redistributable C implementation. As noted earlier, that implementation is probably one of the most widely copied software libraries ever.

In a 2004 retrospective [31], Steele and White explained:

During the 1980s, White investigated the question of whether one could use limited-precision arithmetic after all rather than bignums. He had earlier proved by exhaustive testing that just 7 extra bits suffice for correctly printing 36-bit PDP-10 floating-point numbers, if powers of ten used for prescaling are precomputed using bignums and rounded just once. But can one derive, without exhaustive testing, the necessary amount of extra precision solely as a function of the precision and exponent range of a floating-point format? This problem is still open, and appears to be very hard.

In 1991, Paxson [28] identified the necessary algorithms to answer that question, but he put them to use only for deriving difficult test cases, not for identifying the precision needed to avoid bignums entirely. My proof post covers that in detail.

It appears that the first table-based exact conversions without bignums were developed by Kenton Hanson at Apple, who documented them on his personal web site in 1997 [15] after retiring. He summarized:

Once this worst case is determined we have shown how we can guarantee correct conversions using arithmetic that is slightly more than double the precision of the target destinations.

Like Slishman’s work at IBM, Hanson’s work unfortunately went mostly unnoticed by the broader research community.

In 2018, Adams [2] published Ryū, an algorithm for shortest-width formatting that used 128-bit tables. After reading that paper (discussed more in the next section), Remy Oudompheng rewrote Go’s fixed-width printer to adopt a table-based single-multiplication strategy. He originally described it as “a simplified version of [Ryū] for printing floating-point numbers with a fixed number of decimal digits,” but he told me recently that he meant only that the code made use of the Ryū paper’s observation that 128-bit precision is generally sufficient for correct conversion. Because the Ryū paper did not address fixed-width printing nor prove the correction of the conversions in that context, Oudompheng devised a new computational proof based on Stern-Brocot tree traversal. Oudompheng’s printer uses Ryū’s fairly complex rounding implementation and expensive exactness computation based on a “divide by five” loop. I wrote Go’s original floating-point printing routines in 2008 but had not kept up with recent advances. In 2025, I happened to read Oudompheng’s printer and realized that the calculation could be significantly simplified using standard IEEE754 hardware implementation techniques, including keeping a sticky bit during scaling. That was the first step down the path to the general approach of unrounded scaling.

I am not sure where IEEE754’s sticky bit originated. The earliest use of it I have found is in Palmer’s 1977 paper introducing Intel’s standard floating-point [27], but I don’t know whether the sticky bit was new in that hardware design.

The unrounded scaling approach to fixed-width printing can be viewed as the same table-based approach described by Mancino [24] and Coonen [7], but using 128-bit precision to produce exact results, as first noted by Hanson [15] and then by Hack [14] and Adams [2].

Shortest-width printing has a related but distinct history. The idea may have begun with Taranto’s 1959 CACM article [33], which considered the problem of converting a fixed-point decimal fraction into a fixed-point binary fraction of the shortest length to reach a given fixed decimal precision. From that paper, Knuth derived the problem of converting between any two bases with shortest output for a fixed precision, publishing it in 1969 as exercise 4.4–3 in the first edition of The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 2: Seminumerical Algorithms [18]. Knuth included his own solution with a reference to Taranto. Knuth’s exercise was not quite the Shortest-Width Printing problem considered above: first, the exercise is about fixed-point fractions, so it avoids the complexity of skewed footprints; and second, the exercise gave no requirement to round correctly, and the solution did not.

Steele and White adapted Knuth’s exercise and solution as the basis for floating-point printing routines in the mid-to-late 1970s. At the time, they shared a draft paper with Knuth, but the final paper was not published until PLDI 1990 [30]. Their fixed-point printing algorithm (FP)³ is Knuth’s solution to exercise 4.4–3, but updated to round correctly. In the second edition of Seminumerical Algorithms [19], Knuth changed the exercise to specify rounding, made Steele and White’s one-line change to the solution, and cited their unpublished draft. In the third edition in 1997 [20], Knuth was able to cite the published paper. In my post “Pulling a New Proof from Knuth’s Fixed-Point Printer”, the section titled “A Textbook Solution” examines Taranto’s, Knuth’s, and Steele and White’s fixed-point algorithms in detail.

Steele and White’s 1990 paper kicked off a flurry of activity focused mainly on shortest-width printing. Their converters were named Dragon2 and Dragon4 (Dragon1 is never described, and they say they omitted Dragon3 for space), which set a dragon-themed naming pattern continued by the ever-more complex printing algorithms that followed. Gay [11] and Burger and Dybvig [5] found important optimizations for special cases but left the core algorithms the same. In their 2004 retrospective [31], Steele and White described those as the only successor papers of note, but that soon changed.

Loitsch [23] introduced the Grisu2 and Grisu3 algorithms at PLDI 2010. Both use a “do-it-yourself floating-point” or “diy-fp” representation limited to 64-bit mantissas to calculate the minimum and maximum decimals for a given floating point input, like in our shortest-width algorithm. 64 bits is not enough to convert exactly, so Grisu2 rounds the minimum and maximum inward conservatively. As a result, it always finds an accurate answer but may not find the shortest one. Grisu3 repeats that computation rounding outward. If its answer also lies within the conservative Grisu2 bounds, that answer must be shortest. Otherwise, a fallback algorithm must be used instead. Grisu3 avoids the fallback about 99.5% of the time for random inputs. Due to the importance of formatting speed in JavaScript and especially JSON, web browsers and programming languages quickly adopted Grisu3.

Andrysco, Jhala, and Lerner introduced the Errol algorithms at POPL 2016 [4]. They extended Loitsch’s approach by replacing the diy-fps with 106-bit double-double arithmetic [10] [18], which empirically handles 99.9999999% of all inputs. They claim to show empirically that “further precision is useless”, and by careful refinement and analysis identified that their final version Errol3 only failed for 45 float64 inputs (!), which they handled with a special lookup table. I am not sure what went wrong in their analysis that kept them from finding that 128-bit precision would have been completely exact.

Picking up a different thread, Abbott et al. [1] published a report in 1999 about IBM’s addition of IEEE754 floating-point to System/390 and repeated a description of Slishman’s algorithms [29]. After reader feedback, Hack [14] analyzed the error behavior and in 2004 published the first proof that 128-bit precision was sufficient for parsing. Nadhezin [26] adapted the proof to printing and formally verified it in ACL2, and Giulietti [12] used that result to create the Schubfach shortest-width printing algorithm in 2018. (In fact Giulietti and Nadhezin showed that 126-bit tables are sufficient, which is important because Java lacks unsigned 64-bit integers.)

Unrounded scaling’s shortest-width algorithm is adapted from Schubfach, which introduced the critical observation that with the right choice of , at most one valid decimal can end in zero. Schubfach’s main scaling operation ‘rop’ can be viewed as a special case of unrounded scaling; Giulietti seems to have even invented the unrounded form from first principles (as opposed to adapting IEEE754 implementation techniques as I did). Schubfach’s rop does not make use of the carry bit optimization, which is the main reason it runs slower than unrounded scaling. The Schubfach implementation was adopted by Java’s OpenJDK after being reviewed by Steele.

Apparently independently of Hack, Nadhezin, and Giulietti, Adams [2] also discovered that 126-bit precision sufficed and used that fact to build the Ryū algorithm in 2018. Ryū does not make use of the carry bit optimization; its rounding and exactness computations are more complex than needed; and it finds shortest-width outputs by repeated division by 10 of the scaled minimum and maximum decimals, which adds to the expense. Even so, the improvement over Grisu was clear, and Adams’s paper was more succinct than Giulietti’s. Many languages and browsers adopted Ryū.

In 2020, Jeon [16] proposed a new algorithm Grisu-Exact, applying Ryū’s 128-bit results to Loitsch’s Grisu2 algorithm. The result does remove the fallback, but it is quite complex. In 2024, Jeon [17] proposed Dragonbox, which applied the Grisu-Exact approach to optimizing Schubfach. The result does run faster but once again adds significant complexity. The unrounded scaling approach to shortest-width printing in this post can also be viewed as a 128-bit Grisu2 like Grisu-Exact or as an optimized Schubfach like Dragonbox, but it is simpler than either. The zero-trimming algorithm in this post is adapted from Dragonbox’s.

Parsing has a much shorter history than printing. As noted earlier, Mancino [24] wrote in 1966 that table-based multiplication algorithms were “often” used for decimal-to-binary conversions. Coonen’s 1984 thesis [9] gave a precise error analysis for the kinds of inexact algorithms that were used until Clinger’s 1990 publication of “How to read floating-point numbers correctly” [6]. Clinger’s approach is to pair an inexact IEEE754 extended-precision floating-point calculation (using a float80 with a 64-bit mantissa) to get an answer that is either the correct float64 or adjacent to the correct float64, and then to check it with a single bignum calculation and adjust upward or downward as needed. Gay [11] quickly improved on this by identifying new special cases and removing the dependence on extended precision (replacing float80s with float64s).

As noted already, Slishman [29] published in 1990 a table-based parser with carry-bit-based fallback to bignums, and then Hack [14] proved in 2004 that 128-bit precision was sufficient to remove the bignum fallback during parsing. While that report inspired Giulietti’s development of the Schubfach printer and Nadhezin’s proof, it does not seem to been used in any actual floating-point parsers besides IBM’s.

In 2020, based on a suggestion and initial code by Eisel, and apparently completely independent of Slishman and Hack, Lemire implemented a fast floating-point parser using a 128-bit table [21] [22] [32]. The Eisel-Lemire algorithm is essentially Slishman’s except with 64 extra bits of precision instead of 16. Lemire used a fallback just as Slishman did, unsure that it was unreachable with 128-bit precision. Mushtak and Lemire [25] published their analog to Hack’s proof a couple years later, allowing the fallback to be removed.

The unrounded scaling approach to parsing is analogous to the approach pioneered by Slishman, Hack, Eisel, Lemire, and Mushtak, just framed more generally and with the carry bit optimization.

Fast Unrounded Scaling

Fast unrounded scaling can be viewed as a combination, generalization, simplification, and optimization of these critical earlier works:

- In 1990, Slishman [29] used the table-based algorithms for fixed-width printing and parsing, with carry bit fallback check, but without enough precision to be completely exact.

- In 2004, Hack [14] improved Slishman’s algorithm by observing that 128-bit precision allowed removing the fallback. It is unclear why Hack considered only parsing and did not generalize to printing.

- In 2010, Loitsch [23] used a table-based algorithm for shortest-width printing but, echoing Slishman, without enough precision to be completely exact. Loitsch used a new approach to check for exactness and trigger a fallback.

- In 2018, Giulietti [12] used a table-based algorithm for shortest-width printing with enough precision to be exact, along with the critical observation about finding formats ending in zero. The only arguable shortcoming was not using the carry bit optimization to halve the cost of the scaling multiplication.

- Also in 2018, Adams [2] used a different table-based algorithm for shortest-width printing and popularized the fact that 128 bits was enough precision to be exact.

- In 2020, Eisel and Lemire [22] rederived a 128-bit form of Slishman’s algorithm. Then in 2023, Mushtak and Lemire [25] proved that the fallback was unreachable using methods similar to Hack’s.

Even though all the necessary pieces are in those papers waiting to be connected, it appears that no one did until now.

As mentioned earlier, I derived the unrounded scaling fixed-width printer as an optimized version of Oudompheng’s Ryū-inspired table-driven algorithm. While writing up that algorithm with a new lattice-reduction-based proof of correctness, I re-read Loitsch’s paper and realized that for shortest-width printing, unrounded scaling enabled replacing Grisu’s approximate calculations of the decimal bounds with exact calculations, eliminating the fallback entirely. Continuing to read related papers, I read Giulietti’s Schubfach paper for the first time and was surprised to find how much of the approach Giulietti had anticipated, including apparently reinventing the IEEE754 extra bits. When I read Lemire’s paper, I was even more surprised to find the carry bit fallback check; the carry bit analysis had played an important role in my proof of unrounded scaling, and this was the first similar analysis I had encountered. (At that point I had not found Slishman’s paper.) That’s when I realized unrounded scaling also applied to parsing. I knew from my proof that Lemire didn’t need the fallback. When I went looking for the code that implemented it in Lemire’s library, I found instead a mention of Mushtak and Lemire’s followup proof. I discovered the other references later.

My contribution here is primarily a synthesis of all this prior work into a single unified framework with a simple explanation and relatively straightforward code. Thanks to all the authors of this critical earlier work, whose shoulders I am grateful to be standing on.

Conclusion

Floating-point printing and parsing of reasonably sized decimals can be done very quickly with very little code. At long last, the dragons have been vanquished.

In this post, I have tried to give credit where credit is due and to represent others’ work fairly and accurately. I would be extremely grateful to receive additions, corrections, or suggestions at rsc@swtch.com.

References

- P. H. Abbott et al., “Architecture and software support in IBM S/390 Parallel Enterprise Servers for IEEE Floating-Point arithmetic”, IBM Journal of Research and Development 43(6), September 1999. ↩

- Ulf Adams, “Ryū: Fast Float-to-String Conversion”, Proceedings of ACM PLDI 2018. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

- Ulf Adams, “Ryū Revisited: Printf Floating Point Conversion”, Proceedings of ACM OOPSLA 2019. ↩ ↩

- Marc Andrysco, Ranjit Jhala, Sorin Lerner, “Printing Floating-Point Numbers: An Always Correct Method”, Proceedings of ACM POPL 2016. ↩ ↩

- Robert G. Burger and R. Kent Dybvig, “Printing Floating-Point Numbers Quickly and Accurately”, Procedings of ACM PPLDI 1996. ↩

- William D. Clinger, “How to Read Floating Point Numbers Accurately”, ACM SIGPLAN Notices 25(6), June 1990 (PLDI 1990). ↩ ↩ ↩

- Jerome T. Coonen, “https://www.computer.org/csdl/magazine/co/1980/01/01653344/13rRUxbCbof”, Computer, 13, January 1980. Reprinted as Chapter 2 of [9]. ↩ ↩

- Jerome T. Coonen, “Underflow and the Denormalized Numbers”, Computer 14, March 1981. ↩

- Jerome T. Coonen, “Contributions to a Proposed Standard for Binary Floating-Point Arithmetic”, University of California, Berkeley Ph.D. thesis, 1984. ↩ ↩ ↩

- T. J. Dekker, “A Floating-Point Technique for Extending the Available Precision”, Numerische Mathematik 18(3), June 1971. ↩

- David M. Gay, “Correctly Rounded Binary-Decimal and Decimal-Binary Conversions”, AT&T Bell Laboratories Technical Report, 1990. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

- Raffaello Giulietti, “The Schubfach way to render doubles”, published online, 2018, revised 2021. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

- Herman H. Goldstein and John von Neumann, Planning and Coding Problems for an Electronic Computing Instrument, Institute for Advanced Study Report, 1947. ↩

- Michel Hack, “On Intermediate Precision Required for Correctly-Rounding Decimal-to-Binary Floating-Point Conversion”, IBM Technical Paper, May 2004. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

- Kenton Hanson, “Economical Correctly Rounded Binary Decimal Conversions”, published online 1997. ↩ ↩

- Junekey Jeon, “Grisu-Exact: A Fast and Exact Floating-Point Printing Algorithm”, published online, 2020. ↩

- Junekey Jeon, “Dragonbox: A New Floating-Point Binary-to-Decimal Conversion Algorithm”, published online, 2024. ↩ ↩ ↩

- Donald E. Knuth, The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 2: Seminumerical Algorithms, first edition, Addison-Wesley, 1969. ↩ ↩

- Donald E. Knuth, The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 2: Seminumerical Algorithms, second edition, Addison-Wesley, 1981. ↩

- Donald E. Knuth, The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 2: Seminumerical Algorithms, third edition, Addison-Wesley, 1997. ↩

- Daniel Lemire, “Fast float parsing in practice”, published online, March 2020. ↩

- Daniel Lemire, “Number Parsing at a Gigabyte per Second”, Software: Practice and Experience 51 (8), 2021. ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

- Florian Loitsch, “Printing Floating-Point Numbers Quickly and Accurately with Integers”, ACM SIGPLAN Notices 45(6), June 2010 (PLDI 2010). ↩ ↩ ↩ ↩

- O. G. Mancino, “Multiple Precision Floating-Point Conversion from Decimal-to-Binary and Vice Versa”, Communications of the ACM 9(5), May 1966. ↩ ↩ ↩

- Noble Mushtak and Daniel Lemire, “Fast Number Parsing Without Fallback”, Software—Pratice and Experience, 2023. ↩ ↩