I like cooking recipes. They’re clean, serene documents where, at some point, one or more utensils enter the stage to perform a task. If you were to write one on how to use AI to augment your work as a technical writer, though, you would have a hard time deciding when and where LLMs come out of the toolbox to aid you. The variety of flavors in which AI presents itself doesn’t help. This is why I’ve come up with a framework that describes applications of the different AI tools at our disposal.

Because AI is useful only when you drive it well, its impact is determined by your inputs and actions. Feed it invalid context and it will spit out garbage; use the wrong tool and you will be babysitting its inference while you could have been doing something far more useful. And no, AI augmentation can’t make you a better technical writer, but it can speed you up and remove obstacles. You might also end up taking on more work, so you’ve got to be careful.

The framework I’m presenting here is my own attempt at organizing the AI toolbox in a way that makes sense for my technical writing workflow and activities. I’ll say here the same I wrote in The Seven-Action Documentation Model: This is not a sequence (good riddance) nor a recipe to be followed to the letter. Rather, it’s an arrangement of tools that might inspire you to do something similar with your own setup.

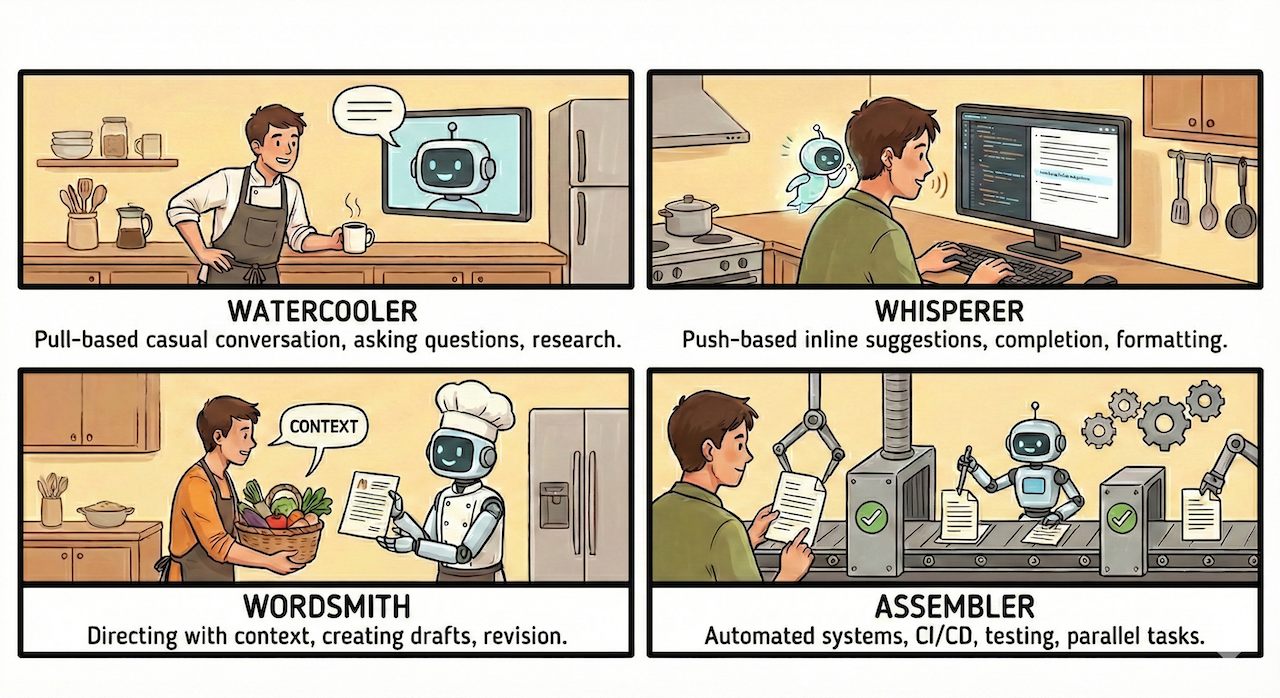

First, you start by having a casual watercooler conversation

You ask, AI answers. This is pull-based: you initiate every exchange through a chat interface. What it’s good for is understanding unfamiliar codebases, rubber-ducking your outline, asking why does this API behave like this, and getting a second opinion on information architecture. LLMs are excellent code explainers. With engineers busy tending to their own work, having an always-available assistant is a boon. For example, I often use AI to prepare better questions for my SMEs.

This homework that talks back is done best in web interfaces like Gemini’s or Claude’s, with the proviso that those tools must be approved first for usage by your IT department. Claude projects or Gemini’s huge context window allow you to shove truckloads of data into the LLMs cauldron: your words then become the scoop with which you give shape to the output. I’ve used this system to draft strategic plans and internal documentation, editing and correcting when needed.

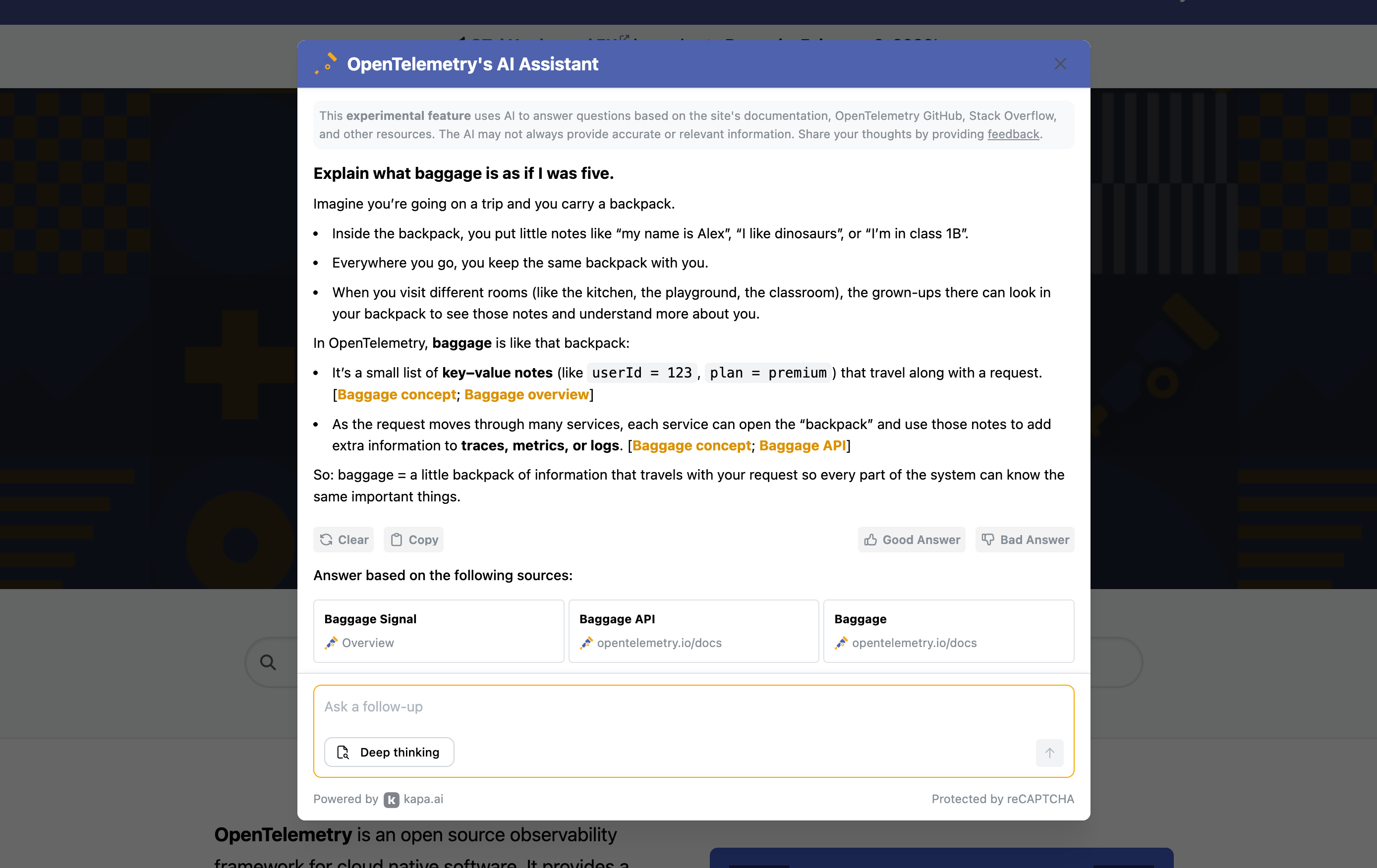

Consider building an AI-powered assistant that explains configuration snippets in human-readable form. One of my colleagues built a proof of concept for OpenTelemetry configs, testing different approaches and evaluating accuracy. The goal was to speed up the path to understanding. You can also use AI in watercooler mode to research blogs, knowledge bases, and forums for customer use cases related to features you’re documenting, turning scattered feedback into docs priorities.

Then you let the machine whisper useful words to your ears

AI anticipates what you need, then you approve with a keystroke. This mode lives in your editor, surfacing inline suggestions, tab completion, and context-aware drafting from your local files. It handles those moments of writing where you know roughly what comes next but don’t want to type it. It’s the kind of menial work I don’t miss doing, like macros, but without having to record them. This is letting AI help make you faster and make fewer errors without letting it take the wheel.

The whisperer mode excels at pattern recognition. Whether it’s reformatting tables, fixing links, converting markup, or applying repetitive edits across files, IDEs like Cursor or Copilot can detect patterns in your edits and save you hours every week, especially when allowed to index your repository. If you’ve ever spent an afternoon fixing the same formatting issue across fifty files, you’ll understand the appeal of an AI that notices what you’re doing and offers to do the rest.

Cursor’s auto completion model, Tab, is quite powerful, although Copilot got better, so make sure to often test what the market offers. When introducing this feature to writers, remind them that tab complete can be snoozed, postponed, or turned off when necessary. If inline suggestions feel intrusive at first, most editors let you adjust the delay before they appear, or turn them off entirely. It’s worth experimenting until you find a rhythm that feels like assistance rather than interruption.

At some point, you provide context to the wordsmith to shape it into drafts

You provide context, constraints, and intent, and the AI generates drafts you’ll shape. This mode covers first drafts, restructuring existing content, generating code samples, and boilerplate of all kinds. But it also covers revision, feeding AI an existing draft and asking it to tighten, match a style guide, or restructure. Creation and revision are the same relationship, just with different inputs, and always backed up by the context and knowledge you’ve built into your IDE by editing docs yourself.

The quality of what comes out is a function of how well you’ve prepared what goes in, which is why treating context curation as a skill worth developing pays off quickly. Templates and examples work as prompt scaffolding; your docs model becomes an AI briefing. For context delivery, LLM-friendly Markdown files and docs-as-data packaging help you feed LLMs the right material in formats they handle well. This mode demands the most from you as context curator.

“To get good results you need to provide context, you need to make the tradeoffs, you need to use your knowledge. It’s not just a question of using the context badly, it’s also the way in which people interact with the machine. Sometimes it’s unclear instructions, sometimes it’s weird role-playing and slang, sometimes it’s just swearing and forcing the machine, sometimes it’s a weird ritualistic behavior. Some people just really ram the agent straight towards the most narrow of all paths towards a badly defined goal with little concern about the health of the codebase."

Build a prompt library for common docs tasks. We’ve experimented at work with instruction files that improve page openings (frontmatter, H1s, intros, summaries), taking content types into account. Use a local LLM to generate metadata at scale, like page abstracts for semantic search, SEO-optimized meta descriptions, and tags. Another good investment are content types and templates that LLMs can use to ensure consistency when creating first drafts. Your public style guide? Don’t throw it away, it’s exactly the kind of context that generative AI needs.

Finally, you set your own robotic assembly line of checks, rewrites, and tests

The next step is designing systems that run without continuous prompting and that can perform various operations in parallel. This mode covers CI/CD integration, automated style checks, MCP servers that validate code samples, and subagents that test procedures or check links. It also includes using AI to build these systems (if you’ve ever built agent instructions using an LLM, you know what I mean). You’re letting it run an assembly line, but without falling into agent psychosis.

Where MCP provides a stable way for LLMs to interact with databases and tools, agents (or subagents) are the most interesting right now, especially in the wake of Claude Skills: you define helpers that can take care of specific tasks, like testing your docs or checking the style. A big pro of subagents is that they have their own context windows, so that you don’t have to “pollute” the main context with auxiliary ops. Check out Sarah Deaton’s Testing docs IA with AI agents for ideas.

Create an MCP server that checks docs for consistency and accuracy against your production documentation using semantic search. We built one at work that connects to Elasticsearch for exactly this purpose. Another project worth pursuing: automate your docs maintenance workflow entirely through GitHub Actions, reducing manual steps for simple doc updates. If you’re ambitious, explore a more robust code sample testing framework with key datasets (this is on my to-do list).

You’ll often find yourself switching between modes

You might start in watercooler mode to understand a feature, move to wordsmith to generate a first draft, drop into whisperer as you refine and format, then let the assembler validate before publishing. Sometimes you go straight to whisperer mode because you already know what you’re writing. Other times you stay in watercooler mode for hours because the feature is gnarly and you need to think it through before touching a draft. That’s OK. You’ll do this a lot.

The framework doesn’t tell you which mode is best. That depends on the task, the risk, and your skill level. What matters is being intentional about which situation you’re in and what that demands from you. Watercooler mode requires good questions. Whisperer asks for pattern awareness. Wordsmith asks for context curation. Assembler asks for system design. Each mode has its own craft. When developing an AI strategy for your docs you’ll want to care for all of them.

Going back to the initial simile: You can stock your kitchen with every utensil imaginable and still burn the pasta. The four modes I’ve described are ways of thinking about which tool to reach for and when, but they’re useless without someone who knows what they’re cooking. That’s a human writer. If you need a reminder, read my previous post.