There are stories about cracked engineers. The dude who rewrote the whole google maps in a weekend. John Carmack. Elon Musk. The 10x or 10^n x engineer is a well established concept and seems to be pointing at a real thing. High agency people who can completely lock in and achieve incredible feats of programming or engineering by just having an intuitive understanding of the system and its components .

We also keep hearing from tech bigshots like Jensen Huang and Sam Altman that as well as AI, biotech1 is going to be the next big thing and they're super excited about it.

Despite working around the industry in various disciplines for like a decade, and the whole pitch being that we can "program" cells to do what we want, I have heard no tales much less encountered anyone who fits the cracked category in biotech. I'm talking about a go to person who has crazy output and can crack any problem.

(Side note: the closest person at least close to this space is probably Shulgin, who was great, however my read is that he didn't have some massive 10x chemistry/pharmacology skill but a DEA license, a sense of adventure, and a pharmacopia of low hanging psychedelic fruit).

Sure, I have met people who are in the lab until midnight grinding out experiments by putting things in and out of incubators and adding chemicals to Eppendorf tubes (and no disrespect, I admire the grind and sometimes you do just need to Do The Thing). There are people who seem to be relatively successful serial biotech entrepreneurs (although I wouldn't be too confident that part of this isn't some lucky early hits and then grad student selection effects). There are people who *gag* publish a lot of *retch* high impact papers. There's technicians who are the go to for instruments and hardware fixes. There are PCR wizards 2 . There just doesn't seem to be the same category of 10x biotech scientist3 in terms of actually making and releasing Something People Want.

Why is this?

We cracked the central dogma. Biology is programmed in DNA. The DNA makes the RNA and the RNA makes the proteins, and the proteins do all the stuff. We can read and write DNA. So what's the issue?

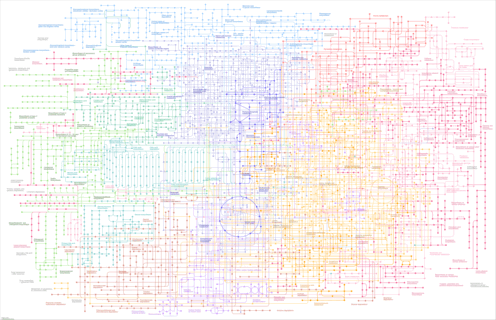

The issue is a bunch of bullshit that happens in between each of those steps that each encompass entire disciplines of study in and of themselves. The central dogma is a nice story but pasted on top of it you have oodles of variables and moving parts, all interacting with one another with no overarching design that has been hobbled together by billions of slightly lucky accidents over a few billion years. This may simply be a system that no single human mind can actually grok sufficiently well to engineer it precisely.

The programming problem is "why is the computer doing what I told it to do rather than what I want it to do". The biotech problem is "why is this cell doing things that maximised the comparative fitness of its genes in a wildly different environment, features of which I am not even aware of let alone able to manipulate, and not what I want it to do".

The cells are going to take as long as they take to grow. The OODA loop for actually learning things is much slower than computer programming. Even hardware engineering the cycle time is set by constraints one can somewhat push on and manipulate and there's optionality for swapping and tweaking components. In biology the cells are gonna grow how they grow. Heaven forbid you actually want to study a living organism, or even possibly a human.

To be clear, in reality biotech cycle time is also affected by levers one could certainly speed up (if there exists an analytics department that always has extra capacity and runs samples immediately I am yet to hear of it). I think there's also something of a mindset/culture issue on how long things should take in wet labs that is pretty ingrained and hard to shake. Which brings me to the next issue, which is probably affected by the first two.

How does someone with that cracked dog in them start computer programming? Maybe they want to solve a problem, and start figuring out how to automate it with some simple scripts. They find it fun, keep tinkering. Start building things. People like the things, and use them. Make whatever they want, they can lock in and grind all night. Eventually they have a portfolio of stuff to show a FAANG recruiter or a prototype to show YC and then someone will pull out a few sacks with dollar signs on them and now they’re a cracked 10x software engineer.

What about physical engineering? Here I'll admit that there is some more limits, but probably you get a circuit board, or a raspberry pi to stick into things. You start tinkering, building stuff at home or maybe at a highschool or university workshop. You're not building Starship on a weekend but you can go build *something*. You can explore the space and for lots of things the only limit is your imagination and how much 3d printer resin you have.

OK so how do you start bioengineering? You take a high school or undergrad course, they hand you a protocol, and you do it. If it doesn't work you did it wrong. Then....that's it until the next lab course. They give you another protocol and you follow it, and so on for a semester. Maybe there's a little bit of creative freedom if you're lucky, but you're basically doing someone else's ideas until post PhD, and even then you need someone with their own lab to sign off and let you come try stuff out. Likely you also need some grant money of your own too (the procurement of which is a whole other kettle of risk averse perverse incentives). There is basically no straightforward way to fuck around and make a thing in biotech (iGem is probably the closest, and that still needs a whole team and structure and supervisor to sign off).

Some personal background:

I figure I am probably top 1% in 'amount of fucking around and trying stuff' during an early lab career in biotech. During my PhD, 95 % of my lab time was working on the nitty gritty molecular pharmacology of the receptor the drug company sponsoring me was interested in. I learned a lot, I independently made some crucial decisions in what turned a pretty good project with some genuinely novel receptor pharmacology stuff. The drug company was happy. I was very much working on a project someone else wanted done though.

As for the other 5%, my supervisor was very chill, so as a side project I ordered some weird Russian drugs I'd read about on Slate Star Codex to throw at a few receptors and see if anything stuck4.

As a post-doc I managed to somehow stumble into an even more chill supervisor. A true old school, Oxford in the 70s, heavy drinking, hates administrators with a burning passion, polyglot professor. Here I started being able to try my own ideas and was told that I should spend 20 % of my time on long shot high payoff ideas. This is pretty abnormal in a wet lab! On top of having the greenlight from the boss I still only really did this because I didn't really care about my publication record having decided long ago I wasn't going to stick in academia. If I was, then I would have been way more on rails grinding our papers.

The point is I was super lucky in which labs I landed in, twice (!), and I still spent a huge chunk of time where I was working on other peoples projects until I was well past my PhD.

I think this selection effect is pretty strong. Intuitively it feels like "crackedness" probably correlates pretty strongly with "likes working on a system I can grok" and "major motivation is making a thing". Combined with a low base rate (1/10000?, 1/100 000?) of cracked engineers in the undergraduate population, even if people come into the universities just as interested in biotech as computer science or programming, we pretty easily get to ~0 cracked biotechnologists on this alone.

Maybe?

There's a few forces pushing in that direction. Automation + cloud labs gives people the power to skip the whole lab skills section and focus on designing smart experiments and looking for insights, but the cycle time and cost is still super high. LLMs lets people skip reading lots of low information density papers and get the basics down more quickly, and is generally a much smoother process of learning a field. This may motivate some cashed up tech types to switch into biotech and make a new and better working environment that attracts the cracked (Arc kind of seems like it's aiming for this, and Astera Institute is doing stuff pushing in this direction too). Price to get setup with the lab basics and some cool toys (an Opentrons, some mini plate readers) is falling, and a few biohackers are trying to build cool stuff in their garage. We're still nowhere near "raspberry pi and a 3d printer" level costs though.

AI could well render this all kind of moot. If it it is just about keeping a complex enough metabolic map in your head and coming up with experiments to poke at it until you can grok it, then this seems a task kind of well suited to AGI (with either robots or cooperative humans). Apparently item 1 on the AGI to do list will be “increase the rate of scientific discovery” so we may well get a whole lot of cracked biotechnologists all at once in, let’s see um, 2030.