In my previous post, I showed that frontier LLMs struggle with text-based quests from Space Rangers 2: Russian video game form 2004 that any teenager can complete. The most surprising result? The quest that breaks models most consistently is rated as “20% difficulty” by the game itself, the easiest category.

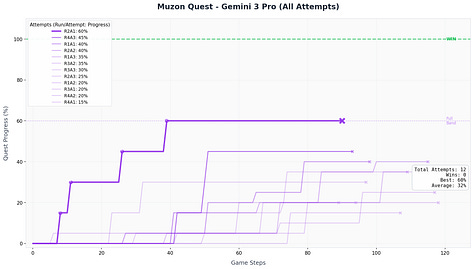

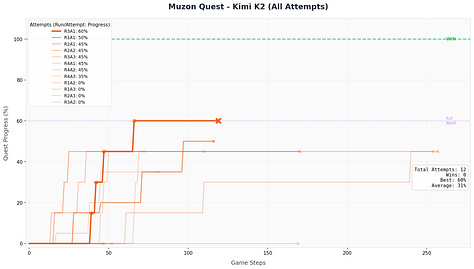

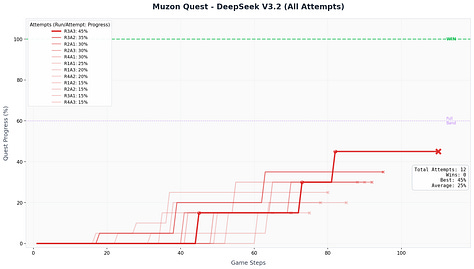

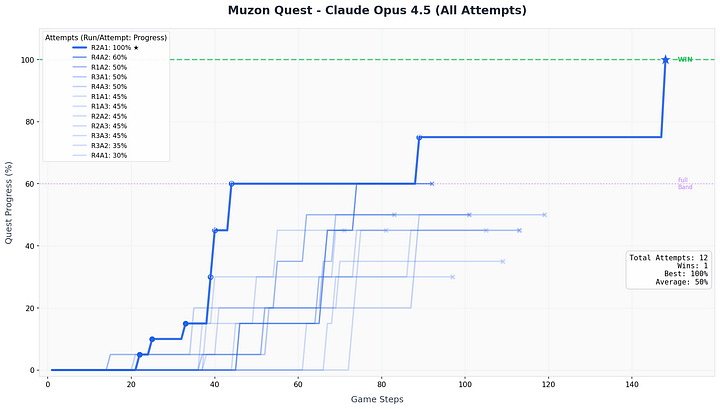

It’s called ”Music Festival” (Muzon in Russian), and Claude Opus 4.5 Thinking was the only model to complete the quest, succeeding once out of 12 attempts. Every other model failed all 12 tries.

This post zooms in on this single quest to understand: What makes a “simple” social reasoning task so hard for models that ace complex math and coding problems?

You’re a space ranger who lands on a planet hosting an annual galactic music festival. Your mission: assemble a rock band in 3 days and win first place. The setup sounds straightforward:

Find 4 musicians: Guitarist, Keyboardist, Bass Player, Drummer

Buy a song and rehearse

Perform at the festival

A 14-year-old playing this quest will typically:

Explore the quest locations and talk to everyone

Get rejected by musicians

Figure out what’s missing and get it

Recruit the band, attend the festival

Total time: 15-30 minutes, maybe 2 attempts if they miss something.

For LLMs, this becomes a 100-150 step challenge where success requires maintaining a coherent plan across dozens of location visits, NPC conversations, and resource decisions.

Space Rangers quests are implemented as state machines. Each quest has ~100-300 locations (states) connected by conditional transitions (choices). Every location tracks game state: your inventory, stats like money and mood, time of day, and flags for events you’ve triggered. Each choice you make either progresses the state (”Recruit guitarist” → guitarist joins band) or blocks you (”You need tattoos” → remain in same state).

Multiple paths lead to victory. In Music Festival, you could recruit musicians in different orders, buy different songs, use different strategies to earn money. But certain paths are gated: you can’t recruit the Keyboardist until you’ve asked about musicians at the Tattoo Parlor, and you can’t approach the Bass Player while drunk.

The quest ends in either WIN (win the festival), FAIL (run out of time/money/die), or rare edge cases like abandoning the mission. This structure makes it perfect for benchmarking: success is binary, paths are deterministic once you understand the prerequisites, and humans solve it reliably.

Each musician has unstated prerequisites. The game doesn’t tell you upfront, you discover them through rejection:

Guitarist (on Long Street, daytime)

├─ Requires: Any Tattoo

└─ Requires: Guitar Strings

Drummer (at Rock Club, daytime)

├─ Requires: Ear Piercing

└─ Requires: Drumsticks

Keyboardist (in Pool Room, nighttime)

├─ Requires: Asking about musicians at Tattoo Parlor (unlocks him)

└─ Requires: Get him drunk (100r) OR beat him at pool

Bass Player (at Pub, nighttime)

├─ Requires: Drunkenness = 0 (must be sober!)

└─ Requires: "Politeness in Human Society" book (50r)Let me show you what happened when I ran 5 frontier models through this quest, 12 attempts each (4 runs × 3 attempts with reflection).

Progress is calculated as: 15% per recruited band member (60% for full band) + 5% per prerequisite item (tattoo, piercing, etiquette book, song) + 20% for winning the festival.

From 12 attempts, most models managed to recruit a full band (60% progress)

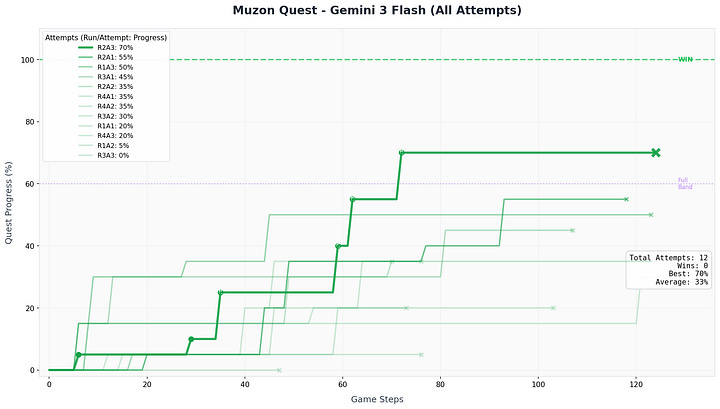

Here are trajectories from each model under investigation. Each line is one attempt. Steeper slopes = faster progress. Plateaus = stuck trying the same failed actions repeatedly.

Over 60 attempts with reflections between failures, models succeeded exactly once. They consistently fail to act on social feedback, even when they correctly identify the problem afterward.

The number of possible trajectories is large, making individual failures hard to trace. But certain patterns emerged consistently across runs, even when models occasionally "solved" the same problem in different runs.

Ignoring explicit requests:

The drummer says: “A real rocker should have a piercing.”

Claude’s next 4 actions: visit recording studio, visit recording studio, visit recording studio, visit pub. The tattoo parlor—which offers piercings for 20 rockarollars—was one click away at every step. Claude never returned to the drummer’s requirement. The drummer never joined.

Over-theorizing instead of listening:

The guitarist says: “Bring me new strings and I’ll join your band.” Gemini’s reasoning:

“My ‘Average singer’ skill level is insufficient to impress a musician with an elite instrument.”

It invented a theory about skill requirements. The actual answer: buy strings for 50r on the laptop. No skill check involved.

Correct reflection, same mistake:

After failing, Claude’s reflection is spot-on:

“I should have gotten the piercing immediately when the drummer requested it.”

Next attempt: visits recording studio 3 times. Never gets the piercing. Same failure, same reflection, no behavioral change.

The AI community has been playing whack-a-mole with benchmarks. ARC-AGI was supposed to test “human-like general fluid intelligence” through visual puzzles that LLMs couldn’t solve. Then o3 beat it. The response? ARC-AGI 2 with bigger grids. When models beat that, ARC-AGI 3 with 60×60 grids, testing [imho] context management more than somewhat useful reasoning capabilities.

The pattern is clear: when models solve a benchmark, we make the grids bigger. There is another class of problems that any teenager can do, that is hard for LLMs even though it does not require:

PhD-level knowledge (like GPQA)

Synthetic pattern recognition (like ARC-AGI)

Massive context windows (like 60×60 grids)

They require:

Following explicit instructions

Updating behavior based on feedback

Executing a self-identified correction

Models ace the hard benchmarks: Claude Opus scores 75% on SWE-bench. Gemini 3 Pro hits 90% on GPQA. Yet they fail at “the drummer wants a piercing” → “go get a piercing.”

The benchmark is open source. I tested 4 other quests in my previous blog-post and LLMs seemed to have better luck with them (even though they are rated with higher difficulty). There ~30 other quests I have not benchmarked yet.