The drawbacks of nuclear fission power are well-known. Fission power plants create long-lived radioactive waste, produce plutonium which could potentially be reprocessed into nuclear weapons, and release decay heat which requires continuous cooling to prevent a core meltdown.

Fusion, by contrast, is often presented as the “holy grail of energy”. Brian Potter, in his well-researched article “Will We Ever Get Fusion Power?”, restates fusion power’s supposed advantages:

Unlike coal or gas, which rely on exhaustible sources of fuel extracted from the earth, fusion fuel is effectively limitless. A fusion reactor could theoretically be powered entirely by deuterium (an isotope of hydrogen with an extra neutron), and there’s enough deuterium in seawater to power the entire world at current rates of consumption for 26 billion years.

Fusion has many of the advantages of nuclear fission with many fewer drawbacks. Like fission, fusion only requires tiny amounts of fuel: Fusion fuel has an energy density (the amount of energy per unit mass) a million times higher than fossil fuels, and four times higher than nuclear fission. Like fission, fusion can produce carbon-free “baseload” electricity without the intermittency issues of wind or solar. But the waste produced by fusion is far less radioactive than fission, and the sort of “runaway” reactions that can result in a core meltdown in a fission-based reactor can’t happen in fusion.

In theory, this is all true.

But in practice, fusion reactors (if they worked) would have very few advantages compared to fission reactors, and significant disadvantages. In particular, fusion power plants are far less powerful than fission power plants, and far more expensive. Fusion reactors also require materials which are either extremely scarce or, at best, could only power human civilization for thousands (or, arguably, millions) of years. Fission reactors, by contrast, could realistically power humanity for billions of years.

Let’s assume, for sake of argument, that fusion reactors ultimately work as designed.

To be clear, I think it’s extremely unlikely this happens. In particular, it seems highly probable that fusion power plants would either destroy themselves from the inside (due to disruptions, heat flux, and/or neutron damage) too quickly to be viable as a power plant, be unable to create enough fuel inside the reactor (due to tritium retention), and/or run into any number of possible roadblocks inherent in a project of such engineering complexity and experimental uncertainty.

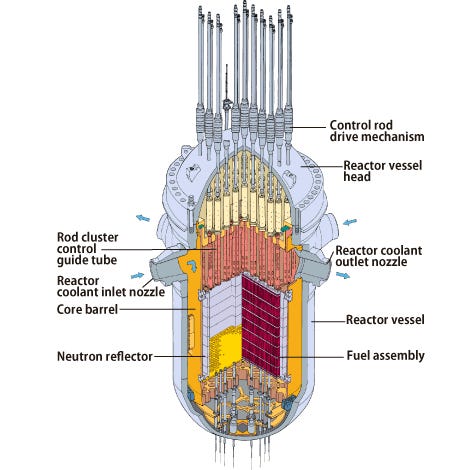

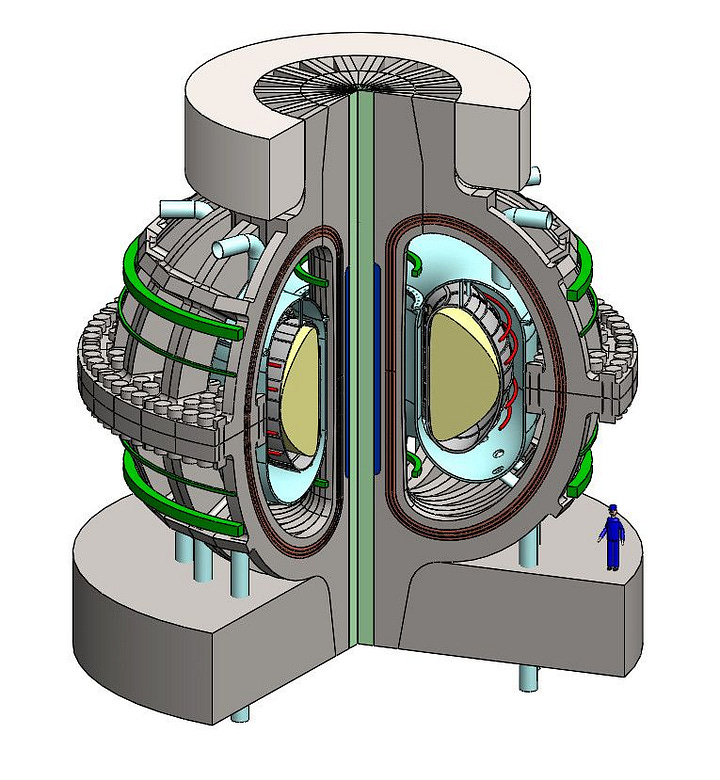

But assuming that fusion reactors do work as designed, we can then compare the power produced by the leading fusion reactor concept, the tokamak, to the most common fission reactor design, the pressurized-water reactor (PWR).

Fission reactors, it turns out, produce about 100 megawatts of power per meter cubed (100MW/m³) in the reactor core.

Specifically, a typical PWR produces about 3300 MW of thermal energy in a cylindrical reactor core of about 3.5m diameter and 3.5m length (33m³).

Even the highest power density fusion reactor designs, however, produce only about 5 megawatts of power per meter cubed (5MW/m³) in the plasma core.

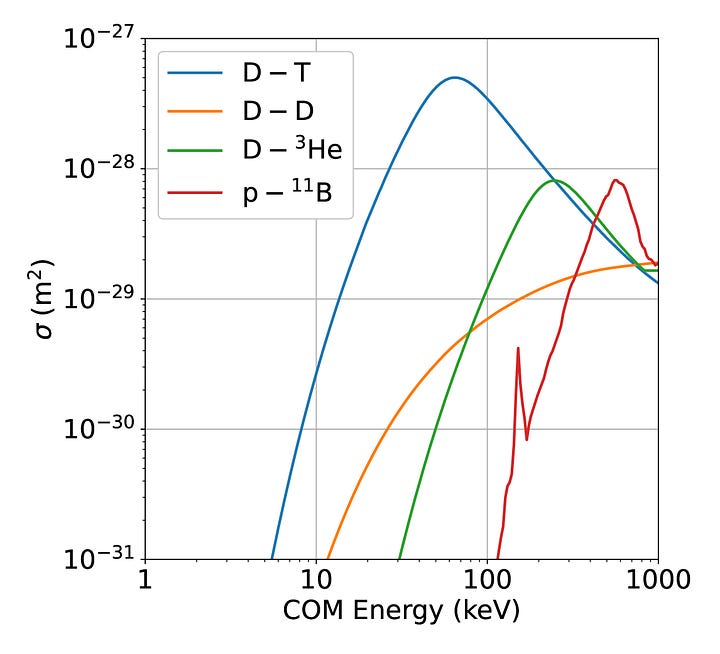

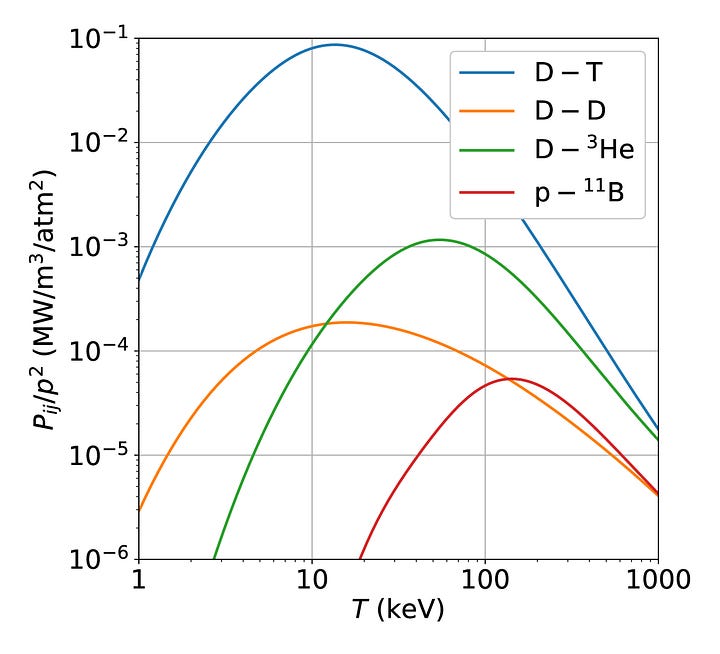

The formula for the power density inside a fusion reactor is 0.1 MW/m³ times the plasma pressure (in atmospheres) squared. This can be derived from the fusion cross-section data by making a few simple assumptions (approximately steady-state plasma, optimal temperature, optimal fuel mix). Given a plasma pressure of 7 atmospheres, a plausible target for future power plants, the power density would be about 5 MW/m³.

So fusion reactors, if they worked, would be about 20 times less powerful than fission reactors.

Though the energy density (energy per unit mass) of fusion fuel is four times higher than nuclear fission, the power density (power per unit volume) of a fusion reactor is much lower than a fission reactor. In other words, fusion is great if you want to build a thermonuclear warhead, but if you want to build a power plant, you’ll get a lot more power from fission.

Fusion reactors share most of the disadvantages of fission reactors in terms of waste, weaponization risk, and safety. Fortunately, these disadvantages seem to be less (sometimes much less) of a concern in fusion reactors compared to fission reactors. For example, although fusion reactors would be ideal for producing weapons-grade plutonium, clandestine plutonium production would be easier to detect in fusion reactors than fission reactors.

In practice, however, the biggest issue (by far) with fission reactors has been their cost.

Unfortunately, fusion reactors project to be significantly more expensive than fission reactors, even when using extremely optimistic cost projections.

To understand how the cost of a fusion reactor compares to a fission reactor, we’ll make some simple back-of-the-envelope calculations.

The (overnight) cost of a 1 GW nuclear fission power plant in the U.S. and Europe is roughly $10B. Of this $10B, roughly 10% ($1B) goes towards the reactor core, and 90% goes towards everything else (containment building, coolant pumps, safety systems, steam turbines and power generation equipment, supporting systems and infrastructure, concrete foundations and civil works, project design, procurement and construction management, etc).

So, as a back-of-the-envelope estimate, the cost of a fission reactor core is about $30M/m³, but the reactor core is only about 10% of the cost of the power plant.

To estimate the cost of a fusion reactor, we can use the MIT/CFS estimates for the cost of the ARC fusion reactor concept. They estimate, for a reactor with a plasma volume of 141m³, a cost of $7.5B.1 This gives a cost per volume of about $50M/m³.

But as we know, fusion reactors would produce about 20x less power per volume than fission plants. So per unit power, a fusion reactor core would cost roughly 30 times more than a fission reactor core.2

This means that, even if the 100% of the cost of a fusion power plant were the reactor core, a fusion power plant would still cost roughly 3 times as much as a fission power plant.

To be clear, I think this significantly underestimates the true cost of a fusion power plant, for a few reasons.

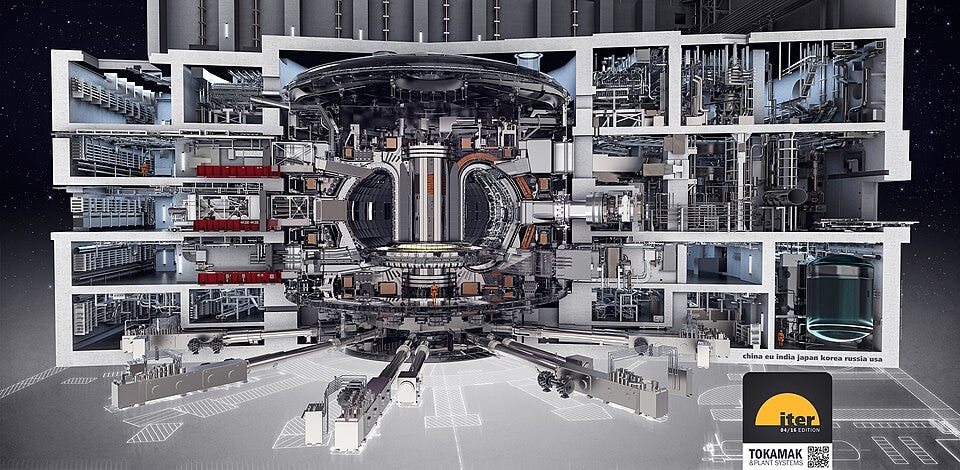

First, in fusion power plants, like fission power plants, the reactor core is only one small part of the overall plant. For example, extracting the fusion fuel from the ITER fusion reactor will require (see above) a six-story building the length of a football field filled with industrial equipment for processing radioactive tritium. Furthermore, inside the ITER tokamak hall (see below) the reactor core is surrounded by a vast network of various auxiliary systems.3

As we’ve seen, in fission power plants these sorts of auxiliary systems (plus the engineering design cost and various miscellaneous costs) make up about 90% of the total cost of the plant.

Fortunately, there are good reasons to think that these auxiliary costs might be lower in fusion plants, because they (presumably) wouldn’t be subject to the same regulations.4 I’m not entirely sold on this argument—these costs might be lower, but they also might be higher because of the additional auxiliary systems (blanket, heating, tritium processing) not found in fission power plants. In either case, the auxiliary and miscellaneous costs would undoubtedly add billions of dollars per gigawatt to the overall cost of a fusion power plant.

Second, empirically fusion reactors have, like fission power plants and most other large infrastructure projects, tended to cost significantly more than initially estimated. ITER, for example, was initially estimated to cost $5B. Over time, however, the official estimated cost has ballooned to $25B, and the U.S. DOE has projected that ITER could ultimately cost as much as $65B.

It is illustrative to compare the cost estimates of NuScale, a leading nuclear fission startup, to Commonwealth Fusion Systems (CFS), the leading nuclear fusion startup. NuScale initially estimated a cost of $7B per GW in 2015. However, by 2023 their estimate had tripled to $21B per GW, leading to the cancellation of their demonstration power plant. It is reasonable to expect that CFS, which in 2015 estimated a cost of $39.5B per GW (not including auxiliary costs) for their demonstration plant, would see similar cost increases.5

I don’t have an accurate estimate for the true cost of a fusion power plant—nobody does—but (if it worked) I expect it would cost roughly 10 times as much as an equivalent fission power plant.6

Fusion is often described as a “virtually limitless” energy source.

For reactors using the deuterium-deuterium (D-D) reaction, this is true: there is enough deuterium in seawater to power our civilization for 26 billion years.7

But the D-D reaction has a big problem: it barely produces any power.

This is because our earlier formula for the power density of a fusion reactor (0.1 MW/m³ times the plasma pressure in atmospheres squared) is only valid for reactors using deuterium-tritium (D-T) fuel. Reactors using D-D or D-He³ fuel (see above graph) have power densities around 100 times lower.8 In other words, tokamak power plants using D-D fuel would have power densities about 2000 times lower than fission reactors.

Anyone attempting to build a fusion reactor with “alternative” fuels such as D-D will either need to create extraordinarily high pressures, build an extraordinarily large reactor, or produce extraordinarily little power. In sci-fi fantasies, we can imagine fusion reactors powered by limitless D-D fuel confined at extremely high pressure. But in the real world, physicists have no credible pathway to confining plasmas at such high pressures. Barring some unlikely moonshot breakthrough, we seem to be stuck with D-T fusion.

Unfortunately, the D-T reaction is far from “limitless”.

In a 2011 paper “Is nuclear fusion a sustainable energy form?”, three German9 physicists performed some simple calculations comparing the materials required for D-T fusion with their estimated global resources. They concluded, ultimately, that a fusion “power plant could not be described as sustainable.”

The problem is that tritium doesn’t exist in nature, and so fusion reactors need to produce tritium inside the reactor using (a) lithium, which reacts with neutrons to produce tritium, and (b) a neutron multiplier, of which beryllium or lead are the only options under serious consideration.

Lithium, beryllium, and lead each have potentially significant long-term resource limitations.

Of the three, lithium is the most abundant. The earth’s crust contains about 100 Mt of lithium, enough to power the entire world at current rates of energy consumption for roughly 10,000 years. In seawater, however, there is enough lithium to power human civilization for about 20 million years. Beryllium is an extremely rare element, with global resources estimated at about 0.1 Mt. Though beryllium is a common choice of neutron multiplier—the ARC fusion reactor concept, for example, uses beryllium—there is only enough of it on earth to power the entire world for about 200 years. Lead, the alternative to beryllium, is fortunately much more common; there is enough of it to power the world for about 200,000 years.

So for how long could fusion power human civilization?

As we’ve seen, the answer to this question is a bit complicated. Though there is enough deuterium on earth to theoretically power humanity for 26 billion years, the extremely low power density of D-D fusion makes it difficult to imagine (outside of sci-fi scenarios) creating power plants fueled purely with deuterium. In practice, fusion power plants would be constrained by the availability of neutron multipliers, of which lead is the most abundant and could power humanity for about 200,000 years. In theory it might be possible to create fusion power plants without the neutron multipliers lead and beryllium, in which case lithium would become the limiting resource. In that case, there is enough lithium in seawater to power humanity for roughly 20 million years.

What about for fission?

By recycling nuclear waste in breeder reactors, there is enough uranium on earth for fission power plants to power humanity for over 4 billion years.

So, depending on whether lithium or lead were to become the limiting resource in fusion power plants, nuclear fission could power human civilization either 200 times or 20,000 times longer than nuclear fusion. In either case, nuclear fission is clearly the more sustainable option.