I built an ARM64 assembly lexer (well, I generated one from my own parser generator, but this post is not about that) that processes Dart code 2x faster than the official scanner, a result I achieved using statistical methods to reliably measure small performance differences. Then I benchmarked it on 104,000 files and discovered my lexer was not the bottleneck. I/O was. This is the story of how I accidentally learned why pub.dev stores packages as tar.gz files.

The setup

I wanted to benchmark my lexer against the official Dart scanner. The pub cache on my machine had 104,000 Dart files totaling 1.13 GB, a perfect test corpus. I wrote a benchmark that:

- Reads each file from disk

- Lexes it

- Measures time separately for I/O and lexing

Simple enough.

The first surprise: lexing is fast

Here are the results:

| Metric | ASM Lexer | Official Dart |

|---|---|---|

| Lex time | 2,807 ms | 6,087 ms |

| Lex throughput | 402 MB/s | 185 MB/s |

My lexer was 2.17x faster. Success! But wait:

| Metric | ASM Lexer | Official Dart |

|---|---|---|

| I/O time | 14,126 ms | 14,606 ms |

| Total time | 16,933 ms | 20,693 ms |

| Total speedup | 1.22x | - |

The total speedup was only 1.22x. My 2.17x lexer improvement was being swallowed by I/O. Reading files took 5x longer than lexing them.

The second surprise: the SSD is not the bottleneck

My MacBook has an NVMe SSD that can read at 5-7 GB/s. I was getting 80 MB/s. That is 1.5% of the theoretical maximum.

The problem was not the disk. It was the syscalls.

For 104,000 files, the operating system had to execute:

- 104,000

open()calls - 104,000

read()calls - 104,000

close()calls

That is over 300,000 syscalls. Each syscall involves:

- A context switch from user space to kernel space

- Kernel bookkeeping and permission checks

- A context switch back to user space

Each syscall costs roughly 1-5 microseconds. Multiply that by 300,000 and you get 0.3-1.5 seconds of pure overhead, before any actual disk I/O happens. Add filesystem metadata lookups, directory traversal, and you understand where the time goes.

I tried a few things that did not help much. Memory-mapping the files made things worse due to the per-file mmap/munmap overhead. Replacing Dart's file reading with direct FFI syscalls (open/read/close) only gave a 5% improvement. The problem was not Dart's I/O layer, it was the sheer number of syscalls.

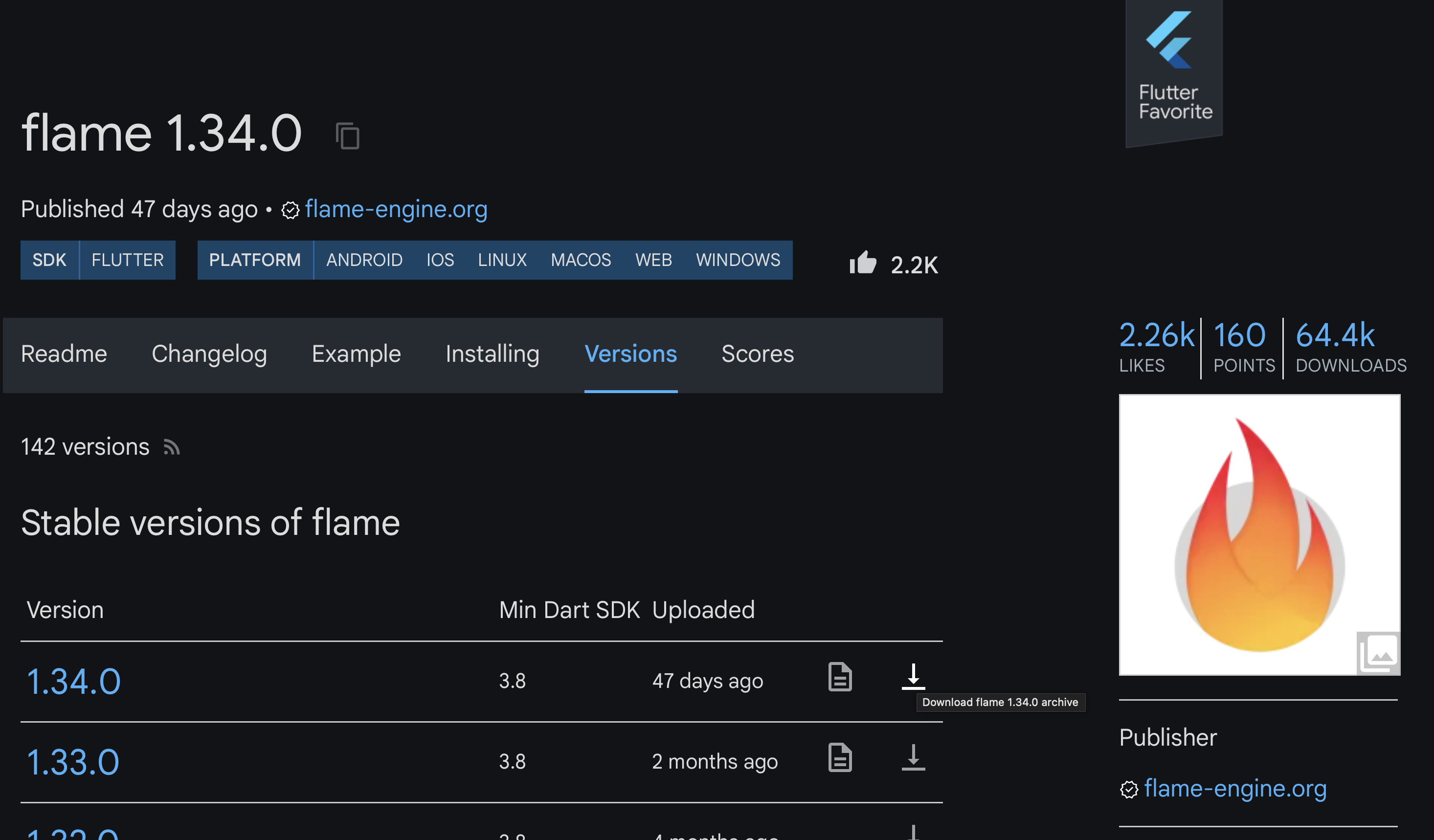

The hypothesis

I have mirrored pub.dev several times in the past and noticed that all packages are stored as tar.gz archives. I never really understood why, but this problem reminded me of that fact. If syscalls are the problem, the solution is fewer syscalls. What if instead of 104,000 files, I had 1,351 files (one per package)?

I wrote a script to package each cached package into a tar.gz archive:

104,000 individual files -> 1,351 tar.gz archives

1.13 GB uncompressed -> 169 MB compressed (6.66x ratio)

The results

| Metric | Individual Files | tar.gz Archives |

|---|---|---|

| Files/Archives | 104,000 | 1,351 |

| Data on disk | 1.13 GB | 169 MB |

| I/O time | 14,525 ms | 339 ms |

| Decompress time | - | 4,507 ms |

| Lex time | 2,968 ms | 2,867 ms |

| Total time | 17,493 ms | 7,713 ms |

The I/O speedup was 42.85x. Reading 1,351 sequential files instead of 104,000 random files reduced I/O from 14.5 seconds to 339 milliseconds.

The total speedup was 2.27x. Even with decompression overhead, the archive approach was more than twice as fast.

Breaking down the numbers

I/O: 14,525 ms to 339 ms

This is the syscall overhead in action. Going from 300,000+ syscalls to roughly 4,000 syscalls (open/read/close for 1,351 archives) eliminated most of the overhead.

Additionally, reading 1,351 files sequentially is far more cache-friendly than reading 104,000 files scattered across the filesystem. The OS can prefetch effectively, the SSD can batch operations, and the page cache stays warm.

Decompression: 4,507 ms

gzip decompression ran at about 250 MB/s using the archive package from pub.dev. This is now the new bottleneck. I did not put much effort into optimizing decompression, an FFI-based solution using native zlib could be significantly faster. Modern alternatives like lz4 or zstd might also help.

Compression ratio: 6.66x

Source code compresses well. The 1.13 GB of Dart code compressed to 169 MB. This means less data to read from disk, which helps even on fast SSDs.

Why pub.dev uses tar.gz

This experiment accidentally explains the pub.dev package format. When you run dart pub get, you download tar.gz archives, not individual files. The reasons are now obvious:

- Fewer HTTP requests. One request per package instead of hundreds.

- Bandwidth savings. 6-7x smaller downloads.

- Faster extraction. Sequential writes beat random writes.

- Reduced syscall overhead. Both on the server (fewer files to serve) and the client (fewer files to write).

- Atomicity. A package is either fully downloaded or not. No partial states.

The same principles apply to npm (tar.gz), Maven (JAR/ZIP), PyPI (wheel/tar.gz), and virtually every package manager.

The broader lesson

Modern storage is fast. NVMe SSDs can sustain gigabytes per second. But that speed is only accessible for sequential access to large files. The moment you introduce thousands of small files, syscall overhead dominates.

This matters for:

- Build systems. Compiling a project with 10,000 source files? The filesystem overhead might exceed the compilation time.

- Log processing. Millions of small log files? Concatenate them. Claude uses JSONL for this reason.

- Backup systems. This is why rsync and tar exist.

What I would do differently

If I were optimizing this further:

- Use zstd instead of gzip. 4-5x faster decompression with similar compression ratios.

- Use uncompressed tar for local caching. Skip decompression entirely, still get the syscall reduction.

- Parallelize with isolates. Multiple cores decompressing multiple archives simultaneously.

Conclusion

I set out to benchmark a lexer and ended up learning about syscall overhead. The lexer was 2x faster. The I/O optimization was 43x faster.

Addendum: Reader Suggestions

Linux-Specific Optimizations

servermeta_net pointed out two Linux-specific approaches: disabling speculative execution mitigations (which could improve performance in syscall-heavy scenarios) and using io_uring for asynchronous I/O. I ran these benchmarks on macOS, which does not support io_uring, but these Linux capabilities are intriguing. A follow-up post exploring how I/O performance can be optimized on Linux may be in order.

king_geedorah elaborated on how io_uring could help with this specific workload: open the directory file descriptor, extract all filenames via readdir, then submit all openat requests as submission queue entries (SQEs) at once. This batches what would otherwise be 104,000 sequential open() syscalls into a single submission, letting the kernel process them concurrently. The io_uring_prep_openat function prepares these batched open operations. This is closer to the "load an entire directory into an array of file descriptors" primitive that this workload really needs.

macOS-Specific Optimizations

tsanderdev pointed out that macOS's kqueue could potentially improve performance for this workload. While kqueue is not equivalent to Linux's io_uring (it lacks the same syscall batching through a shared ring buffer), it may still offer some improvement over synchronous I/O. I have not benchmarked this yet.

macOS vs Linux Syscall Performance

arter45 noted that macOS may be significantly slower than Linux for certain syscalls, linking to a Stack Overflow question showing open() being 4x slower on macOS compared to an Ubuntu VM. jchw explained that Linux's VFS layer is aggressively optimized: it uses RCU (Read-Copy-Update) schemes liberally to make filesystem operations minimally contentious, and employs aggressive dentry caching. Linux also separates dentries and generic inodes, whereas BSD/UNIX systems consolidate these into vnode structures. This suggests my benchmark results on macOS may actually understate the syscall overhead problem on that platform relative to Linux, or alternatively, that Linux users might see smaller gains from the tar.gz approach since their baseline is already faster.

Is it really the syscalls?

ori_b pushed back on the claim that syscall overhead is the bottleneck. On a Ryzen machine, entering and exiting the kernel takes about 150 cycles (~50ns). Even at 1 microsecond per mode switch, 300,000 syscalls would account for only 0.3 seconds of the 14.5-second I/O time. That is roughly 2%. The remaining time likely comes from filesystem metadata lookups, inode resolution, directory traversal, and random seek latency. Even NVMe SSDs have ~50-100 microseconds of latency per random read, and 300,000 random reads at that latency would account for most of the measured I/O time. So the framing might be more precisely stated as "per-file overhead" rather than "syscall overhead" since the expensive part is the work happening inside each syscall, not the context switch itself. It is also worth noting that ori_b's numbers are from a Linux Ryzen machine, where syscalls are faster than on macOS (as discussed above), adding another variable. I do not currently have tooling to break down where the 14.5 seconds actually goes, so this is something I want to investigate in the future.

Avoiding lstat with getdents64

stabbles pointed out that when scanning directories, you can avoid separate lstat() calls by using the d_type field from getdents64(). On most popular filesystems (ext4, XFS, Btrfs), the kernel populates this field with the file type directly, so you do not need an additional syscall to determine if an entry is a file or directory. The caveat: some filesystems return DT_UNKNOWN, in which case you still need to call lstat(). For my workload of scanning the pub cache, this could eliminate tens of thousands of stat syscalls during the directory traversal phase, before even getting to the file opens.

Go Monorepo: 60x Speedup by Avoiding Disk I/O

ghthor shared a similar experience optimizing dependency graph analysis in a Go monorepo. Initial profiling pointed to GC pressure, but the real bottleneck was I/O from shelling out to go list, which performed stat calls and disk reads for every file. By replacing go list with a custom import parser using Go's standard library and reading file contents from git blobs (using git ls-files instead of disk stat calls), they reduced analysis time from 30-45 seconds to 500 milliseconds. This is a 60-90x improvement from the same fundamental insight: avoid per-file syscalls when you can batch or bypass them entirely.

Haiku's packagefs

smallstepforman described how Haiku OS solves this problem at the operating system level. Haiku packages are single compressed files that are never extracted. Instead, the OS uses packagefs, a virtual filesystem that presents the contents of all activated packages as a unified directory tree. Applications see normal paths like /usr/local/lib/foo.so, but the data is actually read from compressed package files in /system/packages. Install and uninstall are instant since you are just adding or removing a single file, not extracting or deleting thousands. This eliminates the syscall overhead entirely at the OS level rather than working around it at the application level. Haiku is an open-source OS recreating BeOS, known for its responsiveness and clean design. While not mainstream, its package architecture demonstrates that the "extract everything to disk" model most package managers use is not the only option.

SquashFS for Container Runtimes

stabbles suggested SquashFS with zstd compression as another alternative. It is used by various container runtimes and is popular in HPC environments where filesystems often have high latency. SquashFS can be mounted natively on Linux or via FUSE, letting you access files normally while the data stays compressed on disk. When questioned about syscall overhead, stabbles noted that even though syscall counts remain high, latency is reduced because the SquashFS file ensures files are stored close together, benefiting significantly from filesystem cache. This is a different tradeoff than tar.gz: you still pay per-file syscall costs, but you gain file locality and can use standard file APIs without explicit decompression. One commenter warned that when mounting a SquashFS image via a loop device, you should use losetup --direct-io=on to avoid double caching (the compressed backing file and the decompressed contents both being cached), which can reduce memory usage significantly.

SQLite as an Alternative

tsanderdev mentioned that this is also why SQLite can be much faster than a directory with lots of small files. I had completely forgotten about SQLite as an option. Storing file contents in a SQLite database would eliminate the syscall overhead while providing random access to individual files, something tar.gz does not offer.

This also explains something I have heard multiple times: Apple uses SQLite extensively for its applications, storing structured data and metadata in SQLite databases rather than as individual files. snej clarified that Apple's SQLite-based APIs (CoreData, SwiftData) are database APIs with an ORM and queries, not filesystem simulations. The Photos app, for example, uses SQLite for metadata and thumbnails, but the actual photos remain as individual files. Still, the principle holds for the data that is stored in SQLite: if 100,000 files on a modern Mac with NVMe storage takes 14 seconds to read, imagine what it was like on older, slower machines. The syscall overhead would have been even more punishing. For workloads where random access to many small records is needed, SQLite avoids those syscalls entirely. This is worth exploring.

Skip the Cleanup Syscalls

matthieum suggested a common trick used by batch compilers: never call free, close, or munmap, and instead let the OS reap all resources when the process ends. For a one-shot batch process like a compiler (or a lexer benchmark), there is no point in carefully releasing resources that the OS will reclaim anyway.

GabrielDosReis added a caveat: depending on the workload, you might actually need to call close, or you could run out of file descriptors. On macOS, you can check your limits with:

$ launchctl limit maxfiles

maxfiles 256 unlimited

$ sysctl kern.maxfilesperproc

kern.maxfilesperproc: 61440

The first number (256) is the soft limit per process, the second is the hard limit. kern.maxfilesperproc shows the kernel's per-process maximum. With 104,000 files, skipping close calls would exhaust even the maximum limit. dinosaurdynasty noted that the low default soft limit is a historical artifact of the select() syscall, which can only handle file descriptors below 1024. Modern programs can simply raise their soft limit to the hard limit and not worry about it.

There is even a further optimization: use a wrapper process. The wrapper launches a worker process that does all the work. When the worker signals completion (via stdout or a pipe), the wrapper terminates immediately without waiting for its detached child. Any script waiting on the wrapper can now proceed, while the OS asynchronously reaps the worker's resources in the background. I had not considered this approach before, but it seems worth trying.

Dwedit noted that on Windows, a similar optimization is to call CloseHandle from a secondary thread, keeping the main thread unblocked while handles are being released.

Linker Strategies for Fast Exits

MaskRay added context about how production linkers handle this exact problem. The mold linker uses the wrapper process approach mentioned above, forking a child to do all the work while the parent exits immediately after the child signals completion. This lets build systems proceed without waiting for resource cleanup. The --no-fork flag disables this behavior for debugging. The wild linker follows the same pattern.

lld takes a different approach with two targeted hacks: async unlink to remove old output files in a background thread, and calling _exit instead of exit to skip the C runtime's cleanup routines (unless LLD_IN_TEST is set for testing).

MaskRay notes a tradeoff with the wrapper process approach: when the heavy work runs in a child process, the parent process of the linker (typically a build system) cannot accurately track resource usage of the actual work. This matters for build systems that monitor memory consumption or CPU time.

Why pub.dev Actually Uses tar.gz

Bob Nystrom from the Dart team clarified that my speculation about pub.dev's format choice was partially wrong. Fewer HTTP requests and bandwidth savings definitely factored into the decision, as did reduced storage space on the server. Atomicity is important too, though archives do not fully solve the problem since downloads and extracts can still fail. However, it is unlikely that the I/O performance benefits (faster extraction, reduced syscall overhead) were considered: pub extracts archives immediately after download, the extraction benefit only occurs once during pub get, that single extraction is a tiny fraction of a fairly expensive process, and pub never reads the files again except for the pubspec. The performance benefit I measured only applies when repeatedly reading from archives, which is not how pub works.

This raises an interesting question: what if pub did not extract archives at all? For a clean (non-incremental) compilation of a large project like the Dart Analyzer with hundreds of dependencies, the compiler needs to access thousands of files across many packages. If packages remained in an archive format with random access support (like ZIP), the syscall overhead from opening and closing all those files could potentially be reduced. Instead of thousands of open/read/close syscalls scattered across the filesystem, you would have one open call per package archive, then seeks within each archive. Whether the decompression overhead would outweigh the syscall savings is unclear, but it might be worth exploring for build systems where clean builds of large dependency trees are common.

Use dart:io for gzip Instead of package:archive

Simon Binder pointed out that dart:io already includes gzip support backed by zlib, so there is no need to use package:archive for decompression. Since dart:io does not support tar archives, I used package:archive for everything and did not think of mixing in dart:io's gzip support separately. Using dart:io's GZipCodec for decompression while only relying on package:archive for tar extraction could yield better performance. I will try this approach when I attempt to lex a bigger corpus.

TAR vs ZIP: Sequential vs Random Access

vanderZwan pointed out that ZIP files could provide SQLite-like random access benefits. This highlights a fundamental architectural difference between TAR and ZIP:

TAR was designed in 1979 for sequential tape drives. Each file's metadata is stored in a header immediately before its contents, with no central index. To find a specific file, you must read through the archive sequentially. When compressed as tar.gz, the entire stream is compressed together, so accessing any file requires decompressing everything before it. The format was standardized by POSIX (POSIX.1-1988 for ustar, POSIX.1-2001 for pax), is well-documented, and preserves Unix file attributes fully.

ZIP was designed in 1989 with a central directory stored at the end of the archive. This directory contains offsets to each file's location, enabling random access: read the central directory once, then seek directly to any file. Each file is compressed individually, so you can decompress just the file you need. This is why JAR files, OpenDocument files, and EPUB files all use the ZIP format internally.

| Aspect | TAR | ZIP |

|---|---|---|

| Random access | No (sequential only) | Yes (central directory) |

| Standardization | POSIX standard | PKWARE-controlled specification |

| Unix permissions | Fully preserved | Limited support |

| Compression | External (gzip, zstd, etc.) | Built-in, per-file |

There seems to be no widely-adopted Unix-native format that combines random access with proper Unix metadata support. TAR handles sequential access with full Unix semantics. ZIP handles random access but originated from MS-DOS and has inconsistent Unix permission support. What we lack is something like "ZIP for Unix": random access with proper ownership, permissions, extended attributes, and ACLs.

The closest answer is dar (Disk ARchive), designed explicitly as a tar replacement with modern features. It stores a catalogue index at the end of the archive for O(1) file extraction, preserves full Unix metadata including extended attributes and ACLs, supports per-file compression with choice of algorithm, and can isolate the catalogue separately for fast browsing without the full archive. However, dar has not achieved the ubiquity of tar or zip.

For my lexer benchmark, random access would not help since I process all files anyway. But for use cases requiring access to specific files within an archive, this architectural distinction matters.

Block-Based Compression

cb321 pointed out that there is a middle ground between uncompressed archives (random access but large) and fully compressed streams (small but sequential). Standard gzip compresses everything into a single block, so accessing any byte requires decompressing from the beginning. BGZF (Blocked GNU Zip Format), developed by genomics researchers for tools like samtools, compresses data in independent 64KB blocks. Each block is a valid gzip stream, so the file remains compatible with standard gunzip, but with an index you can seek directly to any block and decompress just that portion. This allows random access to multi-gigabyte genome files without decompressing terabytes of data. Zstd offers a similar seekable format with better compression ratios and faster decompression. For tar archives, combining block-based compression with an external file offset index could provide random access to individual files while still benefiting from compression.

RE2C: A Faster Approach to Lexer Generation

rurban mentioned that RE2C generates lexers that are roughly 10x faster than flex. The key difference is architectural: while flex generates table-driven lexers that look up transitions in arrays at runtime, RE2C generates direct-coded lexers where the finite automaton is encoded directly as conditional jumps and comparisons. This eliminates table lookup overhead and produces code that is both faster and easier for CPU branch predictors to handle.

RE2C also supports computed gotos (via the -g flag), a GCC/Clang extension that compiles switch statements into indirect jumps through a label address table. For lexers with many states, this can significantly reduce branch mispredictions. Other optimizations include DFA minimization and tunnel automaton construction.

My ARM64 assembly lexer currently uses a table-driven approach, so exploring direct-coded generation is an interesting avenue. Another option is profile-guided optimization: compiling the lexer to LLVM IR and using PGO to optimize hot paths based on real Dart code patterns, something I mentioned as a future direction in my LLVM parser benchmarking post. Part of my lexer's speed advantage over the official Dart scanner likely comes from simplicity: my lexer is pure, maintaining only a stack for lexer states across multiple finite automata, while the Dart scanner must construct a linked list of tokens, handle error recovery, and manage additional bookkeeping. Isolating how much of the performance difference comes from architecture versus feature set is something I want to investigate further.

Game Engine Archives: MPQ and CASC

Iggyhopper pointed out that Blizzard Entertainment solved this same problem decades ago with their MPQ archive format (Mo'PaQ, short for Mike O'Brien Pack). First deployed in Diablo in 1996, MPQ bundles game assets (textures, sounds, models, level data) into large archive files with built-in compression, encryption, and fast random access via hash table indexing. The format was used across StarCraft, Diablo II, Warcraft III, and World of Warcraft. At GDC Austin 2009, Blizzard co-founder Frank Pearce revealed that WoW contained 1.5 million assets, a number that has only grown across subsequent expansions. In 2014, Blizzard replaced MPQ with CASC (Content Addressable Storage Container) starting with Warlords of Draenor, adding self-maintaining integrity checks and faster patching. The same principle from this blog post applies: bundling assets into large archives avoids the per-file overhead that would make loading millions of individual files impractical for a real-time game.

Amdahl's Law

fun__friday pointed out that the main takeaway is to measure before you start optimizing something, referencing Amdahl's law. This is a fair point, and this blog post is a textbook illustration of it: when lexing accounts for only ~17% of total execution time, even a 2x improvement in lexing yields only a 1.22x overall speedup. The theoretical maximum speedup from improving just the lexing component is bounded by the fraction of time spent on everything else. Measure first, optimize second.

That said, from a "business" standpoint it makes sense to focus on the largest bottlenecks (by following, e.g., the Critical path method) and those parts that take up the most time. However, software can be reused, and making a single component faster can have significant benefits to other consumers of that component. A faster lexer benefits not just this benchmark but every tool that uses it: formatters, linters, analyzers, compilers. I think our software community thrives in part because we don't strictly follow the common sense that business optimization dictates.

The Limits of Profiling

Ameisen expanded on the "measure first" advice with an important caveat: measuring can itself be very difficult or misleading. Three cases stand out. First, "death by a thousand cuts," where many small inefficiencies individually appear as noise in a profiler but collectively add up to significant overhead. No single hotspot dominates, so there is nothing obvious to fix. Second, indirect task dependencies, where speeding up one component has cascading benefits that a profiler will not attribute to it. Ameisen gives the example of a sprite resampling mod where a faster hashing algorithm not only helps the render thread directly but also keeps worker threads fed with data sooner, reducing overall latency in ways that are invisible in a flat profile. Third, profilers show what is slow, not why it is slow. Cache invalidations from false sharing are a classic example: the profiler points at a slow memory access, but the actual cause (another thread writing to the same cache line) is hidden. The thing causing the slowdown and the thing made slow by it are different, and only the latter shows up in the profile. In a follow-up comment, Ameisen shared concrete examples: concurrent workers running 30% slower because their output data needed its own cache line but did not have it (false sharing), and a render thread gaining a 20% speedup from removing a safety branch that always passed, because the branch triggered an undocumented CPU pipeline flush when followed by a locked instruction. Neither issue showed up meaningfully in a profiler.