So here’s the pitch: you’re going to entomb yourself in a small cell for the rest of your life and contemplate God. You’ll never touch another human, feel the sun on your skin, or shit anywhere but a bucket. One small caveat, you may keep a cat. Got it? Good. Let’s go.

It feels inevitable to receive looks of bewilderment — and occasionally horror —when I wax rhapsodically about the lives of anchoresses, as I am sometimes wont to do.1 And look, I get it. To our modern brains there is something very cult-y about sealing oneself away for God, declaring yourself dead to the world and occupying a shoebox cell for decades. But bear with me. Because the life of an anchoress is not just grim solitude. It was rich and textured, intentional stillness in the midst of a community. She was a living saint. In many ways, choosing the anchoritic life was radically freeing.

So let's get our bearings. Once a woman decided she might seek the life of an anchoress, she needed to secure two things: the approval of her local bishop and sufficient funding from a patron who would cover her expenses (a girl's gotta eat, after all). Patrons came in the form of nobility, parishes, abbeys, even the Crown. Local communities were incentivized to host an anchoress, as they drew visitors and boosted the local economy. If the bishop determined the woman in question was sufficiently funded and understood the reality of her decision, she could take her place in the cell.

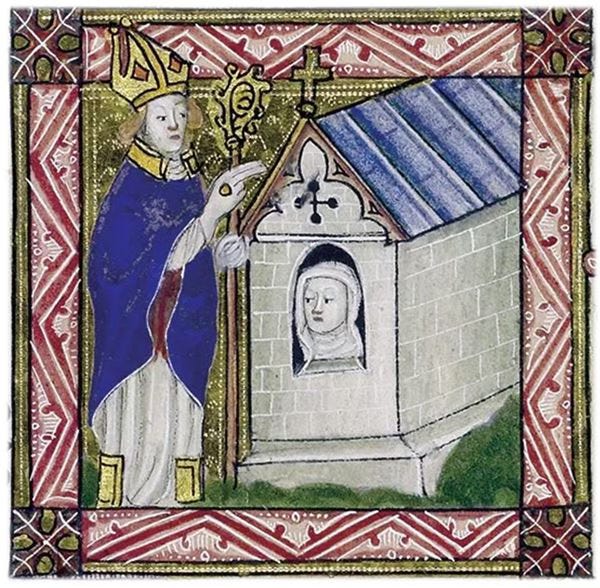

A ceremony called the Enclosure officially declared the new anchoress dead to the world. It was then she was locked in — either by bricks or a sealed door. Some cells came with a grave already dug in the center of the floor. Others were instructed by their bishop to dig the dirt with their nails each day, scratching away at the floor that would one day bear their corpse. Talk about memento mori.

Anchorholds, the small cell attached to the church where the anchoress resided, were not entirely cut off from the world. A small window called a squint allowed for a view of the altar and the ability to take communion. Another window, large enough to pass a chamber pot (the aforementioned bucket), allowed the anchoress to communicate with her maids. It was advised that an anchoress keep two maids — one younger, who could tend to the anchoress's physical needs, and one older who could join her in prayer and generally keep an eye on unwanted visitors. Finally, there was a window to the outside world. This was kept closed with a curtain, preferably dark in color, to obscure her face and those outside.

At last, our anchoress is safely entombed. Now what? An anchoress was meant to spend her days in prayer and contemplation. No longer of the world, her peripheral existence acted as an intermediary between regular people and God. She would give advice on both religious and secular matters. Though she remained separate from the world outside, the world could not but help coming to her. In this strange dichotomy the anchoress existed — in total solitude yet entirely enmeshed in the community around her.

The anchoress was not without guidance for how she should spend her days. A work titled Ancrene Wisse, or Guide for Anchoresses, is an anonymous manual written in the early 13th century. Originally written for three sisters who had chosen this austere lifestyle, the guide became the ultimate rule book for the anchoress. The rules were very specific and (honestly?) quite sensible. They included the dont’s, such as:

No eating meat or fat

No fasting without permission from the bishop

No speaking on Fridays

No loving your window too much (aka, don’t get too gabby with the townsfolk)

And some great do’s as well:

Shave your head or cut it very short

Wear big, warm shoes in the winter (just not to bed)

Blood-let four times a year

Wash as often as you like

Keep no animal but a cat. “Ye, mine leove sustren, bute yef neod ow drive ant ower meistre hit reade, ne schulen habbe na beast bute cat ane” / “My dear sisters, unless need drives you and your director advises it, you must not have any animal except a cat"

You may be wondering, what happens if you get cold feet? Perhaps shocking to no one, there are several cases from history of anchoresses who fled their cells. In 1329, the Bishop of Winchester granted Christine Carpenter the right to become enclosed at St James church in Shere. By 1331 Christine had fled her cell and tried to rejoin society. News of her broken vow spread quickly and faced with ex-communication, she petitioned the pope to be forgiven. And entombed again. Permission was given and this time instead of a door to her cell, they bricked her right up. She died in her cell at an unknown date.

There is something about the anchoress that captures our attention; confuses us, challenges us, makes us need to adjust our perspective on why a woman might choose to do this. Let’s return to that figure I mentioned earlier — anchoresses outnumbered anchorites four to one in the 13th century. Why is this? For one, let’s consider that religious vocations for women were staggeringly less available than those for men. An anchoritic life provided several freedoms that women were not otherwise afforded at the time. In fact, we have this lifestyle to thank for the earliest surviving English works by a woman. Julian of Norwich wrote Revelations of Divine Love, a book of Christian mystical devotions, while in her cell.

No one was forcing a woman to become an anchoress. The choice was hers, one that had to be argued to the bishop to prove her devotion. At a time when choices for women were severely limited and lifetimes cut short by frequent childbirth, an anchoritic life allowed for rare feminine agency.

It’s no small wonder anchoresses pop up in current culture. They mystify! They intrigue! They confuse the hell out of us modern folk!2 But their lives allow us a peek into the medieval mind.

So the next time you’re spouting facts about anchoresses — and I’m counting on you, please, spread the good word — don’t forget to mention how this lifestyle was one of the most radical things a woman could do in the Middle Ages.