I spent a week in Trinidad and Tobago (which I’ll call “TT”), mostly in Port of Spain (the capital) and the northern mountain region of Trinidad.

My major source this time is the Area Handbook for Trinidad and Tobago commissioned by the U.S. Army in 1975 (which I’ll refer to as the “Handbook”). If I have learned anything from these blog posts, it’s that U.S. government-commissioned country surveys are great sources. I imagine that if I was a diplomat sent to Trinidad and Tobago in 1975 and I knew absolutely nothing about the country, this would get me up to speed. It’s easy to read, perfect level of detail, comprehensive, if rather blunt in its pre-PC era evaluations of cultural norms. Other sources are linked within.

Overview

Population (2024) – 1,508,927

Population Growth Rate (2023) – 0.25%

Size – 1,980 square miles (about 2/3rds the size of Delaware)

GDP (nominal, 2023) – $28.1 billion (similar to Iceland)

GDP growth rate (2023) – 2.1%

GDP per capita nominal (2023) – $19,731

GDP per capita PPP (2023) – $28,458

Inflation rate (2020-2024)- 0.3%-8.7%

Biggest export – Ammonia

Median age (2024) – 37.2

Life expectancy (2024) – 76.5

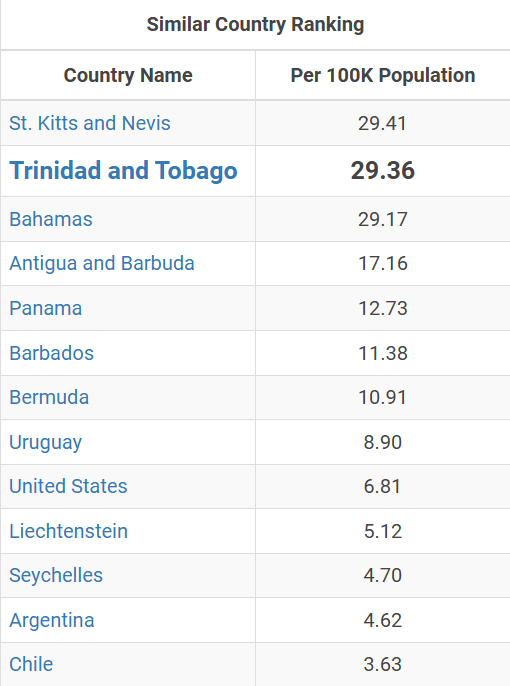

Murder rate (2023) – 39.5 per 100,000 (#7 worldwide)

Founded – 1962

Ethnicity (2011) – 35% Indian, 34% black, 23% multiracial

Religion – 63% Christian, 24% Hindu

Corruption Perceptions Index – #76/180

Index of Economic Freedom – #79/184

On the Ground

The Caribbean has always been a weak part of my geography. I can picture a map of Europe or Asia in my head and identify every country, but the Caribbean is a pile of random little island countries and territories that I can’t keep straight. Where is St. Kitts? What is a Turks and Caicos? How is Dominica not the same thing as the Dominican Republic? Does Martinique exist?

Naturally, I assumed Trinidad and Tobago was just another one of these things. I assumed it was two islands that used to have cash crop plantations and are still inhabited by the descendants of slaves. I assumed there would be some shady offshore banking, a bunch of beaches and resorts, and horrible crime wherever there weren’t tourists.

This turned out to be about 70% accurate. The inaccurate part is that TT is a step above almost every other Caribbean country and territory in terms of development and wealth. Jamaica, the Bahamas, the Dominican Republic, and most of the rest of them are basically third world countries with tourist resorts and financial enclaves where the police enforce draconian security standards for the sake of economic survival. But TT is a straight-up developing country, more akin to Mexico, Thailand, or Eastern Europe. There are a few skyscrapers, plenty of Western restaurant chains, and some decent (if scary) roads. It’s difficult to explain, but just from walking and driving around, you can feel things are a little bit wealthier, higher quality, and overall better in TT than in the rest of the region.

The huge exception to all that is crime. Before going to Guyana, every forum, website, and person I talked to told me that Guyana is incredibly dangerous and I should never flash a hint of jewelry or cell phone while walking around or I’ll be instantly mugged. Once I was in Guyana and told a few locals that I was going to TT later, every one of them (three separate instances) told me it was vastly more dangerous than Guyana and I really needed to watch my ass there. At the very least, I was far more likely to be shot in TT compared to stabbed in Guyana.

At one point in TT, I drove to Fort George to get a beautiful view overlooking the capital, Port of Spain:

I later told a pair of locals I did this and they were shocked. I asked why. They told me that it’s one of the most dangerous parts of TT and I shouldn’t have gone there at all. I told them that I drove there at 10 AM in broad daylight on a Tuesday. They said that didn’t matter, that I easily could have been stopped in my car and mugged at any time. These two – a husband and wife who ran a successful business – also said that crime was the single worst part of living in TT and the primary reason they were trying to emigrate. Using 2021 numbers:

Maybe I’m lucky, maybe I have good awareness, maybe I just look broke when I travel, but yet again, I encountered no crime despite walking around a decent chunk of Port of Spain and driving around a decent chunk of the country. I was out late a few nights, but mostly stuck to popular areas.

Let me say a cheesy traveller thing: the best thing about TT is that it feels like the most pure, local, authentic culturally Caribbean country there is. It’s actually weird how untouristy TT is. There is one hostel in the entire country, there are very few souvenir shops (and seemingly all are run by Chinese people), and I saw almost no tourist infrastructure at all. Again, I just assumed every Caribbean island would be packed with tourists, but to my knowledge, I didn’t see a single one throughout my entire week. I’d bet that I saw some Caribbean tourists, but no white people at least.

Granted, I wasn’t in touristy areas, and I only went to one beach for ten minutes because I don’t care about beaches. My original plan was to split the time between Trinidad (the big island with most of the population and all the industry) and Tobago (the small island with the best beaches and touristy stuff), but there was some sort of festival and the ferry was fully booked so I was stuck on Trinidad. But still, in the Bahamas or Jamaica, even though the tourists are confined to their enclaves, you can feel their presence. Those countries are basically designed around tourists, if not for them; TT definitely isn’t.

I spent most of my time in TT driving around northern Trinidad which consists of jungle-covered mountains that fall into the sea. It’s amazing. It’s beautiful. It’s almost empty. Two of my four big hikes were some of the best I have done in years. One consisted of walking in a river upstream:

Another ended at a plane crash:

I saw the “Bamboo Cathedral:”

And on the way back I saw a squad of TT police training in it:

Another hike was to the summit of Mount Tucuche, the third tallest peak in TT at 3,071 feet. Ok, that’s not very impressive, but it’s still a nice hike:

And I was alone for all of them almost the entire time. I ran into a total of three other hikers, not counting the police special forces guys. TT’s hiking is awesome, super highly recommended.

The cities are, predictably, a lot less exciting. Outside the capital, it’s hard to even call them “cities.” TT unfortunately has that thing that a lot of developing countries have where minor population centers aren’t really built into coherent villages; rather, they’re just clusters of buildings constructed along major roads, so they all look the same and have no personality:

There is not a ton to see in Port of Spain either. Right beside a few impressive skyscrapers, there is a central square and market, both of which look pretty shabby. It’s always full of people liming (more on that later) and looking slightly suspicious. The markets themselves have the fun bustle of a bajillion people meandering around looking for god-knows-what. Right in the middle is Chinatown, which looks exactly like every other Chinatown on earth:

I like the weird modernist buildings clustered in downtown Port of Spain. Some are government, some are commercial, some are residential, but they are splattered around in a haphazard, ad hoc manner. I haven’t actually looked into this, but my sense is that most were built in the 1970s, because they all look like they could be in Logan’s Run or Rollerball or Soylent Green or any one of those funky 70s sci-fi movies:

The exception is the National Library, which has a wonderful classic look:

It would be a shame if someone were to attach a modernist monstrosity to it…

The main attraction of Port of Spain is the avenue. I mean, The Avenue, also known as Ariapita Avenue. It’s a road in a suburb on the outskirts of the city that contains dozens of restaurants, bars, and clubs. I’ve never found these sorts of things particularly interesting, but it’s a decent place to walk around and people watch, and, most importantly for TT and the Caribbean, a place to understand the phenomenon of…

Liming

I find liming kind of fascinating, not for what it is, but in a kind of abstract societal-implications sort of way. Liming is so simple that I found it a little hard to understand after Googling it. It had to be explained to me in person in Trinidad and Tobago.

Liming is the act of hanging out with other people and drinking alcohol. That’s it. That’s all it is. I’ve done it hundreds of times without knowing it.

What makes liming interesting is that it’s a really big deal in Caribbean cultures. In Notes on Guyana, I mentioned meeting a Guyanese woman on my flight to Guyana and asking what I should do there for fun. She hesitated and didn’t understand the question at first, but eventually told me to basically do liming. At the time, I thought she was being flippant, but now I think she was being earnest. Hanging out with people and drinking really is the primary social activity in places like Guyana and TT and seemingly all of the Caribbean.

After work, Caribbean people go liming. Before dinner, they go liming. At night, they go liming. When they should be getting home and going to bed, they go liming. At work, they often lime. They celebrate by liming. They mourn by liming. They lime before and after soccer matches. They lime for birthdays, for holidays, for festivals, for random days of the week. When they’re bored, they go liming. When they have responsibilities, they go liming.

Liming is arguably emblematic of a certain aspect of Caribbean culture – laziness. Or more charitably, a preference for leisure.

I am definitely not the first person to notice this. There is an anomalously high number of people sitting on street corners getting drunk in TT at all hours and in all places, from Port of Spain to rural towns in the mountains, from my 9 AM hikes to 2 AM returns from the bars. The chill beats of Bob Marley permeate the air at all hours of the day and night. The Trinidadian husband and wife business owners complained to me at length about constantly slacking employees who didn’t show up on time and couldn’t be trusted to work without supervision. I talked to a taxi driver with five kids who, with a jovial laugh, explained that he really should be working more, but he likes chilling with his friends too much. There’s “Island Time,” or “A notional system of time which others sometimes derogatorily ascribe to islanders (e.g. Hawaiians or Fijians), and which they sometimes jocularly ascribe to themselves, to account for their supposed tendency to be leisurely, not rigorous about scheduling, and often tardy.”

You can even hear it in the language. Being a former British colony, TT speaks English, but it’s Caribbean English. To my untrained ears, it sounds almost exactly like Jamaican English, though I’m sure they’d disagree. Most, but not all of the words are the same in TT English as standard American English, but the accent gives them a joviality with lots of rolling words and extra sounds. It feels less direct, more descriptive. I really had to focus to pick up on the meanings, and despite the well-earned reputation for Caribbean friendliness, I definitely annoyed some locals by asking them to repeatedly repeat themselves.

It’s hard to travel in the Caribbean and not get the sense that these are simply not people who place a great deal of value on industriousness. They like to talk, they like to drink, they like to celebrate, they like to party, they like liming.

To be clear, I’m not saying this is entirely a bad thing. The world works on trade-offs, not absolutes. The Caribbean work ethic is designed to create a relaxing lifestyle, one that is probably better suited to the heat and humidity of their environment. I’ve been told that they can see Americans and Europeans as uptight, stingy, neurotic, and sometimes rude. I’m guessing that like many Europeans, they see stereotypical Americans as needlessly work-obsessed and stressed.

Why is it called “liming?” The answer seems lost to history, but according to some amateur historians, the term originated in TT and may come from:

- Something to do with British soldiers stationed in TT and British people in general who are sometimes referred to as “limeys,” which is probably a reference to the British Navy adding limes to rations to prevent scurvy.

- A lime-based alcoholic punch made by local British soldiers that got people wasted.

- Farmers who would sit around and drink while waiting for lime to sink into their fields.

- Limestone miners who liked to get drunk.

And although it’s almost certainly false, another suggestion:

- Students at TT’s elite Queen’s Royal College who would skip class to day drink. When confronted by authorities, they would claim to be “limewashing,” or painting the bottom of trees with lime, a practice “done both for aesthetic appeal and as a form of protection for the trees.” Over time, “limewashing” became “liming” as a general slang term for hanging out and drinking.

Why Is It Trinidad AND Tobago? Because It’s Cheaper.

Trinidad and Tobago consists of two islands. As you can see from the map at the top, Trinidad is almost 16X larger than Tobago, and has almost 25X the population. Trinidad has the capital city, the seat of government, the tall buildings and essentially all the industry, but Tobago has the better beaches.

Why are these two islands one country?

For most of their histories, they weren’t united. Both were discovered by Christopher Columbus in 1498 on his third voyage, though he only stepped foot on Trinidad. Both were claimed as Spanish territories with nominal colonial administrations. Trinidad attracted minor settlement due to its location and the peacefulness of its Native population (who are nearly extinct now). It never became too economically valuable, but a slave-based plantation economy was developed around sugar and coca. Meanwhile, with its inferior agricultural land and hostile Natives, Tobago was left untouched besides a small coastal region. This developed into something of a colonial freedom haven by escaped slaves and pirates living entirely outside the enforcement of Spanish law.

In 1802, both Trinidad and Tobago were conquered by Britain as part of the Napoleonic Wars (in which the Spanish government was coerced into allegiance with France). By that point, Trinidad was a moderately profitable colony that looked like a lot of other Caribbean islands: a cash crop-based plantation economy, lots of slaves ruled over by a few Europeans, a few urban areas based around ports, and little industry. Tobago, which in 1791 had a population of 15,102 (only 541 of whom were white), was a full-fledged “pirate republic” which didn’t produce much but presumably consumed a lot.

The late 1800s saw the downfall of both economies and the Caribbean as a whole. For a good 200 years, islands like Trinidad, Jamaica, Cuba, Hispaniola, Curacao, and all those other little dots on the map had achieved something between decent and extraordinary profits based on plantation economies. At its peak, Haiti alone produced 60% of European coffee imports and 40% of sugar imports. Many contemporaries worried that the inevitable end of slavery would destroy the plantation system, but labor imports mostly from India lessened that blow. The ultimate cause of the plantation system’s downfall was global competition. By the late 1800s, sugar, tobacco, cocoa, dye, indigo, and coffee were grown throughout much of South America, Africa, and Asia, and usually at lower prices with even cheaper labor, and so the entire economic basis of the Caribbean went into decline.

European decolonization didn’t kick into gear until after WWII, but there were already top-down considerations of it by the late 1800s. Many Caribbean colonies simply weren’t profitable anymore. European governments were paying more in administration, legal, and military costs than they were getting in tax revenue. Britain, as the holder of the largest colonial empire in the world, began exploring cost-cutting options. A series of commissions were deployed to the colonies throughout the 19th century to consider administrative restructuring plans.

The colonial dream, which Britain would pursue in some form all the way into the mid-20th century, was to tie all of its Caribbean colonies into a single government. That would mean unifying the colonial administrations of Trinidad, Tobago, Barbados, Jamaica, the Bahamas, Grenada, Anguilla, the Cayman Islands, Honduras, Guyana, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent (and the Grenadines), and what was then called the British Leeward Islands, which itself was a political union forced on a bunch of British colonial islands in 1833 including Antigua, Barbuda, Montserrat, the British Virgin Islands, etc.

The point is, there were a lot of British colonial islands. Every one of them had their own local administrations, their own elites, their own middle classes, their own ex-slaves, their own unique ethnic make-ups, and their own often conflicting and contradictory political interests. The unification question inevitably brought up arguments about tax policy, tariff policy, where the capital would be located, etc. Smaller island colonies worried about losing political power while larger island colonies worried about paying higher tax bills.

Thus, British political attempts to wrap all of these entities into a union were predictably thwarted by intense (and usually elite-led) local resistance. Britain’s only leverage, aside from its overwhelming political and economic might, was that many of these colonies were rapidly going downhill as global cash crop prices continued to fall. While a grand unified British Caribbean colony would never be formed, Britain occasionally could force smaller unions.

Hence, in the 1880s, Britain was able to smash Trinidad and Tobago together. Trinidad was on the decline, but the catalyst was Tobago. In 1884, a major sugar company that dominated Tobago’s economy went bankrupt and the local colonial administration followed suit. The British government came in for a bailout but also imposed conditions, including a unified tariff policy with its larger neighbor. In 1889, Britain officially merged the colonial administrations of Trinidad and Tobago.

According to the Handbook, neither side was happy with the arrangement. Tobago was poorer, especially given recent economic conditions, and now Trinidad would have to stretch its finances a bit to cover new costs. Meanwhile, Tobago was granted a slightly privileged position in the meager colonial legislature, but its political power was almost entirely sublimated by Trinidad. Regardless, neither colony had the political will nor practical ability to defy its colonial master.

From 1958 to 1962, there was a preliminary unified British Caribbean country modeled after Canada and Australia called the West Indies Federation. It consisted of the modern nations of TT, Jamaica, Barbados, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Grenada, Dominica, and a bunch of other British territories that have remained British possessions to this day. The Federation was still technically a British colony but was primed for independence until it fell apart mostly due to Jamaica pulling out after being politically shortchanged and then TT following behind it.

By now, Trinidad and Tobago seem to have accepted their intertwined fates. Trinidad is still the economic and political center with the capital and all the important civil society stuff, but Tobago is prettier and gets all the tourists. To my knowledge, there is no current substantial effort to politically separate the two islands.

The Guyana Comparison

Haiti and the Dominican Republic are often used as good national data point comparisons. They are two small countries that occupy the same island, but one is a mid-tier developing nation and the other is one of the greatest political failures of the modern age. With geography as a near constant (though Haiti is hit worse by hurricanes), the differing policies, populations, cultures, and international relations of the two states can be compared to identify what causes a nation to succeed or fail.

I think TT and Guyana might actually be an even better comparison set than Haiti and the Dominican Republic. Obviously, TT and Guyana don’t have quite the same common geographic variable, though they are both based in the Caribbean. But TT and Guyana have remarkably similar political, economic, demographic, cultural, and social histories. Consider:

- Both nations are geographically and culturally Caribbean despite Guyana technically being part of South America.

- Both nations were initially claimed by Spain but ended up under British control due to the Napoleonic Wars. Both were granted independence by the British in the 1960s after a long series of negotiations between the British government and the democratically-elected local legislature.

- Both nations have small populations for sovereign nation-states (currently, TT = 1.5 million, Guyana = 830K).

- Both nations had Native populations that were wiped out by disease, slavery, and warfare. In both nations, the Natives have played a minor-to-nonexistent role in societal affairs since the 1700s. Today, there are very few Natives left.

- Both nations had colonial economies based on cash crop plantations (mostly sugar). In both cases, these economies went into decline in the late 19th century due to the abolition of slavery and a global decline in commodity prices.

- Both nations imported slave labor from Africa to work their plantations. In both nations, blacks became a majority of the population in the 1700s and vastly outnumbered their white masters.

- In both nations, slavery was outlawed by the British in 1834, resulting in a mass migration of blacks from rural areas to cities where they began claiming an increasingly dominant share of political and economic power.

- In response to the end of slavery and the loss of black slave labor, both nations opted to import cheap foreign labor. They both tried Portuguese and Chinese people, but found they weren’t suited for agrarian work and left the plantations as soon as their contracts expired. Both eventually settled for Indians via the British Empire, and both imported so many Indians that they became the co-dominant ethnic group in the nation along with blacks.

- In both nations, the Indian imports, unlike their black counterparts, held on to the culture and religion of their homelands. The notable exception being the caste system, which was mostly left behind (more so in Guyana than in TT).

- In both nations, there was a large degree of tension and sometimes outright political struggle between the blacks and Indians. There was/is fairly little social interaction between the two. Intermarriage was/is very rare, though blacks were generally more tolerant of it than Indians.

From the Handbook (written in the 1970s):

“In general, interethnic relations have been characterized by want of knowledge and lack of communication. Even though Trinidadians of all ethnic backgrounds may live near each other and occasionally attend each other’s festivals, such physical proximity has not engendered intermarriage or even interaction to any great degree. Stereotyping, diversity among cultural backgrounds, occupational segregation according to the ethnic group, and racial and religious endogamy have helped to preserve social distance and prejudice.”

This ethnic tension was sometimes explicitly exploited by the small white minority to maintain its declining political power:

“Competition and mutual suspicion between Negro and East Indian political movements have made it possible for foreign-oriented elites to play one group against the other, thereby preserving the emergence of political parties based on common socioeconomic interests.”

“White – particularly British – values and traditions are elevated, and Negro and East Indian modes are deprecated.”

- In both nations, racial groups had extremely similar stereotypes, with blacks being considered lazy, profligate, and promiscuous, while Indians were considered conservative, hardworking, clannish, and nepotistic. The small Chinese minority was praised for its honesty and business acumen. I’ll spare us from many of the more colorful descriptions of blacks and Indians from the 1970s-era handbook, but this description of the Chinese is fun:

“[They] tended to ignore island politics and organized themselves into various semisecret societies.”

- In both nations, the family structures of the racial groups followed similar trends.

Black family structures were influenced by the cultural legacy of slavery. Hence, they had low rates of marriage, high rates of child illegitimacy, high rates of infidelity, and woman-led households. It was common for men and women to date and live together and even have children without marriage (known as a “visiting union”) until the man decided to move on and “invariably” leave the child with the mother. A survey in the 1970s found that 2/3rds of young black TT women had illegitimate children. From the Handbook:

“Creoles, on the other hand, stress monogamy, legal marriage, and the nuclear family as the ideal approaching contemporary Europe, but only a small percentage – those in the middle and upper classes – even approximate this ideal.”

Indians had the opposite in all regards with extremely tight family structures to the point of insularity. Arranged marriages were the norm, but Indian women had veto power over their parents’ choices. The same 1970s survey found that 10% of TT Indian women had illegitimate children. From the Handbook:

“East Indians, on the other hand, retain the ideal of the patrilineal extended family. Although it has been altered and eroded by the increasing independence of children and women, it retains its essential flavor and characterizes most social intercourse.”

- By the early 20th century, the populations of both nations were almost evenly split between blacks and Indians, with blacks dominating the cities and Indians dominating the countryside. In both nations, blacks were more politically conscious and active, while Indians were increasingly more economically successful. In both nations, a small white and Chinese minority held extremely outsized economic power but rapidly diminishing political power.

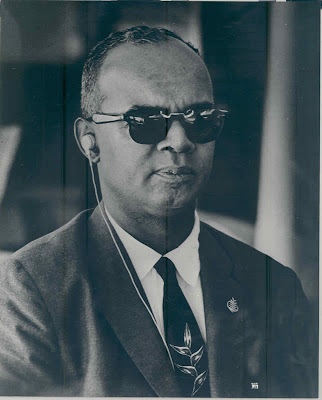

- Shortly before independence, in both nations, the black polity unified behind a political party and a popular leader who was elected to power. This party and individual retained control of the nation during independence and into the 1980s when he died due to a throat-based ailment. He was succeeded by a less charismatic but more liberal lieutenant who only held on to power for another five-ish years until the dominant black party finally lost power.

- In both nations, in the early to mid-1990s, an Indian leader and political party succeeded a black leader and political party for the first time in the nation’s independence. This party has stayed in power (with brief interruptions and more than one constitutional crisis) until the current day.

- Both nations have/had a ton of oil and that has had huge implications on their political/economic progression.

With all of these historical similarities, why is TT so much better off than Guyana along the usual metrics: wealth, political stability, etc.?

According to the analogy, TT is to the Dominican Republic what Guyana is to Haiti. Both TT and the DR are middling developing nations with corrupt leadership, flawed but basically functional democratic institutions, OKish economic growth, extremely high crime rates, and a sizeable tourism industry. And that makes Guyana the Haiti analog with both nations being among the poorest and least functional in the Western Hemisphere, though Haiti is notably worse off.

I need to throw up a big caveat in these comparisons: oil. Guyana revealed its oil discoveries in 2015 and began profiting from them in 2020. Since then, it has established the largest per capita oil reserves on earth and has achieved stratospheric double-digit GDP growth annually, putting its per capita GDP PPP levels among the highest nations on earth.

That’s obviously a huge variable that throws any national comparison out the window. So for the sake of this section, imagine the clock has been wound back to 2015. TT’s GDP per capita was $18,500 compared to Guyana’s $5,700. Guyana is still an absolute basket case and economic failure.

From this standpoint, what did TT do right and/or Guyana do wrong? Or was it a matter of luck and external factors? Here are some considerations:

TT Has Oil and Gas

While Guyana didn’t strike its oil until 2015, oil and gas has been a part of TT’s entire modern history. All the way back in 1595, Sir Walter Raleigh spotted Trinidad’s Pitch Lake, a coastal petroleum deposit sort of like Los Angeles’s La Brea Tar Pits. In 1865, an American set up Trinidad’s first oil company. In 1910, the British Navy controversially converted from coal to oil, and the British government looked across its vast empire for potential oil suppliers. Trinidad was quickly identified and not only was oil production rapidly expanded, but its first oil refineries were built at such scale that Trinidad began importing crude oil. By 1938, oil amounted to 70% of export value, though it only employed 13,000 people. By 1959, the oil industry employed only 20,000. By 1965, oil revenues were 80% of export value. In 2022, the oil and gas sector accounted for 29.8 percent of GDP and 81 percent of export earnings.

Maybe there is no need for any other historical investigation. Maybe the difference in the prosperity between TT and Guyana can be determined by the simple fact that TT has had oil and gas for over a century and has made a small fortune off of it.

I think this is definitely a significant component but doesn’t tell the whole story.

As I wrote about back in Notes on Saudi Arabia and Notes on Nigeria, many countries throughout the world have been blessed with abundant oil reserves yet so few have managed to tap into them without inviting rampant corruption, incompetence, and factionalism. Miles from TT’s shores, Venezuela has the largest oil reserves on earth, and after decades of prosperity, the government managed to run the entire venture into the ground and create one of the few truly failed states of the Western hemisphere.

As with Saudi Arabia, the question to ask is how did TT’s government manage its oil wealth so well? Or at least relatively well compared to most other oil-rich states? How did it use the oil wealth to finance a reasonably wealthy and stable developing economy instead of becoming a crooked petrol state or imploding in on itself?

British Colonial Oversight

I think the British deserve a lot of credit. Many, though by no means all of the initial pitfalls of typical oil economies were avoided in TT because of British oversight. The British government financed TT’s oil extraction and the immediate jump to refinement (which is a tremendous value-add). The British set up the managerial infrastructure for running the oil operations and facilitated their transition to local ownership after independence. Thus, there wasn’t the typical rampant corruption and tribalistic battles for resource control which tend to plague oil economies like Nigeria or Angola.

Granted, the British oil management was not conducted altruistically. The British oil interests were owned by Brits, paid low royalties locally, and given the nature of the industry, employed few locals. But British oil operations were turned over to TT’s government in the 1960s, so in a sense, the British did for TT what the US oil companies did for Saudi Arabia. In both cases, foreigners built the infrastructure and ran the companies for 50+ years and then the locals took over a solid base of operations. Compare TT and Saudi Arabia to the likes of Iran and Venezuela where foreign-built oil complexes were coercively nationalized and subsequently run into the ground.

It was (selfish, imperialistic, imperfect) British oversight that brought TT’s economy to fruition, and a good indicator of this trend has been the post-British state of TT’s oil and gas industry. While it has been nowhere near a Venezuela-tier disaster, it definitely hasn’t been as well run as Saudi Arabia where Aramco continues to be one of the most profitable companies on earth. Trinidad’s oil and gas companies are corrupt, scandal-ridden, embezzlement-ridden, and have been periodically broken apart and restructured by reformists. For instance, the now-defunct Petrotrin:

“became the embodiment of poor corporate governance, expressed in bad policy decisions, wastage, corruption and nepotism across governments. The power of the Oilfields Workers’ Trade Union over the company due to consolidation of past state oil companies made it even more difficult for management to institute changes. On 28 August 2018, it was announced by Prime Minister Dr Keith Rowley that Petrotrin would have to be shut down (although earlier stating in his political campaign they would not shut down the state-owned company) because of the government and company’s inability to generate a profit during a period of low oil prices, where TT$8 billion was lost over five years. Also cited by the government was lack of competitiveness, declining production, TT$12 billion in debt, and the loss of foreign exchange due to the importation of oil to be used together with locally produced oil to keep the refinery in operation. According to the government, a cash injection of TT$25 billion would be required to refresh its infrastructure and repay its debt. On 30 November 2018, Petrotrin was shut down with the country’s largest refinery officially closed after 101 years in operation. Approximately 5,500 permanent and temporary/casual employees lost their jobs.”

But again, it’s all relative. TT’s British-facilitated corrupt and inefficient oil and gas industry is still productive enough to constitute almost 1/3rd of the economy and provide a higher standard of living than almost anywhere else in the Caribbean.

Leadership and the Ethnic Power Balance

Guyana and TT faced the same (extremely specific) economic-demographic conundrum. In both countries, the population was roughly equally split between blacks and Indians. In both countries, the black population had better political organization but the Indian population was increasingly more economically productive. This exacerbated a long-standing mutual resentment between the two groups and provoked fears that either the Indians would use their wealth to marginalize the black population, or the black population would use political power to marginalize the Indian population.

The Guyanese solution was black dominance and Indian repression. Forbes Burnham, with support from the CIA and the British government, led his black party to power with a fraudulent election and then cemented his leadership with political violence, spoils, and corruption. From Guyana’s independence in 1966, Burnham spent almost 20 years building a regime to systematically marginalize the Indian population. Indians were removed from administrative posts, civil service jobs were given almost exclusively to blacks, Indian businesses and industries faced higher taxes and more onerous regulations, and black businesses were given virtually all government contracts. At its most extreme, the regime turned a blind eye to black gang and paramilitary violence against Indians. At the top of it all, Burnham himself was boorish, despotic, and dictatorial, and his heavy-handed leadership was seen as a form of additional humiliation to marginalized Indians.

With Burnham’s death in 1985, his black-dominated political party retained power for a few more years before finally losing to the Indian party in the early 1990s. What has followed to this day has been a sort of low-tier simmering racial struggle that occasionally bubbles up into violence. The Indians have mostly maintained power, but, according to many, they have enacted a more subtle version of Burnham’s repression by systematically excluding blacks from civil service jobs and government contracts while setting up profitable Indian corruption networks. Almost 60 years since Guyana’s independence, there remains the sense that its two most prominent ethnic groups are in an eternal struggle for control of the government, the economy, and society at large.

Again, the TT’s contrasting policies in this domain have by no means been perfect, or even particularly good, but they seem to have been way less bad, or at least more competently managed.

Guyana’s pre-colonial history was a two-man battle between Burnham and his Indian rival Cheddi Jagan, but TT’s colonial ascension was a one-man show. Eric Williams was born in 1911 to a middle-class family with a mixture of black and French ancestry (which made him “colored” at the time). Like Burnham, Williams was educated abroad in Britain, but unlike the thuggish Burnham who quickly returned home to get into union politics, Williams was a genuine intellectual and made a career out of it for a good 20 years. In addition to his early autobiography (awesomely) named Inward Hunger, Williams turned his Ph.D. thesis into a book, Capitalism and Slavery, which is apparently one of the most influential history books ever written on the British slave trade.

The Handbook describes Williams as having “ambition, determination, and capacity for long and concentrated work” with a serious, “dry and pedagogic manner.” During his time in Europe, he developed a sense of racial resentment against white people for the perceived or real sleights perpetrated against him in academia. He wasn’t particularly charismatic or naturally suited to politics, but he was smart and highly organized, and like Burnham and Jagan, he got into Caribbean politics during the build-up to independence which seemed to be the perfect time for ambitious individuals to rapidly rise to power.

In 1944, Williams was put on the Anglo-American Caribbean Commission, one of the British committees sent to its Caribbean colonies to figure out how to structure inevitable independence. A few years later, he settled down in Trinidad and became an academic who gave extremely popular public lectures on “world history, Greek democracy and philosophy, the history of slavery, and the history of the Caribbean.”

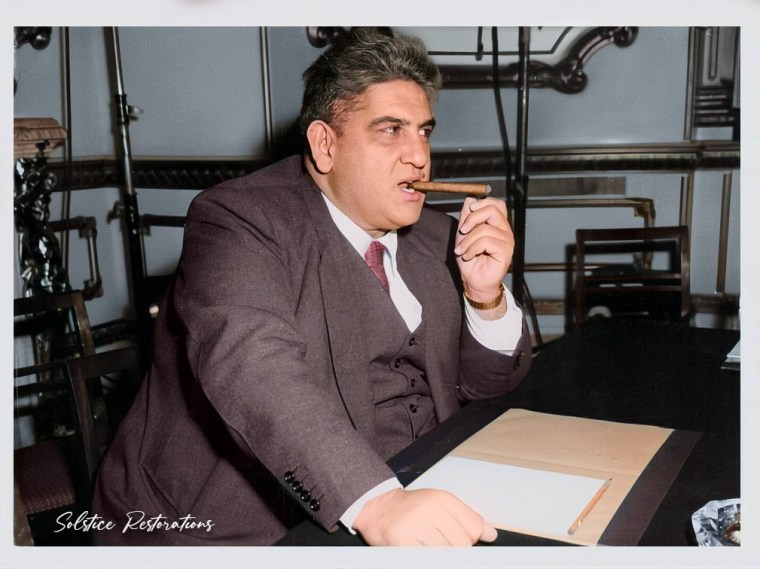

In 1956, Williams formed his own political party, the People’s National Movement (PNM). It stood against the Indian-based People’s Democratic Party (PDP) and the dominant moderate party led by Albert Maria Gomes, a very interesting fellow in his own right. Gomes was an extremely popular ethnically Portuguese journalist who slid into power by being the compromise candidate for all sides – neither black nor Indian, neither a radical nationalist nor a British lackey – yet he still skillfully laid the groundwork for independence and lessened British economic interference in the economy. Also, he looked like a caricature of a fat gangster:

Like Williams, his PNM party was leftist and nationalistic, but not radical. It established its initial base in black intellectuals who found Williams through his lectures but then built out to the wider black majority with the exception of hardcore Catholics and wealthier blacks who stayed with the moderate party. In 1956, its first year of operation, the PNM won a majority of seats in the colonial legislature. After some hiccups and reshuffling as Williams developed his political skills, the PNM won again in 1961. The following year, Williams’ government negotiated the final terms of independence and Trinidad and Tobago became its own nation. Williams then ruled as TT’s first Prime Minister until his unexpected death at age 69 in 1981.

I like this description from the Handbook on ethnic relations under Williams:

“Rather than adopt or adapt, Trinidadians have learned to tolerate existing differences and have developed an attitude that one social scientist characterized as ‘negative indifference.’ Negative indifference is tolerance without positive acceptance of the intrinsic validity of the beliefs and life-style of the other group.”

It’s not ideal, but it’s certainly better than the alternative found in Guyana. While Burnham’s regime systematically suppressed Indian political organization and economic progress, Williams took a moderate approach. Political power was consolidated under the PNM and blacks got most government positions, but the key point of compromise was to maintain neutrality on the economic front. Indian industries (mostly agriculture) did not face discrimination or unfair laws. Indian businesses were not excluded from government contracts. Indian migration to the cities moderately accelerated and Indians gained an increasing share of the middle class. Essentially, Williams orchestrated a system where black Trinidadians had more political power but Indian Trinidadians had increasingly more economic power. From the Handbook:

“Africans perceived the PNM as providing many economic concessions to South Asian businessmen, for example in the construction, insurance, financial, manufacturing and commercial sectors of the economy.”

“The fact is that, during the PNM era, Africans were in political control, and South Asians were economically prosperous and politically relevant.”

“Expectedly, the economic success of South Asians breeds significant feelings of resentment among the Africans. The economic success of South Asians tends to increase the determination of Africans not to allow the former to have dominant political control. Political power is seen by Africans as a tool that enables them to counterbalance the economic prominence of the South Asians. Without political power, Africans think that their position in the society will be very dismal, since South Asians who are now economically prominent will also control political power.”

To accomplish this, Williams made small but crucial cross-racial political alliances. In Guyana, the vast majority of Indians backed Jagan’s Indian party and the vast majority of blacks backed Burnham’s black party, but in TT, Williams’ PNM always had support from the majority of Muslim Indians who tended to feel excluded from the Hindu majority. Likewise, many wealthier city-based Indians supported the PNM due to the Indian PDP’s preference for Indian-dominated rural industries.

From reading about all this, I get the sense that a key factor at play was the sheer intensity of political and ethnic divisions. Guyana and TT basically had the same issues: a racially divided nation was launching a democratic government, so the two major ethnic groups were using politics to achieve dominance. But the intensity of the division in Guyana was so extreme that it resulted in rioting, gang warfare, blowing up buildings, assassinations, and eventually systematic political oppression. TT simply never got that crazy. It had plenty of protests and some rioting, but the two sides were never at each other’s throats, not even when the Black Power Movement swept through the country and a substantial portion of the black vote was angling for a Burnham-ish political regime.

Why were TT’s politics so much less intense? I have four theories:

- The ethnic demographic population balance was slightly different in an interesting way. In Guyana, the Indians were a slight majority while in TT the blacks were a slightly larger majority. In both countries, black political organization and consciousness was significantly more advanced. In TT, this let the black PNM achieve power with relative ease. In Guyana, the better black political organization was matched by the larger Indian population, and thus you had a closer political fight which rapidly heated up and became violent. In other words, TT had a more easily attainable political steady-state where a strong black party could achieve hegemony; Guyana had a multi-polar system with no easily dominant faction, and without a mature democratic system, the competition between the two factions resulted in factional war.

- TT never had an Indian leader as skilled and charismatic as Guyana’s Cheddi Jagan. He single-handedly pushed Indian political organization and consciousness forward by decades and made the Indian party competitive with the black party. TT never had a strong Indian opposition until the 1980s. Without Jagan, Guyana’s Indian party probably would have lost more peacefully to Burnham’s black party and the subsequent Burnham regime wouldn’t have been as suppressive.

- Williams was a better, more competent, and more moderate leader than Burnham. By the time TT got its independence, Williams and the PNM probably had the political capital to launch a PNM-type regime, but Williams lacked the personal viciousness and incentive to do so.

- The CIA and the British government interfered in Guyana’s pre-independence elections to put Burnham in power while TT was spared any such interference. This probably had a lot of destabilizing influence in Guyana by empowering the thuggish Burnham and undermining democratic norms.

Some Observations on TT’s Slavery

According to the Handbook, Trinidad and Tobago’s white masters treated their slaves famously well, at least by the extraordinarily low standards of Caribbean slavery. Yes, it feels weird to talk about treating slaves “well,” but even hell has many levels. For instance, Guyanese masters infamously treated their slaves terribly and had much higher run-away rates and slave revolts (though the causal direction is unclear).

In 1823, the British Empire instituted a bunch of new laws to improve slave treatment, including:

- Outlawing the flogging of female slaves

- Automatic freedom for female slaves born after 1823

- Slaves get off from work on Sundays

- Regulations for slaves to buy their own freedoms

- Slaves could provide testimony against their masters in court

Guyana ignored the new rules because the masters believed they needed to be brutal to stop their slaves from fleeing to the jungles where they would never be recaptured. Meanwhile, TT had already implemented pretty much all the new rules by local laws or informal customs.

Perhaps related, TT slaves had unusually high value. In 1837, when Britain ended slavery, it provided financial compensation to all slave owners. TT slaves were valued at an average of 56 pounds, compared to 25 pounds in Barbados and 23 pounds in Jamaica.

(Note – I’m taking these numbers from the Handbook but I’m not sure how they line up with slave prices in the US, which I’ve seen at an average of $400-1,000. Also, from Wikipedia, the Slave Compensation Act spent 20 million pounds on 40,000 slaves, or 500 pounds per slave. I don’t know.)

Emancipation was also much smoother in TT than most of the Caribbean. Once it became official, many TT slaves immediately left their plantations and flooded into the cities even though it was against the law. Officially, slaves were legally obligated to keep working for their masters (for pay) for seven years as part of an “apprenticeship” program, so the ones who immediately left their plantations were technically outlaws. But rather than crack down, the British Governor of TT let it go and even facilitated the purchase of small, cheap land plots for ex-slaves. After four years, the Governor officially ended the apprenticeship program prematurely.

Also, when slavery was ended, TT’s plantation owners searched for a new source of labor and eventually settled on importing Indians. But before the Indians and even before the experiments with the Portuguese and Chinese, they tried to get free American blacks to move to TT. The logic was that they already had a large black population so they were culturally compatible, and TT was willing to provide cheap land and relative political freedom that would be unavailable in the United States, especially in the Antebellum South. Only a few thousand American blacks ended up moving to TT, but it was an interesting idea.

The Islamic Coup

One more historical digression – in 1990, Trinidad and Tobago faced a radical Islamic coup.

There were always a bunch of Islamic missionaries in TT who tapped into the Black Power movement to get converts. A group of particularly radical converts founded Jamaat al Muslimeen in 1982 as a community organizing group that did missionary work, provided food and health care to the poor, and later formed anti-drug vigilante squads. Eventually, the group may-or-may-not have become something of a gang, or at least it appeared to be hoarding weapons, and they faced increased attention from the police, including numerous arrests of its leader.

In July 1990, Jamaat al Muslimeen tried to seize control of the government of Trinidad and Tobago. They started by firebombing a police station and then 42 armed men stormed the Parliament (the Red House) and took much of the government hostage, including the prime minister, who was beaten and then shot in the leg when he called for military reinforcements. Dozens of other militants attacked the country’s one television station and two radio stations. Within 30 minutes of all attacks, the group’s leader went on tv to declare that the government had been overthrown and he was negotiating with the military to set up a new government.

This was a bit of an exaggeration. Instead, the military repulsed Jamaat al Muslimeen’s forces from the radio stations and retook the television station while the Red House was put under siege. What remained of the civilian government set up an outpost in the nearby Hilton Hotel. For six days, the coupers and the government negotiated until they settled upon a surrender in exchange for amnesty. The militants laid down their arms, walked outside, were arrested and subsequently released.

Jamaat al Muslimeen may not have succeeded in its goal of taking over the government of Trinidad and Tobago, but considering they seized Parliament, killed 24 people (including one Member of Parliament), shot the Prime Minister, and caused millions of dollars in property damage, but never faced jail time or any criminal penalties, I’d say their effort was more successful than the average coup attempt.

Driving

Transportation in Trinidad and Tobago is weirdly awful. The bus system is impossibly confusing for a country with relatively few roads. There is one bus that goes from the main airport to the capital’s center, but it seems to only come a few times per day. There are shared ride vans in Port of Spain, but relatively few and their routes are confusing. Uber and Lyft don’t exist. Most bafflingly of all, there are no normal taxis driving around TT, not even in Port of Spain. If you want a taxi, you have to order one in advance, and they take forever to arrive.

So I opted to rent a car. I’ve done so in Mexico, Panama, Saudi Arabia, and Suriname, and it has become one of my go-to travel recommendations if you have the time and money. It’s one of the best ways to get a feel for a country, to understand its flow, to know its countryside, to get to little nooks and crannies and sites that are difficult or impossible to reach by bus.

My driving experience in TT was positive on net because it got me to all those remote hiking spots, but it was also a nightmare. I don’t think I’ve done more stressful driving in my life. This was partially my fault and partially TT’s fault.

The part that was my fault is that I’m not used to driving on the wrong left side of the road. I had done so once before in Suriname and didn’t find it difficult. Once you get used to the idea of entering roundabouts on the opposite side and right-turns being the tough ones, it’s fine, it feels like normal driving.

But once I got in my car in TT, I realized that the hard part wasn’t driving on the left side of the road, it was sitting in the right side of the car. For whatever reason, my car in Suriname had its wheel on the left side, but I had no such luck in TT. I got into the car in a narrow back alley in the middle of Port of Spain, and while trying to psyche myself up to pull out into a major throughway, I realized that I had never developed the proprioception to intuitively feel how far a car extends to my left.

Less than ten minutes later, I took a right turn and scraped a parked car.

It was a minor accident, but the first car-on-car collision of my life. I wasn’t even 100% sure that I had hit something; I hoped the violent scraping I had heard was just a sound my shitty 20+ year old rust bucket rental made sometimes. Still, I drove 20 feet ahead looking for a place to pull over when a guy yelled at me and banged on my car. I found a parking spot, got out, he yelled at me some more, I apologized, and then he calmed down. I checked out my car first, and saw a very minor indent and some scraped paint. Then I checked his car, which was even older and shitter than mine, and saw another slight indent with some scraped paint.

After some more back-and-forth, he said, “hey man, we can go down to the police station and report this, or we can handle this here.”

That sounded good to me, but I had no idea how to price this, so I asked him what was fair. He hesitated, looked me over, and then weakly suggested 500 TT dollars, which is about $73. That actually didn’t sound too high to me, but based on how he said it, he was obviously fishing. I countered 200 TT dollars ($30) and he immediately agreed. I was probably slightly ripped off, but whatever. I gave him the money, he gave me a fist bump, and I drove off.

For the next three days, I drove around Trinidad without listening to music or podcasts. My eyes were glued to the road or my mirrors. I became a hyper-vigilant model driver, and successfully so with no further crashes.

It was my fault that I was bad at driving on the left side of the road from the right side of the car, but it was TT’s fault that the roads and drivers suck. The quality of the main roads is pretty good, especially compared to other Caribbean countries, but they are so fucking narrow. Everything but the highways is tight, and once you get out of Port of Spain, it’s brutal. Every approaching car becomes a Tetris challenge of moving to the side of the road and trying not to die. I’m honestly a little surprised I didn’t scrape any more cars in the smaller cities.

The worst is the mountains. Their roads have actually given me a greater appreciation for the engineering skill required to build decent roads in mountains everywhere else in the world. Normally I don’t think about stuff like, “how far should the road go before a switchback” or “what is the max incline/decline degree for practical driving,” but TT’s mountain roads look like something that I would make in a Sim City type game where I’m connecting my city to a distant mine and I don’t give a fuck and have no clue what I’m doing.

As for the drivers, I can’t tell if they are amazing at driving or terrible. They’re terrible in the sense that they drive way too close to me, way too fast, and make me nervous. They are amazing in the sense that, in stark contrast to me, they have a supernatural sense of vehicular proprioception, and can seemingly squeeze their cars of any size through any gap or down any pathway. Then again, maybe 20% of the cars had dings and dents, so they probably mostly suck at driving.

Cockroach Cave

How does one measure bravery?

Some measure it by the choice to embark on risky endeavors. I have been called brave for going to countries that are dangerous due to their crime, corruption, or political conflicts. In all honesty, I generally disagree, and find that as long as an individual is cautious and a basically competent traveller, it is not actually risky to travel to even most notoriously dangerous countries. I deserve little bravery credit for my travels.

Perhaps bravery should be measured not by the objective riskiness of an action, but by an individual’s ability to undertake an action despite his fear of it. By this standard, I have direct evidence that I am a coward.

In Trinidad, there is this cave in the mountains that’s filled with cockroaches. I can’t find it on Google and I can’t login to my AllTrails account anymore, but I swear it’s out there. If anyone knows where I’m talking about, let me know in the comments.

All the descriptions said that it’s literally just a cave filled with cockroaches. It was on the way to one of my hiking trails, so I found it on my map, parked on the side of the road, and saw it:

Then I saw this on the ground:

And I couldn’t. I just can’t. I fucking hate cockroaches. There’s something about them. I could tolerate the cave being filled with snakes or spiders, but I can’t do cockroaches. I turned around and left.

I found this video online, and I’m not sure if it’s the exact same Trinidadian cave, but it’s close enough. Either way, I’m glad I didn’t go in.

Miscellaneous

- Another similarity between TT and Guyana – they were both suspected locations of El Dorado, the City of Gold. In the late 1500s and early 1600s, Sir Walter Raleigh made two trips to Trinidad to find the city. He was unsuccessful.

- Also like Guyana though not to the same degree, Trinidad and Tobago is weirdly fairly expensive, especially its housing. I couldn’t find a place to stay in Port of Spain for less than $70 per night, partially because there are no hostels. Outside the capital, it took me quite a bit of searching to find a $25 per night hotel, but given that it also had options to pay by the hour, it was not the most reputable establishment. Still had Netflix though.

- These days, TT is actually more of a natural gas economy than an oil economy , with the 41st largest oil reserves and the 36th largest natural gas reserves. Though based on proven reserves and current consumption levels, TT only has 14 years of natural gas left.

- Some sources, including two locals I met, claim TT has the world’s largest roundabout surrounding Queen’s Savannah Park in Port of Spain. But, the thing about roundabouts is that when they get big enough, they just become big circular roads and, IMO, it becomes difficult to consider them roundabouts. Plus, Malaysia seems to have a bigger one.

- Flashbacks to Notes on Benin: