$\begingroup$

This question is motivated by teaching : I would like to see a completely elementary proof showing for example that for all natural integers $k$ we have eventually $2^n>n^k$.

All proofs I know rely somehow on properties of the logarithm. (I have nothing against logarithms but some students loathe them.)

Is there a brilliant "proof from the book" for this inequality (for example given by an explicit easy injection of a set containing $n^k$ elements into, say, the set of subsets of $\lbrace 1,\ldots,n\rbrace$ for $n$ sufficiently large)?

A fairly easy but somewhat computational proof (which leaves me therefore unhappy):

Given $k$ choose $n_0>2^{k+1}$. For $n>n_0$ we have \begin{align*} &\frac{(n+1)^k}{2^{n+1}}\\ &=\frac{1}{2}\left(\frac{n^k}{2^n}+\frac{\sum_{j=0}^{k-1}{k\choose j}n^j}{2^n}\right)\\ &\leq \frac{n^k}{2^n}\left(\frac{1}{2}+\frac{2^k}{2n_0}\right)\\ \leq \frac{3}{4}\frac{n^k}{2^n} \end{align*} showing that the ratio $\frac{n^k}{2^n}$ decays exponentially fast for $n>n_0$.

A perhaps more elementary but slightly sloppy proof is the observation that digits of $n\longmapsto 2^{2^n}$ (roughly) double when increasing $n$ by $1$ whilst digits of $n\longmapsto (2^n)^k$ form (roughly) an arithmetic progression. (And this "proof" uses therefore properties of the logarithm in disguise.)

Addendum: Fedor Petrov's proof can be slightly rewritten as $$2^{n+k}=\sum_j{n+k\choose j}>{n+k\choose k+1}>n^k\frac{n}{(k+1)!}$$ showing $$2^n>n^k\frac{n}{2^k(k+1)!}>n^k$$ for $n>2^k(k+1)!$.

Second addendum: Here is sort of an "injective" proof: $n^{k+1}$ is the number of sequences $(a_1,a_2,\ldots,a_{k+1})\in \lbrace 1,2,\ldots,n\rbrace^{k+1}$. Writing down the corresponding binary expressions, adding leading zeroes in order to make them of equal length $l\leq n$ (with $l$ such that $n<2^l$) and concatenating them we get a binary representation of an integer $<2^{l(k+1)}\leq 2^{n(k+1)}$ which encodes $(a_1,\ldots,a_{k+1})$ uniquely. This shows $$2^{(k+1)n}>n^{k+1}.$$ Replacing $(k+1)n$ by $N$ we get $$2^N>N^k\frac{N}{(k+1)^{k+1}}>N^k$$ for $N$ in $(k+1)\mathbb N$ such that $N>(k+1)^{k+1}$.

For the general case we have $$2^{N-a}>N^k\frac{N}{2^a(k+1)^{k+1}}>(N-a)^k\frac{N-a}{2^a(k+1)^{k+1}}>(N-a)^k$$ (where $a$ is in $\lbrace 0,1,\ldots,k\rbrace$) if $N-a>2^k(k+1)^{k+1}$.

Variation for the last proof: One can replace binary representations by characteristic functions: $a_i$ is encoded by the $a_i$-th basis vector of $\mathbb R^n$. Concatenating coefficients of these $k+1$ basis vectors we get a subset (consisting of $k+1$ elements) of $\lbrace 1,\ldots,(k+1)n\rbrace$.

$\endgroup$

19

$\begingroup$

Assume that $n>k$. Then $$2^n=\sum_{j=0}^n {n\choose j}>{n\choose k+1}=n^k\left(\frac{n}{(k+1)!}+O(1)\right).$$

$\endgroup$

19

$\begingroup$

For $n>k+1$, substitute $2n$ for $n$ in both $2^n$ and $n^k$. Note that the first is multiplied by $2^n$ and the second by $2^k$ which is at least twice as small. Therefore applying this enough times will make $2^n$ larger than $n^k$, since both are larger than $0$.

$\endgroup$

16

$\begingroup$

The cleanest way I can think of is to show that if $p(n)$ is any polynomial with integer coefficients, then eventually $p(n)<2^n$ for large enough $n$.

Proof

The proof is by induction - the degree zero case hopefully being obvious.

Suppose the result holds for degree smaller than $k$, and $p(n)$ has degree $k$.

Then $p(n+1)-p(n)$ has degree strictly less than $k$ (one doesn't even need to get into the full binomial expansion to convince a student of this, just observe that $(n+1)^k=n^k+\dots$, where the remaining terms have degree smaller than $k$.)

Therefore, eventually

$$p(n+1)-p(n)<2^n = 2^{n+1}-2^n,$$ or equivalently, $$2^n-p(n) < 2^{n+1}- p(n+1).$$

Thus $2^n-p(n)$ is eventually strictly increasing, and hence (as an integral sequence) will eventually become and remain positive, and so the case for degree $k$ is proved.

$\endgroup$

1

$\begingroup$

I think this is an explanation good for a variety of levels. This is in some of the other answers but I'd emphasize that writing it out with discussion at each point can be more clear than some of the computation.

Think of the ratio between consecutive terms in $n^k$: $\left(\frac{n+1}{n}\right)^k$.

And compare $$n^k = \left(\frac{2}{1}\right)^k \left(\frac{3}{2}\right)^k \cdots \left(\frac{n}{n-1}\right)^k $$ $$2^n = \underbrace{2 \cdot 2 \cdots 2}_{\text{n times}} $$

I think here some students can already imagine the rest of an explanation.

Now, you need to explain that we can find $n_0$ such that $\left(\frac{n}{n-1}\right)^k < 1.5$. (Of course easiest by taking logs :) but I think this is more intuitive than the original fact.)

And then you need to explain that we can write

$$n^k = \left(\frac{2}{1}\right)^k \left(\frac{3}{2}\right)^k \cdots \left(\frac{n_0}{n_0-1}\right)^k \left(\frac{n_0+1}{n_0}\right)^k \cdots \left(\frac{n}{n-1}\right)^k $$ $$n^k \leq \underbrace{\left(\frac{2}{1}\right)^k \left(\frac{3}{2}\right)^k \cdots \left(\frac{n_0}{n_0-1}\right)^k}_{\text{some constant}} \underbrace{\frac{3}{2} \cdots \frac32}_{n-n_0 \text{ times}} $$

And it comes down to explaining that, if $a > b$ then $C_1 a^n$ eventually beats $C_2 b^n$.

On a board or with some pictures, you can get a lot out of writing the results out in the "$\cdots$" form, since you can put a big square around the terms that we stuff into the "constant" and emphasize that we don't care how big we got up to that point. I like this explanation because I think it's quite open to discussion as you go, and invites some thought from advanced students; like, how does the choice of $3/2$ affect things like the final estimates we get? We're ultimately bounding polynomial growth from above by exponential growth!

$\endgroup$

$\begingroup$

The following proof works for any real $k>0$ (the case $k\le0$ is obvious).

For $a:=2^{1/(2k)}-1>0$, we have

$$\frac{2^n}{n^k}=\Big(\frac{(1+a)^n}{n^{1/2}}\Big)^{2k}

\ge\Big(\frac{1+na}{n^{1/2}}\Big)^{2k}

\ge(an^{1/2})^{2k}\to\infty$$

as $n\to\infty$.

$\endgroup$

$\begingroup$

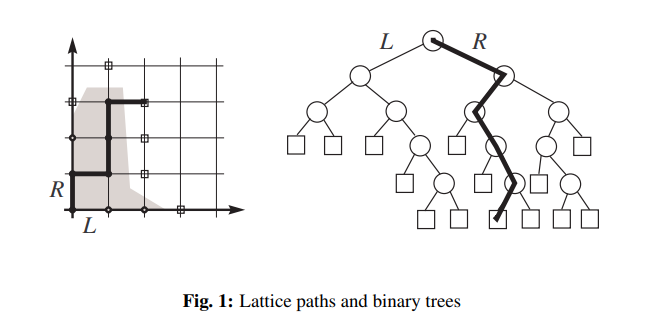

A more visual perspective (not sure about proof) is embedding a tree formed by $n^{k}$ into the binary-tree formed by $2^{n}$.

For $k=1$, we have the following picture

(from "Average Redundancy for Known Sources: Ubiquitous Trees in Source Coding")

(from "Average Redundancy for Known Sources: Ubiquitous Trees in Source Coding")

Along each diagonal in $Z^{2}_{+}$, we have linear growth 2,3,4,5. Whereas for the binary tree we have 2,4,8,16. So the lattice path has more options in the binary tree.

We see that in $Z^{2}_{+}$, every interior vertex has two-parents eg. (1,1) has parents (1,0) and (0,1). Whereas in the binary-tree every parent has two children vertices.

Every lattice upright path in $Z^{2}_{+}$ has a unique corresponding descending path in the binary-tree. We have a bijection. The number of paths that reach the node $(n,n)$ is exactly $2n$ (we just need more than one). Whereas for the binary tree every node can only be reached by exactly one path. Therefore, we must have fewer nodes on the diagonal connecting $(n,0)$ and $(0,n)$, then we have at the $n$-th level in the binary tree.

You could also ask "Suppose we have two cities A and B, in A every parent can single-produce two children and in B every children must have two parents, which population will grow faster?" i.e. $2^{n}\geq 2n$ for $n\geq 1$.

For higher $k$

I think for polynomial $n^k$, we might be able to take $\mathbb{Z}_{+}^{2k}$ (check), because each time we take another Cartesian product $\mathbb{Z}_{+}^{2}\times \mathbb{Z}_{+}^{2}\times\dotsb$ we provide another $n$-options. So here the lattice path picks the next vertex uniformly that are 1-edge away. It is unclear if there is a nice correspondence with the binary tree.

Alternatively, we can try to take $\mathbb{Z}^{k+1}$ because we are basically study the number of vertices that are distance $n$ using the metric $|x_{1}|+\dotsb+|x_{k}|=n$. This number grows like $n^{k-1}$ from partition theory What are the best known bounds on the number of partitions of $n$ into exactly $k$ distinct parts?. But this goes beyond elementary.

I am trying to think if there is a natural embedding here that makes it obvious, any help is appreciated.

$\endgroup$

1

$\begingroup$

Denote $L=\lim_{n\rightarrow\infty}n^k/2^n$ and consider that $$L=\lim_{n\rightarrow\infty}\frac{(n+1)^k}{2^{n+1}}=\tfrac{1}{2}L\lim_{n\rightarrow\infty}(1+1/n)^k=\tfrac{1}{2}L\Rightarrow L=0.$$

You can find many more "proofs" at https://math.stackexchange.com/q/55468/87355

update in response to the comments: can $L$ be infinite?

if $L_n\equiv n^k/2^n$, then, $L_{n+1}=\tfrac{1}{2}(1+1/n)^k L_n<L_n$ for suffiently large $n\geq N$;

therefore, $L_n=L_{N}\frac{L_{N+1}}{L_{N}}\frac{L_{N+2}}{L_{N+1}}\cdots \frac{L_{n}}{L_{n-1}}<L_{N}$ for $n>N$.

$\endgroup$

5

$\begingroup$

Here is a completely elementary proof, without properties of logarithm, binomial expansion, or limits. On the other hand it's certainly not a proof "from the book"! Back to the first hand, we can compare any increasing exponential, not just $2^n$.

Step 1: Bernoulli's inequality: For all $x>-1$ and all integers $n \geq0$, $(1+x)^n \geq 1 + nx$. This can be proven by very elementary induction.

Step 2: Now, exponentials beat linears: given an exponential function $(1+x)^n$ with $x > 0$ (note: here $x$ is constant, and we regard this as a function of $n$) and given a slope $m$, we have $(1+x)^n > m/x$ for $n$ greater than some $n_0$, and then $(1 + x)^n > (m/x)( 1 + (n-n_0)x)$, which is a linear function of $n$ of slope $m$. We've given up control of the constant term, but we can get it back: the exponential eventually exceeds some linear function of slope $m+1$, which in turn eventually exceeds any linear function of slope $m$.

Step 3: Now fix $k$. We have in particular $(1 + x)^n > k(n+1)$ for $n$ greater than some $n_1$. For $n \geq k n_1$, let $q$ be such that $qk \leq n < (q+1)k$. We have:

$$ (1+x)^n \geq ((1+x)^q)^k > (k(q+1))^k > n^k $$

Here we have: $a^n > n^k$ for all $a>1$, $k \geq 0$, and sufficiently large integers $n$, which I think already goes a little further than the original question ($2^n > n^k$). Just in case someone is interested in "how elementary can be the proof that $a^x$ eventually exceeds any polynomial" (i.e., extending to any polynomial, and to real numbers), here it is.

Step 4: Given $a > 1$ and a polynomial $f$, let $k$ be the degree of $f$, $t$ the number of terms, and $M$ a bound for its coefficients, so that every coefficient of $f$ is between $M$ and $-M$. For large enough $n$, $a^n > n^{k+1} > Mtn^k \geq |f(n)|$.

Next: real numbers.

Step 5: In particular $a^n > (n+1)^k$ eventually. For sufficiently large $x$ we have

$$a^{x} \geq a^{\lfloor x \rfloor} > (\lceil x \rceil)^k \geq x^k $$

Finally we repeat the maneuver in step 4 to get $a^x > f(x)$ for all $a>1$, polynomials $f$, and sufficiently large $x$.

Once again, this answer has only aimed at the "completely elementary" part of the original question and in no way purports to be "from the book". I also make no suggestion about use of this presentation in instruction.

$\endgroup$

4

$\begingroup$

Here's a proof with no limits, no logarithms, and no "sufficiently large".

Let $n=4^k$. We're trying to prove that

$$ 2^{4^k} > (4^k)^k.$$

Using the properties of the exponential (which can be proven with an elementary combinatorial argument), this is equivalent to proving that

$$ 2^{4^k} > 2^{2k^2}.$$

Next, note that $2^x$ is monotonically increasing, so this is equivalent to proving that

$$4^k > 2k^2.$$

This, we'll prove via induction. As a base case, for $k=1$, we have $4>2$.

Inductively, assume that statement holds for $k$. Note that $4\ge ((k+1)/k)^2$ for all $k\ge 1$. Multiplying the two inequalities, we have

$$ 4^k \cdot 4 > 2k^2 ((k+1)/k)^2$$ $$4^{k+1} \ge 2(k+1)^2.$$

That proves the induction and completes the proof.

This proof could be made fully combinatorial by replacing every inequality with an injective mapping between strings in some alphabets, and building up from the $4^k > 2k^2$ mapping to the $2^{4^k} > (4^k)^k$ mapping.

In particular, here's an explicit $2^{2k-1} > k^2$ mapping:

We want to uniquely map from length 2 strings, where the charcters are $k$-ary, to length $2k-1$ binary strings.

Let the length 2 string be $xy$. Put a 1 in the $x$th position and in the $k+y$th position. Fill all other positions with $0$s. If $y=k$, just omit the second 1 - we can still infer it.

$\endgroup$

$\begingroup$

Here is my response to the original request for a combinatorial proof (although the proof in Zach Teitler's answer is one of my favourites).

Let $[n]^k$ be the language of $k$-letter words over the $n$-letter alphabet $[n] = \{ 0, \dots, n-1 \}$. Let $[2]^n$ be the language of $n$-letter words over the two-letter alphabet $[2] = \{ 0, 1 \}$. Of course $|[n]^k| = n^k$ and $|[2]^n| = 2^n$. Fixing $k$, we need an injective coding from $[n]^k$ into $[2]^n$ for $n$ sufficiently large.

Let $u = u_0 \dots u_{k-1} \in [n]^k$ be our input, where each $u_i \in [n]$. We want to code $u$ to $w \in [2]^{n}$. The idea is to write $w = v_{\text{positions}} v_{\text{symbols}}$, where $v_{\text{positions}} \in [2]^{k(k+1)}$ and $v_{\text{symbols}} \in [2]^{n-k(k+1)}$. At most $k$ of the $n$ available symbols appear in $u$. We use $v_{\text{positions}}$ to encode the (at most $k$) sets of positions in $u$ at which those (at most $k$) symbols appear, and we use $v_{\text{symbols}}$ to encode which symbols appear at those sets of positions.

The details are as follows. They are easy to present in picture form but I think it's worthwhile (and fun) to spell them out.

As noted above, at most $k$ of the $n$ symbols in $[n]$ are used in $u$. To each $j \in [n]$, we can associate the subset $A_j = \{ i \in [k] \, | \, u_i = j \}$. Let $j_0 < j_1 < \cdots < j_{m-1}$ be the set of $j$ such that $A_j$ is nonempty, noting that $m \leq k$.

For each $0 \leq \ell \leq m-1$, let $v_{\ell}$ be the $k$-letter word over $[2]$ giving the indicator function of $A_{j_{\ell}}$, i.e. $(v_{\ell})_{i'} = 1$ if $i' \in A_{j_{\ell}}$ and $0$ otherwise. We need $v_{\text{positions}}$ to have length exactly $k(k+1)$, so if in fact $m < k$, then for $m \leq \ell \leq k-1$ let $v_{\ell} = 0^k$.

So far we have $k$ blocks of length $k$. For $n$ sufficiently large, the following algorithm successfully defines a unique special index $0 \leq \ell^* \leq m$:

- If $j_0 > k(k+1) - 1$: set $\ell^* = 0$ and terminate the algorithm.

- For each $1 \leq \ell \leq m-1$: If $j_{\ell} - j_{\ell-1} > k(k+1)$ then set $\ell^* = \ell$ and terminate the algorithm.

- Set $\ell^* = m$.

Note that if $\ell^* = m$, then $j_{m-1} < n - k(k+1) - 1$. For $0 \leq \ell \leq k-1$, let $a_{\ell} = 1$ if $\ell = \ell^*$ and $0$ otherwise. Let $v_{\text{positions}} = a_0 v_0 a_1 v_1 \dots a_{k-1} v_{k-1}$.

Now, the naive way to define $v_{\text{symbols}}$ is as the word giving the indicator function of the set $\{ j_0, \dots, j_{m-1} \}$, i.e. $(v_{\text{symbols}})_j = 1$ if $A_j \neq \emptyset$ and $0$ otherwise. Call that naive choice $v'_{\text{symbols}}$.

The trouble is that $v'_{\text{symbols}}$ has length $n$, and we have already reserved a block of length $k(k+1)$ for $v_{\text{positions}}$, so we need to compress $v'_{\text{symbols}}$ a bit. However, if $n$ is sufficiently large, then by pigeonhole, as noted before the algorithm above, $v'_{\text{symbols}}$ contains at least one block of $0$'s of length at least $k(k+1)$: from $0$ to $j_0 - 1$ if $\ell^* = 0$; from $j_{\ell^*-1}$ to $j_{\ell^*}-1$ if $1 \leq \ell^* \leq m-1$; or from $\ell^*$ to $n-1$ if $\ell^* = m$. Choose the block of $0$'s indicated by $\ell^*$ and shorten it by $k(k+1)$ to obtain $v_{\text{symbols}}$. This completes the construction of $w$.

To recover $u$ from $w$: break $w$ into $v_{\text{positions}}$ $v_{\text{symbols}}$, which is unambiguous since their lengths are fixed. Look at the $a_{\ell}$'s in $v_{\text{positions}}$ to determine $\ell^*$ and thus to decide which block of $0$'s in $v_{\text{symbols}}$ to extend by $k(k+1)$ more $0's$, thus recovering $v'_{\text{symbols}}$. Look through $v'_{\text{symbols}}$ to find which symbols $j \in [n]$ were used in $u$. Where $j = j_{\ell}$, place symbol $j \in [n]$ at all the positions $i \in [k]$ where $v_{\ell} = 1$.

$\endgroup$

3

$\begingroup$

$f(x)\gg g(x)$ if $f'(x)\gg g'(x)$. The derivatives of an exponential are exponential, but the derivatives of any polynomial are eventually $0$. So for $f(x)=2^x$ and $g(x)=x^k$, the fact that $f^{(k+1)}(x)\gg 0=g^{(k+1)}(x)$ gives the desired conclusion.

$\endgroup$

1

$\begingroup$

The following argument is not elementary, but nice and simple, so I feel like sharing.

First observe that the function $x/\log x$ is increasing for $x>4$, whence it exceeds $4/\log 4$ for $x>4$. This is equivalent to $4^x>x^4$ for $x>4$. Taking the square-root of both sides, we see that $2^x>x^2$ for $x>4$. Now assume that $2^{n/k}>\max(16,k^2)$. Then $n/k>4$ and $2^{n/k}>k^2$. Applying our initial observation to $x=n/k$, it also follows that $2^{n/k}>n^2/k^2$. Hence in fact $2^{n/k}$ exceeds the geometric mean of $k^2$ and $n^2/k^2$, which is $n$. In other words, $2^n>n^k$.

$\endgroup$

2

$\begingroup$

I will be far more concrete than other answerers:

Suppose you increment $x$ from $1\text{ zillion}$ to $(1\text{ zillion}) + 1.$ Then $2^x$ gets twice as big, whereas $x^n$ grows by an amount that, although huge, is microscopic compared to the immense size of $(\text{1 zillion})^n.$

I would try to ascertain that the student understands that that is the central idea before addressing the question of just how we know that that is true.

Even students who get straight $\text{“A}{+}\text{”s}$ in algbera and are magnificently adept at all a techniques in algebra that students are asked to master usually do not understand anything by means of algebra. For example, suppose such a student claims to know that $1+\prod_{p\in S} p$ fails to be divisible by any of the members of $S,$ and they demonstrate that they know all the steps in a proof of that fact, and they understand that proving that fact is the purpose of those steps. Then you say $1+(2\times3\times7) =43$ cannot be divisible by $7$ since the next number after $42$ that is divisible by $7$ is $42+7$ and the last one before that that is divisible by $7$ is $42-7,$ and for the same reason, $1+(2\times3\times7)$ cannot be divisible by $2$ or by $3,$ and they say they never understood that before. I've seen this happen hundreds of times (although only a few times with a proof of this particular proposition). The fact that the point of the algebra was to bring them to the point of understanding that which they later came to understand only via concrete examples like this is simply not present in their minds at all.

$\endgroup$

23

$\begingroup$

Let's apply a simple inequality:

Theorem 0 Let real variables satisfy condition $\ 0<D<b<a.\ $ Then

$$ \frac ab\ <\ \frac{a-D}{b-D}. $$

Thus, we see that (for $n>1$):

$$ \frac{n^k}{(n-1)^k}\ < \,\ \frac{\prod_{j=0}^{k-1}(n-j)}{\prod_{j=1}^k(n-j)}\ =\ \frac n{n-k} $$

hence

$$ \frac{n^k}{(n-1)^k}\ <\ \frac 32\qquad \text{whenever} \quad n\ge 3\cdot k. $$

It follows that for $\ n > 3\cdot k$,

$$ n^k\,\ <\,\ (3\cdot k)^k\,\cdot\ \left(\frac32\right)^{n-3\cdot k} $$

$$ =\ (3\cdot k)^k\,\cdot\ \left(\frac23\right)^{3\cdot k}\, \cdot \, \left(\frac32\right)^n\,\ =\,\ C_k\cdot \left(\frac32\right)^n $$ for $$ C_k\ :=\ (3\cdot k)^k\,\cdot\ \left(\frac23\right)^{3\cdot k}. $$

Finally,

$$ \frac {n^k}{2^n}\,\ <\,\ C_k\cdot\left(\frac34\right)^n\ $$

so that $$ \lim_{n=\infty} \frac {n^k}{2^n}\ =\ 0. $$

$\endgroup$

$\begingroup$

If you're willing to move to real analysis, you can show by an elementary variational argument that $f~:~x\geq 2k+2 ~~\longmapsto ~~x^{(k+1)} 2^{-x}$ is decreasing, since the derivative is $(k+1-x\ln 2)\frac{f(x)}{x}$, thus bounded from above by $f(2k+2)$. You don't get the exponential decay, though, and you need to know that $2^x=\exp(x\ln 2)$ and $\ln (2) > 1/2$.

$\endgroup$

2

$\begingroup$

Let $0<q<1$ and $k \geq 1$. Pick $ \epsilon >0$ with $r:= q(1+\epsilon) <1$. By the Bernoulli inequality $$0 \leq q^n n^k = \frac{n}{(1+\epsilon)^n}(n^{k-1}r^n)\leq\frac{n}{1+n\epsilon}(n^{k-1}r^n)\leq \frac{1}{\epsilon} (n^{k-1}r^n).$$ By induction on $k$, the second factor tends to $0$.

$\endgroup$

0

$\begingroup$

By the binomial theorem $$ 2^{\frac{n}{k}} =(1+\sqrt[k]{2}-1)^n > \binom{n}{2}(\sqrt[k]{2}-1) $$ Now, for $n$ large enough (this can be calculated explicitely) we have $$ \binom{n}{2}(\sqrt[k]{2}-1) >n $$

$\endgroup$

$\begingroup$

For $k\ge1 $ and $$n\ge 4k^2$$ (that is $\frac{2k}{\sqrt n}\le 1$) set $x_1=\dots=x_{2k}=\sqrt n$ and $x_{2k+1}=\dots=x_n=1$. The arithmetic mean of these $n$ numbers is $\frac{ 2k\sqrt n +n-2k}n\le \frac{2k}{\sqrt n}+1\le2$, the geometric mean is $n^{k/n}$ and the arithmetic-geometric mean inequality gives $$2^n\ge n^k.$$

$\endgroup$

1

$\begingroup$

It suffices to show that $2^x > kx$ for all large $x$, because then we can take the $k$th power of both sides: $2^{kx} > (kx)^k$ for all large $n = kx$.

At least for $x$ an integer, $2^x > kx$ is easy to prove by induction on $x$. We can get the base case by noting that if $m \ge 3$ then $2m < 2^m$ and hence $(2m)^2 < (2^m)^2 = 2^{2m}$; thus $2^k > k^2$ for $k \ge 6$, and we can take $x=k$ as the base case for $k\ge 6$.

$\endgroup$

2

$\begingroup$

First establish the simplest case $2^{m} > m^{2}$ for $m > 4$, for example by induction: the inequality holds for $m = 5$ and $2^{m+1} = 2 \cdot 2^m > 2 m^2 = m^2 + m^2 > m^2 + 2m + 1 = (m+1)^2$, since $m^2 > 3m > 2m+1$ for $m \geq 5$.

Next, given $k > 1$, show that there are arbitrarily large $n$ for which $2^n > n^k$. It suffices to take $n := 2^{ak}$ for $ak > 5$, since $2^{n} = 2^{(2^{ak})} > 2^{((ak)^2)} = n^{ak} > n^k$.

Finally, if $n$ is large enough, then $(n+1)^{k} / n^{k} = (1+\frac{1}{n})^{k} < 2$, while $2^{n+1} / 2^{n} = 2$, so $2^n > n^k$ implies $2^{n+1} > (n+1)^k$. The required inequality therefore holds for all large enough $n$.

$\endgroup$

$\begingroup$

For some fixed positive integer $k$, let $n^k < 2^n < n^{k+1}$

Now if we go from $n$ to $n+1$ and take ratios we get: $\frac{2^{n+1}}{2^n} = 2 > \frac{(n+1)^{k+1}}{n^{k+1}}= \left(1 + \frac{1}{n}\right)^{k+1} = 1$ for large $n$ and fixed $k$.

$\endgroup$

$\begingroup$

I would suggest considering instead the stronger statement that $n^k/2^n \to 0$. (This would of course necessitate an explanation of what it means for a function to converge to zero as the argument tends to infinity.) Since $n^k/2^n \to 0$ implies $n^{2k}/2^n \to 0$ by squaring, we may reduce to $k=1$.

We thus have to show that $n/2^n \to 0$. We can represent this visually by comparing $n=\underbrace{1+1+\ldots+1}_{\textrm{$n$ summands}}$ to $2^n=\underbrace{2 \times 2 \times \ldots \times 2}_{\textrm{$n$ factors}}$. Now the first expression is always less than the first, and it is intuitively completely obvious that the ratio between the two can be increased indefinitely, since one makes a number increase faster by repeatedly multiplying by $2$ than by repeatedly adding $1$. This should be a convincing argument for anyone who's played around with a calculator.

In fact, I think I would leave it at that. It's not a "proof", of course, but all the same, it would convince most people that the statement must be true (and hence that a proof must exist).

Of course, finishing the proof is not hard either, since $\frac{n+1}{n}$ decreases monotonically (and is equal to $3/2$ at $n=2$) whereas $\frac{2^{n+1}}{2^n}=2$.

In fact since $\frac{n+1}{n} \to 1$ this argument proves that the ratio between the two expression is $> C_{\epsilon} 2^{n(1-\epsilon)}$ for any $\epsilon>0$, implying $n < C_{\epsilon}^{-1} 2^{\epsilon n}$. From this, you easily get the statement for general $k$.

$\endgroup$

$\begingroup$

$n \ge k^2 \implies n \ge k \sqrt{n} \implies 2^{n} \ge 2^{k \sqrt{n}}$. And $\sqrt{n} \ge \log_2(n)$ for large enough $n$ so $2^{k \sqrt{n}} \ge 2^{k \log_2(n)} = n^k$.

$\endgroup$

2

$\begingroup$

Lemma: Assume $\Delta f(x) > \varepsilon > 0$ for all $x$ greater than some constant. Then $f(x) > \varepsilon’ > 0$ for some $\varepsilon'$ and all $x$ greater than some constant.

Proof: From the condition $\Delta f(x) > \varepsilon > 0$, for any $K$, there exists an $N$ such that, for all $n \ge N$, $\sum_{i=0}^{n} \Delta f(x) = f(n+1) - f(0) > K$. Choose $K$ such that $K+f(0)>0$, and the conclusion follows.

Next, note that $\Delta^n2^x = 2^x$ for all $n$ and that there exist a $p$ such that $\Delta^p g(x) = 0$ for $g$ any polynomial. This implies that $\Delta^p(2^x - g(x))=2^x$. Applying the lemma gives that $$ 2^x > g(x) $$ for any polynomial $g(x)$ and $x$ sufficiently large.

$\endgroup$

0

You must log in to answer this question.

Explore related questions

See similar questions with these tags.