Why the Bayeux Tapestry is an important relic of London history.

We have almost no visual record for about two-thirds of London's history. The Romans left us nothing except crude depictions of individual buildings on some of their coins. The Anglo-Saxons didn't get that far (though, see below). The only meaningful image of London before the 13th century comes from the Bayeux Tapestry.

The origins of the Tapestry (actually an embroidered artwork) are still debated. Some historians will tell you that it was probably created in Normandy. The majority, however, now believe it to be the work of Kent-based needleworkers of Anglo-Saxon background, working in the 1070s not long after the Conquest.

Either way, much of the Tapestry is 'set' in England. An early scene sees Harold riding to Bosham in Sussex. We glimpse both Edward the Confessor and his successor King Harold sitting in their throne rooms, most probably in London. And the tapestry famously concludes with the fateful battle near Hastings.

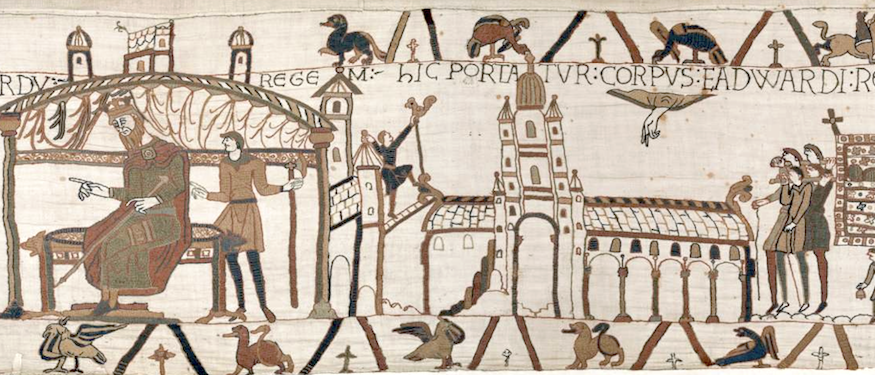

Scene 26, though, gives us our best eyeful of London:

The stitched text above reads "hIC PORTA TVR CORPVS EADVVARDI RЄGIS AD ЄCCLЄSIAM SANCTI PETRI APOSTOLI". This translates as: "Here the body of King Edward is carried to the church of St Peter the Apostle". You might know it as Westminster Abbey, so named to distinguish it from the 'east minster' of St Paul's. The embroidered image in the Bayeux Tapestry is the only surviving depiction of the abbey from this period.

The church was brand new at the time, commissioned by Edward the Confessor and consecrated a few days before his death (in his sickbed absence). Indeed, the Tapestry seems to be showing us that consecration. The hand-of-God, reaching down from above, and the man placing the weathervane on the roof, both point to the church coming into its holy commission. We can therefore pinpoint the exact date of this depiction. The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle tells us that "the Church hallowing was on Childer-mass Day", which is to say 28 December 1065.

Are we looking at an accurate representation of the new abbey? Nobody knows. Buildings were usually depicted stylistically in this period, with little care for architectural accuracy. Chances are that the Abbey was stitched by artists who had never seen it, perhaps from a vague description like 'It's a big Romanesque church with towers'. Then again, we can't rule out a close likeness. Parts of the supporting columns survive in the crypt of the current Abbey (built in the 13th century), and their girth suggests this building must have been one of the most impressive in England at the time.

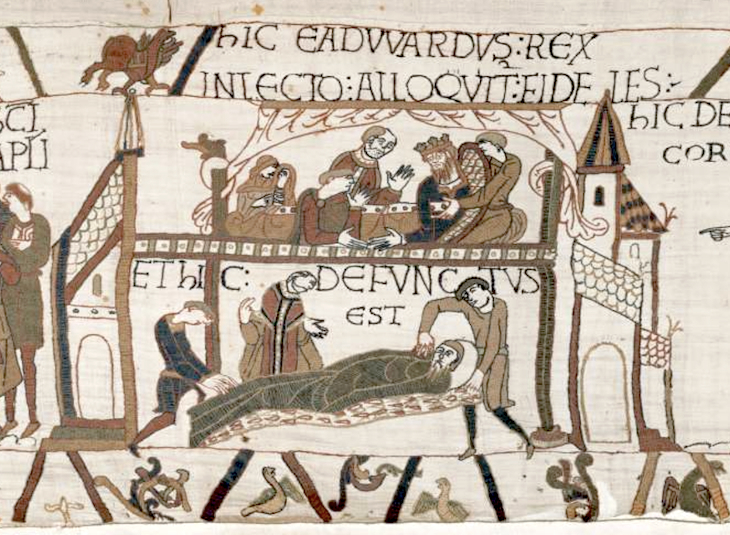

The Abbey might not be the only representation of London in the Tapestry. The very first scene depicts King Edward ('EDWARD REX') sitting under huge wooden roof beams, apparently in his palace.

Like monarchs of all ages, Edward had more than one palace, so in theory the scene could be in Windsor or Winchester, or even Havering. But Westminster Palace was the chief seat of Edward, and so this is the likely setting of this first scene. If that is the case, then the Bayeux Tapestry shows us not only the earliest image of Westminster Abbey, but also of the Palace of Westminster (which would eventually evolve into the Houses of Parliament, though it is still technically a palace). Like the Abbey, it's probably a stylised representation rather than an accurate depiction.

The Tapestry gives us two further London scenes, though neither holds much detail of the physical buildings. The first shows King Harold's Coronation in (almost certainly) Westminster Abbey:

Harold's was the first Coronation performed in the Abbey. Every King and Queen of England (and later the UK) has been anointed in the building since, with the exceptions of Edward V and Edward VIII (disappeared and abdicated, respectively, before the ceremony could take place).

Harold is also depicted on his throne, again presumably at Westminster:

This scene is fascinating in its own right, but look above and you'll see a strange, fiery body flying over his throne room. The text (spread across the last two images) says "These men marvel at the star" (referring to the pointing people in the previous panel). What we're seeing here is Halley's Comet, or the periodic comet that would come to be known by that name 700 years later.

This is the earliest certain depiction of Halley's Comet anywhere in the world. Appropriately, a memorial stone to Edmond Halley, shaped like the comet, can be found in the cloisters of Westminster Abbey:

At its centre is a depiction of the Giotto space probe, which had a close encounter with the comet on its 1986 pass. So now you can mildly bamboozle your friends by telling them that Westminster Abbey contains an image of a space craft.

The Bayeux Tapestry is, of course, one of the most important primary sources of the Battle of Hastings, and the momentous events leading up to it. But it also holds great significance in the history of London. It features the first depictions of Westminster Abbey, the Palace of Westminster and the comet first understood by Londoner Edmond Halley. It's yet another filter through which we can enjoy the Tapestry, when it comes to the British Museum later in 2026.