Abstract

Background

Statin therapy has been associated with increased risk of type 2 diabetes (T2D). We investigated the relationship between Low-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol (LDL-C) plasma concentrations and incident T2D and evaluated the modifying effect of statin therapy in a large population-based cohort.

Methods

Individuals free of T2D and cardiovascular disease at baseline were followed longitudinally for the development of new-onset T2D. Cox proportional hazards models were applied to evaluate the associations of LDL-C levels and statin therapy with T2D risk.

Results

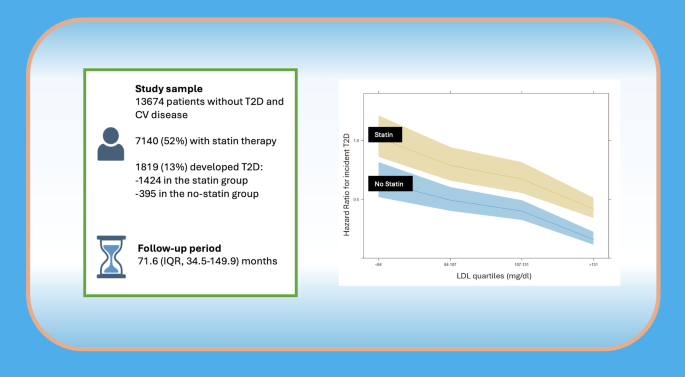

From a population of 202,545 individuals, we selected 13,674 participants free of T2D and cardiovascular disease (of whom 52% were on statins), who were followed for a median of 71.6 months (IQR 34.5–149.9), during which 1,819 (13%) developed incident T2D. Cox multiple regression analysis revealed a significant inverse association between LDL-C plasma levels and incident T2D (p < 0.001). When stratifying LDL-C into quartiles [i.e. low (< 84 mg/dL), medium (≥ 84 to < 107 mg/dL), high (≥ 107 to < 131 mg/dL), and very high (≥ 131 mg/dL)], we observed that patients with LDL-C < 84 mg/dL had the highest risk of developing T2D. The interaction between statin therapy and T2D incidence was significant only in the very high LDL-C group, where statin users had a greater risk than non-users (p = 0.018); in the other three LDL-C groups, statin therapy did not significantly modify the association between LDL-C and T2D risk.

Conclusions

Taken together, our findings demonstrate a strong inverse association between LDL-C and incident T2D in the general population. The increased risk of T2D at lower LDL-C levels appears to be independent of statin use, supporting the role of LDL-C as a potential biomarker of T2D susceptibility.

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Research insights

What is currently known about this topic?

-

Statins can increase risk of incident T2D.

-

Genetic studies link low LDL-C to higher T2D risk.

-

LDL-C may influence diabetes risk independent of therapy.

What is the key research question?

-

Does plasma LDL-C associate with incident T2D independent of statin therapy?

-

Low LDL-C (< 84 mg/dL) predicts higher T2D risk in the general population.

-

Statin therapy increases T2D risk only at very high LDL-C levels.

-

LDL-C inversely associates with T2D risk regardless of statin use.

How might this study influence clinical practice?

-

LDL-C may serve as a biomarker for T2D risk assessment.

Introduction

Mounting evidence indicates that statins can cause a moderate dose-dependent increase in new diagnoses of type 2 diabetes (T2D) [1, 2]. The increased rate of incident T2D during statin treatment has long been considered as a side effect, although the exact pathogenetic mechanisms underlying this phenomenon have never been identified. On the other hand, a similar increase in T2D is associated with LDL-C-lowering alleles in HMGCR (3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl coenzyme A reductase) [3] and a meta-analysis [1] has demonstrated that exposure to LDL-C-lowering genetic variants in or near NPC1L1 (Niemann-Pick C1-Like 1) and other genes is associated with a higher risk of T2D, providing insights into the pathogenesis of this effect of all LDL-C-lowering therapies.

Numerous genetic studies [4,5,6,7] have yielded informative observations between LDL-C and T2D. In particular, familial hypercholesterolemia, a monogenic disease characterized by elevated plasma levels of LDL-C and increased risk of coronary artery disease (CAD), is associated with significantly lower risk of developing T2D, while LDL–C lowering genetic variants increase the risk of T2D [5, 6]. More recently, Ravi and coworkers analyzed in a large prospective population the extent to which genetic factors across the cholesterol spectrum are associated with incident T2D. A Cox proportional hazards regression model adjusted for age, sex, genotyping array, lipid-lowering medication use, and the first 10 genetic principal components fitted to assess the association between LDL-C genetic factors and incident T2D, demonstrated that LDL-C and T2D risks were inversely associated across genetic mechanisms for LDL-C variation [8]. Furthermore, a drug target Mendelian randomization study to assess causal associations of genetically proxied inhibition of HMGCR, PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9), and NPC1L1 with blood pressure (BP) and fasting glucose revealed that genetically proxied inhibition of HMGCR is significantly associated with low BP and high fasting glucose, while there is no effect of PCSK9 and NPC1L1 inhibition on BP or fasting glucose [9].

Although the increase in T2D incidence has been hitherto considered a possible side effect of statins, also linked to the increase in body weight, genetic studies suggest that the reduction in plasma LDL-C concentration could be linked to an increase in incident T2D. This observation could allow the hypothesis that the increase in incident T2D related to statin therapy may be the mere consequence of the reduction in LDL-C plasma concentration through mechanisms that have yet to be clarified.

However, not all studies on genetic variants associated with higher LDL-C levels have shown an association between low LDL-C plasma levels and increased T2D risk. To the best of our knowledge, the correlation between individual LDL-C plasma levels and incident T2D risk during a very long follow up in the general population has not been investigated.

Thus, we designed a dedicated study to assess the relationship, if any, between LDL-C plasma levels and the incidence of new T2D in a large population, and to define the impact of statin therapy on this phenomenon dividing the population according to the presence or not of statin therapy.

Methods

We conducted a population-based cohort analysis using the COMEGEN database (“COoperativa di MEdicinaGENerale”: General Medicine Cooperative), a network of primary care physicians operating within the Naples Local Health Authority ("ASL Napoli 1 Centro") under the Italian Ministry of Health. As we previously detailed [10], COMEGEN currently comprises 140 general practitioners who are interconnected through a shared electronic medical record system. This infrastructure has enabled the creation of a comprehensive real-world dataset encompassing medical records for over 200,000 adult patients. These records are updated on a daily basis by each physician, who inputs all data from his/her outpatient clinical activities [11].

The demographic distribution of patients under the care of COMEGEN physicians mirrors that of the general population of Naples, as reported by the National Institute of Statistics (ISTAT), showing no significant variation in geographic representation or age stratification [12]. The database captures diagnoses based on the International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10), along with standardized codes for all prescribed diagnostic procedures. Pharmaceutical prescriptions are systematically recorded, including the prescription date, commercial and generic names, active compounds, dosage, and administration routes.

Additionally, the database includes detailed information on vital signs, anthropometric measures such as weight, height, body mass index (BMI), and waist circumference, as well as chronic conditions, medical consultations, hospital admissions, emergency room visits, dispensed medications, diagnostic tests, vaccinations, and mortality data, including date and cause of death. The precision in tracking person-time within the COMEGEN database supports robust calculation of incidence rates, providing exact dates for cohort entry, data contribution, death, follow-up termination, and observation conclusion.

The dataset also includes demographic profiles, clinical characteristics, laboratory results, and pharmacological treatments. This wealth of information allows for near real-time evaluation of patient care, encompassing clinical pathways, treatment outcomes, diagnostic utilization, pharmacological management, and the complexity and comorbidity burden within the patient population [13].

Study sample

In the period between January 2010 and March 2025, we selected all patients with age between 18 and 90 years with available physical measurements including weight, height, BMI, heart rate and blood pressure; biochemical measurements included serum creatinine fasting blood glucose, total-cholesterol, HDL and LDL-cholesterol, triglycerides, serum transaminases, hemoglobin and platelet counts; medical conditions included coronary/carotid events, diabetes, hypertension, and smoking status. Current chronic therapies were categorized into three classes: antihypertensive agents, antidiabetic agents, lipid-lowering drugs.

Inclusion criteria: Age > 18 or < 90-year-old; availability of information on diabetes, hypertension and CV history; availability of clinical and demographic data.

Exclusion criteria: patients with conditions that could limit life expectancy (cancer, peripheral vascular disease, venous thrombosis, abdominal aortic aneurysm, valvular heart disease, and dementia); patients with liver cirrhosis, which has been linked to nontrivial safety concerns that could discourage the use of statins; history of cardiovascular (CV) diseases or diabetes, age < 18 or > 90-year-old; missing information on diabetes, hypertension and CV history, clinical, or demographic data.

The main outcome of the study was the new diagnosis of T2D assessed by the ICD-X codes E11 (“T2D”) and E13X (“Other specified diabetes mellitus”) defined as at least two measurements (not necessarily consecutive) of fasting plasma glucose concentration of 126 mg/dl or higher or at least one HbA1c value of 6.5% or higher, or prescription of antidiabetic therapies for more than 30 days, as previously reported [14]. Diagnoses of T1D, including the specific code E08 were excluded.

At the beginning of the observation period, we removed from the study cohort all individuals with a record of HbA1c > 6.5% (48 mmol/mol), individuals with fasting plasma glucose allowing T2D diagnosis or a previous diagnosis of T2D as defined by ICD-X codes E08.X to E13.X, or prescription record of antidiabetic medications for more than 30 days, as well as those with an history of cardiac or cerebral events.

CV risk factor and disease assessment

Data on demographics and risk factors were recorded at enrollment, including age, sex, race, history of myocardial infarction, diabetes, and hypertension. Body mass index was calculated based on the values of body height and weight. Fasting plasma glucose was assessed by standard methods; prevalent diabetes was defined as reported above. Hypertension was defined as a record of systolic blood pressure > 140 mmHg and/or diastolic blood pressure > 90 mmHg, or a previous diagnosis of hypertension as defined by the ICD-X (code I-10), or prescription record of anti-hypertensive medications for more than 30 days. Lipid measurements on fasting blood samples were implemented at each study examination; triglycerides and total cholesterol levels were measured enzymatically, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) was obtained after precipitation with dextran sulfate/magnesium chloride, and LDL-C was calculated applying the Friedewald equation [16]. For very high levels of triglycerides (> 400 mg/dL), direct LDL-C measurement was assessed. Liver function was also assessed by measuring GOT (Glutamic-Oxaloacetic Transaminase) and GPT (Glutamic-Pyruvic Transaminase). All data were collected at each visit (at least two visits per year); how often they were measured and the time between visits was not standardized but followed the physician’s directions. Of note, physicians asked patients about drug compliance and adverse reactions to confirm drug exposure and tolerability at each visit. The physician augmented the dosage of a statin or other prescribed comedication(s) when LDL-C concentrations had not sufficiently decreased.

The following statins were administered alone or in combination with ezetimibe: atorvastatin, fluvastatin, lovastatin, rosuvastatin, simvastatin and pravastatin, with the dosage adjusted during the follow-up if necessary, according to efficacy and tolerability.

Statistical analysis

Data are reported as mean (SD) or absolute frequencies (percentage). For time-to-event outcomes, Cox regression models were used to identify variables associated with the incidence of T2D. The follow-up time was defined as the time from enrollment until the end of follow-up (March 2025), incident T2D, incident CV event or death, or loss to follow-up, whichever came first. To adjust for the difference in baseline characteristics between groups, we used clinically available predefined variables, which were selected on the basis of previous reports [15] where the diabetic risk score was defined. Thus, we selected the following variables for the analyses after accounting for the other variables’ completeness, accuracy, missing rate, recent measurement: age, sex, BMI, fasting plasma glucose, creatinine, and hypertension.

Variables that showed statistical significance at the crude models were added to the adjusted models. In order to investigate the possible moderating effect of statin therapy on the relationship between LDL-C plasma concentration and T2D, an interaction term (product term) was added to a separate adjusted model. The proportional hazard assumption was tested using the Schoenfeld residuals. Difference between means among LDL-C groups was computed using one-way ANOVA. Difference between proportions among LDL-C groups was computed using chi-square test. Pairwise comparisons (post-hoc analyses) were conducted adjusting for multiple comparisons using Bonferroni correction. Sensitivity analyses to validate the results included running all univariate and multivariable models considering LDL-C plasma concentration as a continuous and as categorical variable, removing or keeping all outliers and performing univariate regressions including only complete cases versus performing multiple imputation for the variables with a percentage of missing values < 30%. Results were not different in any of these cases; therefore the complete case analysis is reported. Analyses were performed using R statistical software version 4.4.0. A two-tailed p-value < 0.05 was considered significant for all analyses.

Results

We analyzed anonymized electronic health records from 202,545 patients. After excluding individuals according to predefined exclusion criteria, the final cohort included 13,674 participants aged between 19 and 90 years (Supplementary Fig. 1). Among these, the mean (SD) age was 62 (17) years, and 58% were male. The mean (SD) baseline LDL-C was 105 (33) mg/dL (to convert to mmol/L, multiply by 0.0259), total cholesterol was 187 (47) mg/dL, HDL-C was 51(17) mg/dL, triglycerides were 104 (57) mg/dL, liver function was GOT 21 (6) mU/mL and GPT 20 (7) mU/mL and 52% of the cohort were prescribed statin therapy. Over a median follow-up of 71.6 months (IQR, 34.5–149.9), 1,819 individuals (13%) developed incident T2D.

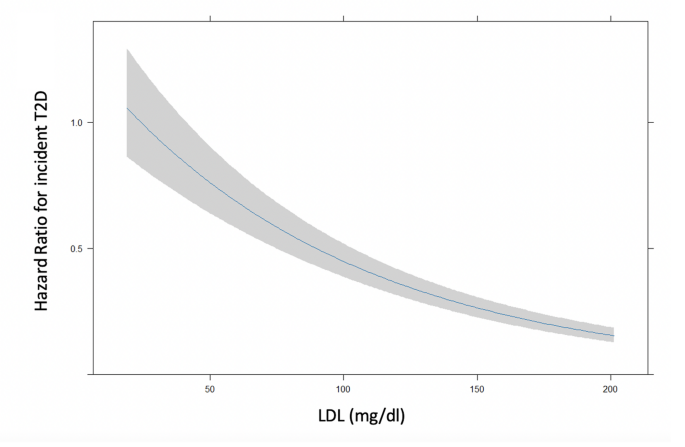

Univariate regression analysis identified significant associations between incident T2D and age, sex, fasting plasma glucose, BMI, serum creatinine, LDL-C, statin therapy, and hypertension. These variables were included in a multivariable Cox regression model (Table 1), where all predictors except sex remained statistically significant. Notably, a significant inverse association between LDL-C levels and incident T2D was observed (p < 0.001), indicating that lower LDL-C levels were associated with higher T2D risk (Fig. 1).

Risk of incident T2D in terms of adjusted hazard ratio according to LDL-C levels considered as continuous variable adjusted by age, sex, BMI, blood glucose, creatinine, and hypertension. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence bands

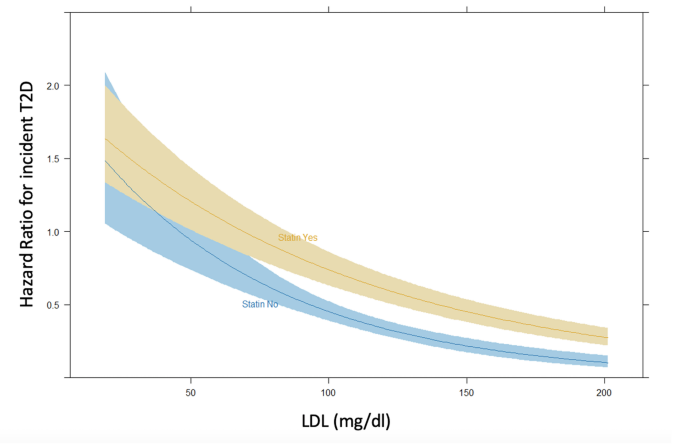

The cohort was then stratified by statin therapy. Table 2 presents demographic and clinical characteristics of the two groups. Statin users were older, had higher BMI, fasting plasma glucose, and serum creatinine levels, as well as a higher prevalence of hypertension, and lower LDL-C levels. Incident T2D developed in 1,424 patients (20%) receiving statins and 395 patients (6%) not on statin therapy (p < 0.001). Additionally, a significant interaction between statin therapy and LDL-C levels on T2D risk was identified (aHR 1.0, 95% CI 1.0–1.01, p = 0.017; Fig. 2).

Interaction of statin therapy on incident T2D according to LDL-C levels considered as continuous variable in the multivariable model adjusted by age, sex, BMI, blood glucose, creatinine and hypertension

To further examine the relationship between LDL-C levels and T2D risk, participants were grouped by LDL-C concentration based on quartiles: low (< 84 mg/dL), medium (≥ 84 to < 107 mg/dL), high (≥ 107 to < 131 mg/dL), and very high (≥ 131 mg/dL). Clinical characteristics for each group are reported in Table 3. The low LDL-C group included older participants with higher BMI, a lower percentage of men, and a higher prevalence of hypertension and statin use.

During follow-up, a total of 1,819 incident T2D cases were recorded: 787 in the low LDL-C group (27.6 cases per 1,000 person-years), 489 in the medium group (17.4 per 1,000 person-years), 347 in the high group (13.5 per 1,000 person-years), and 196 in the very high group (8.4 per 1,000 person-years). Compared to all others, the incidence of T2D was significantly lower in the very high LDL-C group (all p values < 0.001).

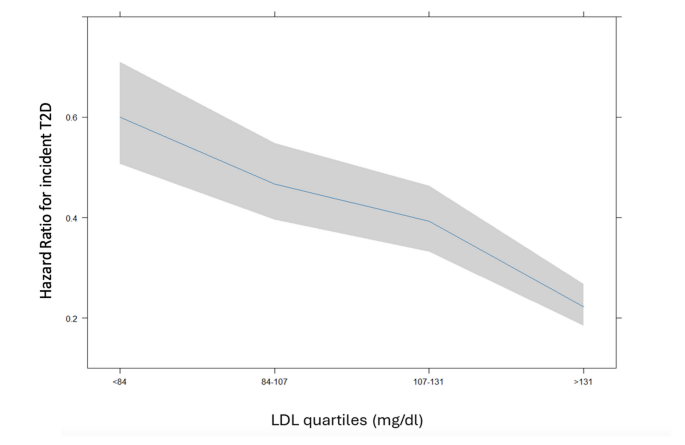

Cox univariate and multivariable regression analyses stratified by LDL-C group (Table 4) confirmed that patients with LDL-C < 84 mg/dL had the highest risk of incident T2D. In this group, T2D risk declined sharply as LDL-C increased, while in the other three groups, risk declined more gradually with increasing LDL-C levels (Fig. 3).

Risk of incident T2D in terms of adjusted hazard ratio according to LDL-C levels in 4 categories by quartiles adjusted by age, sex, BMI, blood glucose, creatinine, and hypertension. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence bands

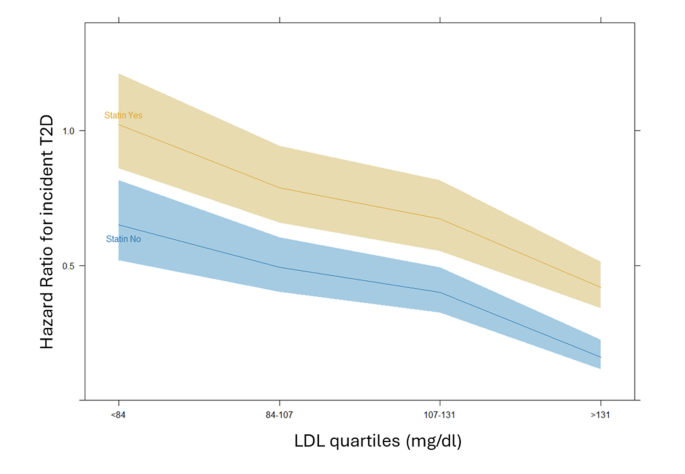

When statin interaction was included in an additional multivariable model, only the very high LDL-C group (≥ 131 mg/dL) displayed a significantly elevated risk of T2D in patients on statins compared to those not taking statins (interaction term aHR 1.68, 95% CI 1.09–2.58, p = 0.018). In contrast, the interaction between statin use and T2D risk was not statistically significant in the other LDL-C groups. This finding, in other words, highlights how, while the risk of T2D increases with statin usage by a constant amount in every LDL-C group, this risk is instead different and significantly increased in the very high LDL-C group only. In fact, as can also be observed in Fig. 4, while the statin usage significantly determines an increased risk of T2D at all categories (evidenced by the confidence bands) the steepness of the line plot only deviates, although slightly, at the last category.

Interaction of statin therapy on incident T2D according to LDL-C levels in 4 groups adjusted by age, sex, BMI, blood glucose, creatinine, and hypertension. Shaded areas represent 95% confidence bands

In order to confirm the results of the interaction obtained with the previous model, we have run four independent multivariable Cox regression models to investigate the association between statin and T2D risk adjusted by age, sex, BMI, blood glucose, creatinine and hypertension within each LDL-C category. We observed a significant effect of statin on T2D in all four groups (all p values < 0.001), but in the group with very high LDL-C, as expected by the previously reported interaction analysis, the risk is markedly higher and over twofold compared to the low LDL-C group (respectively, calculated by separated models, in the low LDL-C group the statin aHR was 1.75, 95%CI 1.39–2.20; medium LDL-C group aHR 1.63, 95%CI 1.32–2.00, high LDL-C group aHR 1.54 95%CI 1.22–1.95, very high LDL-C group aHR 2.41, 95%CI 1.64–3.53).

Discussion

The main findings of this study include: first, within a general population, an inverse relationship exists between plasma LDL-C levels and the risk of incident T2D. Second, statin therapy significantly modifies this association in the whole population, such that for any given LDL-C concentration, individuals receiving statins have a higher probability of developing T2D compared to those not on treatment. Third, when the population was stratified into four groups based on LDL-C levels, the interaction between statin use and incident T2D risk reached statistical significance only in the group with very high LDL-C concentrations.

Previous observations suggest that both monogenic and polygenic factors affecting LDL-C polygenic risk scores are inversely associated with T2D risk, and that the magnitude of this risk correlates with the degree of genetic LDL-C perturbation [8].

Various genetic loci, including HMGCR, APOE, PCSK9, NPC1L1, PNPLA3, TM6SF2, GCKR, and HNF4A genes, are known to harbor variants exerting opposing effects on LDL-C and T2D [7, 17]. Nonetheless, genetic findings reveal that not all variants have opposing effects on LDL-C levels and T2D risk [18]. LDL-C lowering variants in ABCG5/G8 and LDLR genes did not present alteration in T2D risk and subsets of LDL-C lowering alleles provide a stronger prediction against T2D [17].

In this scenario, heterogeneous pathways of lipid and glucose metabolism may underlie the interaction between LDL-C–lowering mechanisms and the risk of T2D. Further research is needed to clarify the pathophysiological mechanisms driving this phenomenon. However, the present study is the first to investigate this relationship in a large, unselected general population rather than relying on biobank participants or genetic meta-analyses. Unlike previous approaches, the primary care database employed here provides a representative sample of the general population. In Italy, all citizens are assigned a primary care physician (family doctor) who follows them even in the absence of specific pathologies. Consequently, the database includes not only patients with diagnosed illnesses but also individuals without any known disease (or at least not aware of one), who are nonetheless monitored over particularly long follow-up periods. This methodological distinction is important, as the association between LDL-C and T2D risk may vary depending on the underlying genetic determinants, indicating that findings from genetic studies cannot be directly generalized to real-world populations. Within this context, the current study demonstrates a clear inverse association between LDL-C levels and incident T2D over extended follow-up, with the highest T2D risk observed among individuals with LDL-C levels below 84 mg/dL and the lowest risk among those with LDL-C > 131 mg/dL, potentially reflecting the influence of genetic variants.

The genes that are associated both with lower LDL-C levels and higher risk of T2D have an effect on LDL-C level by distinct pathways including cholesterol absorption (NPC1L1) (16), endogenous cholesterol synthesis (HMGCR) [19, 20] and internalization of cholesterol-rich particles into the cell (PCSK9) [21, 22]. Alleles that lower LDL-C at HMGCR are associated with higher levels of fasting insulin and BMI, suggesting an insulin resistance-related mechanism predisposing to T2D development [3].

Although statin therapy has been shown to influence the incidence of T2D [23], as also confirmed in the present study, we show that its effect on increasing T2D risk was significant only in the group with LDL-C ≥ 131 mg/dL. The mechanisms underlying this phenomenon remain unclear; however, genetic studies have demonstrated that HMGCR variants are associated with alterations in both LDL cholesterol levels and T2D risk, suggesting a role for cellular cholesterol metabolism [3, 17, 24]. Moreover, while ezetimibe, PCSK9 inhibitors and bempedoic acid mediate their LDL-lowering effect via upregulating LDL receptor activity, HMGCR inhibition by statins primarily increases LDL receptor expression [25] which might be a proxy for the relationship between HMGCR activity and T2D development—underscoring a relationship between intracellular cholesterol and T2D risk. Several findings support the hypothesis that the common pathway in familial hypercholesterolemia and statin therapy—cellular cholesterol uptake—plays a role in the development of T2D, perhaps because increased intracellular cholesterol levels are detrimental for pancreatic beta cell function. The addition of LDL cholesterol to the cultured medium of isolated rat islet beta cells resulted in cell death, and this phenomenon was LDL receptor dependent [26, 27]. Furthermore, a decreased glucose-stimulated insulin secretion has been observed in murine pancreatic islets incubated with LDL cholesterol, and this response was abolished in LDL receptor knockout animals [28]; the incubation of islets derived from pancreas donors with LDL cholesterol was detrimental as well [28]. Further support for this mechanism comes from investigations examining ABCA1, a key transmembrane protein that promotes cellular cholesterol efflux [29]. A study led by Michael Hayden demonstrated that pancreas-specific ABCA1 knockout mice exhibited increased plasma glucose levels and impaired insulin secretion [30]. The relationship between intracellular cholesterol concentration and pancreatic beta cell function was strengthened by the finding that miR-22 inhibition, causing increased ABCA1 expression, improved beta cell function [31]. Consistent with these findings, an altered intracellular cholesterol homeostasis by ABCA1 defects results in impaired insulin secretion in humans [32].

On the other hand, cholesterol is a key component of lipid rafts, being responsible for cell membrane function, and insulin receptor activity has been shown to be modulated by changes in plasma membrane lipid composition with a reduction in cells glucose uptake after removal of raft-promoting cholesterol from cells [33, 34].

Although various biological pathways have been proposed to explain the statin-induced increased risk for T2D [23, 35, 36], and despite the precise mechanism is still unclear, a pivotal role of LDL receptor may be suggested and this phenomenon may be supported by the findings of the present study.

Nonetheless, the lack of significant interaction of statin therapy on incident T2D for low LDL-C levels groups in the present study may imply that the reduction in plasma LDL-C concentration is accompanied by an increase in incident T2D largely independent on statin therapy. Additional support for this hypothesis comes from evidence that genetic variants in PCSK9 are linked to T2D, whereas intervention studies have not demonstrated such an association [5, 37,38,39,40], possibly because the impact of drug-induced LDL lowering on T2D risk becomes less evident at very low LDL levels.

The present study is not exempt from limitations. We acknowledge that the findings do not provide insight into the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms linking low LDL-C levels with an increased risk of incident T2D. One of the main limitations is the lack of data on statin potency and dosage at baseline; considering that the diabetogenic effect of statins is dose-dependent, we cannot exclude that the higher incidence of T2D in the group with LDL-C > 131 mg/dl may be due to the use of high-potency or high-dose statins. However, the magnitude of the difference between the risk of this group and those of the remaining three groups makes this hypothesis unlikely. Genetic analysis was not included in the assessment; nonetheless, the present study aims to describe the phenomenon in a general population in order to facilitate the choice of cholesterol-lowering therapy based on simple clinical characteristics. In addition, information on changes in lifestyle behaviors, such as physical activity and dietary patterns, which may have influenced T2D risk, was not available. Furthermore, the proportion of missing data for key variables including BMI, fasting plasma glucose, creatinine, and cholesterol was too high to permit reliable imputation, thereby reducing the sample size available for adjusted statistical models.

Nevertheless, a key strength of the study lies in the use of data from the general population, which helps to mitigate potential biases related to underdiagnosis of disease. This approach also addresses limitations commonly encountered in clinical trials, where post-randomization plasma glucose measurements may be less frequently available among participants without a prior diabetes diagnosis.

Conclusions

Our findings show that lower plasma LDL-C concentrations are inversely associated with the risk of developing type T2D in the general population. Notably, the higher incidence of T2D observed at lower LDL-C levels occurs in a manner largely independent of statin treatment.

Data availability

Once the datasets have been fully de-identified and all the main findings have been published, data collected for this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the last author for research purposes, with a signed data access agreement.

References

Sattar N, Preiss D, Murray HM, Welsh P, Buckley BM, de Craen AJ, et al. Statins and risk of incident diabetes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomised statin trials. Lancet. 2010;375(9716):735–42.

Collaboration CTT. Electronic address cnoau, Cholesterol Treatment Trialists C: Effects of statin therapy on diagnoses of new-onset diabetes and worsening glycaemia in large-scale randomised blinded statin trials: an individual participant data meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2024;12(5):306–19.

Swerdlow DI, Preiss D, Kuchenbaecker KB, Holmes MV, Engmann JE, Shah T, et al. HMG-coenzyme A reductase inhibition, type 2 diabetes, and bodyweight: evidence from genetic analysis and randomised trials. Lancet. 2015;385(9965):351–61.

Besseling J, Kastelein JJ, Defesche JC, Hutten BA, Hovingh GK. Association between familial hypercholesterolemia and prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA. 2015;313(10):1029–36.

Schmidt AF, Swerdlow DI, Holmes MV, Patel RS, Fairhurst-Hunter Z, Lyall DM, et al. PCSK9 genetic variants and risk of type 2 diabetes: a mendelian randomisation study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017;5(2):97–105.

Ference BA, Robinson JG, Brook RD, Catapano AL, Chapman MJ, Neff DR, et al. Variation in PCSK9 and HMGCR and risk of cardiovascular disease and diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(22):2144–53.

Klimentidis YC, Arora A, Newell M, Zhou J, Ordovas JM, Renquist BJ, et al. Phenotypic and genetic characterization of lower LDL cholesterol and increased type 2 diabetes risk in the UK biobank. Diabetes. 2020;69(10):2194–205.

Ravi A, Koyama S, Cho SMJ, Haidermota S, Hornsby W, Ellinor PT, et al. Genetic predisposition to low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and incident type 2 diabetes. JAMA Cardiol. 2025;10(4):379–83.

Song B, Sun L, Qin X, Fei J, Yu Q, Chang X, et al. Associations of lipid-lowering drugs with blood pressure and fasting glucose: a Mendelian Randomization Study. Hypertension. 2025;82(4):743–51.

Trimarco V, Izzo R, Jankauskas SS, Fordellone M, Signoriello G, Manzi MV, et al. A six-year study in a real-world population reveals an increased incidence of dyslipidemia during COVID-19. J Clin Invest. 2024. https://doi.org/10.1172/JCI183777.

Trimarco V, Izzo R, Pacella D, Manzi MV, Jankauskas SS, Gallo P, et al. Aspirin reduces the risk of type 2 diabetes associated with COVID-19. NPJ Metab Health Dis. 2025;3(1):27.

Russo V, Piccinocchi G, Mandaliti V, Annunziata S, Cimmino G, Attena E, et al. Cardiovascular comorbidities and pharmacological treatments of COVID-19 patients not requiring hospitalization. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010102.

Ullah H, Esposito C, Piccinocchi R, De Lellis LF, Santarcangelo C, Minno AD, et al. Postprandial glycemic and insulinemic response by a brewer’s spent grain extract-based food supplement in subjects with slightly impaired glucose tolerance: a monocentric, randomized, cross-over, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Nutrients. 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14193916.

Izzo R, Pacella D, Trimarco V, Manzi MV, Lombardi A, Piccinocchi R, et al. Incidence of type 2 diabetes before and during the COVID-19 pandemic in Naples, Italy: a longitudinal cohort study. EClinicalMedicine. 2023;66:102345.

Egan AM, Wood-Wentz CM, Mohan S, Bailey KR, Vella A. Baseline fasting glucose level, age, sex, and body mass indexand the development of diabetes in US adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2025;8(1):e2456067. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.56067.

Trimarco V, Izzo R, Gallo P, Manzi MV, Forzano I, Pacella D, et al. Long-lasting control of LDL cholesterol induces a 40% reduction in the incidence of cardiovascular events: new insights from a 7-year study. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2024;388(3):742–7.

Lotta LA, Sharp SJ, Burgess S, Perry JRB, Stewart ID, Willems SM, et al. Association between low-density lipoprotein cholesterol-lowering genetic variants and risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(13):1383–91.

Liu DJ, Peloso GM, Yu H, Butterworth AS, Wang X, Mahajan A, et al. Exome-wide association study of plasma lipids in >300,000 individuals. Nat Genet. 2017;49(12):1758–66.

Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Multivalent feedback regulation of HMG CoA reductase, a control mechanism coordinating isoprenoid synthesis and cell growth. J Lipid Res. 1980;21(5):505–17.

Burkhardt R, Kenny EE, Lowe JK, Birkeland A, Josowitz R, Noel M, et al. Common SNPs in HMGCR in micronesians and whites associated with LDL-cholesterol levels affect alternative splicing of exon13. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(11):2078–84.

Benjannet S, Rhainds D, Essalmani R, Mayne J, Wickham L, Jin W, et al. NARC-1/PCSK9 and its natural mutants: zymogen cleavage and effects on the low density lipoprotein (LDL) receptor and LDL cholesterol. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(47):48865–75.

Maxwell KN, Breslow JL. Adenoviral-mediated expression of Pcsk9 in mice results in a low-density lipoprotein receptor knockout phenotype. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(18):7100–5.

Galicia-Garcia U, Jebari S, Larrea-Sebal A, Uribe KB, Siddiqi H, Ostolaza H, et al. Statin treatment-induced development of type 2 diabetes: from clinical evidence to mechanistic insights. Int J Mol Sci. 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21134725.

Zhang YY, Chen BX, Wan Q. Association of lipid-lowering drugs with the risk of type 2 diabetes and its complications: a mendelian randomized study. Diabetol Metab Syndr. 2024;16(1):240.

Santulli G, Kansakar U, Jankauskas SS, Varzideh F: Comparative LDL-C Lowering Efficacy of Non-Statin Therapies: Inclisiran is Better than Ezetimibe, PCSK9 inhibitors, and Bempedoic Acid. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 2025.

Roehrich ME, Mooser V, Lenain V, Herz J, Nimpf J, Azhar S, et al. Insulin-secreting beta-cell dysfunction induced by human lipoproteins. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(20):18368–75.

Cnop M, Hannaert JC, Grupping AY, Pipeleers DG. Low density lipoprotein can cause death of islet beta-cells by its cellular uptake and oxidative modification. Endocrinology. 2002;143(9):3449–53.

Rutti S, Ehses JA, Sibler RA, Prazak R, Rohrer L, Georgopoulos S, et al. Low- and high-density lipoproteins modulate function, apoptosis, and proliferation of primary human and murine pancreatic beta-cells. Endocrinology. 2009;150(10):4521–30.

Oram JF, Lawn RM. ABCA1. The gatekeeper for eliminating excess tissue cholesterol. J Lipid Res. 2001;42(8):1173–9.

Brunham LR, Kruit JK, Pape TD, Timmins JM, Reuwer AQ, Vasanji Z, et al. Beta-cell ABCA1 influences insulin secretion, glucose homeostasis and response to thiazolidinedione treatment. Nat Med. 2007;13(3):340–7.

Wijesekara N, Zhang LH, Kang MH, Abraham T, Bhattacharjee A, Warnock GL, et al. Mir-33a modulates ABCA1 expression, cholesterol accumulation, and insulin secretion in pancreatic islets. Diabetes. 2012;61(3):653–8.

Vergeer M, Brunham LR, Koetsveld J, Kruit JK, Verchere CB, Kastelein JJ, et al. Carriers of loss-of-function mutations in ABCA1 display pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(4):869–74.

Suresh P, Miller WT, London E. Phospholipid exchange shows insulin receptor activity is supported by both the propensity to form wide bilayers and ordered raft domains. J Biol Chem. 2021;297(3):101010.

Warda M, Tekin S, Gamal M, Khafaga N, Celebi F, Tarantino G. Lipid rafts: novel therapeutic targets for metabolic, neurodegenerative, oncological, and cardiovascular diseases. Lipids Health Dis. 2025;24(1):147.

Axsom K, Berger JS, Schwartzbard AZ. Statins and diabetes: the good, the bad, and the unknown. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2013;15(2):299.

Sattar N, Taskinen MR. Statins are diabetogenic–myth or reality? Atheroscler Suppl. 2012;13(1):1–10.

Lu J, Liu Y, Wang Z, Zhou K, Pan Y, Zhong S, et al. Genetic associations of lipids and lipid-modifying drug targets with type 2 diabetes in the Chinese population. JACC Asia. 2024;4(11):825–38.

Fischer LT, Hochfellner DA, Knoll L, Pottler T, Mader JK, Aberer F. Real-world data on metabolic effects of PCSK9 inhibitors in a tertiary care center in patients with and without diabetes mellitus. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2021;20(1):89.

Marouf BH, Iqbal Z, Mohamad JB, Bashir B, Schofield J, Syed A, et al. Efficacy and safety of PCSK9 monoclonal antibodies in patients with diabetes. Clin Ther. 2022;44(2):331–48.

Morelli MB, Wang X, Santulli G. Functional role of gut microbiota and PCSK9 in the pathogenesis of diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. Atherosclerosis. 2019;289:176–8.

Acknowledgements

-

Funding

The Santulli Lab is supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (NIH): National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK: R01-DK123259, R01-DK033823), National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI: R01-HL164772, R01-HL159062, R01-HL146691, T32-HL144456), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS: UL1-TR002556-06, UM1-TR004400) to G.S., by the American Heart Association (AHA: 24IPA1268813), and by the Monique Weill-Caulier and Irma T. Hirschl Trusts (to G.S.). RI is supported by the European Union—NextGenerationEU—NRRP M6C2—Investment 2.1 Enhancement and strengthening of biomedical research in the NHS. The work was supported by PNRR-POC-2022–12376833 (CAREMODE Project: New multimodal CArdioREspiratory MOnitoring DEvice to improve chronic patient management), financed by the European Union EU (EU), NextGenerationEU—CUP: C63C22001310007 to R.I.

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Board at the “ASL Napoli 1 Centro” reviewed and approved this study organized with the patronage of the Italian Society for Cardiovascular Prevention (SIPREC) and granted a waiver of informed consent (Protocol# 257/22–23). The investigation conforms to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lembo, M., Trimarco, V., Pacella, D. et al. A six-year longitudinal study identifies a statin-independent association between low LDL-cholesterol and risk of type 2 diabetes. Cardiovasc Diabetol 24, 429 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-025-02964-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12933-025-02964-6