Introduction

Over the past few decades, policymakers have developed and implemented an expanding array of policies, policy instruments, and policing strategies to address crime and disorder (Welsh et al. 2024). From targeted approaches such as hot spot policing (Weisburd et al. 2024) and disorder policing (Braga et al. 2024) to advances in surveillance technology (e.g., CCTVs) (Piza 2024), community-based interventions (Koehler and Lösel 2025), and improved urban planning initiatives (Armitage and Tompson 2022), cities have implemented diverse tactics to improve public safety and reduce citizens’ perceived insecurity (Nazzari et al. 2025). Among these efforts, curfew laws have seen renewed interest in the United States as a regulatory policy instrument to deter crime. While often associated with youth restrictions, curfew laws also include: (a) emergency curfews; and (b) business curfews. Emergency curfews are enacted in response to crises such as natural disasters or public health emergencies, while business curfew laws are designed to restrict the operating hours of specific establishments that are believed to contribute—intentionally or unintentionally—to crime, loitering, and public disturbances.

Unlike broad citywide policies, business curfews are typically localized, targeting high-crime areas with tailored restrictions. In the United States, the authority to impose such curfews typically rests with state and local governments, and in some instances, law enforcement agencies; through state statutes or local ordinances, authorities may establish time frames during which businesses must cease operations and individuals are prohibited from loitering in public spaces. Most such measures are temporary, activated in direct response to documented increases in criminal activity or emerging public safety threats. In recent years, several major U.S. cities, including New York, San Francisco, Miami, Philadelphia, Columbus, Dallas, and West Haven, have adopted business curfews to address neighborhood-level crime and disorder.

From a public policy analysis perspective, curfews can be understood as a form of command-and-control regulation—a direct restriction on private-sector activity for the purpose of public safety and urban security (Hood et al. 2007). Unlike incentive-based or informational strategies commonly used in local governance (Edwards and Hughes 2012), such measures impose visible and coercive constraints. While potentially effective in reducing crime opportunities, they also raise enduring questions of effectiveness, proportionality, and distributional equity (Persak 2018). Beyond these design concerns, curfews may carry broader normative implications by restricting fundamental freedoms of movement and association, disproportionately affecting marginalized populations, and generating tensions around fairness, social justice, and legitimacy (Crocitti and Selmini 2017). As governments seek pragmatic tools for reducing crime while preserving economic vitality, understanding both the empirical effects and the wider unintended consequences of curfews becomes a pressing concern.

The theoretical rationale behind business curfews can be understood through the lens of situational crime prevention (SCP), which emphasizes reducing opportunities for crime by altering the immediate environment. SCP achieves this through five primary mechanisms: (1) increasing the effort required to commit a crime, (2) increasing the immediate risks of detection, (3) reducing the rewards of offending, (4) removing excuses for offending, and (5) reducing temptations and provocations (see, for a review, Clarke 2018). By restricting late-night activity in crime-prone areas, curfews narrow the temporal and spatial windows during which criminal activities can occur, limiting the locations where potential offenders can congregate and making illicit behaviors more difficult to execute (Felson and Cohen 2017). Curfews also reshape the routines of individuals who rely on late-night businesses for cover, compelling them to adjust or abandon offending strategies (Wilcox and Cullen 2018). By establishing predictable closing hours, curfews enhance guardianship and reconfigure activity spaces, reflecting SCP’s broader goal of designing environments that reduce criminal opportunities (see, for a review, Laycock 2023).

Nonetheless, alternative theoretical perspectives highlight potential unintended consequences. The well-established “eyes on the street” concept in urban studies posits that the routine presence of people—whether as passive observers or active participants—enhances informal surveillance and helps deter crime (see, for a review, Linning and Eck 2021). This effect is particularly pronounced when business owners are integrated into the social fabric of the neighborhood. From a place management perspective, business and property owners play a pivotal role in regulating behavior and preventing crime on their premises—often more effectively than nearby residents (Linning et al. 2022; Eck and Clarke 2019). Consequently, closing businesses could inadvertently remove these key guardians, potentially increasing opportunities for illicit activity rather than reducing them.

Despite these competing theoretical perspectives, empirical research on the impact of business curfews as a regulatory policy instrument on crime remains limited. Most scholarly attention has focused on the effects of other types of curfew laws, particularly juvenile curfews (see, for a review, Wilson et al. 2016). Existing empirical insights into the effects of business closures on crime primarily come from emergency-driven restrictions, such as those imposed during the COVID-19 pandemic (Ekman and Jakobsson 2024; Gerell et al. 2022), or the closure of marijuana dispensaries due to policy changes (Chang and Jacobson 2017). While these instances involve temporary business shutdowns, they were not explicitly designed to curb crime, making their findings only partially applicable. As a result, the direct impact of business curfews as a deliberate crime prevention measure remains an open question, highlighting a significant gap in the literature.

To the best of our knowledge, no study has empirically evaluated the effectiveness of policies and policy instruments that restrict business operations as a means of reducing crime. Generating robust empirical evidence on this issue is essential, particularly as debates over the fairness and impact of such measures continue. Business owners contend that these policies and instruments unfairly target their establishments, jeopardizing local economic vitality and employment opportunities, while holding them responsible for criminal behaviors beyond their control. Concurrently, some community members raise concerns that curfews may infringe upon fundamental rights, such as the right to assemble. Growing legislative efforts to ban business curfews further underscore the need for evidence-based policymaking and balanced regulatory approaches.Footnote 1

The present study aims at addressing this knowledge gap by answering the following research question: How effective are business curfews in reducing crime? To investigate this, it quantitatively evaluates the impact of a recent business curfew, enforced between 12:00 a.m. and 5:00 a.m., on selected businesses in the Tenderloin neighborhood of San Francisco, California, using a custom Bayesian Structural Time Series (BSTS) model. Effective from July 27, 2024, the curfew was specifically implemented to reduce drug activity in the neighborhood.

The program requires a progress report to be delivered to San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors six months after its launch. In April 2025, San Francisco Police Department (SFPD) Commander Derrick Lew, in testimony before the Board of Supervisors’ Public Safety and Neighborhood Services Committee, described the curfew as successful during its first nine months, stating: “My recommendation would be to absolutely keep it going.” Commander Lew cited reductions in street loitering and crime as evidence of the program’s effectiveness. However, this assertion was based on basic pre-post observations, lacking rigorous empirical evaluation and failing to account for the non-random nature of the policy’s implementation.Footnote 2

Our study contributes to public policy analysis and criminology by offering one of the first quasi-experimental assessments of a business curfew, using a BSTS model tailored to high-risk urban micro-areas. Our results provide not only preliminary evidence of effectiveness, but also a framework for assessing similar interventions under real-world constraints of policy design, data availability, and implementation complexity.

The article is structured as follows. The next section reviews existing empirical evidence on business closures and their impact on crime. The “Analytical Framework” section outlines the case study, data, and methodology employed in this study. The “Results” section presents the key findings from the analysis. The final section discusses the results, along with the methodological limitations, policy implications, and recommendations for future research.

Literature review

Criminologists and social scientists have long studied the relationship between crime and place (see, for a review, Tucker and O’Brien 2024). A key finding across this body of research is that crime is not randomly distributed in space; rather, it tends to cluster within small, well-defined geographic areas (Weisburd et al. 2024). Within this broader pattern, research has focused on how land use influences crime patterns. Numerous studies have consistently found that non-residential land use, particularly commercial facilities, is associated with higher crime levels (Askey et al. 2018; Lee and Eck 2019). In particular, specific facilities like bars, pawn shops, corner stores and check-cashing businesses have been identified as criminogenic, generating significantly higher crime rates compared to other types of businesses (Groff 2014; Wilcox and Eck 2011).

However, research also shows that the criminogenic effects of these “micro-places” depend heavily on their broader neighborhood context. Facilities that may serve as crime generators in one area may not have the same impact elsewhere. Their effects are more pronounced in neighborhoods with high concentrations of potential offenders, weak collective efficacy, and limited guardianship, and are often mitigated in more stable, closely monitored areas (Boessen and Hipp 2018; Wilcox and Tillyer 2017).

These contextual effects have important implications for place-based crime prevention and urban regulation (Boessen and Hipp 2018). Reflecting this, scholars have increasingly highlighted how local authorities use targeted regulatory policy instruments—such as curfews, business restrictions, and exclusion zones—to manage perceived disorder and crime, especially in high-density urban areas. These interventions exemplify a broader trend toward what researchers have described as spatialized urban security governance (Beckett and Herbert 2010).

This perspective is further reinforced by research showing that business owners can exert guardianship over crime, influencing crime patterns across places (Linning et al. 2022; Tucker and O’Brien 2024). For example, studies have found empirical support for the crime-reduction effects of Business Improvement District initiatives, which require business owners to take on active place management roles, involving responsibilities such as overseeing the area, implementing security measures, and coordinating promotional strategies (see, for a review, Moir et al. 2024). Conversely, closing or restricting access to specific businesses—even temporarily—can sometimes produce unintended consequences, including increases in crime (see, for example, McCannon et al. 2022).

Despite these well-established theoretical and empirical connections, limited attention has been paid to interventions specifically targeting commercial operations as a means of crime prevention. Business curfews, as a form of command-and-control regulation (Hood et al. 2007), represent a direct and visible method of restricting private activity for public ends. These policy instruments are often enacted in response to political pressures and implemented with limited evidence on effectiveness or other implications. Unlike traditional hot-spot policing or situational crime prevention strategies, business curfews do not directly alter the physical environment but instead aim to influence the temporal dynamics of crime by limiting the availability of criminogenic spaces during high-risk periods.

Yet, no empirical research has investigated the substantive dimension of these interventions, particularly in terms of their policy outcomes and impacts, which are typically assessed through systematic impact evaluation (Howlett et al. 2009)Footnote 3. Existing evidence on similar policies and instruments is sparse and often indirect. Research on juvenile curfews, for example, has yielded mixed results regarding their effectiveness in reducing crime (see, for a review, Wilson et al. 2016). Likewise, studies examining the effects of temporary business closures—such as business restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic (Gerell et al. 2022; Ekman and Jakobsson 2024) or policy-driven closures of marijuana dispensaries (Chang and Jacobson 2017)—offer relevant insights but were not designed primarily as crime prevention measures. While these interventions share similarities with business curfews, their distinct objectives and contexts highlight the need for direct empirical research on the crime-reduction potential of commercial curfews.

This study addresses a critical gap by rigorously evaluating whether, and to what extent, business curfews reduce crime. In doing so, it advances our understanding of the causal link between commercial activity and crime patterns and offers a basis for assessing how temporal restrictions on businesses may influence public safety. Beyond its empirical contribution, the study provides actionable evidence for policymakers weighing the benefits of curfews against potential economic and social costs—helping inform the design and targeting of regulatory interventions in high-risk urban areas.

Analytical framework

Case study

The Tenderloin is a high-crime neighborhood located in downtown San Francisco, California. As part of a long-lasting effort to combat drug-related crime and improve public safety in the area, the San Francisco Board of Supervisors unanimously approved the “Tenderloin Retail Hours Restriction Pilot Program” on June 25, 2024. Proposed by former Mayor London Breed, the two-year initiative was enacted on June 27, 2024, with implementation beginning one month later.Footnote 4

Beginning July 27, 2024, retail stores within the designated 20-block “Tenderloin Public Safety Area” that sell pre-packaged food, tobacco products, or tobacco-related devices were prohibited from operating between 12:00 a.m. and 5:00 a.m.Footnote 5 The targeted zone, identified as a high-crime area, is bounded by O’Farrell and McAllister Streets (north and south) and Polk and Jones Streets (west and east).Footnote 6 Notably, the program exempts bars, restaurants, and non-retail businesses from these restrictions, focusing specifically on convenience stores and similar retail establishments that have been identified as hotspots for drug-related activity. Although the scope of the restriction is clearly defined, affected businesses cannot be reliably identified in existing registration data using available codes (e.g., NAICS, LIC), and no official figures or credible estimates are available.

Stores that violate the ordinance will face an administrative citation of up to $1,000 for each hour of noncompliance, with a warning issued for the first hour of violation. There is no cap on the total number of fines that can be imposed. Repeat offenders may also face legal action from the City Attorney, who can seek a court order to enforce compliance and recover unpaid fines.

This program was prompted by police observations of disproportionately high rates of drug-related crime occurring between 12:00 a.m. and 5:00 a.m. in the area. In particular, law enforcement has documented that “large groups of people engaged in illicit drug sales and use congregate close to open food markets and tobacco establishments in the late night and early morning” (San Francisco Board of Supervisors 2024, 2). Law enforcement identified these dense gatherings as a key challenge, as they hinder the ability to establish reasonable suspicion or probable cause. Officers are often outnumbered, raising safety concerns and limiting their ability to intervene effectively. Open businesses further complicate enforcement by offering refuge to individuals involved in illegal activity, allowing them to evade detection when police arrive.Footnote 7

Data

To conduct the analysis, we drew upon the San Francisco’s Open Data Portal.Footnote 8 Specifically, we used data on all police incidents reported by the SFPD between January 2018 and April 2025. The dataset compiles data from the department’s Crime Data Warehouse to provide information on incident reports filed by the SFPD’s police officers or self-reported by members of the public using SFPD’s online reporting system. The dataset includes information on the type, date, time and location of incidents. For privacy purposes, the dataset does not include any identifiable information of any person (e.g., suspect, victim, reporting party, officer, witness).

Incident reports are added to open data once they have been reviewed and approved by a supervising Sergeant or Lieutenant. The incident reports are categorized into the following categories based on how the report was received and the type of incident: (a) Initial reports: the first report filed for an incident; (b) Coplogic reports: incident reports filed by members of the public using SFPD’s online reporting system; (c) Vehicle reports: any incident reports related to stolen and/or recovered vehicles; (d) Supplemental reports: a follow-up report to an initial, coplogic or vehicle report. To ensure accuracy and avoid double-counting, we excluded supplemental reports from our analysis. We also filtered incidents to remove duplicated incident IDs and focus on unique incidents. For example, a single drug-related incident may result in multiple entries in the database. If an individual is found in possession of various drugs for sale, such as opiates, methamphetamine, and cocaine, three separate incident reports will be created. However, all these reports stem from the same underlying incident, which is the primary focus of our analysis.

We selected two crime categories from the Police Incident database: (a) Drug Offense and (b) Drug Violation. Specifically, Drug Offense covers a wide range of illegal activities, including but not limited to: possession for personal use, possession for sale, transportation of controlled substances, loitering in areas where narcotics are sold or consumed, being under the influence of a controlled substance, and possession of narcotics paraphernalia. Drug Violation, on the other hand, refers to incidents where an individual is found to be armed while in possession of a controlled substance.

To conduct the analysis, crime incidents specific to the Tenderloin were extracted from the broader city dataset. Only incidents mapped within the Tenderloin Public Safety Area were included for detailed examination. To protect privacy, the SFPD anonymizes crime incident data by mapping locations to the nearest intersections. As a result, our analysis relied on the longitude and latitude coordinates provided in the SFPD dataset to accurately identify incidents within the designated area. When defining the boundaries of the treated area, we ensured that both sides of the boundary streets were included, as explicitly outlined in the ordinance. This approach provided a comprehensive and precise representation of the treated area, minimizing the risk of excluding relevant crime incidents.

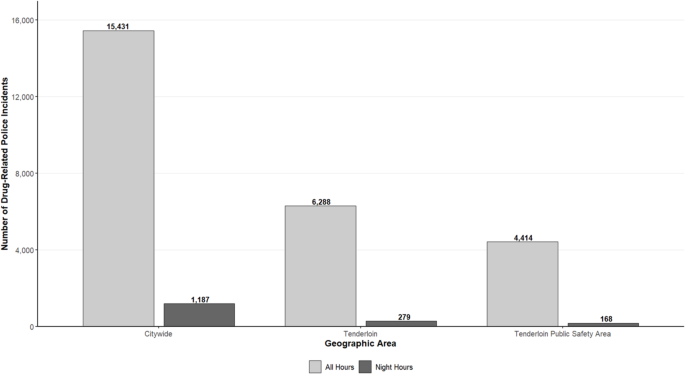

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of drug-related crime incidents, comparing data across the entire city of San Francisco, the Tenderloin neighborhood, and the Tenderloin Public Safety Area. The data spans from January 2018 to April 2025 and includes both total daily incidents and those occurring specifically between 12:00 a.m. and 5:00 a.m. This visualization provides a clearer view of temporal and spatial crime patterns, highlighting the disproportionate concentration of late-night incidents in the area directly targeted by the policy intervention.

Distribution of Drug-Related Police Incidents in San Francisco by Location and Time Period, January 2018 – April 2025.

Note: Bars show total drug-related police incidents aggregated over the study period. Light gray bars represent incidents at all hours; dark gray bars represent incidents between 12:00 a.m. and 5:00 a.m. The Tenderloin Public Safety Area is a 20-block zone within the broader Tenderloin neighborhood

The Tenderloin may cover only a fraction of San Francisco, but when it comes to drug-related incidents, it dominates the map. It accounts for 41% of all drug-related incidents, with nearly 69% of those concentrated in the 20-block area designated as the Tenderloin Public Safety Area. This pattern persists after dark: between 12:00 a.m. and 5:00 a.m., the Tenderloin accounts for approximately 24% of all drug-related incidents in the city, with the Public Safety Area alone representing 14% of the citywide total during these late-night hours.

Given the low occurrence rate and sparse distribution of incidents after applying temporal and spatial filters related to the policy intervention (only 168 occurrences over seven years), we aggregated daily data at a monthly level to enhance statistical power and ensure more robust parameter estimates. This aggregation is further justified by the intervention’s medium-term rather than immediate effects. Using daily or weekly data could introduce excessive noise, making it difficult to identify meaningful variations in crime trends. To ensure comparability across months, we standardized the data by calculating monthly incident rates (total incidents divided by days per month).

Despite crime reduction being just one of four main objectives of the program, data availability constraints necessitate focusing our analysis exclusively on this outcomeFootnote 9. We address the implications of this limitation and propose directions for future research in the “Discussion and Conclusions” section.

Methodology

A key challenge in evaluating policy interventions is estimating the counterfactual—what would have happened in the absence of the policy. Standard approaches, such as the synthetic control method (Abadie et al. 2010) typically rely on constructing comparison groups from similar units (e.g., neighborhoods or districts) that share observable characteristics and pre-intervention trends. However, this strategy breaks down when the treated unit is highly specific or idiosyncratic.

In our case, the intervention targeted a particularly small and unique area: the Tenderloin Public Safety Area, a roughly 20-block zone within San Francisco’s Tenderloin neighborhood. This level of spatial granularity creates serious barriers to finding comparable control units. Other neighborhoods in San Francisco either do not share the same intensity of drug-related crime, demographic composition, urban density, or history of concentrated law enforcement—and sub-neighborhood level crime data is often unavailable or inconsistent.

Moreover, the broader city context complicates matters further: San Francisco experienced a citywide decline in crime during the study period, likely influenced by macro-level economic, social, and policy shiftsFootnote 10. These background trends make it even harder to attribute observed changes in the treated area to the curfew alone when using external controls.

Given these limitations, we employ a BSTS model, which allows us to construct a counterfactual using only the treated unit’s own historical data (Brodersen et al. 2015). This approach is particularly well-suited to settings like ours, where traditional comparison groups are unavailable or unreliable due to spatial scale or contextual uniqueness. By modeling underlying trends, seasonal patterns, and structural changes using pre-intervention data, BSTS provides a data-driven estimate of the counterfactual post-policy trajectory—offering a more flexible and refined approach than traditional interrupted time series analysis (Gianacas et al. 2023).

Equally important is the more comprehensive handling of uncertainty offered by Bayesian methods, which provides a distinct advantage over traditional frequentist approaches—particularly in the fields of criminology and criminal justice where available data are often noisy and incomplete (Barnes et al. 2020). Reflecting these advantages, BSTS models have gained traction in criminological research in recent years. They have been widely applied to estimate the impact of specific public policies or other exogenous shocks on crime (Campedelli et al. 2021; Clark-Moorman et al. 2019; Dorsett 2021), as well as on broader crime-related outcomes such as police traffic stops, police turnover, and 911 calls volume (Boehme and Mourtgos 2024; Koziarski 2021; Sierra-Arévalo et al. 2023; Mourtgos et al. 2022; Richards et al. 2021).

BSTS models are best described using a state-space framework, comprising two key equations: (a) the observation equation, which links observed data with the latent state; and (b) the transition equation, which describes the evolution of the latent state over time. The observation equation is defined as:

$$\:{\text{y}}_{\text{t}}={\text{Z}}_{\text{t}}^{\text{T}}\:{a}_{t}+{{\upepsilon\:}}_{\text{t}}$$

where \(\:{\text{y}}_{\text{t}}\) is a scalar observation at time t, \(\:{\text{Z}}_{\text{t}}^{\text{T}}\) is the output vector, \(\:{a}_{t}\) is the unobserved latent state vector at time t, and \(\:{{\upepsilon\:}}_{\text{t}}\) is the observation error, assumed to follow a Gaussian distribution \(\:{\epsilon\:}_{t}\sim\:N(0,{\sigma\:}^{2})\). The transition equation is defined as:

$$\:{a}_{\text{t}+1}={\text{T}}_{\text{t}}{a}_{\text{t}}+{\text{R}}_{\text{t}}{{\upeta\:}}_{\text{t}}$$

where \(\:{a}_{\text{t}+1}\) is the unobserved latent state, \(\:{\text{T}}_{\text{t}}\) is the transition matrix, and \(\:{\text{R}}_{\text{t}}\) is the control matrix. \(\:{\text{R}}_{\text{t}}{{\upeta\:}}_{\text{t}}\) allows the inclusion of components such as seasonality, trends, and external covariates in the model. The error term (\(\:{{\upepsilon\:}}_{\text{t}}\) and \(\:{{\upeta\:}}_{\text{t}}\)) are Gaussian and independent.

Put simply, the latent state vector \(\:{a}_{t}\) represents the unobserved structural components of the time series—such as the underlying trend, recurring seasonal patterns, and the effects of explanatory variables. The observation equation maps these hidden components onto the observed data, illustrating how they combine to generate the time series at each time point. In parallel, the transition equation governs how the latent state evolves over time, capturing both systematic changes and random shocks. This dual-equation structure enables BSTS models to capture complex, real-world temporal dynamics while explicitly accounting for uncertainty and measurement errors.

The pre-intervention time series began in January 2018 and ended in July 2024. The post-period time series started in August 2024 and ended in April 2025. Accordingly, the pre-intervention series is 79 months in length, with a post-intervention span of 9 months, totaling 88 data points. To fully leverage the flexibility of these models, we estimated a custom BSTS model using both the “bsts” package (Scott and Varian 2014) and the “CausalImpact” package (Brodersen et al. 2015) in R.Footnote 11

Our custom BSTS model incorporates a studentized local linear trend, a harmonic trigonometric seasonal component, and an autoregressive structure. All model components employ default non-informative priors as recommended by the “bsts” package documentation: spike-and-slab priors for regression coefficients, inverse-gamma priors for innovation variances (df = 0.01), and decreasing inclusion probabilities for autoregressive lags. The local linear trend component is employed to model the long-term evolution of crime rates, accommodating gradual structural shifts over time. Given the high kurtosis observed in the outcome time series—indicating heavy tails or potential outliers—a studentized linear trend is a more suitable choice for modeling the long-term evolution of crime rates. Specifically, it incorporates a Student-t distribution to model the trend, which is specifically designed to mitigate the impact of outliers and produce more stable and reliable trend estimates.

Seasonal variations in crime data are modeled using a harmonic trigonometric function based on a Fourier series expansion. Specifically, the model incorporates three frequency components—annual (12-month), semi-annual (6-month), and quarterly (3-month) cycles—to capture the varying seasonal fluctuations in crime throughout the year. These frequencies allow the model to account for multiple temporal patterns, from the broader annual trends to shorter, more localized seasonal shifts. This specification ensures smooth transitions between adjacent periods, avoiding abrupt seasonal changes.

To account for short-term dependencies, we incorporate an autoregressive structure with a lag of six periods (AR(6)). This structure assumes that current crime levels are influenced by crime rates in the preceding six months, capturing delayed responses to policy changes, law enforcement efforts, and social dynamics. The AR component also helps minimize residual autocorrelation, ensuring that the model effectively accounts for persistent crime trends.

To ensure rigorous inference, we employ a Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) approach, drawing 20,000 posterior samples to estimate credible intervals. We construct 95% credible intervals for all posterior distributions, providing a robust measure of uncertainty and model reliability in estimating the impact of the policy under scrutiny.

Lastly, to more effectively isolate the causal effect of the regulatory policy instrument, we include a control variable to account for potential confounding. In the context of BSTS models, suitable predictors must correlate with the outcome of interest while remaining unaffected by the intervention itself. For this purpose, we include monthly average temperature in Fahrenheit registered at the San Francisco Downtown Station in the period of interest. These data were obtained from an open-access dataset provided by the National Centers for Environmental InformationFootnote 12. There is substantial empirical evidence linking temperature to variations in crime rates (see, for a review, Corcoran and Zahnow 2022), and temperature has been previously incorporated as a covariate in BSTS models of crime to help reduce noise and better capture underlying trend (see, for example, Campedelli et al. 2021). It is self-evident that temperature is exogenous to the policy intervention and thus satisfies the requirement of exogeneity, not being influenced by the treatment.

To assess the robustness of our results and address potential model dependence, we perform a sensitivity analysis using a Causal-ARIMA (Autoregressive Integrated Moving Average) model, proposed and developed by Menchetti et al. (2023). This alternative approach estimates the counterfactual effect of an intervention in observational settings where control units are not available by fitting an ARIMA model to the preintervention period to predict the series in the absence of intervention. Unlike BSTS, which models latent components in a Bayesian framework, Causal-ARIMA relies on a frequentist series decomposition and forecasting, offering a conceptually distinct method for counterfactual prediction.Footnote 13 This cross-model comparison helps verify the consistency of results and mitigate potential concerns about model dependence.

For both the BSTS and Causal-ARIMA models, we conduct formal diagnostic checks on the residuals to ensure model validity and reliability. Specifically, we examine Autocorrelation Function (ACF) and Partial Autocorrelation Function (PACF) plots to detect any residual autocorrelation and use Q-Q plots to assess the normality of the residuals. The absence of systematic patterns in these diagnostics indicates well-specified models. These evaluations strengthen the credibility of our counterfactual estimates and help ensure that the observed treatment effects are not artifacts of model misspecification.

Results

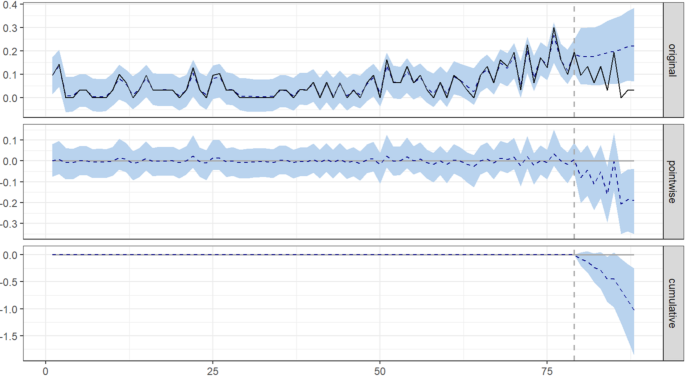

Figure 2 consists of three panels. The panel labeled “original” shows the observed data (solid black line) alongside the counterfactual prediction for the post-treatment period (horizontal blue dashed line), with a corresponding 95% credible interval shaded around it. The “pointwise” panel illustrates the pointwise causal effect estimated by the model, showing the difference between the observed data and the counterfactual predictions for each time point. The “cumulative” panel visualizes the cumulative effect of the intervention by summing the pointwise effects shown in the second panel. The dashed grey vertical line indicates the intervention date, which occurred in July 2024.

Effect of the Business Curfew Policy on Drug-Related Police Incidents in the Tenderloin Public Safety Area, January 2018 – April 2025.

Note: Estimates based on a customized BSTS model. The horizontal axis represents months from January 2018 to April 2025. Each monthly value is the rate of drug-related incidents per day (total incidents divided by the number of days in that month). The vertical dashed line indicates the implementation of the business curfew (July 2024)

The post-curfew period is associated with a decrease in drug-related crime in the Tenderloin Public Safety Area. Over the full nine-month observation window, the response variable had an average value of 0.08. In contrast, in the absence of the intervention, a counterfactual average value of 0.19 would have been expected. The difference between this counterfactual prediction and the observed response yields an estimate of the average causal effect of the intervention (−0.11), corresponding to a 56% relative decrease in drug-related crime (95% credible interval: −72% to −27%). This average effect over the post-intervention period can be considered statistically significant (Bayesian one-sided tail-area probability of p = 0.006).

Beyond the average effect, the intervention’s impact evolved over time. Pointwise comparisons—i.e., the difference between observed and counterfactual values at each time point—showed immediate reductions in crime following curfew application. However, these early reductions (August 2024 to January 2025) mostly fell within the model’s credible intervals, indicating effects that were detectable but not statistically significant. A notable exception occurred in December 2024, when observed values fell clearly below the lower bound of the credible interval. In contrast, during the final three months (February to April 2025), observed values consistently fell outside the credible intervals, indicating statistically significant reductions across multiple time points. This temporal pattern suggests that the full effect of the curfew emerged gradually—potentially driven by evolving enforcement strategies, increased public adherence, or broader behavioral adaptation.

To assess whether these reductions represent genuine crime prevention or merely spatial displacement, we applied the same BSTS model to two sets of comparison areas: (a) six neighborhoods directly bordering the Tenderloin; and (b) five randomly selected neighborhoods across San Francisco. The results provide strong evidence against the displacement hypothesis during the curfew hours themselves (Figure 3 in the Appendix). None of the bordering neighborhoods showed statistically significant increases in drug-related incidents between 12:00 a.m. and 5:00 a.m. (all p-values > 0.05). Similarly, the randomly selected control neighborhoods demonstrated negligible changes, indicating no systematic city-wide trends that could account for the observed effects. We then tested for potential temporal displacement effects, examining whether the intervention led to shifts in drug-related incidents to non-curfew hours. The analysis shows no evidence of temporal displacement in the Tenderloin area. The only significant deviation during non-curfew hours is observed in the South of Market neighborhood (Figure 4 in the Appendix), a pattern that should be investigated further in future evaluations.

The custom BSTS model exhibits reliable predictive validity. Comprehensive diagnostic evaluations (Figure 5 in the Appendix) confirm the robustness of the model. The autocorrelation function (ACF) and partial autocorrelation function (PACF) plots show no significant correlations at any lag, suggesting that the AR(6) component adequately accounts for temporal dependencies. The QQ plot further supports the assumption of residual normality, showing that the residuals closely follow the expected normal distribution. To substantiate these findings, formal statistical tests were conducted: the Shapiro-Wilk test for normality yielded a p-value of 0.306, indicating no significant departure from normality in the residuals, while the Ljung-Box test at lag 10 returned a p-value of 0.538, confirming the absence of significant autocorrelation. Collectively, these diagnostics support the model’s robustness and enhance confidence in the reliability of the estimated causal effects.

To assess the robustness of our findings, we conducted sensitivity analysis using a Causal-ARIMA framework (Table 1 in the Appendix). The Causal-ARIMA results provide additional insight into the distinction between immediate and cumulative effects. Our analysis reveals no immediate intervention effect, with the point causal effect estimated at −0.069 (SE = 0.07, p = 0.321). However, the intervention demonstrates clear long-term cumulative effectiveness, as captured by the cumulative causal effect of −0.556 (SE = 0.066, p < 0.001) and the temporal average causal effect of −0.062 (SE = 0.007, p < 0.001). This pattern suggests the intervention required time to manifest its full impact, with effects building progressively across the observation period. The consistency between Causal-ARIMA and BSTS methodologies provides compelling evidence for the intervention’s causal impact. Model diagnostics for the Causal-ARIMA specification (Figure 6 in the Appendix) confirm the adequacy of our approach, with residuals displaying no systematic patterns or deviations from normality assumptions.

Discussion and conclusions

This study systematically analyzes the Tenderloin Retail Hours Restriction Pilot Program, which was implemented to address drug-related crime by limiting access to retail establishments during nighttime hours in the Tenderloin Public Safety Area. In doing so, it contributes to the literature on urban crime control by providing one of the first rigorous impact evaluations of business curfews as a policy instrument. While curfews are increasingly adopted in high-crime areas of U.S. cities, they remain empirically understudied and theoretically under-integrated into broader frameworks of urban governance and policy design.

More broadly, the study speaks to the ways in which local authorities manage disorder through situational and regulatory instruments that restrict access to urban space, often in the name of public safety but with contested implications for equity, legitimacy, and economic vitality (Beckett and Herbert 2010). Within the public policy literature, this analysis contributes to discussions of policy instrument choice, particularly the use of command-and-control regulation as a fast-acting and politically visible means of intervention. It also speaks to implementation and design challenges, highlighting the need for evidence-informed policy responses in contexts where public pressure, spatial inequality, and institutional complexity collide.

The findings offer timely evidence that spatially and temporally targeted curfews can significantly reduce drug-related crime. Specifically, the analysis reveals a 56% reduction in drug-related incidents between 12:00 a.m. and 5:00 a.m. in the nine months following the curfew’s introduction. However, this effect did not appear uniformly over time. While crime rates were consistently lower than expected from the outset, statistically significant reductions only emerged several months into the intervention period. During the first six months (August 2024–January 2025), observed declines remained within margins of uncertainty, suggesting an early but inconclusive impact. It was only in the later period (February–April 2025) that observed incidents fell decisively below counterfactual projections.

This delayed effect may reflect gradual behavioral adaptation, changes in enforcement visibility, or shifts in local routines. The curfew likely constrained informal gathering places that often serve as hubs for covert exchanges, particularly in neighborhoods with high rates of housing insecurity and substance use. Removing access to these spaces may have disincentivized street-level dealing, especially among lower-level actors with limited flexibility and low risk tolerance.

The curfew may have also increased the perceived risk of detection. Reduced foot traffic and fewer open businesses may have made the environment appear more exposed and less predictable, diminishing the informal anonymity that often shields illicit activity. Additionally, the curfew may have prompted greater police or community presence—whether formal or informal—which can deter open-air drug activity, even without targeted enforcement.

Taken together, these mechanisms suggest that curfews can reshape the conditions under which street-level drug markets operate. However, their effectiveness may unfold gradually and require sustained implementation. At the same time, such benefits must be weighed against notable economic costs. The curfew imposed substantial constraints on local businesses—limiting hours, reducing revenue, and creating competitive disadvantages relative to businesses outside the restricted area. For smaller establishments, these pressures may have resulted in layoffs, permanent losses, or closures, threatening the neighborhood’s economic stability.

Therefore, any evaluation of the policy instrument must, at a minimum, balance its public safety benefits against its economic burdens. Future assessments should consider whether alternative approaches—such as targeted outreach, business subsidies, or more flexible curfew schedules—could achieve similar crime-reduction outcomes with fewer trade-offs.

Limitations of the study and directions for future research

This study has three limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, drug-related police incidents are used as a proxy for open-air drug dealing in the Tenderloin. While our results demonstrate a significant reduction in these incidents, they may not fully capture the complete scope of illicit activity or other forms of drug-related behavior that occur beyond police detection. Additionally, our analysis focuses primarily on crime reduction, which represents only one dimension of the program’s broader objectives. A more comprehensive evaluation would examine additional goals such as enhancing community safety perceptions, improving public health outcomes, and mitigating environmental hazards. Integrating multiple data sources, including community surveys and health indicators, would provide a more complete assessment of the program’s overall effectiveness beyond its demonstrated impact on drug-related crime.

Second, data limitations prevented the inclusion of key socioeconomic covariates—such as unemployment, income, and housing instability—that are closely linked to drug use and open-air drug markets (see, for a review, Nagelhout et al. 2017). However, data at the required granularity—namely neighborhood and monthly levels within the Tenderloin—was unavailable. Future research would benefit from incorporating these economic covariates to better contextualize the relationship between socioeconomic conditions and drug-related incidents. Increased access to neighborhood-level economic data would offer a more nuanced understanding of the structural drivers of drug-related crime and enhance the robustness of policy impact evaluations.

Third, the external validity of the study remains limited. It has long been recognized that implementation processes and their outcomes are inherently context-dependent (see, for example, Maynard-Moody et al. 1990; Calaresu and Triventi 2022). Results from the Tenderloin—an area with a unique combination of high population density, visible homelessness, and open-air drug markets—may not be generalizable to other urban environments. Cities with different demographic profiles, enforcement approaches, or retail dynamics may experience very different outcomes under similar curfew policies. Comparative studies in diverse urban contexts would provide a more comprehensive understanding of the conditions under which business curfews are effective, especially given that the local-urban dimension can assume variable but decisive importance depending on the institutional and socio-political configuration in which it is embedded (Tebaldi and Calaresu 2015).

Furthermore, it is important to emphasize that this study represents an interim evaluation. The Tenderloin curfew pilot is ongoing, with a planned two-year duration. A progress report to local authorities was expected six months after implementation as part of the program, and our study provides timely empirical evidence to contribute to the ongoing policy debate. While our findings offer insight into early effects on drug-related crime, they should not be interpreted as the final assessment of the program’s effectiveness. Interim analyses like this one are valuable for informing ongoing policy decisions, but a comprehensive evaluation at the end of the pilot will be critical for understanding long-term outcomes, potential displacement effects (both spatial and temporal), and unintended consequences.

Despite its limitations, this study offers new empirical insight into a largely overlooked area of urban governance. While juvenile curfews have been widely studied, business curfews remain underexamined, even as cities increasingly adopt them in response to public safety concerns. Without rigorous evaluation, such policies risk being shaped by anecdote, ideology, or partisan expediency—often tied to immediate electoral pressures—rather than by evidence of long-term effectiveness. This dynamic not only undermines policy legitimacy, but also raises concerns about fairness, equity, and the protection of fundamental rights in urban governance. By documenting both the measurable impacts and limitations of the Tenderloin curfew, this study contributes to a more informed foundation for policymaking. Future research should move beyond simple outcome metrics to examine how, where, and for whom change occurs. This includes identifying spatial diffusion effects, population-specific outcomes, and the timing of policy impacts. Most importantly, the field must develop theoretical frameworks to explain why certain interventions succeed (Braga et al. 2024). Clarifying these mechanisms is essential for designing policies that address root causes, ensuring that crime prevention strategies are both effective and sustainable across diverse urban environments.

References

Abadie, Alberto, Alexis Diamond, and Jens Hainmueller. 2010. Synthetic control methods for comparative case studies: Estimating the effect of California’s tobacco control program. Journal of the American Statistical Association 105 (490): 493–505. https://doi.org/10.1198/jasa.2009.ap08746.

Armitage, Rachel. and Lisa Tompson. 2022. The role of crime prevention through environmental design (CPTED) in improving household security. In The Handbook of Security, edited by Martin Gill. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91735-7_42

Askey, Amber, Ralph Perenzin, Elizabeth Groff Taylor, and Aaron Fingerhut. 2018. Fast food restaurants and convenience stores: Using sales volume to explain crime patterns in Seattle. Crime & Delinquency 64(14):1836–1857. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128717714792

Barnes, J. C., Michael F. TenEyck, Travis C. Pratt, and Francis T. Cullen. 2020. How powerful is the evidence in criminology? On whether we should fear a coming crisis of confidence. Justice Quarterly 37(3):383–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2018.1495252

Beckett, Katherine, and Steve Herbert. 2010. Banished: The new social control in urban America. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195395174.001.0001

Boehme, Hunter M., Scott M. Mourtgos. 2024. The effect of formal De-policing on Police traffic stop behavior and crime: Early evidence from lapd’s policy to restrict discretionary traffic stops. Criminology & Public Policy 6:1745–9133. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12673

Boessen, Adam, and John R.. Hipp. 2018. Parks as crime inhibitors or generators: Examining parks and the role of their nearby context. Social Science Research 76: 186–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.08.008.

Braga, Anthony A., Cory Schnell, and Brandon C. Welsh. 2024. Disorder policing to reduce crime: An updated systematic review and Meta-analysis. Criminology & Public Policy 23(3):745–775. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12667

Brodersen, Kay H., Fabian Gallusser, Jim Koehler, Nicolas Remy, and Steven L. Scott. 2015. Inferring causal impact using bayesian structural Time-Series models. The Annals of Applied Statistics 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1214/14-AOAS788

Calaresu, Marco, and Moris Triventi. 2022. Understanding contextual heterogeneity in the outcomes of large-scale security policies: Evidence from Italy (2007–12). Crime, Law and Social Change 77 (5): 5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-021-10007-w.

Campedelli, Gian, Alberto Maria, and Aziani, Serena Favarin. 2021. Exploring the immediate effects of COVID-19 containment policies on crime: An empirical analysis of the Short-Term aftermath in Los Angeles. American Journal of Criminal Justice 46(5):704–727. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12103-020-09578-6

Chang, Tom Y., Mireille Jacobson. 2017. Going to pot? The impact of dispensary closures on crime. Journal of Urban Economics 100(July):120–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2017.04.001

Clark-Moorman, Kyleigh, Jason Rydberg, and F. McGarrell. Edmund. 2019. Impact evaluation of a Parolee-Based focused deterrence program on Community-Level violence. Criminal Justice Policy Review 30(9):1408–1430. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887403418812999

Clarke, Ronald V. 2018. The Theory and Practice of Situational Crime Prevention. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice, by Ronald V. Clarke. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264079.013.327

Corcoran, Jonathan, and Renee Zahnow. 2022. Weather and crime: A systematic review of the empirical literature. Crime Science 11 (1): 16. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-022-00179-8.

Crocitti, Stefania, and Rossella Selmini. 2017. Controlling immigrants: The latent function of Italian administrative orders. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research 23 (1): 99–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-016-9311-4.

Dorsett, Richard. 2021. A bayesian structural time series analysis of the effect of basic income on crime: Evidence from the Alaska Permanent Fund. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series A: Statistics in Society 184 (1): 179–200. https://doi.org/10.1111/rssa.12619.

Eck, John E. 2019. and Ronald V. Clarke. Situational Crime Prevention: Theory, Practice and Evidence. In Handbook on Crime and Deviance, edited by Marvin D. Krohn, Nicole Hendrix, Gina Penly Hall, and Alan J. Lizotte. Handbooks of Sociology and Social Research. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-20779-3_18

Edwards, Adam, Gordon Hughes. 2012. Public safety regimes: Negotiated orders and political analysis in criminology. Criminology & Criminal Justice 12(4):433–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895811431850

Ekman, Mats, Niklas Jakobsson. 2024. The impact of earlier pub closing hours on emergency calls to the Police during the COVID-19 pandemic in Sweden. Addiction Research & Theory 32(2):138–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/16066359.2023.2228682

Felson, Marcus, and Lawrence E. Cohen. 2017. Human Ecology and Crime: A Routine Activity Approach. In Crime Opportunity Theories, 1st ed., edited by Mangai Natarajan. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315095301-4

Gerell, Manne, Annica Allvin, Michael Frith, Torbjørn, and Skardhamar. 2022. COVID-19 Restrictions, pub Closures, and crime in Oslo, Norway. Nordic Journal of Criminology 23(2):136–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/2578983X.2022.2100966

Gianacas, Christopher, Bette Liu, and Martyn Kirk et al. 2023. Bayesian structural time series, an alternative to interrupted time series in the right circumstances. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 163(November):102–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2023.10.003

Groff, Elizabeth R.. 2014. Quantifying the exposure of street segments to drinking places nearby. Journal of Quantitative Criminology 30 (3): 527–548. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-013-9213-2.

Hood, Christopher, Helen Margetts. and Christopher Hood. 2007. The Tools of Government in the Digital Age. New ed. Public Policy and Politics. Palgrave Macmillan.

Howlett, Michael, M., and Ramesh, Anthony Perl. 2009. Studying public policy: policy cycles & policy subsystems. 3 ed. Oxford Univ. Press.

Knill, Christoph, Jale Tosun. 2012. Public policy: A new introduction. Palgrave Macmillan.

Koehler, Johann, and Friedrich Lösel. 2025. A meta-evaluative synthesis of the effects of custodial and community-based offender rehabilitation. European Journal of Criminology 22 (1): 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/14773708241256501.

Koziarski, Jacek. 2021. The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health calls for police service. Crime Science 10 (1): 22. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-021-00157-6.

Laycock, Gloria K. 2023. Routledge advances in Police practice and knowledge. In Crime, science and policing, Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003165828

Lee, YongJei, and John E.. Eck. 2019. Comparing measures of the concentration of crime at places. Crime Prevention and Community Safety 21 (4): 269–294. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41300-019-00078-2.

Linning, Shannon J., John E. Eck. 2021. Whose eyes on the street control crime? Expanding place management into neighborhoods. 1st ed. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108954143

Linning, Shannon J.., Ajima Olaghere, and John E.. Eck. 2022. Say nope to social disorganization criminology: The importance of creators in neighborhood social control. Crime Science 11 (1): 5. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40163-022-00167-y.

Maynard-Moody, Steven, Michael Musheno, and Dennis Palumbo. 1990. Street-wise social policy: Resolving the dilemma of street-level influence and successful implementation. Western Political Quarterly 43 (4): 833–848. https://doi.org/10.1177/106591299004300409.

McCannon, Bryan C., and Zachary Porreca. 2022. and Zachary Rodriguez. Three Golden Balls: Pawn Shops and Crime. SSRN Electronic Journal, ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4119571

Menchetti, Fiammetta, Fabrizio Cipollini, and Fabrizia Mealli. 2023. Combining counterfactual outcomes and ARIMA models for policy evaluation. The Econometrics Journal 26 (1): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/ectj/utac024.

Moir, Emily, Natalee Cairns, Tim Prenzler, and Susan Rayment-McHugh. 2024. A review of the impacts of business improvement districts on crime and disorder. Crime Prevention and Community Safety 26 (3): 245–265. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41300-024-00214-7.

Mourtgos, Scott M., T. Ian, and Adams, Justin Nix. 2022. Elevated Police turnover following the summer of George Floyd protests: A synthetic control study. Criminology & Public Policy 21(1):9–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12556

Nagelhout, Gera E., Karin Hummel, C. M. Moniek, Hein De De Goeij, Eileen Vries, and Kaner, Paul Lemmens. 2017. How economic recessions and unemployment affect illegal drug use: A systematic realist literature review. International Journal of Drug Policy 44(June):69–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.03.013

Nazzari, Mirko, and Moris Triventi, Marco Calaresu. 2025. Fear of crime in Context. A Cross-National longitudinal analysis of perceived unsafety in Europe, 2002–2020. Global Crime 6:1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/17440572.2025.2539853

Persak, Nina. ed. 2018. Regulation and social control of incivilities. Routledge.

Piza, Eric. 2024. CCTV Video Surveillance and Crime Control: The Current Evidence and Important Next Steps. In The Oxford Handbook of Evidence-Based Crime and Justice Policy, 1st ed., edited by Brandon C. Welsh, Steven N. Zane, and Daniel P. Mears. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197618110.001.0001

Richards, Tara N., Justin Nix, Scott M. Mourtgos, and Ian T. Adams. 2021. Comparing 911 and emergency hotline calls for domestic violence in seven cities: What happened when people started staying home due to COVID-19? Criminology & Public Policy 20(3):573–591. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12564

San Francisco Board of Supervisors. 2024. Revised Legislative Digest (Amended in Committee - July 1, 2024). Police Code - Tenderloin Retail Hours Restriction Pilot Program. https://sfgov.legistar.com/View.ashx?M=F&ID=13067126&GUID=84820AA5-FAC4-41C4-8CE7-6125E8FA31B3

Scott, Steven L., R. Hal, and Varian. 2014. Predicting the present with bayesian structural time series. International Journal of Mathematical Modelling and Numerical Optimisation 5(1/2):4. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJMMNO.2014.059942

Sierra-Arévalo, Michael, Justin Nix, and Scott M.. Mourtgos. 2023. The ‘War on Cops,’ retaliatory Violence, and the murder of George Floyd. Criminology 61 (3): 389–420. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12334.

Tebaldi, Mauro, and Marco Calaresu. 2015. Democra-city’: Bringing the city back into democratic theory for the 21st century? City Territory and Architecture 2 (1): 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40410-015-0029-2.

Tucker, Riley, T. Daniel, and O’Brien. 2024. Do commercial place managers explain crime across places? Yes and NO(PE). Journal of Quantitative Criminology 40(4):761–790. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-024-09587-2

Weisburd, David, Kevin Petersen, Cody W. Telep, and Sydney A. Fay. 2024. Can increasing preventive patrol in large geographic areas reduce crime? A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Criminology & Public Policy 23(3):721–743. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12665

Welsh, Brandon C., N. Steven, Zane, and Daniel P. Mears. 2024. Evidence-Based Crime and Justice Policy. In The Oxford Handbook of Evidence-Based Crime and Justice Policy, 1st ed., edited by Brandon C. Welsh, Steven N. Zane, and Daniel P. Mears. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780197618110.013.1

Wilcox, Pamela, Marie Skubak Tillyer. 2017. Place and neighborhood contexts. In Unraveling the Crime-Place Connection, volume 22, Routledge.

Wilcox, Pamela, and Francis T.. Cullen. 2018. Situational opportunity theories of crime. Annual Review of Criminology 1 (1): 123–148. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-criminol-032317-092421.

Wilcox, Pamela, and John E. Eck. 2011. Criminology of the unpopular: Implications for policy aimed at payday lending facilities. Criminology & Public Policy 10(2):473–482. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9133.2011.00721.x

Wilson, David B.., Charlotte Gill, Ajima Olaghere, and Dave McClure. 2016. Juvenile curfew effects on criminal behavior and victimization: A systematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews 12 (1): 1–97. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2016.3.