Introduction

The analysis of crises in professional soccer is of great importance due to their short- and long-term impacts on team performance. A crisis can be defined as a significant and often sudden disruption or downturn that threatens the stability, functioning, or success of an individual, group, organization, or system (Williams, Gruber, Sutcliffe, Shepherd, & Zhao, 2017). In professional soccer, such phases not only lead to sporting and financial losses (Druker & Daumann, 2018; Plumley, Wilson, & Shibli, 2017) but are also frequently accompanied by the dismissal of coaches (Sousa, Musa, Clemente, Sarmento, & Gouveia, 2023). These dismissals are highly visible and costly interventions: they often involve multimillion-euro severance payments, destabilize contractual and organizational planning, and may further disrupt team cohesion and performance (Lyle, 2024; Sousa et al., 2023). Beyond the financial burden, midseason changes frequently generate instability within clubs, affect long-term planning, and can even affect team performance (Sousa, Clemente, Gouveia, Field, & Sarmento, 2024a; Sousa, Sarmento, Gouveia, & Clemente, 2025). Developing systematic and objective approaches to identify crises at an early stage is therefore essential, as it may allow clubs to implement timely countermeasures and reduce reliance on reactive strategies such as managerial dismissals. This manuscript follows American English conventions; accordingly, we use the term “soccer,” which is synonymous with “football” (association football) in the European context.

The development of crises is a dynamic process often initiated by unmet expectations (Massarella, Sallu, Ensor, & Marchant, 2018). These unmet expectations can lead to psychological and emotional disturbances within a team, significantly impacting both players and management (Bar-Eli & Tenenbaum, 1989; Coutinho et al., 2017; Coutinho et al., 2018). Understanding how expectations influence the emergence of crises is essential, as it highlights the importance of recognizing early warning signs and the underlying emotional states that may contribute to a crisis. By addressing these unmet expectations and their effects, teams can implement more effective strategies to manage and mitigate the progression of a crisis (Choi, Sung, & Kim, 2010).

Theoretical perspectives, such as appraisal theories of emotion (Lazarus, 1991, pp. 89–124; Scherer, 2009) and control-process models of self-regulation (Carver & Scheier, 1990), underline that expectations function as benchmarks for evaluating performance outcomes (Berger, Fisek, Norman, & Wagner, 2018). These foundational insights explain why unmet expectations can trigger negative affective and motivational states in sport (Jekauc, Fritsch, & Latinjak, 2021). In competitive sports, high expectations—especially when unmet—have been identified as significant contributors to competition anxiety (Wiggins & Brustad, 1996), choking under pressure (Hill & Shaw, 2013), spirals of negative emotions (Jekauc et al., 2021), disruption of the psychological momentum (Taylor & Demick, 1994), and team collapse (Wergin, Mallett, Mesagno, Zimanyi, & Beckmann, 2019; Wergin, Zimanyi, Mesagno, & Beckmann, 2018). These phenomena have been shown to negatively impact performance in individual matches or tournaments. In the context of soccer, Jekauc, Vrancic, and Fritsch (2024b) demonstrated through a study involving nine professional soccer players that unmet expectations trigger complex psychological processes, leading to negative psychological states such as rumination, reduced self-confidence, increased anxiety, and overmotivation among players.

Psychological momentum is another critical factor in understanding crises in soccer, as it encapsulates the dynamic interplay between performance, perception, and motivation (Morgulev & Avugos, 2023). According to Iso-Ahola and Mobily (1980), psychological momentum is defined as an added psychological power resulting from a sequence of successes (or failures) that impacts an individual’s or team’s confidence and performance capabilities (Coulon, Barki, & Paré, 2019). In soccer, psychological momentum can manifest during the season as a team builds upon successive positive events, such as winning matches or making successful plays (Briki & Zoudji, 2019), leading to an enhanced collective belief in their ability to succeed (Jones & Harwood, 2008).

Despite these theoretical insights, research has so far lacked clear and quantifiable indicators to operationalize performance crises in football. One promising approach is to use external and objective data sources, such as betting odds or market valuations, to assess performance against expectations (Wunderlich & Memmert, 2018). Building on this idea, the present study introduces and validates three indices—Relative Position (RP), Linear Rate of Change (LRC), and Exponential Rate of Change (ERC)—which are conceptually developed in the following section. The subsequent empirical analyses apply these indices to the 2023–2024 Bundesliga season to examine their validity and practical utility in identifying and diagnosing performance crises.

Indicators of crises in soccer

Understanding and identifying crises in soccer requires a tailored approach that considers the unique psychological and scoring systems of the sport. Each sport has its own dynamics and competitive structure, which are reflected in how performances are scored and evaluated. When developing a system of crisis indicators for soccer, it is crucial to account for the specific characteristics of the sport, such as the number of tournament competitions in a season, the scoring system in each competition, and the structure of league. For the sake of clarity, we will limit ourselves in this paper to the national league in soccer, as this competition is generally the most important.

Analogous to the description of the movement of a body in physics, where position, velocity, and acceleration are central parameters (Newton, 1728), a crisis in soccer can be described by three decisive indicators: relative position in the table, linear rate of change, and exponential rate of change. All three indicators can be defined in terms of expectations of ranking and success and help to provide a comprehensive assessment of a team’s short- and long-term performance.

Relative position in the table

The relative position in the table is a primary indicator of a team’s performance within its competitive context. It is calculated based on the total points accumulated from match outcomes—three points for a win, one point for a draw, and no points for a loss. This indicator offers a straightforward view of where a team stands in relation to its competitors. However, the significance of the relative position must be considered in light of preseason expectations. A team expected to compete for the championship but finding itself mid-table or lower would be considered underperforming, whereas the same position might be satisfactory for a team expected to struggle against relegation. Therefore, the relative position must always be interpreted relative to the team’s goals and expectations. The relative position of a team in the table compared to expectations corresponds to the position of an object. This relative position is quantified by the difference between the expected table position and the actual table position, normalized by the number of teams in the league, and can be described by the following formula:

$$RP_{i,t}=\frac{E_{i,t}-A_{i,t}}{N-1}\times 100$$

(1)

where

- RPi,t:

-

is the relative position of team i on matchday t.

- Ei,t:

-

is the expected table position of team i on matchday t.

- Ai,t:

-

is the actual table position of team i on matchday t.

- N:

-

is the number of teams in the league.

- t:

-

is the matchday number.

The relative position coefficient (RPi,t) represents the difference between expected and actual position of the team i on matchday t in the table relative to the size of the league. This coefficient varies between 100, if the team with the lowest expected position in the table is at the top of the table, and −100, if the team with the highest expected position in the table is at the bottom. A coefficient of 0 indicates that the team is performing in line with its expectations. This index also considers the size of the league, meaning a deviation in table position must always be viewed relative to the league’s size. For example, a drop of three places in the table in a league with 20 teams is less significant than in a league with only 12 teams.

Due to the fact that the deviation between the expected and actual position in the table is divided by the maximum possible improvement or deterioration in the table (N − 1), this coefficient can be interpreted as the percentage deviation relative to the league size. By normalizing the difference between expected and actual positions and expressing it as a percentage, the relative position provides a clear and comparable metric for performance evaluation across different leagues.

This coefficient can be calculated for each matchday and provides a snapshot of the team’s relative position in the table. The relative position in the table, therefore, acts as a fundamental metric for assessing team performance during a season.

Linear rate of change

Similar to the velocity of an object, which indicates the rate of change of position over time, the linear rate of change describes the variation in a team’s performance over the course of a season. This rate of change can be measured by the difference between the points expected per game and the points actually achieved. A consistently negative rate of change indicates that the team is not only underperforming compared to expectations but that this trend is continuing over multiple matchdays. The linear rate of change can be calculated using the summed points difference with the following formula:

$$LRC_{it}=\sum \limits_{t=1}^{T}\left(SP_{it}-EP_{it}\right)$$

(2)

where

- LRCi,t:

-

is the linear rate of change as the summed points difference for team i on matchday t.

- SPi,t:

-

are the points actually achieved by team i on matchday t.

- EPi,t:

-

are the points expected for team i on matchday t.

- t:

-

is the matchday ranging from 1 to the current matchday T.

This equation represents the cumulative difference between actual and expected points up to the current match day and can be interpreted as the sum of the deviations between the points scored and expected points up to match day t. For example, if a team has −10 points, this means that it has scored an average of 10 points less up to matchday t than it was expected to.

The metric for expected points (EPi,t) represents the predicted number of points for team i in match t. This expectation should be based on various factors such as historical performance, opponent strength, home advantage, and is often reflected in bookmakers’ predictions. For each possible match outcome (win, draw, loss), a probability P is estimated. The sum of the probabilities for the three possible outcomes must equal 100%, thus:

$$\mathrm{P}_{win}+\mathrm{P}_{draw}+\mathrm{P}_{loss}=1$$

(3)

where

- Pwin:

-

is the probability that team i will win match t.

- Pdraw:

-

is the probability that team i will draw match t.

- Ploss:

-

is the probability that team i will lose match t.

For instance, if the estimated probabilities for a match are 60% for a win, 20% for a draw, and 20% for a loss, the expected points for the team can be calculated as follows: multiply the probability of winning (0.6) by the points awarded for a win (3), the probability of drawing (0.2) by the points awarded for a draw (1), and the probability of losing (0.2) by the points awarded for a loss (0). Adding these values together gives the expected points:

$$\begin{aligned} \mathrm{EP}_{i,t}&=3\cdot 0.6+1\cdot 0.2+0\cdot 0.2\\&=1.8+0.2=2.0 \end{aligned}$$

(4)

Thus, the expected points for the team in this match would be 2.0. EPi,t indicates how many points a team should earn on average based on the estimated probabilities for the three match outcomes. In general, the LRC index indicates the extent to which the team performs above or below expectations over the course of the season.

Exponential rate of change as psychological momentum

In sports psychology, psychological momentum refers to the perception and experience of sustained success or failure, which influences the performance and confidence of an athlete or team. A team that wins multiple games in a row can build strong positive momentum, leading to further success. Conversely, a team that repeatedly loses can experience negative momentum, resulting in further performance decline and potential crisis (Den Hartigh, Gernigon, Van Yperen, Marin, & Van Geert, 2014).

To quantitatively capture psychological momentum, the exponential rate of change (ERC) is used. This rate gives greater weight to recent games than to those played earlier in the season, thus, reflecting the current dynamics of the team. In this study, the decline in weights is modeled using the reciprocal of the golden ratio (1/φ ≈ 0.618), a mathematical constant with remarkable properties that make it particularly suitable for representing processes of decay and self-reference. The formula for the exponential rate of change is:

$$ERC_{i,t} = \sum_{t=1}^T = \varphi^{-(T-t)} \times (SP_{i,t} - EP_{i,t})$$

(5)

where

- ERCi,t:

-

is the exponential rate of change for team i on matchday t.

- SPi,t:

-

are the actual points achieved by team i on matchday t.

- EPi,t:

-

are the expected points for team i on matchday t.

- t:

-

is the matchday ranging from 1 to the current matchday T.

- φ:

-

is the golden ratio, defined as \(\frac{1+\sqrt{5}}{2}\) ≈ 1.618.

The choice of φ as a basis for the decay function is grounded in its unique mathematical characteristics. The golden ratio is defined by the self-referential equation φ = 1 + 1/φ, which means that its reciprocal is not an arbitrary number but is intrinsically linked to φ itself. This recursive property ensures that the decay process is structurally consistent and scale-invariant. Each step back in time is weighted at exactly 61.8% of the more recent one, creating a simple and elegant geometric progression that balances interpretability with precision. The half-life of this progression is approximately 1.44 matches, indicating that the influence of a given game declines by half after only one to two subsequent matchdays. Moreover, the infinite series of weights converges to φ2 ≈ 2.618, which guarantees a bounded memory span and ensures that distant matches continue to exert a diminishing but mathematically stable influence. The golden ratio also plays a central role in recursive sequences such as the Fibonacci numbers (Dunlap, 1997) and is considered the “most irrational” number, meaning that it resists approximation by rational fractions (Choi, Atena, & Tekalign, 2023; Dunlap, 1997). This property lends further stability to its use as a decay parameter because it prevents the decline pattern from collapsing into overly simple or oscillatory forms.

By adopting 1/φ as the decay factor, the ERC captures the recency of performance in a way that is mathematically elegant, psychologically plausible, and dynamically stable. The most recent results dominate the momentum index, but earlier performances continue to exert some influence, fading in a self-similar and structurally consistent manner. Consequently, ERC is highly sensitive to current performance trends and provides an incisive measure of psychological momentum. A high positive ERC value indicates that the team has positive momentum, suggesting a sequence of performances that exceed expectations. Conversely, a high negative ERC value indicates that the team has negative momentum and may be on the path to a crisis or already in one. An ERC value near zero means that the team has been performing in line with expectations in recent games and exhibits neither positive nor negative momentum.

Integration of the indicators

The three proposed indicators—RP, LRC, and ERC—form a cohesive framework for analyzing team performance in professional soccer. These metrics offer distinct but complementary insights, enabling a nuanced understanding of both the gradual and acute dynamics of performance crises. The RP index serves as a macroscopic measure of performance by quantifying the deviation of a team’s actual league standing from preseason expectations. The LRC focuses on cumulative performance trends by comparing actual points accrued to expected points over successive matchdays. This metric is particularly useful for detecting subtle, incremental shifts in performance. The ERC emphasizes recent performance by assigning greater weight to outcomes in the most recent matches. By capturing abrupt changes in momentum, ERC provides an early warning for potential tipping points. When integrated, these indicators create a multidimensional assessment framework that captures both the cumulative and immediate aspects of performance dynamics.

Methods

Study design and context

This study examined all mid-season coach dismissals in the 2023–2024 Bundesliga as markers of performance crises. The Bundesliga, as one of the top-tier soccer leagues globally, operates in a highly competitive environment with immense expectations on teams (Pieper, Nüesch, & Franck, 2012). Given the significant financial investments and high stakes involved, the performance of a team is under constant scrutiny from management, fans, and the media (Sousa et al., 2023). Coach suspensions or dismissals are frequent responses to prolonged underperformance, often following deviations from expected league position, accumulated points, and recent match outcomes (Allen & Chadwick, 2012; Lago-Peñas, 2011; Sousa et al., 2024a; Sousa, Sarmento, Gouveia, & Clemente, 2024b). For our purposes, mid-season coach dismissals were used as observable crisis markers, allowing validation of the proposed indices in a highly competitive setting.

Data collection

To validate the three crisis indices—RP, LRC, and ERC—we analyzed all instances of coach suspensions in the 1. Bundesliga during the 2023–2024 season. Only cases where a coach was suspended during the current season (matchdays 1 to 34) were included, focusing on mid-season changes indicative of performance crises.

Expected table position

The Expected Table Position was determined by combining squad market valuation and final league standings from the 2022–2023 season. Market values as of 15 August 2023, the last day of the first transfer period, were obtained from Transfermarkt (transfermarkt.de) and reflect the team’s economic potential. Concurrently, final league standings from the 2022–2023 season were sourced from official records such as Kicker (www.kicker.de). The expected position was calculated as the average of the market value rank and the previous season’s league rank, providing a balanced performance expectation based on economic and historical indicators.

Expected points

The EP for each match were derived from prematch betting odds obtained from Oddsportal (www.oddsportal.com). First, betting odds for win, draw, and loss outcomes were converted into implied probabilities using the formula 1/odds. Since bookmakers include a margin, probabilities initially summed to more than 100%. To correct this, probabilities were normalized by dividing each by their total sum. Finally, EP was calculated by multiplying the adjusted probabilities with their corresponding points (win = 3, draw = 1, loss = 0) and summing the results. This approach provided a statistically robust estimate of a team’s expected points per match.

Data analysis

The analysis evaluated how the crisis indices captured team performance dynamics during the 2023–2024 Bundesliga season and aligned with observable crisis events, such as coaching dismissals. RP, LRC, and ERC values were calculated for all 18 Bundesliga teams on a per-matchday basis using the formulas outlined in the section “Indicators of crisis in soccer”. These calculations, performed in Microsoft Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA, USA), ensured consistency in processing match outcomes and preseason expectations.

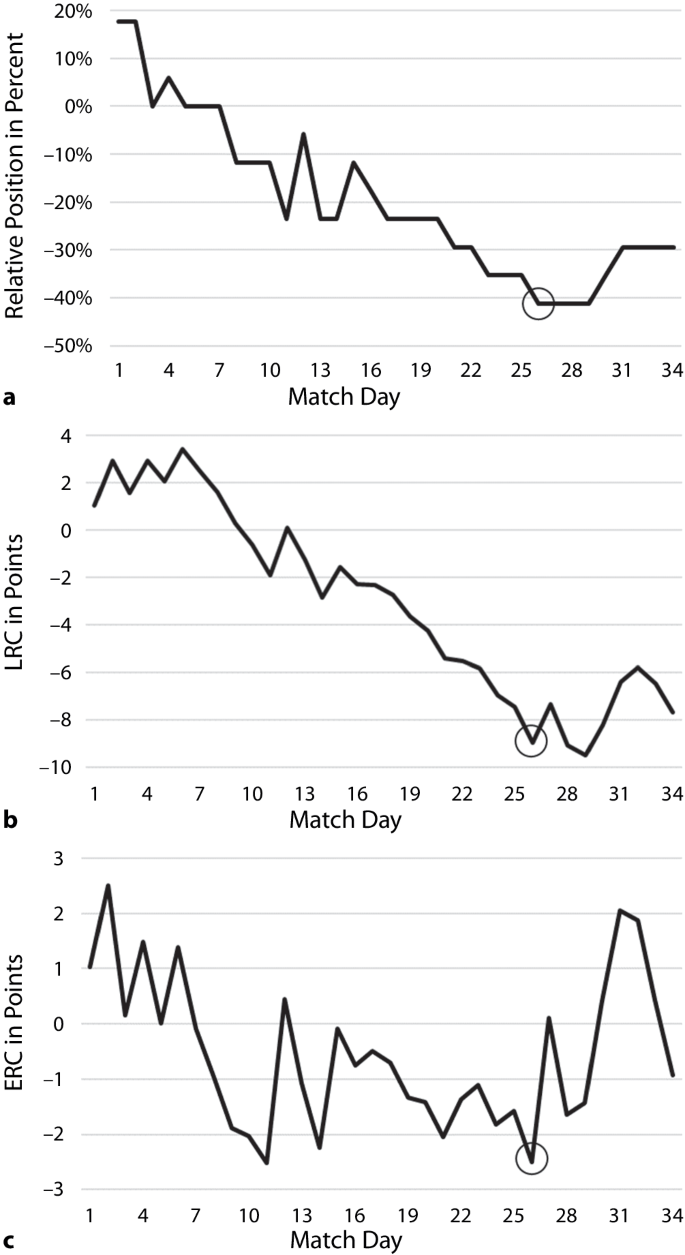

The computed indices were summarized with descriptive statistics, including mean, standard deviation, and range, for each team across the season (Table 1). To explore the relationship between index patterns and managerial decisions, we analyzed the eight documented coach dismissals, focusing on RP, LRC, and ERC values immediately preceding these events (Table 2). To provide detailed insights, time-series visualizations were created for two selected case studies: FC Augsburg and VfL Wolfsburg. These teams demonstrated contrasting crisis trajectories, with FC Augsburg encountering early-season challenges and VfL Wolfsburg facing a late-season downturn. The visualizations traced the evolution of RP, LRC, and ERC over the season (Figs. 1 and 2).

Development of the crisis indices for FC Augsburg with the time point of the coach’s dismissal: a relative position, b linear rate of change (LRC), c exponential rate of change (ERC)

Development of the crisis indices for Vfl Wolfsburg with the time point of the coach’s dismissal: a relative position, b linear rate of change (LRC), c exponential rate of change (ERC)

Results

Descriptive overview of all indices

The analysis of the crisis indices—RP, LRC, and ERC—for the Bundesliga 2023–2024 season, as presented in Table 1, highlights substantial heterogeneity in team performance, emphasizing variations in both relative standings and performance trajectories. The RP metric yielded an overall mean of 0.36 with a standard deviation (SD) of 25.90, suggesting that while teams generally aligned with their expected standings, there was notable dispersion. Teams such as VfB Stuttgart (mean RP = 58.48) and 1. FC Heidenheim 1846 (mean RP = 34.43) markedly outperformed their projected positions, whereas 1. FC Union Berlin (−36.68) and 1. FSV Mainz 05 (−31.83) exhibited pronounced underperformance, underscoring significant deviations from expectations.

The LRC, which encapsulates cumulative performance trends over the season, recorded an aggregate mean of −0.07 (SD = 5.88). This mean implies a general equilibrium in over- and underperformance across the league. Nonetheless, teams like Bayer 04 Leverkusen demonstrated exceptional positive LRC values (mean = 11.37), indicating sustained periods of overachievement. In contrast, 1. FSV Mainz 05 (−9.48) and 1. FC Köln (−7.59) experienced considerable negative LRC values, reflecting persistent and pronounced declines in performance.

The ERC, designed to capture recent performance dynamics and psychological momentum, presented an overall mean of −0.05 (SD = 1.29), indicative of a mean zero momentum across the league and all matchdays. Teams such as Bayer 04 Leverkusen (1.48) and VfB Stuttgart (1.06) displayed significantly positive ERC values, denoting robust recent performance. Conversely, 1. FC Köln (−0.76) and 1. FSV Mainz 05 (−0.79) were characterized by marked negative ERC values, signaling acute performance deterioration.

Coach suspension events as markers of crisis

The data presented in Table 2 highlight key patterns associated with the eight documented coach dismissals. First, the RP values were uniformly negative or zero, underscoring that teams consistently underperformed relative to preseason expectations or, in cases such as VfL Bochum, performed precisely at the expected threshold. VfL Bochum’s expected 15th-place position offered minimal leeway for underperformance in the rankings, further contextualizing their outcome. This consistent deviation from expected rankings signifies systemic underachievement.

Second, the LRC metrics were universally negative, reflecting an accumulation of points below expected performance levels leading up to the dismissals. This trend emphasizes the prolonged nature of the underperformance, spanning multiple matchdays, as opposed to transient or isolated downturns.

Most critically, the ERC, which captures recent performance momentum, revealed pronounced declines. In six of the eight cases (FC Augsburg, VfL Bochum, 1. FSV Mainz 05 on matchday 21, 1. FC Union Berlin on matchdays 11 and 32, and VfL Wolfsburg), ERC values dropped below −2.0 at or immediately preceding the dismissal, signifying sharp negative momentum. Even in the two exceptions where ERC did not breach the −2.0 threshold (1. FC Köln at −1.53 and 1. FSV Mainz 05 at −1.32 on matchday 9), the values remained firmly within a negative trajectory and subsequently fell below the −2.0 mark a few matchdays prior to the dismissal. This timing underscores the role of acute performance deterioration in decision-making, as it indicates a critical threshold that likely influenced the dismissals. These results suggest that while persistently negative LRC values and subpar RP scores may signal broader underperformance, it is the acute downturn in ERC, reflecting recent momentum loss, that often aligns most closely with the timing of a coach’s dismissal.

Illustrative case examples: Augsburg and Wolfsburg

To demonstrate the practical utility of the proposed indices, we examine two cases from the 2023–2024 Bundesliga season: FC Augsburg and VfL Wolfsburg. These clubs exemplify contrasting crisis trajectories, with Augsburg experiencing an early-season downturn and VfL Wolfsburg facing a later collapse (Figs. 1 and 2).

FC Augsburg entered the season with moderate expectations, based on a 15th-place finish in the previous year and a squad market value ranking 12th in the league (≈ 13.5 expected table position). After seven matchdays, however, the team had collected only five points and suffered a critical home defeat to SV Darmstadt 98, leading to the dismissal of head coach Enrico Maaßen. At this point, the indices signaled a clear crisis: RP = −8.8% indicated underperformance relative to expectations, LRC = −2.57 reflected a cumulative deficit in achieved versus expected points, and ERC = −2.00 captured an acute downturn in recent matches. The simultaneous drop across all indices, particularly the sharp ERC decline close to −2.0, marked a tipping point for managerial intervention.

VfL Wolfsburg, by contrast, started the season strongly. With a market value ranking 6th and an expected table position of 7th, the team earned 12 points in the first six matches (LRC = +3.43), performing above expectations. Yet after Matchday 6, all indices began to decline. Between Matchdays 10 and 14, the ERC fell below −2.0 three times, indicating repeated lapses in short-term momentum. By Matchday 26, following a home defeat to FC Augsburg, the team had slipped to 14th place in the standings. The indices at that point painted a severe picture: RP = −41.2%, LRC = −8.98, and ERC = −2.64, highlighting both chronic underperformance and acute negative momentum. This situation culminated in the dismissal of head coach Nico Kovač.

Taken together, the FC Augsburg and VfL Wolfsburg cases demonstrate how the indices capture different crisis dynamics. FC Augsburg’s early-season downturn reflected a rapid deterioration that quickly crossed critical thresholds, while Wolfsburg’s decline was more gradual yet equally severe by the time of intervention. In both cases, pronounced ERC drops aligned closely with managerial changes, underscoring the diagnostic value of combining RP, LRC, and ERC in identifying performance crises.

Discussion

This study introduced and initially validated three crisis indices to quantify and analyze performance crises in professional soccer. Inspired by concepts in physics, where position, velocity, and acceleration describe the movement of a body, these indices capture distinct facets of team performance, collectively providing a comprehensive framework for assessing and diagnosing crises during a season.

The practical application of these indices was demonstrated through case studies of FC Augsburg and VfL Wolfsburg. Augsburg dismissed its head coach early in the season (Matchday 7) following consistent underperformance across all three indices, including an acute ERC decline to −2.0, which likely served as the critical tipping point. In contrast, Wolfsburg delayed managerial intervention until Matchday 26, despite gradual deterioration in RP and LRC and intermittent ERC declines below −2.0. By the time of the coach’s dismissal, Wolfsburg’s indices indicated a severe crisis, with RP at −41.18%, LRC at −8.98, and ERC at −2.49, highlighting sustained and acute underperformance. Across the league, teams experiencing coaching changes exhibited a consistent pattern of negative RP values, significant LRC deficits, and sharp ERC declines prior to dismissals.

Theoretical implications

This study enhances the theoretical understanding of performance crises in professional soccer by integrating psychological, motivational, and performance-based frameworks. The proposed indices bridge theoretical constructs with measurable phenomena, providing a structured approach to understanding crises. The RP index, quantifying deviations from expected performance, aligns with theories of unmet expectations, such as the self-fulfilling prophecy (Rosenthal & Jacobson, 1968), appraisal theories of emotion (Lazarus, 1991), and self-regulation theories (Carver & Scheier, 1990). By operationalizing abstract concepts into quantifiable deviations, the RP metric links theoretical expectations with actual performance.

The LRC and ERC indices further capture crisis dynamics. The LRC aligns with Hardy’s (1996) catastrophe model and Buenemann, Raue-Behlau, Tamminen, Tietjens, and Strauss (2023) model for performance crises, as it reflects cumulative performance trends and the accumulation of setbacks. The ERC, emphasizing recent performance and psychological momentum, incorporates insights from motivation theories, such as Iso-Ahola and Mobily’s (1980) conceptualization of psychological momentum. By weighting recent results more heavily, the ERC measures how short-term successes or failures shape a team’s trajectory and decisions. This study highlights that acute ERC declines—often below −2.0—serve as critical tipping points for managerial decisions, such as coach dismissals. This aligns with catastrophe theories in sports psychology (Hardy, 1996), which suggest small changes can lead to dramatic outcomes. Additionally, the findings support the downward spiral model (Jekauc et al., 2024b), where crises are perpetuated by negative momentum at individual and team levels.

A complementary body of evidence indicates that executive functions and perceptual–cognitive skills (e.g., visual search efficiency, inhibition, cognitive flexibility) are associated with faster decisions, greater game intelligence, and more game time in elite soccer (Ali, 2011; Sakamoto, Takeuchi, Ihara, Ligao, & Suzukawa, 2018; Verburgh, Scherder, van Lange, & Oosterlaan, 2014; Vestberg, Reinebo, Maurex, Ingvar, & Petrovic, 2017). These mechanisms offer a micro-level account for macro-level patterns captured by our indices: erosion in decision efficiency or cognitive control could depress short-horizon outcomes (ERC) and, if persistent, accumulate into negative trends (LRC) and rank shortfalls (RP). Empirically, elite/subelite contrasts and talent-pathway studies repeatedly show advantages in these functions among stronger performers, consistent with resilience against pressure-induced performance dips (Huijgen et al., 2015). Recent work also profiles psychological characteristics of elite players, reinforcing that cognitive control and related traits contribute to performance stability (Bonetti et al., 2025). Integrating such player-level measures with team-level indices could clarify why some squads weather adverse sequences without tipping into crisis while others do not.

Practical implications

The findings of this study offer substantial practical value for stakeholders in professional soccer, including team managers, coaches, analysts, and sports psychologists. The proposed crisis indices provide a data-driven framework for identifying, monitoring, and addressing performance crises, enabling timely and effective interventions. For team management and coaching staff, the indices can serve as diagnostic tools to assess team performance against preseason expectations and detect early warning signs of crises (Bodik, Goldszmidt, Fox, Woodard, & Andersen, 2010). For sports psychologists, the indices provide an empirical foundation to understand and address the psychological aspects of team performance.

Beyond signaling the presence of crises, the indices can also guide the selection and timing of interventions. Declines in RP, LRC, or ERC may point to different intervention needs: tactical adjustments (e.g., reforming training loads or game concepts), methodological innovations (e.g., adapting match preparation routines), or psychological strategies (e.g., fostering motivation and confidence) (Brown-Devlin, 2018; Memmert, 2015; Memmert & Furley, 2007). However, across these domains, the central factor for recovery is resilience—at the level of individual players (Sarkar & Fletcher, 2014), the team as a collective (Morgan, Fletcher, & Sarkar, 2017), and the club as an organization (Bradley & Alamo-Pastrana, 2022; Fasey, Sarkar, Wagstaff, & Johnston, 2021). Resilience determines whether setbacks trigger further deterioration or are absorbed and transformed into opportunities for adaptation and growth (Bryan, O’Shea, & MacIntyre, 2019). Strengthening resilience, for example, through psychological skills training (Precious & Lindsay, 2019), mindfulness training (Jekauc, Mülberger, & Weyland, 2024a), leadership development (Redmond, 2013), or cohesive team cultures (López-Gajardo, García-Calvo, González-Ponce, Díaz-García, & Leo, 2022), may therefore be the most effective way to mitigate crises once early warning signals are detected. The indices presented here can contribute by providing timely feedback on whether such resilience-building measures are translating into measurable improvements in performance dynamics.

In practice, the indices can be paired with simple perceptual–cognitive monitoring to anticipate inflection points. For example, periodic assessments of decision-making response time and visual search behavior in representative tasks, alongside tracking of cognitive effort, can flag impending short-term dips even before ERC falls sharply (Cardoso, Afonso, Roca, & Teoldo, 2021). When ERC begins to deteriorate, staff may prioritize interventions that target decision efficiency (representative, time/space-constrained drills), cognitive control (inhibition/flexibility tasks), and load management of cognitive effort during congested periods (Cardoso et al., 2021). This aligns with evidence that executive functions and game intelligence relate to playing time and availability, and suggests a player-level lever to stabilize team-level momentum (Scharfen & Memmert, 2021).

Reflection on managerial decisions in practice

The present findings also invite reflection on the broader realities of managerial decisions in high-performance football. For instance, VfL Wolfsburg did not dismiss their coach immediately despite declining indices (Sousa et al., 2024a), illustrating that clubs sometimes tolerate prolonged underperformance before acting (Lyle, 2024). Prior research suggests that retaining a coach can, in some cases, be more beneficial than dismissal, as continuity may prevent additional financial costs, organizational disruptions, and performance instability (e.g., Heuer, Müller, Rubner, Hagemann, & Strauss, 2011; Rausch et al., 2025; Sousa et al., 2024a; Stachnik & Wolak, 2025). Moreover, the outcomes of dismissals are not determined by the timing alone but also by the profile and leadership qualities of the successor (Karayel, Adilogullari, & Senel, 2024; Kattuman, Loch, & Kurchian, 2019). Studies indicate that players may respond more positively to coaches with specific leadership qualities or communication styles, which can influence whether a crisis is successfully resolved (e.g., Sousa et al., 2025). Thus, while the indices introduced here can signal crises with precision, their practical effectiveness ultimately depends on how clubs interpret these signals and align them with broader strategic and managerial considerations.

Limitations and future directions

While this study provides a robust framework for quantifying and analyzing performance crises in professional soccer, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the analysis is confined to a single season (2023–2024) within one national league (the Bundesliga). While this provides a focused snapshot of performance crises in a highly competitive context, the findings cannot be assumed to generalize across seasons or leagues. Broader validation over multiple years and in other major leagues (e.g., Premier League, La Liga, Serie A) is needed to establish the robustness and universality of the RP, LRC, and ERC indices. Expanding to diverse contexts would also allow exploration of structural factors (e.g., league format, relegation pressure, cultural differences in managerial stability) that may shape crisis dynamics.

Second, the study relies exclusively on league performance data, which limits the scope of the analysis. Other competitions, such as the DFB Cup and international tournaments like the Champions League, Europa League, and Conference League, play a critical role in shaping stakeholder expectations and influencing team dynamics. Future studies should incorporate data from these competitions to provide a more holistic assessment of team performance and the fulfillment of expectations.

Third, the analyses presented here are retrospective in nature. While the indices successfully captured patterns preceding actual dismissals, no prospective validation was attempted to test whether these indices can predict crises in real time before managerial decisions occur. Future studies should examine predictive validity, for example, by applying the indices to ongoing seasons or unseen data, to determine whether crisis thresholds (e.g., ERC falling below −2.0) reliably forecast forthcoming dismissals or downturns. Such predictive testing would considerably enhance the practical utility of the indices for clubs and analysts.

Fourth, a further limitation concerns the lack of consideration of the coaches’ backgrounds and profiles in the present analysis. Factors such as career stage, tenure at the club, and prior experience in managing crises can strongly influence both the likelihood of dismissal and the effectiveness of subsequent recovery efforts. For example, a coach early in their career or with limited time at a club may have less organizational capital or authority, making them more vulnerable to dismissal during downturns. Conversely, experienced coaches with established reputations may receive greater tolerance from management despite negative indices. Future research should therefore integrate information on coach profiles to better understand how individual characteristics interact with quantitative performance indicators in shaping crisis trajectories and managerial decisions.

Lastly, this study emphasizes the importance of quantitative analysis but does not integrate qualitative aspects of crisis development, such as psychological insights from team members or organizational dynamics within clubs. Previous qualitative work with professional players and coaches has already shown that unmet expectations play a central role in triggering crises (Jekauc et al., 2024b). Building on this foundation, future studies could explicitly connect expectations concerning table position and match outcomes to the trajectories of RP, LRC, and ERC. For instance, combining player and coach interviews with the monitoring of crisis indices could reveal how subjective perceptions of underperformance align with or diverge from quantitative signals. Such mixed-methods approaches would provide valuable explanatory depth and complement the diagnostic power of the indices.

Conclusion

This study introduced and validated three crisis indices to provide a quantitative framework for diagnosing performance crises in professional soccer. Inspired by physical principles describing motion, these indices offer a systematic way to evaluate team performance based on preseason expectations, cumulative trends, and short-term momentum shifts. Applied to the 2023–2024 Bundesliga season, the indices identified both gradual declines and sudden downturns in performance. The practical utility of the indices was demonstrated through illustrative case studies of FC Augsburg and VfL Wolfsburg, which highlighted the contrasting dynamics of early versus late managerial interventions.

References

Ali, A. (2011). Measuring soccer skill performance: a review. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 21(2), 170–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0838.2010.01256.x.

Allen, W. D., & Chadwick, C. (2012). Performance, expectations, and managerial dismissal:evidence from the national football league. Journal of Sports Economics, 13(4), 337–363. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527002512450257.

Bar-Eli, M., & Tenenbaum, G. (1989). A theory of individual psychological crisis in competitive sport. Applied Psychology, 38(2), 107–120.

Berger, J., Fisek, M. H., Norman, R. Z., & Wagner, D. G. (2018). Formation of reward expectations in status situations. In J. Berger & M. Zeldrich (Eds.), Status, power, and legitimacy (pp. 121–154). Routledge.

Bodik, P., Goldszmidt, M., Fox, A., Woodard, D. B., & Andersen, H. (2010). Fingerprinting the datacenter: automated classification of performance crises. Proceedings of the 5th European conference on Computer systems.

Bonetti, L., Vestberg, T., Jafari, R., Seghezzi, D., Ingvar, M., Kringelbach, M. L., Filgueiras, A., & Petrovic, P. (2025). Decoding the elite soccer player’s psychological profile. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(3), e2415126122. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2415126122.

Bradley, E. H., & Alamo-Pastrana, C. (2022). Dealing with unexpected crises: organizational resilience and its discontents. In S. Shortell, L. Burns & J. Hefner (Eds.), Responding to the grand challenges in health care via organizational innovation: needed advances in management research (pp. 1–21). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Briki, W., & Zoudji, B. (2019). Gaining or losing team ball possession: the dynamics of momentum perception and strategic choice in football coaches [original research]. Frontiers in Psychology, 10,1019. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01019.

Brown-Devlin, N. (2018). Experimentally examining crisis management in sporting organizations. In A. Billings & W. B. K. A. Coombs (Eds.), Reputational challenges in sport (pp. 41–55). Routledge.

Bryan, C., O’Shea, D., & MacIntyre, T. (2019). Stressing the relevance of resilience: a systematic review of resilience across the domains of sport and work. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 12(1), 70–111. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2017.1381140.

Buenemann, S., Raue-Behlau, C., Tamminen, K. A., Tietjens, M., & Strauss, B. (2023). A conceptual model for performance crises in team sport: a narrative review. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 18(2), 823-848. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2023.2291799.

Cardoso, F. S. L., Afonso, J., Roca, A., & Teoldo, I. (2021). The association between perceptual-cognitive processes and response time in decision making in young soccer players. Journal of Sports Sciences, 39(8), 926–935. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2020.1851901.

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (1990). Origins and functions of positive and negative affect: a control-process view. Psychological Review, 97(1), 19–35.

Choi, J., Atena, A., & Tekalign, W. (2023). The most irrational number that shows up everywhere: the golden ratio. Journal of Applied Mathematics and Physics, 11(4), 1185–1193.

Choi, J. N., Sung, S. Y., & Kim, M. U. (2010). How do groups react to unexpected threats? Crisis management in organizational teams. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 38(6), 805–828.

Coulon, T., Barki, H., & Paré, G. (2019). Conceptualizing project team momentum: a review of the sports literature. International Journal of Managing Projects in Business, 14(2), 270–299. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMPB-11-2018-0263.

Coutinho, D., Gonçalves, B., Travassos, B., Wong, D. P., Coutts, A. J., & Sampaio, J. E. (2017). Mental fatigue and spatial references impair soccer players’ physical and tactical performances [original research]. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1645. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01645.

Coutinho, D., Gonçalves, B., Wong, D. P., Travassos, B., Coutts, A. J., & Sampaio, J. (2018). Exploring the effects of mental and muscular fatigue in soccer players’ performance. Human Movement Science, 58, 287–296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.humov.2018.03.004.

Den Hartigh, R. J. R., Gernigon, C., Van Yperen, N. W., Marin, L., & Van Geert, P. L. C. (2014). How psychological and behavioral team states change during positive and negative momentum. PLoS ONE, 9(5), e97887. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0097887.

Druker, K., & Daumann, F. (2018). Wirtschaftliche Krisen im Profifußball: Eine systematische Literaturübersicht. In J. Königstorfer (Ed.), Innovationsökonomie und -management im Sport (pp. 65–85). Hofmann.

Dunlap, R. A. (1997). The golden ratio and Fibonacci numbers. World Scientific.

Fasey, K. J., Sarkar, M., Wagstaff, C. R. D., & Johnston, J. (2021). Defining and characterizing organizational resilience in elite sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 52, 101834. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101834.

Hardy, L. (1996). Testing the predictions of the cusp catastrophe model of anxiety and performance. The sport psychologist, 10(2), 140–156.

Heuer, A., Müller, C., Rubner, O., Hagemann, N., & Strauss, B. (2011). Usefulness of dismissing and changing the coach in professional soccer. PLoS ONE, 6(3), e17664. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0017664.

Hill, D. M., & Shaw, G. (2013). A qualitative examination of choking under pressure in team sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14(1), 103–110.

Huijgen, B. C., Leemhuis, S., Kok, N. M., Verburgh, L., Oosterlaan, J., Elferink-Gemser, M. T., & Visscher, C. (2015). Cognitive functions in elite and sub-elite youth soccer players aged 13 to 17 years. PLoS ONE, 10(12), e144580.

Iso-Ahola, S. E., & Mobily, K. (1980). “Psychological momentum”: a phenomenon and an empirical (unobtrusive) validation of its influence in a competitive sport tournament. Psychological Reports, 46(2), 391–401. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1980.46.2.391.

Jekauc, D., Fritsch, J., & Latinjak, A. T. (2021). Toward a theory of emotions in competitive sports. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 790423. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.790423.

Jekauc, D., Mülberger, L., & Weyland, S. (2024a). Mindfulness training in sports: the exercise program for enhancing athletic performance. Springer.

Jekauc, D., Vrancic, D., & Fritsch, J. (2024b). Insights from elite soccer players: understanding the downward spiral and the complex dynamics of crises. German Journal of Exercise and Sport Research, 54, 429-441. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12662-024-00968-0.

Jones, M. I., & Harwood, C. (2008). Psychological momentum within competitive soccer: Players’ perspectives. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 20(1), 57–72.

Karayel, E., Adilogullari, I., & Senel, E. (2024). The role of transformational leadership in the associations between coach-athlete relationship and team resilience: a study on elite football players. BMC Psychology, 12(1), 514. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-02043-7.

Kattuman, P., Loch, C., & Kurchian, C. (2019). Management succession and success in a professional soccer team. PLoS ONE, 14(3), e212634.

Lago-Peñas, C. (2011). Coach mid-season replacement and team performance in professional soccer. Journal of Human Kinetics, 28(2011), 115–122.

Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Emotion and adaptation. Oxford University Press.

López-Gajardo, M. A., García-Calvo, T., González-Ponce, I., Díaz-García, J., & Leo, F. M. (2022). Cohesion and collective efficacy as antecedents and team performance as an outcome of team resilience in team sports. International Journal of Sports Science & Coaching, 18(6), 2239–2250. https://doi.org/10.1177/17479541221129198.

Lyle, J. (2024). Appointed on responsibility, sacked on accountability: understanding involuntary termination in football management. What can we learn from coaching studies. International Journal of Management and Decision Making, 23(2), 210–227. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijmdm.2024.137014.

Massarella, K., Sallu, S. M., Ensor, J. E., & Marchant, R. (2018). REDD+, hype, hope and disappointment: the dynamics of expectations in conservation and development pilot projects. World Development, 109, 375–385. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2018.05.006.

Memmert, D. (2015). Teaching tactical creativity in sport: research and practice. Routledge.

Memmert, D., & Furley, P. (2007). “I spy with my little eye!”: breadth of attention, inattentional blindness, and tactical decision making in team sports. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 29(3), 365–381. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.29.3.365.

Morgan, P. B. C., Fletcher, D., & Sarkar, M. (2017). Recent developments in team resilience research in elite sport. Current Opinion in Psychology, 16, 159–164. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.05.013.

Morgulev, E., & Avugos, S. (2023). Beyond heuristics, biases and misperceptions: the biological foundations of momentum (hot hand). International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 16(1), 155–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2020.1830426.

Newton, I. (1728). The mathematical principles of natural philosophy. B. Motte.

Pieper, J., Nüesch, S., & Franck, E. (2012). How expectations affect managerial change

Plumley, D. J., Wilson, R., & Shibli, S. (2017). A holistic performance assessment of English Premier League football clubs 1992–2013. Journal of Applied Sport Management, 9(1).

Precious, D., & Lindsay, A. (2019). Mental resilience training. Journal of the Royal Army Medical Corps, 165(2), 106–108. https://doi.org/10.1136/jramc-2018-001047.

Rausch, C., Fritsch, J., Altmann, S., Steindorf, L., Spielmann, J., & Jekauc, D. (2025). Leading through performance crises: soccer coaches’ insights on their strategies—a qualitative study. Frontiers in Psychology, 16, 1576717. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2025.1576717.

Redmond, S. (2013). An explorative study on the connection between leadership skills, resilience and social support among youth. Galway: National University of Ireland.

Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom. The Urban Review, 3(1), 16–20.

Sakamoto, S., Takeuchi, H., Ihara, N., Ligao, B., & Suzukawa, K. (2018). Possible requirement of executive functions for high performance in soccer. PLoS ONE, 13(8), e201871.

Sarkar, M., & Fletcher, D. (2014). Psychological resilience in sport performers: a review of stressors and protective factors. Journal of Sports Sciences, 32(15), 1419–1434. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2014.901551.

Scharfen, H.-E., & Memmert, D. (2021). Fundamental relationships of executive functions and physiological abilities with game intelligence, game time and injuries in elite soccer players. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 35(6), 1535–1546. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3886.

Scherer, K. R. (2009). The dynamic architecture of emotion: evidence for the component process model. Cognition and emotion, 23(7), 1307–1351.

Sousa, H., Musa, R. M., Clemente, F. M., Sarmento, H., & Gouveia, É. R. (2023). Physical predictors for retention and dismissal of professional soccer head coaches: an analysis of locomotor variables using logistic regression pipeline. Frontiers in Sports and Active Living, 5, 1301845. https://doi.org/10.3389/fspor.2023.1301845.

Sousa, H., Clemente, F., Gouveia, É., Field, A., & Sarmento, H. B. (2024a). Effects of changing the head coach on soccer team’s performance: a systematic review. Biology of Sport, 41(2), 83–94. https://doi.org/10.5114/biolsport.2024.131816.

Sousa, H., Sarmento, H., Gouveia, E., & Clemente, F. M. (2024b). Perception of professional Portuguese soccer players about the replacement of leadership with the season underway—a qualitative study. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 25(4), 653-674. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2024.2436802.

Sousa, H., Sarmento, H., Gouveia, É. R., & Clemente, F. M. (2025). Perception of professional Portuguese soccer players about the replacement of leadership with the season underway—a qualitative study. International Journal of Performance Analysis in Sport, 25(4), 653–674. https://doi.org/10.1080/24748668.2024.2436802.

Stachnik, B., & Wolak, J. (2025). Managerial Turnover and Performance: Lessons from the Polish Extraklasa. Scientific Papers of Silesian University of Technology. Organization. Management. https://doi.org/10.29119/1641-3466.2025.218.33.

Taylor, J., & Demick, A. (1994). A multidimensional model of momentum in sports. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 6(1), 51–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/10413209408406465.

Verburgh, L., Scherder, E. J., van Lange, P. A., & Oosterlaan, J. (2014). Executive functioning in highly talented soccer players. PLoS ONE, 9(3), e91254.

Vestberg, T., Reinebo, G., Maurex, L., Ingvar, M., & Petrovic, P. (2017). Core executive functions are associated with success in young elite soccer players. PLoS ONE, 12(2), e170845.

Wergin, V. V., Zimanyi, Z., Mesagno, C., & Beckmann, J. (2018). When suddenly nothing works anymore within a team–Causes of collective sport team collapse. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2115.

Wergin, V. V., Mallett, C. J., Mesagno, C., Zimanyi, Z., & Beckmann, J. (2019). When you watch your team fall apart–coaches’ and sport psychologists’ perceptions on causes of collective sport team collapse. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1331.

Wiggins, M. S., & Brustad, R. J. (1996). Perception of Anxiety and Expectations of Performance. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 83(3), 1071–1074. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1996.83.3.1071.

Williams, T. A., Gruber, D. A., Sutcliffe, K. M., Shepherd, D. A., & Zhao, E. Y. (2017). Organizational Response to Adversity: Fusing Crisis Management and Resilience Research Streams. Academy of Management Annals, 11(2), 733–769. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2015.0134.

Wunderlich, F., & Memmert, D. (2018). The betting odds rating system: Using soccer forecasts to forecast soccer. PLoS ONE, 13(6), e198668. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0198668.