Abstract

Studies exploring the effects of music on cognitive processes in humans, particularly classical music compositions such as Mozart’s Sonatas, have emphasized its positive effects of music listening on mood and different cognitive functions. The current investigation intended to evaluate the impact of passively listening to Mozart’s Sonata K448 on emotional, cognitive, and brain activity parameters in adult healthy participants. Following the music-listening period (9:26 min) employed in the experimental versus a control group without musical stimulation, participants immediately completed a mood questionnaire followed by a working memory (WM) task with online event-related EEG acquisition. The experimental group demonstrated higher WM performance scores versus the control group. Quantitative EEG (qEEG) analysis under frontoparietal electrodes indicated significantly lower mean beta power during rest, encoding, and retention time-windows under the left prefrontal F7 electrode in the experimental group versus controls. In addition, music-listening resulted in higher frontal alpha power in the experimental group compared to the control group during WM-encoding intervals. These findings may have valuable applications in the clinical settings, supporting the integration of musical interventions in the treatment of various neurodevelopmental populations to enhance working memory functioning, stabilize mood, and to optimize verbal WM functioning.

Introduction

Throughout history, humans have consistently desired to develop musical instruments and produce melodies that “please the soul” generating pleasure-related sensations and changes in emotional states. Music has a significant functional role in our daily routines and can affect the emotional (Dingle et al., 2021; Groarke et al., 2020), mental (Dingle et al., 2021; Gustavson et al., 2021), and cognitive (Kasuya-Ueba et al., 2020; Kang, 2023; Reybrouck et al., 2021; Weinberger, 2004) state of the listener.

Researchers have studied the effects of music on mental processes (Kang, 2023), physiological responses (Delleli et al., 2023), and cognitive functioning (Giannouli et al., 2024) in passive listeners. For example, recreational music-listening is significantly associated with decreased heart rate, lower blood pressure, and slower respiratory rate in individuals of age 60 years or older. Other studies have examined the effect of listening to music in people diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD) indicating a reduction in MDD symptom severity following musical stimulation periods (Castillo-Pérez et al., 2010; Leubner & Hinterberger, 2017). The musical exposure also evoked positive emotions in individuals with MDD who listened to music compared to those who did not (Castillo-Pérez et al., 2010; Leubner & Hinterberger, 2017). Previous studies have also demonstrated a significant relationship between listening to music and changes in mood states (Ahmed, 2024; Tervaniemi et al., 2021). Additionally, music listening demonstrated positive effects in individuals with Alzheimer’s disease including changes in alertness, joy, and memory performance (Baird & Samson, 2009). The effect of a variety of different types of music on emotional aspects has been noted, with slow-tempo music (60–80 BPM) promoting calmness and mood elevation (Blasco-Magraner et al., 2023). These musical stimulation effects may be linked to the alignment of music tempo with the resting heart rate mediated by the autonomic nervous system and related brain-stem networks, inducing a state of “inner balance” and relaxation (Kume et al., 2017). Furthermore, “pleasing” music induces the release of neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin, contributing to feelings of pleasure and enjoyment (Becker et al., 2023; Chanda & Levitin, 2013; Menon & Levitin, 2005) mediated by limbic circuitry and motivational brain structures such as the nucleus accumbens (Nac). Nac plays a key role in motivationally driven action selection and has a central role in integrating sensory and affective information from different cortical regions that direct attentional resources toward motivationally salient stimuli (Becker et al., 2023; Floresco, 2015).

Multiple neural networks, in both left and right hemispheres, such as in the frontal cortex, auditory-temporal cortex networks, the limbic system, and several areas in the brain stem, are activated significantly while listening to target (motivationally driven) musical stimuli (Reybrouck et al., 2018; Vuust et al., 2022). Primary and associative auditory cortex networks, as well as areas in the prefrontal cortex, amygdala, and cerebellum, are related to different attentional aspects of behavioral regulation, affecting “engagement” during classical music listening. Music can promote neuro-hormonal release into the bloodstream and could impact mental and physical well-being (Daly et al., 2019; Kučikienė & Praninskienė, 2018; Weinberger, 2004). Interestingly, classical music was shown to activate several brain regions related to working memory functioning. Mammarella and colleagues (Mammarella et al., 2007) revealed that listening to Vivaldi’s “Four Seasons” (77–162 BPM) enhanced working memory performance compared to white noise or silence control conditions in healthy adult participants.

Rauscher and colleagues (1993) conducted an experiment in which 36 undergraduate students improved visuospatial thinking on a Stanford-Binet subtest by 8–9 points after listening to Mozart’s Sonata for two pianos (K.448) for 10 min. The effect lasted approximately 12 min, revealing a temporary boost in IQ scores (Rauscher et al., 1993). Rauscher and colleagues examined these effects using various composers, highlighting Mozart’s and Bach’s melodies for their repetitiveness and harmonics. They concluded that music with specific harmonic and repetitive melodic characteristics (e.g., G3 chord), has a positive impact on spatial performance and it also may serve as a therapeutic application to reduce epileptic seizures (Rauscher et al., 1993; Sesso & Sicca, 2020). Rauscher expanded his experiment, by testing the effect of Mozart’s Sonata K.448 on spatial abilities and memory performance (Rauscher et al., 1994). After each session, the participants performed spatial thinking tasks and post-session working memory tasks. Results replicated previous findings, showing significant improvement in spatial-thinking scores in the group that listened to the Mozart’s sonata, while the other conditions did not affect spatial thinking versus control.

One central argument suggests that working memory (WM) processing efficiency following classical music listening, like Mozart’s classical compositions, may arise from shifting the level of comfort and relaxation of the listener. Additionally, certain types of musical patterns can influence higher cognitive functions through the listener’s mental experience, including the activation of motor and emotional brain mechanisms that are recruited significantly during listening in service of representing the musical experience in conscious awareness (Schellenberg et al., 2007). However, Rauscher and colleagues’ (Rauscher et al., 1998) study with animals proposed a different hypothesis, related to engaged emotional brain mechanisms during musical exposure periods. By testing spatial alertness and spatial memory in rats, their study compared the effects of Mozart and Philip Glass’s music, white noise, or silence on their responses to learned visual-spatial stimuli. Rats exposed to Mozart’s music showed significant improvements in maze tasks performance compared to the Glass’s music group. These findings have been consistently supported by results in a meta-analysis study by Trzesniak and colleagues (2024).

Numerous studies have explored the positive effects of Mozart’s Sonata K.448 on several cognitive functions, predominantly, many of these investigations focused on examining executive functions controlled by the prefrontal cortex (PFC), including executive functions such as planning and organization, memory retrieval, working memory (WM), and attentional control. Research indicates improved WM, better long-term memory, enhanced concentration, and enhanced spatial thinking in people who listened to Mozart’s sonata K.448 (Ardi & Fauziyyah, 2018; Limyati et al., 2019; Maghsoudipour et al., 2017; Rauscher, 1994; Schellenberg et al., 2007; Smith et al., 2010). Xing’s (2016a, b) study examined visuospatial functioning in rats using the Hidden-platform Morris water maze (MWM). The results demonstrated increased accuracy and speed in visuospatial memory accompanied by elevated levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor BDNF (related to neural plasticity and synaptic functioning) after exposure to the Mozart K.448 sonata for 12 h daily for 98 days (Xing et al., 2016a, b). These findings suggest a link between increased BDNF levels and improved spatial functions following musical stimulation. A subsequent study in humans by Xing and colleagues (2016a, b) showed enhanced visuospatial function after half-hour daily exposure to the sonata for six consecutive days, supporting the potential role of increased BDNF levels in facilitating enhanced cognitive functioning. However, mixed research designs and different tasks restrict the ability to show consistent effects on both behavioral and neural activity features following music-listening periods in healthy humans.

Functional brain activity can be assessed through various methods, including fMRI (BOLD hemodynamic signal) and by measuring electroencephalography (EEG) that notes raw and quantitative electrical brain-state features. Functional quantitative EEG features are noted by using quantitative electroencephalogram (qEEG) analyses across all clean raw EEG intervals (epochs) denoting mean rhythmic electrical neural activity at specific neural oscillations and their frequency bands (e.g. mean amplitude of neural oscillations at alpha frequency-band, 8–12 Hz), and at specific scalp locations. Event-related qEEG can be used to examine the magnitude of neural oscillations within a specific frequency band under certain scalp-electrodes in response to specific stimuli or events, presented during specific time windows (Müller-Putz, 2020).

In previous event-related qEEG studies, alpha, theta, and beta frequency mean normalized amplitude (e.g. mean power of alpha oscillations) were examined during visual-verbal WM task-related events and during resting-period timed-windows (Gevins et al., 1997; Inguscio et al., 2024; Jacobsen et al., 2020; Onton et al., 2005; Sauseng et al., 2005a, b). Investigations noting changes in neural oscillations during WM tasks revealed increased theta and beta power in medial frontal electrodes during the WM task in healthy people (Gevins et al., 1997; Onton et al., 2005; Pavlov & Kotchoubey, 2020). Sauseng (2005a, b) observed an increase in alpha power across prefrontal cortex areas during tasks with higher WM load. Few studies have characterized neural activity changes and WM improvements accompanied by changes in mood following musical stimulation (Dai & Marshall, 2021). A study investigating the effects of classical music on behavior, especially the effects of Mozart’s slow-tempo sonata K.448 (60–80 BPM) on mental well-being, revealed its relaxation-inducing effects, potentially impacting the ANS. These relaxed mental states modulate heart rate and blood pressure, promoting a sense of calmness and stress reduction concurrent with activation patterns of the parasympathetic system at resting periods. Accordingly, initial findings implied that a short “Mozart effect” exposures can result in lower anxiety levels after two sessions, as measured by the Profile of Mood States (POMS) questionnaire, emphasizing the potential of music-listening to temporarily enhance the capacity for efficient WM storage resource-allocation during mildly stressful situations following music-listening exposures. This adaptation in executive-attention resource allocation is needed during increased cognitive effort periods, such as updating WM targets during WM retention intervals (Ardi & Fauziyyah, 2018; Meiron et al., 2021; Permatasari, 2021). In a study that investigated the therapeutic effect of Mozart’s music on maternal anxiety, Mozart’s music therapy protocols resulted in a moderate decrease in anxiety. Another study focusing on children during stress-inducing conditions (such as during a visit to the dentist) found that listening to Mozart’s sonata K.448 significantly reduced anxiety levels in 76.67% of the children ages 6–12, highlighting its calming effects in various age groups (Ardi & Fauziyyah, 2018; Setiawan et al., 2010). These findings collectively suggest that listening to Mozart’s music, especially the K.448 sonata, positively affects executive cognitive functioning and induces a state of relaxation in both adults and children.

There exists a lack of empirical studies investigating the impact of classical music listening on ongoing neural oscillations across different WM brain states. Thus, the current study aims to examine the effects of listening to Mozart’s K.448 sonata on verbal WM performance, emotional states, and task-related neural oscillatory activity in healthy adults (Ardi & Fauziyyah, 2018; Jacobsen et al., 2020; Manca et al., 2020).

Materials and methods

Particpants

The current study evaluated a sample of 45 healthy adult participants, comprising 23 females and 22 males. All participants reported right-hand dominance. Participants completed a demographic questionnaire, supplying essential personal and health information. Individuals with cognitive disorders (e.g., learning disabilities), and psychiatric and neurological diagnoses were excluded from participation. Participants affirmed their overall health and absence of any medical pathology by collecting personal background data from questionnaires. Age, gender, and educational background were similar across participants indicating academic education levels, above 12 years of education (see Table 1). Participants provided informed consent prior to experimental data collection procedures by signing a document approved by the institutional review board ethics committee. The study received approval from the Ethics Committee of the University. A sample size of 45 participants with a confidence interval 87.3 ± 3.316 of 95% and an effect size of 0.5 (p <.05) was calculated based on a previous study that tested the impact of music on working memory by analyzing participants behavioral data (accuracy and reaction time (RT) and EEG activity (Xu & Sun, 2022).

Design and procedures

The study included a single experimental session lasting 45 min. After signing an informed consent form, participants completed a demographic questionnaire and preliminary baseline behavioral evaluations. Next, music exposure questionnaires were completed by participants before random assignment to different study groups (experimental-passive music-listening, control-resting period without music). After the musical stimulation period, WM task performance was evaluated, and wireless EEG recorded in both study groups (with versus without passive musical stimulation). The integrated EEG-WM system was designed to handle data acquisition and the execution of neuropsychological tasks as was previously described (Jacobsen et al., 2020). The system comprised integrated access to EEG hardware, time-oriented databases, and object-based (non-SQL) data schemes and features a Python-based web user interface, allowing for offline data exploration and analysis, and task programming on top of synchronized EEG recording and users’ performance monitoring.

To assess basic cognitive functioning at baseline, all participants underwent the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) questionnaire (Folstein et al., 1975), yielding scores consistently above 25, indicative of a normal range of basic cognitive functioning (M = 29.2, SD = 1.014). Subsequently, participants were randomly assigned either the experimental group (n = 23) exposed to Mozart’s sonata K. 448 for 9 min and 26 s, or to the control group (n = 22). All were instructed to remain seated for an equivalent duration in an isolated room, without musical stimulation (Rauscher et al., 1994; Smith et al., 2010). Participants were allocated to groups based on responses to a musical preferences questionnaire across various genres.

The experimental group was exposed to Mozart’s sonata K. 448, and the control group sat in silence in the same room for the same duration as the experimental group participants. The experimental group listened to the sonata through laptop speakers (15.6 inches, played at maximum volume, 55 dB, without headphones) for 9 min and 26 s. The musical section employed in the experimental group was the slow rhythm Andante movement (72–76 BPM), performed by Ingrid Haebler and Ludwig Hoffmann, spanning from 8:23 to 17:49 in the original musical recording. Conversely, the control group sat on a chair in an isolated room for 9 min and 27 s, without musical stimulation, adhering to established protocols in similar experiments. Participants were instructed to refrain from verbal communication or engaging in any activities during the control condition. Both groups completed a brief version of the Profile of Mood States (POMS) questionnaire. Immediately after the mood questionnaire completion, participants performed a two-back task (verbal WM task), evaluating visual-verbal working memory performance (RT and accuracy). Concurrently, mean power across various frequency ranges under 14 electrodes (mean spectral density power of theta, alpha, beta, and gamma frequency bands) was recorded.

Pre-musical exposure

Musical exposure/preference questionnaire

To evaluate previous music exposure effects, the participants completed a musical exposure questionnaire before being divided into groups. The questionnaire included seven different music genres that are common among the Israeli population, and participants rated their exposure time to each genre in percentages from 0 to 100% in 10% increments. The questionnaire facilitated sample selection that confirmed equal distribution of musical preference and deduced preferences between the two groups to limit the effects of personal music exposure variability (Honing & Ladinig, 2009).

Post musical exposure

Profile of mood states (POMS) questionnaire

Following the musical listening period or silent-sitting, participants completed the Profile of Mood States (POMS) questionnaire. The POMS is widely used in clinical and research settings to track fluctuations in mood over time or in response to experimental manipulations (Ajmal et al., 2022; Justeau et al., 2021; Reynoso-Sánchez et al., 2021). Originating from McNair (McNair et al., 1971), the questionnaire was translated into Hebrew and condensed to 28 items by Netz (Cronbach’s α = 0.89) whose study population was comparable with the current sample (Netz et al., 2005). The translated version underwent rigorous validation, aligning with the methodology detailed in Yeun (2006). The translation process consisted of two stages: initial translation by a native Hebrew and English speaker, scrutinizing linguistic and structural elements, followed by reverse translation by another bilingual translator (Hebrew and English). A third native English speaker then compared the translated version with the original English instrument, confirming congruence. The questionnaire was designed to assess participants’ moods immediately after exposure to either Mozart’s sonata or silence, including 28 sentences (scale items), each rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (“Not at all”) to 4 (“Extremely”). The original questionnaire consisted of 65 items assessing six mood dimensions: Tension-Anxiety, Depression-Dejection, Anger-Hostility, Vigor-Activity, Fatigue-Inertia, and Confusion-Bewilderment (McNair et al., 1971). Participants rated each item on a five-point scale, reflecting their mood at the moment of filling out the questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of five factors and all the items were divided into the following emotional factors: “Vigor” (items 5, 7, 9, 17, 24, 26, 2), “Fatigue” (items 3, 12, 18, 23, 28), “Tension” (items 1, 10, 19), “Depression” (items 4, 8, 11, 15, 16, 21, 22) and “Anger” (items 2, 6, 13, 14, 20, 25). An elevated “Vigor” factor score signified a more positive mood. Conversely, in other factors, heightened scores indicated a more negative mood. In our study, Cronbach’s α coefficients ranged between 0.64 and 0.92.

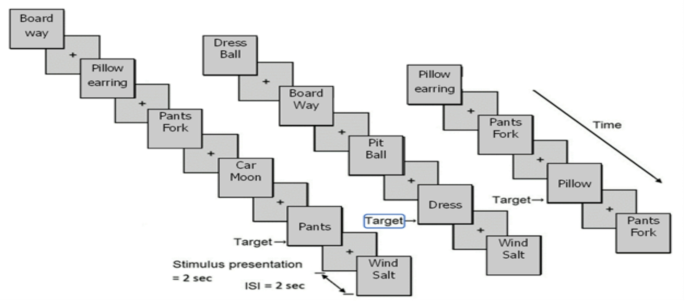

Working memory task

After questionnaire completion, participants engaged in a computerized neurocognitive task assessing working memory (WM) performance (Meiron et al., 2021). The n-back task is a widely used neuropsychological test that assesses temporary memory storage and WM processing (Inguscio et al., 2024; Jansma et al., 2000; Lamichhane et al., 2020; Owen et al., 2005). During standard versions of the task, participants are presented with a sequence of stimuli (for example, letters or numbers) and they are required to encode and temporarily store them and indicate whether the current stimulus matches a stimulus that was presented n steps earlier in the sequence. The participant’s performance relies to a large extent on continuous updating of the contents of working memory across 2000 ms intervals. The n-back task allows manipulation of different working memory loads according to the number of backward steps (1-back versus 2-back) and it has been established as a reliable way to test working memory across research paradigms (Chen et al., 2024; Meiron et al., 2021; Mercado et al., 2022; Nikolin et al., 2021). Assessing verbal working memory in this way can reliably examine interventional effects of music on executive functioning. Considering the central roles of working memory, it is crucial to investigate new stimulation modalities that can enhance VWM performance. The current n-Back task presented visual verbal stimuli (see verbal n-Back task, Fig. 1) on a computer screen, and participants were instructed to study a stream of word pairs interspaced by fixations (2 s time window). Following two to five presentations of word pairs (study displays), participants were exposed to a single word (2 s time window) that either appeared or did not appear in earlier displays (i.e., 2-back task). The objective of the task, as explained to participants, was to determine if the single word was within a “target” word pair presented two previous study displays (see Fig. 1, “pants” and “pillow” target words). In the event of target recognition, participants were instructed to press a key (Go response), if the word was not from two-back event participants were instructed to avoid responding (No-Go response). The computer recorded participants’ mean RTs and mean accuracy of go-responses and correct no-go-responses (Meiron & Lavidor, 2013). (e.g., correctly identifying a single word that appeared within a pair of words from two study displays ago, see Fig. 1).

The single-word stimulus-presentations (target words) were presented unexpectedly in the center of the screen during response intervals (2000 ms). The ongoing presentation of study displays (paired words) was separated by 2000 ms interstimulus intervals (ISIs) featuring a white screen presentation with a black (+) visual fixation stimulus at the center of the screen. During ISIs, participants were oriented to focus on the visual fixation while temporarily retaining the pairs of words they recently encoded. In response intervals where the target word served as a “non-target” distractor (No-go target, see “dress” word, Fig. 1), participants were instructed to refrain from responding. The task included various levels of working memory load (Meiron & Lavidor, 2013). Participants were instructed to respond as fast as possible when identifying the target stimulus during the response intervals (response-display). Before the working memory task phase, participants underwent a short training period to verify comprehension of task objectives and stimuli (7 different trials during the training phase), after which the researcher initiated the test phase including four rounds of 12 different trials per round, totaling 48 WM task trials (Meiron et al., 2021).

EEG acquisition and analysis

During the performance of the verbal n-Back task, neural oscillatory activity within different frequency bands were recorded from using a wireless EEG acquisition and analysis system (Emotiv, USA). The EEG system transformed (using Fourier transforms) raw to quantitative EEG activity online (mean normalized amplitude of neural oscillations at frequency bands of between 4 and 45 Hz, during different WM task time windows) that quantified the mean amplitude of neural oscillations in different frequency bands (such as mean alpha or gamma power under specific electrodes) during the WM-task time-windows and resting periods intervening between the WM trial blocks. The EMOTIV EEG system (Emotiv EPOC+, San Francisco, USA) included 14 EEG wireless electrodes and two additional lateral-parietal reference electrodes, located according to the international 10–20 system. This Emotiv EEG system has been consistently used to reliably record functional neural responses with ‘reliability similar to a research-grade system that record with leads and gel-electrodes (de Lissa et al., 2015). The internal sampling rate of the EEG signal used by the system was 2048 Hz. The raw EEG processing removed external noise and harmonic frequencies. In particular, 50 Hz notch-filter and frequencies higher than 64 Hz were automatically removed, and EEG data was down-sampled to 128 Hz before event-related qEEG analysis. EEG resolution was 14 bits with a sensitivity of 1 LSB = 0.51/µV. Noise cancellation procedures were employed following the methods described by Meiron and associates (2021).

During the WM task and resting intervals, mean frequency power was extracted by averaging all clean 1.5-second WM-task EEG intervals from pre-retrieval events, task-related two-second intervals (representing storage and encoding time windows of WM events, averaging all consecutive 1000ms epochs from four different WM task rounds), and during 30 s resting periods presented between the four different WM task rounds (2. The online bandpass filter was 0.16–43 Hz, with a dynamic range of 8400 µV. Automatic online FFT analysis was acquired in units of Power Spectral Density (PSD), reflecting FFT absolute-squared spectral power in a certain frequency range. Thus, as indicated, the current study employed a dedicated integrative EEG-WM system that combined an “online” WM-EEG recording (and FFT for qEEG analysis) (Jacobsen et al., 2020). Mean power (mean PSDs) in different frequency ranges (mean theta, alpha, beta, and gamma power) were calculated under each electrode separately for each participant at different WM and resting time intervals. Because the ongoing neural-oscillatory activity recorded is not time-locked and is not reflective of induced or evoked power changes relative to a preceding event, automatic analysis of the mean PSD was extracted from averaging frequency-specific power values from different WM-specific time-windows and during resting time-windows reflecting a single-trial analysis modality of qEEG activity at specific functional time windows (e.g., during specific working memory events and rest). Noted qEEG analysis frequency bands employed were theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–12 Hz), low beta (12–16 Hz) and high beta (16–25 Hz).

Results

A series of Mann-Whitney tests for independent samples were conducted to assess potential disparities in musical preference ratings between study groups. There were no significant differences in the mean ratings of musical preference between groups. Further examination revealed no discernible distinctions in musical inclination among groups across all musical preference categories (p >.05). To verify that WM performance was independent of baseline MMSE scores and demographic variables, Pearson correlations were conducted revealing no significant relationships between WM performance and baseline variables (see Table 2).

Behavioral results

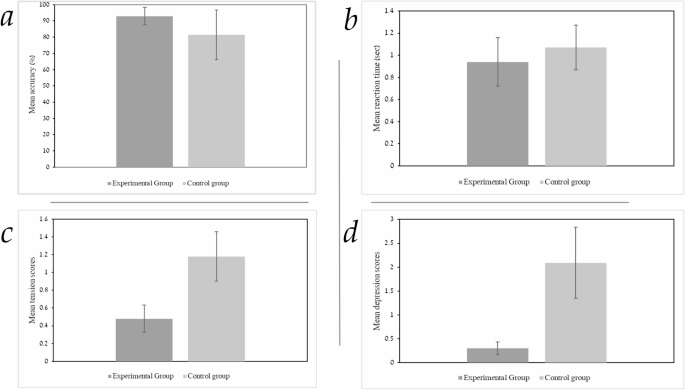

To examine potential differences in working memory performance, between the individuals exposed to Mozart’s sonata K.448 and those who were not, student t-tests revealed significant differences in WM accuracy (percentage of correct responses) between the groups, with significantly higher accuracy scores (M = 92.93, SD = 5.32) in the experimental group, (t = −3.33, df, 25.80, p <.003) versus the control group accuracy scores (M = 81.43, SD = 15.30). (as shown in Fig. 2a). The effect size, calculated using Cohen’s d, was 1.01, indicating a large effect. Student t-tests indicated a significant difference in RTs between the experimental and control groups (see Figure. 2b). The experimental group demonstrated faster RTs (M = 0.94, SD = 0.22) for accurate WM responses compared to the control group (M = 1.07, SD = 0.20), t = 2.03, df, 43, p <.02). The effect size, calculated using Cohen’s d, was 0.6, indicating a medium effect size. To examine group differences in mood indices between the experimental group exposed to Mozart’s sonata K. 448 and the control group, a one-way MANOVA - was employed. The analysis examined the effect on five mood variables from the POMS questionnaire, namely vigor, fatigue, tension, depression, and anger. No significant differences were found across all mood variables (F(5,39) = 1.62, p <.05, ƞ2 =0.17). However, post hoc t-tests indicated significant group differences in the level of tension and depression. The experimental group displayed lower levels of tension and lower levels of depression in comparison to the control group.

a WM accuracy as a function group. The Y-axis represents the mean accuracy of the task in percentages and the X-axis represents the study groups. Statistically significant results, p <.01. The error bars represent one SD. b RT as a function of group. The experimental group demonstrated faster RTs of correct WM responses versus the control group. The Y-axis represents the mean RT in the task in seconds and the X-axis represents the study groups. Statistically significant results, p <.05. The error bars represent one SD. c Tension index according to the POMS questionnaire in the two study groups. The Y-axis represents the mean tension index according to the POMS questionnaire and the X-axis represents the study groups. Statistically significant results, p <.05. The error bars in each column represent one standard error. d Depression index according to the POMS questionnaire in the two study groups. The Y-axis represents the mean Depression index according to the POMS questionnaire and the X-axis represents the study groups. Statistically significant results, p <.05. The error bars in each column represent one standard error

qEEG

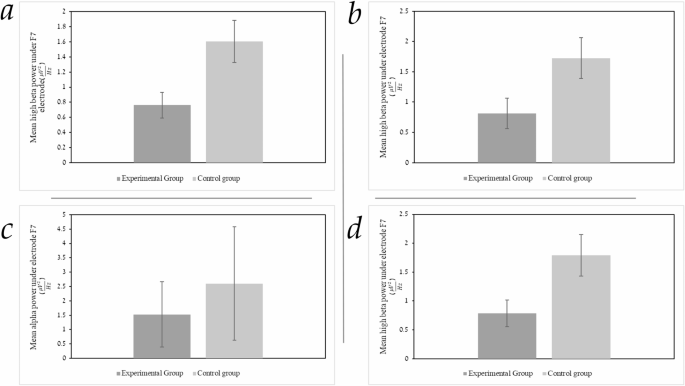

To assess our hypothesis regarding differences in mean frequency power during the n-back task between study groups (at each electrode of interest during a specific time interval), student t-tests were conducted. The analysis incorporated mean frequency-band power in three frequency ranges from three different task phases: rest, retention (fixation), and encoding (word-pairs) intervals. The analysis focused on averaging the mean power at each frequency (e.g., mean amplitude of the alpha oscillations) from target electrodes F7, F8, P7, and P8. The frequency band ranges examined were theta (4–8 Hz), alpha (8–13 Hz), low beta (12–16 Hz), and high beta (16–25 Hz) during the three different task conditions (rest, encoding, and retention intervals). A significant difference between groups was found in high-beta power under left prefrontal electrode F7 during rest, t = 2.56, df, 34.72 p <.01. Mean high-beta power at rest under electrode F7 was significantly lower in the experimental group (M = 0.76, SD = 0.79) compared to the control group (M = 1.60, SD = 1.31). The effect size, calculated using Cohen’s d, was 0.77, indicating a medium effect. A significant difference between groups in high-beta power during the “retention interval” (fixation) was found as well, under electrode F7, t = 2.16, df, 38.85, p <.03). Mean high-beta power during “retention-interval” under electrode F7 was also lower in the experimental group (M = 0.81, SD = 1.18) compared to the control group (M = 1.72, SD = 1.58). The effect size, calculated using Cohen’s d, was 0.65, indicating a medium effect. A significant difference between groups in mean alpha power during “encoding” time intervals was found, under electrode F7, (t = 2.13, df,39, p <.03). Alpha power during “encoding” under electrode F7 was lower in the experimental group (M = 1.52, SD = 1.14) compared to the control group (M = 2.60, SD = 1.97). The effect size, calculated using Cohen’s d, was 0.66, indicating a medium effect. A significant difference between groups in high beta power during “encoding” time intervals was found, under electrode F7, (t = 2.35, df, 35.86, p <.02). Thus, mean high-beta power during “encoding” under the F7 electrode was lower in the experimental group (M = 0.78, SD = 1.08) compared to the control group (M = 1.79, SD = 1.68). The effect size, calculated using Cohen’s d, was 0.70, indicating a medium effect-size (Figs. 3 and 4).

a Mean power of high beta at “rest” under electrode F7 in the experimental group versus the control group. The Y-axis represents the mean power of high beta at rest under electrode F7 in \(\:\frac{\mu\:{V}^{2}}{Hz}\) and the X-axis represents the study groups. Statistically significant results, p <.05. The error bars in each column represent one standard error. b Mean power of high beta during “retention” intervals under electrode F7 in both the experimental group and control group. The Y-axis represents the mean high beta power during “retention intervals” under electrode F7 in \(\:\frac{\mu\:{V}^{2}}{Hz}\) and the X-axis represents the study groups. Statistically significant results, p <.05. The error bars in each column represent one standard error. c Mean power of alpha during “encoding” under electrode F7 in both the experimental group and control group. The Y-axis represents the mean alpha power during “encoding” under electrode F7 in \(\:\frac{\mu\:{V}^{2}}{Hz}\) and the X-axis represents the study groups. Statistically significant results, p <.05. The error bars in each column represent one SD. d Mean power of high beta during “encoding” under electrode F7 in both the experimental group and control group. The Y-axis represents the mean high beta power during “encoding” under electrode F7 in \(\:\frac{\mu\:{V}^{2}}{Hz}\) and the X-axis represents the study groups. Statistically significant results, p <.05. The error bars in each column represent one standard error

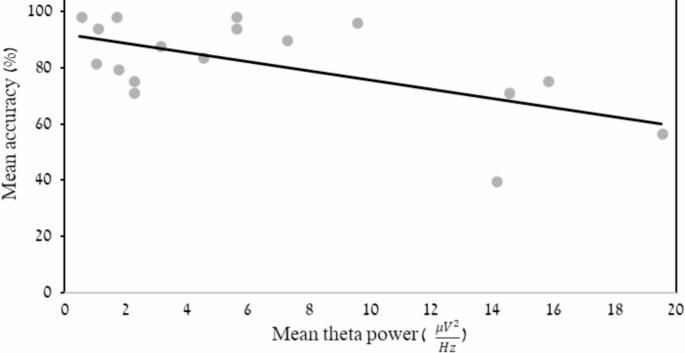

A stepwise hierarchical regression was performed to test which frequency-band activity (e.g. mean alpha power under F7 electrode during encoding) in the right frontal and right parietal electrodes statistically predicted the WM accuracy scores. In the first block of the regression model, the background variables age, years of education, and MMSE score were entered. In the second block, the variables F8 alpha power at rest, P8 theta power at “retention” intervals, and F8 alpha power during “encoding” were entered as predictors in the regression model. The regression model indicated that the percentage of shared variance was 19.1% (R Square = 0.19) and the regression model was found to be statistically significant (R =.43, F(1, 33) = 7.8, p =.009). The independent variable that was found to be a significant predictor in the regression model was mean theta-power under right parietal P8 electrode during the WM “retention” intervals.

Relationship between mean working memory accuracy and mean theta power under right parietal P8 electrode during WM “retention” intervals in the control group only. The X-axis represents the mean theta power. The Y-axis represents the mean accuracy rate in the working memory task

Discussion

The present study aimed to evaluate the effects of listening to Mozart’s Sonata K. 448 on verbal WM, mood, and functional EEG activity. Our primary objective was to determine whether passive listening to Mozart’s Sonata K. 448 could temporarily enhance working memory performance, modify emotional state levels, and modulate brain activity as measured by event-related quantitative-EEG (qEEG). The results confirmed our hypotheses, showing that participants who listened to the sonata exhibited improved WM performance and reported lower stress and depression levels compared to the control group. Additionally, qEEG analysis revealed significant differences between the groups acrooss different task-related intervals, including lower mean beta power under the left prefrontal F7 electrode during rest, encoding, and memory retention intervals, and higher frontal alpha power during encoding intervals in the experimental group versus -the control group. These findings suggest that music in the form of Mozart’s Sonata K. 448 can positively influence WM functioning and emotional states in humans potentially offering valuable applications in in different therapeutic settings. These results tentatively support the hypothesis that a 9:26 min exposure to Mozart’s sonata K. 448 temporarily enhances visual-verbal WM performance in healthy people (Meiron & Lavidor, 2013; Rideout & Laubach, 1996; Sarnthein et al., 1997).

Our findings align well with previous investigations that evaluated the impact of listening to Mozart’s sonata K. 448 on working memory. Rauscher et al. (1993) observed an improvement in a visuospatial thinking subtest of the Stanford-Binet intelligence scale after a brief 10-minute musical exposure. Numerous studies have successfully replicated and extended these behavioral benefits (Ardi & Fauziyyah, 2018; Taylor & Rowe, 2012; Xing et al., 2016a, b). Our results partially support previous findings related to enhanced short- and long-term memory performance following musical stimulation periods (Ardi & Fauziyyah, 2018; Limyati et al., 2019; Maghsoudipour et al., 2017). In a study by Mammarella et al. (2007), classical music, specifically, a group that listened to Vivaldi’s musical pieces, outperformed a group in “exposure to white noise” condition resulting in better visual memory performance.

Our predictions regarding the positive impact of music listening on mood were partially supported. Findings revealed lower stress and depression scores in the experimental group compared to the control group. This between-group effect would need to be replicated in larger samples using neurocognitive tasks that are more sensitive to subconscious emotional responses (e.g., emotional Stroop task) associated with activity in emotional-regulation brain mechanisms (Freggens, 2014). Replicating these effects in people suffering from anxiety and depression would provide additional insights into the specific brain mechanisms and behaviors associated with musical stimulation treatment-effects in humans and in people with different psychopathological conditions associated with WM dysfunction (e.g. major depressive disorder).

Listening to Mozart’s sonata K. 448 for 9:26 min seems to positively impact the mood of individuals, which is likely to be mediated by the parasympathetic system and limbic system neurohormonal activity changes. The chosen tempo in the current investigation (60–80 BPM) aligns with studies on music’s positive effects on cardiovascular indicators (Ardi & Fauziyyah, 2018; Chan et al., 2009; Darki et al., 2022). Darki et al. (2022) observed that classical music at a slow tempo (69 BPM) promotes a calm state by reducing heart rate and blood pressure, attributed to its influence on the ANS, particularly the vagus nerve. Our study supports the idea that listening to Mozart’s sonata K. 448 induces a positive mood versus the control condition, however, it also increased executive attention functioning, associated with increased prefrontal cortex involvement and improved WM performance (Arnsten & Rubia, 2012; Tyng et al., 2017).

In the current study, listening to the slow section of Mozart’s sonata K. 448 for 9:26 min resulted in lower high beta power (at rest, retention, and encoding intervals) under electrode F7 and lower alpha power during encoding under the same left frontal electrode in the experimental group in comparison to the control group. Studies measuring frequency-power in specific frequency-bands during verbal working memory tasks have consistently reported increased alpha and beta power under frontal electrodes such as F7 and F8 during encoding and retention time-windows versus other electrode locations. This effect was interpreted as enhanced frontal alpha inhibition within fronto-partial networks. This type of increased alpha synchronization facilitates functional alpha inhibition of irrelevant information and retrieval of target information stored in working memory, optimizing performance during executive attention tasks (Gevins et al., 1997; Jacobsen et al., 2020; Meiron et al., 2021; Onton et al., 2005; Sauseng et al., 2005a, b). Playing music with a slow tempo (60–80 BPM), was found to increase mean alpha power during rest. Increased alpha-mediated functional inhibition positively impacts attention mechanisms and higher-order cognitive functions, including working memory (Meiron et al., 2021). Notably, during a working memory task, an increase in frontal-parietal theta power during increased WM load was observed, accompanied by a decrease in mean alpha and beta power in frontal and parietal regions. This decrease in alpha/beta power correlates with successful performance in working memory tasks (Gupta & Gupta, 2005; Lundqvist et al., 2011; Tsoneva et al., 2011). Therefore, our findings partially support the idea that decreased alpha and high beta power under left prefrontal electrodes during resting and retention intervals may reflect less prefrontal functional inhibition and increased prefrontal excitatory network activation, which is associated with better WM accuracy rates and faster RT’s following the musical intervention period in the experimental group. More so, in support of hypothesized reduced levels of lateral prefrontal functional inhibition in the experimental group, improved emotional regulation (as observed in the current study) is likely a result of increased activation in proximal interconnected PFC networks in medial-ventral or fronto-orbital cortical areas involved in emotionally guided responses (Arnsten & Rubia, 2012).

The current investigation allowed the evaluation of participants’ functional neural activity features while engaging in a cognitively demanding task following musical stimulation. The observed decrease in alpha power under the left prefrontal electrode during encoding in the experimental group versus control group suggests a more effective allocation of executive attention prefrontal cortex networks at left frontoparietal cortical global network regions leading to enhanced working memory task performance in the experimental group (Manza et al., 2014). To support the role of left prefrontal function inhibition during WM retention intervals, further investigation of the relationship between changes in alpha activity before and after the musical intervention within each group over different periods is warranted (Gupta & Gupta, 2005; Meiron et al., 2021). In relatively demanding executive-attention tasks, decreased beta power and decreased alpha power under frontal target electrodes (F7, F8), during encoding and retention time windows were associated with better WM function. Uncontrolled beta-power elevation during retention or resting states may signal excessive global-network involvement, potentially hindering prefrontal cortex executive control of WM. Beta power changes are essential for allocating cognitive resources and synchronizing cortical sensory-associative networks and emotional regulation mechanisms that modulate prefrontal activity during WM retention intervals (da Silva, 1991; Jacobsen et al., 2020; Liang et al., 2021). As observed in previous studies and in the current study, under cognitively demanding WM tasks, a reduction in mean beta power along with alpha power reduction in the experimental group compared to the control group was accompanied by a significant improvement in accuracy and RTs in the WM task. Our results indicated distinctive modulated neural activity under prefrontal electrode sites, with music versus no-music condition. This finding putatively supports the idea that enhanced WM performance following classical musical stimulation may be mediated by fronto-parietal network activity and increased prefrontal cortex excitability (Meiron & Lavidor, 2013).

In the three WM task conditions (rest, retention, and encoding), high beta power was consistently lower in the experimental group after listening to a Mozart sonata, and this effect was accompanied by affective-behavioral effects related to “cold” (WM scores) and “hot” (emotional ratings) prefrontal cortex functions. In accordance, our findings suggest that the music-listening may have induced a more relaxed brain state. This effect could have facilitated the allocation of resources needed for learning, implied by the parallel reduction of high beta frquency and gamma frequency power. Learning may manifest as the proper application of optimal strategies to achieve task goals under higher attentional demands, possibly utilizing frontal-parietal cortex resources without requiring a substantial rise in high-beta or gamma activity. Conversely, higher high-beta power in the control group across the different task conditions suggests a greater need for cognitive resources, likely reflected in their lower WM performance. Differences in high-beta power between the experimental and control groups may indirectly support the relationship between a positive emotional state and increased executive attention control. The reduced attentional demands across parietal-frontal cortex WM resources in the experimental condition reflected by lower frontal alpha power suggests a potential impact of music-listening on the default mode network (DMN), a global brain system involving interconnected activity in various areas like the bilateral angular gyri, medial prefrontal cortex and posterior cingulate cortex. The DMN is typically activated during resting periods, daydreaming, and reflective thinking and is associated with increased frontal alpha inhibition, however, DMN activity may be temporarily inhibited through reduction in frontal alpha inhibition during WM retention intervals, underlying goal-directed behavior, and disengagement from DMN activity (Vatansever et al., 2017).

Interestingly, in the control group, lower theta power under right parietal P8 electrodes during retention intervals was linked to higher WM accuracy. This relationship was not observed in the experimental group, suggesting that musical stimulation may have influenced the recruitment of fronto-parietal theta activity, temporarily suppressing the magnitude of phase-coupled beta activity. The absence of this relationship in the experimental group may be attributed to increased prefrontal cortical arousal in the experimental group versus the control group. These findings are intriguing since theta power dynamics in cognitively challenging states (versus resting states) may reflect active shifts in “directed-attention” brain states influenced by DMN activation involving medial PFC activity, impacting resource allocation to sustain working memory capacity and prefrontal cortex functional control of target-information storage (Koshino et al., 2014). Theta power dynamics under frontal-parietal electrodes during WM retention may be related to changes in functional connectivity within frontal-parietal networks integrating multimodal information stored in different cortical memory networks activated at pre-retrieval WM intervals (Meiron et al., 2021). WM-related changes in prefrontal theta synchronization aligns with findings in a study by Bender et al. (2019), where noninvasive electrical oscillatory stimulation of 4 Hz (within the lower theta frequency band range) targeting parietal cortex regions improved visual and working memory functioning. Kawasaki et al. (2010) indirectly supports the current findings, indicating that increased right frontal theta activity may be associated with WM resource allocation within prefrontal-parietal networks. Unlike the control group, in the experimental group listening to Mozart’s sonata may have shifted or “down-regulated” right parietal theta activity involvement to sustain better task accuracy. In an fMRI study, during a WM task, faster RTs were associated with higher activation in the right anterior part of the DMN network at rest, and reduced activation during the WM task. This finding is consistent with our findings indicating that music-listening may have resulted in a more stable left anterior DMN network activity and efficient executive network top-down modulation of target information reflected in improved WM performance (Koshino et al., 2014).

The current findings demonstrated that short, passive listening periods of Mozart’s Sonata K.448 can have a temporary rewarding impact on both executive cognitive control and emotional states in humans. Remarkably, these differences were observed after just a single listening session, highlighting that one relatively brief exposure to music could be sufficient to elicit significant cognitive and emotional benefits, without the need for multiple and long-period exposures. These findings have substantial practical implications, particularly in educational and therapeutic settings. In educational systems, integrating musical interventions, such as listening to classical compositions, can enhance students’ working memory, thereby improving their capacity to retain and manipulate information, which is critical for learning and academic achievement. Additionally, the mood-enhancing effects observed—such as reduced stress and depression levels suggest that such musical exposures could foster a more positive and conducive learning environment (Vigl et al., 2023). Therapeutically, the observed modulation of brain activity and improvements in mood highlight the potential for using Mozart’s Sonata K.448 as a non-invasive treatment intervention to support mental health recovery in an array of clinical populations suffering from reduced emotional regulation and compromised WM functioning, such as major depressive disorder (MDD) patients.

Limitations of the study

The relatively small sample size, and a relatively homogeneous demographic population hinder the ability to generalize the current findings to the general population. At the same time, the length of the study was relatively short, and the between-group effect was tested only after the musical stimulation. There is a need for a long-term longitudinal study examining the consistency of the effect on the listener’s cognitive abilities and brain activity over several consecutive sessions versus baseline. Another limitation is the fact that we used only one type of musical stimuli. It would be prudent to assess brain activity and WM functioning over follow-up periods (one to four weeks after music listening) and compare the long-term effects of different types of music on WM performance and mood. It is worth noting that the evaluation of the mood in the current study was completed subjectively by using personal-report questionnaires, thus current findings should be further tested and supported with additional physiological objective indicators such as measurements of electrodermal activity or heart rate variability (HRV) before and after the musical stimulation. Another limitation in the current study is the lack of a a comparison group displaying a specific PFC-related brain-disorder (e.g. MDD, schizophrenia) related to working memory impairments and prefrontal-parietal hypofunction (Meiron et al., 2022). Introducing a clinically defined group with working memory deficits, such as MDD patients, would enhance our understanding of the brain mechanisms underlying prefrontal cortex-mediated WM deficits in these “hypo-frontal” disorders and may assist in objectively in quantifying clinical symptom alleviation, and improved WM capacity. However, the current findings, if replicated in larger cross-cultural sample, could also represent a diverse healthy population, mirroring the variability in WM functioning and related neural activity in the general adult population (Scharinger et al., 2017). One weakness in the current study paradigm is the absence of a pre-exposure measurement to evaluate changes in working memory and functional brain states over time, and it is necessary to conduct a follow-up study that will examine pre- to post-musical stimulation effects to confirm that all participants had similar baseline performance, prior to music listening intervention. However, it is worth noting that repetitive consecutive WM tasks are associated with increased cognitive fatigue and participants are more familiar with the cognitive task when retesting, affecting differentially memory storage mechanisms, such as long-term memory. Thus, future investigations should include an acoustic “insulated” condition to avoid different levels of sensory distractibility. In addition, the control group was not presented with a predefined stimulus that could be controlled and compared effectively with the experimental condition, so it would be appropriate to examine auditory stimulus-specific control-conditions in future studies in which a control auditory stimulus is presented that will engage the attention participants in the control group (such as an audio-book), so that they will not attain a state of boredom, or mind-wandering.

Conclusion

In support of our hypothesis, listening to Mozart’s sonata K. 448 was significantly associated with augmented functional brain states and improved WM performance in healthy adults. In the control group, a distinct correlation between right parietal theta power and WM accuracy was apparent, emphasizing a significant contribution of theta activity under the right parietal electrode P8 to WM functioning in the unaffected control group. Future research is crucial for developing a more comprehensive understanding of musical stimulation effects on WM-related neural oscillations, potentially integrating the current paradigm with the application of transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) at right parietal locations. Exploring narrower younger age ranges and evaluating treatment effects of music in different neurodevelopmental populations (e.g., ADHD, autistic spectrum disorder), would illuminate temporary and long-term changes in functional brain activity. This type of musical-listening intervention in different life stages particularly during critical developmental stages of PFC maturation from adolescence to adulthood could aid in suppressing or alleviating PFC-related psychiatric-symptoms in adolescent MDD and prodromal schizophrenia patients.

Data availability

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

References

Ahmed, A. M. M. (2024). The impact of music on mood: Descriptive observations of listening experiences and their effect on mental health. IOASD Journal of Medical and Pharmaceutical Sciences, 1(1), 103–107.

Ajmal, A., Aldabbas, H., Amin, R., Ibrar, S., Alouffi, B., & Gheisari, M. (2022). Retracted: Stress-Relieving video game and its effects: A POMS case study. Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience, 2022(1), 4239536. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4239536

Ankri, Y. L., Braw, Y. C., & Meiron, O. (2023). Stress and right prefrontal transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS) interactive effects on visual working memory and learning. Brain Sciences, 13(12), 1642. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13121642

Ardi, Z., & Fauziyyah, S. A. (2018). The exploration classical music contribution to improve children’s memory abilities. Educational Guidance and Counseling Development Journal, 1(2), 52–60. https://doi.org/10.24014/egcdj.v1i2.5609

Arnsten, A. F., & Rubia, K. (2012). Neurobiological circuits regulating attention, cognitive control, motivation, and emotion: Disruptions in neurodevelopmental psychiatric disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 51(4), 356–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2012.01.008

Baird, A., & Samson, S. (2009). Memory for music in Alzheimer’s disease: Unforgettable?? Neuropsychology Review, 19(1), 85–101. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-009-9085-2

Becker, M., Yu, Y., & Cabeza, R. (2023). The influence of insight on risky decision making and nucleus accumbens activation. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 17159. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-44293-2

Bender, M., Romei, V., & Sauseng, P. (2019). Slow theta tACS of the right parietal cortex enhances contralateral visual working memory capacity. Brain topography, 32, 477–481. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10548-019-00702-2

Blasco-Magraner, J. S., Bernabé-Valero, G., Marín-Liébana, P., & Botella-Nicolás, A. M. (2023). Changing positive and negative affects through music experiences: A study with university students. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 76. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01110-9

Castillo-Pérez, S., Gómez-Pérez, V., Velasco, M. C., Pérez-Campos, E., & Mayoral, M. A. (2010). Effects of music therapy on depression compared with psychotherapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 37(5), 387–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2010.07.001

Chan, M. F., Chan, E. A., Mok, E., & Kwan Tse, F. Y. (2009). Effect of music on depression level and physiological responses in community-based older adults. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 18(4), 285–294. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2009.00614.x

Chanda, M. L., & Levitin, D. J. (2013). The neurochemistry of music. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 17(4), 179–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2013.02.007

Chen, D. Y., Di, X., Amaya, N., Sun, H., Pal, S., & Biswal, B. B. (2024). Brain activation during the N-back working memory task in individuals with spinal cord injury: A functional near-infrared spectroscopy study. BioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2024.02.09.579655

da Silva, F. L. (1991). Neural mechanisms underlying brain waves: From neural membranes to networks. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology, 79(2), 81–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/0013-4694(91)90044-5

Dai, M., & Marshall, N. A. (2021). Exploring the relationship between music and children’s cognitive ability exploring the relationship between music and children’s cognitive ability. Problems in Music Pedagogy, 20(1), 59–70.

Daly, I., Williams, D., Hwang, F., Kirke, A., Miranda, E. R., & Nasuto, S. J. (2019). Electroencephalography reflects the activity of sub-cortical brain regions during approach-withdrawal behaviour while listening to music. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-45105-2

Darki, C., Riley, J., Dadabhoy, D. P., Darki, A., & Garetto, J. (2022). The effect of classical music on heart rate, blood pressure, and mood. Cureus, 14(7). https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.27348

de Lissa, P., Sörensen, S., Badcock, N., Thie, J., & McArthur, G. (2015). Measuring the face- sensitive N170 with A gaming EEG system: A validation study. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 253, 47–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2015.05.025

Delleli, S., Ouergui, I., Ballmann, C. G., Messaoudi, H., Trabelsi, K., Ardigò, L. P., & Chtourou, H. (2023). The effects of pre-task music on exercise performance and associated psycho-physiological responses: A systematic review with multilevel meta-analysis of controlled studies. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1293783. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1293783

Dingle, G. A., Sharman, L. S., Bauer, Z., Beckman, E., Broughton, M., Bunzli, E., & Wright, O. R. L. (2021). How do music activities affect health and well-being? A scoping review of studies examining psychosocial mechanisms. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 713818. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.713818

Floresco, S. B. (2015). The nucleus accumbens: An interface between cognition, emotion, And action. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 25–52. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115159

Folstein, M. F., Folstein, S. E., & McHugh, P. R. (1975). Mini-mental state. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 12(3), 189–198. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6

Freggens, M. (2014). The effect of music type on emotion regulation: An emotional-Stroop experiment. https://doi.org/10.57709/6909562

Gevins, A., Smith, M. E., McEvoy, L., & Yu, D. (1997). High-resolution EEG mapping of cortical activation related to working memory: Effects of task difficulty, type of processing, and practice. Cerebral Cortex (New York NY: 1991), 7(4), 374–385. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/7.4.374

Giannouli, V., Yordanova, J., & Kolev, V. (2024). Can brief listening to Mozart’s music improve visual working memory?? An update on the role of cognitive and emotional factors. Journal of Intelligence, 12(6), 54. https://doi.org/10.3390/jintelligence12060054

Groarke, J. M., Groarke, A., Hogan, M. J., Costello, L., & Lynch, D. (2020). Does listening to music regulate negative affect in a stressful situation? Examining the effects of self-selected and researcher‐selected music using both silent and active controls. Applied Psychology: Health and Well‐Being, 12(2), 288–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12185

Gupta, U., & Gupta, B. S. (2005). Psychophysiological responsivity to Indian instrumental music. Psychology of Music, 33(4), 363–372. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735605056144

Gustavson, D. E., Coleman, P. L., Iversen, J. R., Maes, H. H., Gordon, R. L., & Lense, M. D. (2021). Mental health and music engagement: Review, framework, and guidelines for future studies. Translational Psychiatry, 11(1), 370. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01483-8

Honing, H., & Ladinig, O. (2009). Exposure influences expressive timing judgments in music. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 35(1), 281. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012732

Inguscio, B. M. S., Cartocci, G., Sciaraffa, N., Nicastri, M., Giallini, I., Aricò, P., & Mancini, P. (2024). Two are better than one: Differences in cortical EEG patterns during auditory and visual verbal working memory processing between unilateral and bilateral cochlear implanted children. Hearing Research, 446, 109007. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heares.2024.109007

Jacobsen, S., Meiron, O., Salomon, D. Y., Kraizler, N., Factor, H., Jaul, E., & Tsur, E. E. (2020). Integrated development environment for EEG-driven cognitive-neuropsychological research. IEEE Journal of Translational Engineering in Health and Medicine, 8, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1109/JTEHM.2020.2989768

Jansma, J. M., Ramsey, N. F., Coppola, R., & Kahn, R. S. (2000). Specific versus nonspecific brain activity in a parametric N-back task. Neuroimage, 12(6), 688–697. https://doi.org/10.1006/nimg.2000.0645

Justeau, S., Musson, A., & Rousselière, D. (2021). Locked down. A study of the mental health of French Management School students during the COVID-19 health crisis using the POMS questionnaire. https://doi.org/10.22004/ag.econ.313664

Kang, A. (2023). Creative Problem-Solving and music: Analyzing the correlation between music and divergent thinking abilities. Journal of Behavioral and Brain Science, 13(11), 199–205. https://doi.org/10.4236/jbbs.2023.1311013

Kasuya-Ueba, Y., Zhao, S., & Toichi, M. (2020). The effect of music intervention on attention in children: Experimental evidence. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 14, 511950. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.00757

Kawasaki, M., Kitajo, K., & Yamaguchi, Y. (2010). Dynamic links between theta executive functions and alpha storage buffers in auditory and visual working memory. European Journal of Neuroscience, 31(9), 1683–1689. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07217.x

Koshino, H., Minamoto, T., Yaoi, K., Osaka, M., & Osaka, N. (2014). Coactivation of the default mode network regions and working memory network regions during task Preparation. Scientific Reports, 4(1), 5954. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep05954

Kučikienė, D., & Praninskienė, R. (2018). The impact of music on the bioelectrical oscillations of the brain. Acta Medica Lituanica, 25(2), 101. https://doi.org/10.6001/actamedica.v25i2.3763

Kume, S., Nishimura, Y., Mizuno, K., Sakimoto, N., Hori, H., Tamura, Y., & Kataoka, Y. (2017). Music improves subjective feelings leading to cardiac autonomic nervous modulation: A pilot study. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 11, 108. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2017.00108

Lamichhane, B., Westbrook, A., Cole, M. W., & Braver, T. S. (2020). Exploring brain-behavior relationships in the N-back task. Neuroimage, 212, 116683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.116683

Landis-Shack, N., Heinz, A. J., & Bonn-Miller, M. O. (2017). Music therapy for posttraumatic stress in adults: A theoretical review. Psychomusicology: Music Mind and Brain, 27(4), 334. https://doi.org/10.1037/pmu0000192

Leubner, D., & Hinterberger, T. (2017). Reviewing the effectiveness of music interventions in treating depression. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1109. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01109

Liang, W. K., Tseng, P., Yeh, J. R., Huang, N. E., & Juan, C. H. (2021). Frontoparietal beta amplitude modulation and its interareal cross-frequency coupling in visual working memory. Neuroscience, 460, 69–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2021.02.013

Limyati, Y., Wahyudianingsih, R., Maharani, R. D., & Christabella, M. T. (2019). Mozart’s sonata for two pianos K.448 in D-Major 2nd movement improves short-term memory and concentration. Journal of Medicine and Health, 2(4). https://doi.org/10.28932/jmh.v2i4.1127

Lundqvist, M., Herman, P., & Lansner, A. (2011). Theta and gamma power increases and alpha/beta power decreases with memory load in an attractor network model. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 23(10), 3008–3020. https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_00029

Maghsoudipour, M., Jamshidzad, M., A Zakerian, S., Bakhshi, E., Amoozadeh, E., & Moshtaghi, S. (2017). Assessing the effect of three types of music on working memory performance of medical sciences students of Tehran. Occupational Medicine, 9(2), 83–92. https://sid.ir/paper/207018/en SID.

Mammarella, N., Fairfield, B., & Cornoldi, C. (2007). Does music enhance cognitive performance in healthy older adults? The Vivaldi effect. Aging Clinical and Experimental Research, 19(5), 394–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03324720

Manca, M. L., Bonanni, E., Michelangelo, M., Vladimir, G., & Siciliano, G. (2020). Mozart’s music between predictability and surprise: Results of an experimental research based on electroencephalography, entropy and Hurst exponent. Activitas Nervosa Superior Rediviva, 62(3–4), 106–114.

Manza, P., Hau, C. L. V., & Leung, H. C. (2014). Alpha power gates relevant information during working memory updating. Journal of Neuroscience, 34(17), 5998–6002. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4641-13.2014

McNair, D. M., Lorr, M., & Droppleman F. M. (1971). Profile of mood states, San Diego, CAL. Educational and Industrial Testing Service, 1971.

Meiron, O., & Lavidor, M. (2013). Unilateral prefrontal direct current stimulation effects are modulated by working memory load and gender. Brain Stimulation, 6(3), 440–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2012.05.014

Meiron, O., Ezra Tsur, E., Factor, H., Jacobsen, S., Salomon, D. Y., Kraizler, N., & Jaul, E. (2021). Left-prefrontal alpha-dynamics predict executive working-memory functioning in elderly people. Cognitive Neuroscience, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/17588928.2021.1911977

Meiron, O., David, J., & Yaniv, A. (2022). Early auditory processing predicts efficient working memory functioning in schizophrenia. Brain Sciences, 12, 212. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci12020212

Menon, V., & Levitin, D. J. (2005). The rewards of music listening: Response and physiological connectivity of the mesolimbic system. Neuroimage, 28(1), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.05.053

Mercado, F., Ferrera, D., Fernandes-Magalhaes, R., Peláez, I., & Barjola, P. (2022). Altered subprocesses of working memory in patients with fibromyalgia: An event-related potential study using N-back task. Pain Medicine, 23(3), 475–487. https://doi.org/10.1093/pm/pnab190

Müller-Putz, G. R. (2020). Electroencephalography. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 168, 249–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63934-9.00018-4

Netz, Y., Zeav, A., Arnon, M., & Daniel, S. (2005). Translating a Single-Word items scale with multiple Subcomponents–A Hebrew translation of the profile of mood. Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, 42(4), 263–270.

Nikolin, S., Tan, Y. Y., Schwaab, A., Moffa, A., Loo, C. K., & Martin, D. (2021). An investigation of working memory deficits in depression using the n-back task: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 284, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.084

Onton, J., Delorme, A., & Makeig, S. (2005). Frontal midline EEG dynamics during working memory. Neuroimage, 27(2), 341–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.04.014

Owen, A. M., McMillan, K. M., Laird, A. R., & Bullmore, E. (2005). N-back working memory paradigm: A meta‐analysis of normative functional neuroimaging studies. Human Brain Mapping, 25(1), 46–59. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20131

Pavlov, Y. G., & Kotchoubey, B. (2020). The electrophysiological underpinnings of variation in verbal working memory capacity. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 16090. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-72940-5

Permatasari, A. S. (2021). The Effect Of Mozart’s Music Therapy On Maternal Anxiety During The First Stage Of The Active Phase. Jurnal Profesi Bidan Indonesia, 1(02), 34–42. Retrieved from https://pbijournal.org/index.php/pbi/article/view/9

Rauscher, F. H., Shaw, G. L., Ky, K. N., & Wright, E. L. (1994). Music and spatial task performance: A causal relationship. The American Psychological Association 102nd Annual Convention.

Rauscher, F. H., Shaw, G. L., & Ky, K. N. (1993). Music and Spatial task performance. Nature, 365, 611. https://doi.org/10.1038/365611a0

Rauscher, F., Robinson, D., & Jens, J. (1998). Improved maze learning through early music exposure in rats. Neurological Research, 20(5), 427–432. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616412.1998.11740543

Reybrouck, M., Vuust, P., & Brattico, E. (2018). Brain connectivity networks and the aesthetic experience of music. Brain Sciences, 8(6), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci8060107

Reybrouck, M., Vuust, P., & Brattico, E. (2021). Neural correlates of music listening: Does the music matter? Brain Sciences, 11(12), 1553. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11121553

Reynoso-Sánchez, L. F., Pérez-Verduzco, G., Celestino-Sánchez, M. Á., López-Walle, J. M., Zamarripa, J., Rangel-Colmenero, B. R., & Hernández-Cruz, G. (2021). Competitive recovery–stress and mood States in Mexican youth athletes. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 627828. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.627828

Rideout, B. E., & Laubach, C. M. (1996). EEG correlates of enhanced Spatial performance following exposure to music. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 82(2), 427–432. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1996.82.2.427

Sarnthein, J., VonStein, A., Rappelsberger, P., Petsche, H., Rauscher, F., & Shaw, G. (1997). Persistent patterns of brain activity: An EEG coherence study of the positive effect of music on spatial-temporal reasoning. Neurological Research, 19(2), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/01616412.1997.11740782

Sauseng, P., Klimesch, W., Doppelmayr, M., Pecherstorfer, T., Freunberger, R., & Hanslmayr, S. (2005a). EEG alpha synchronization and functional coupling during top-down processing in a working memory task. Human Brain Mapping, 26(2), 148–155. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20150

Sauseng, P., Klimesch, W., Schabus, M., & Doppelmayr, M. (2005b). Fronto-parietal EEG coherence in theta and upper alpha reflect central executive functions of working memory. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 57(2), 97–103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.03.018

Scharinger, C., Soutschek, A., Schubert, T., & Gerjets, P. (2017). Comparison of the working memory load in n-back and working memory span tasks by means of EEG frequency band power and P300 amplitude. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00006

Schellenberg, E. G., Nakata, T., Hunter, P. G., & Tamoto, S. (2007). Exposure to music and cognitive performance. Psychology of Music, 35(1), 5–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305735607068885

Sesso, G., & Sicca, F. (2020). Safe and sound: Meta-analyzing the mozart effect on epilepsy. Clinical Neurophysiology, 131(7), 1610–1620. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2020.03.039

Setiawan, A. S., Zidnia, H., & Sasmita, I. S. (2010). Mozart effect on dental anxiety in 6–12 year old children. Dental Journal (Majalah Kedokteran Gigi), 43(1), 17–20. https://doi.org/10.20473/j.djmkg.v43.i1.p17-20

Smith, A., Waters, B., & Jones, H. (2010). Effects of prior exposure to office noise and music on aspects of working memory. Noise and Health, 12(49), 235. https://doi.org/10.4103/1463-1741.70502

Taylor, J. M., & Rowe, B. J. (2012). The mozart effect and the mathematical connection. Journal of College Reading and Learning, 42(2), 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/10790195.2012.10850354

Tervaniemi, M., Makkonen, T., & Nie, P. (2021). Psychological and physiological signatures of music listening in different listening Environments—An exploratory study. Brain Sciences, 11(5), 593. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11050593

Trzesniak, C., Biscaro, A. C., Sardeli, A. V., Faria, I. S., Sartori, C. R., Vitorino, L. M., & Faria, R. S. (2024). The influence of classical music on learning and memory in rats: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Cognitive Processing, 25(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10339-023-01167-9

Tsoneva, T., Baldo, D., Lema, V., & Garcia-Molina, G. (2011). EEG-rhythm dynamics during a 2-back working memory task and performance. In 2011 annual international conference of the ieee engineering in medicine and biology society (pp. 3828–3831). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/IEMBS.2011.6090952

Tyng, C. M., Amin, H. U., Saad, M. N., & Malik, A. S. (2017). The influences of emotion on learning and memory. Frontiers in Psychology, 1454. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01454

van Esch, R. J., Shi, S., Bernas, A., Zinger, S., Aldenkamp, A. P., & Van den Hof, P. M. (2020). A bayesian method for inference of effective connectivity in brain networks for detecting the mozart effect. Computers in Biology and Medicine, 127, 104055. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compbiomed.2020.104055

Vatansever, D., Manktelow, A. E., Sahakian, B. J., Menon, D. K., & Stamatakis, A. E. (2017). Angular default mode network connectivity across working memory load. Human Brain Mapping, 38(1), 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.23341

Vigl, J., Ojell-Järventausta, M., Sipola, H., & Saarikallio, S. (2023). Melody for the Mind: Enhancing mood, motivation, concentration, and learning through music listening in the classroom. Music & Science, 6, 20592043231214085. https://doi.org/10.1177/20592043231214085

Vuust, P., Heggli, O. A., Friston, K. J., & Kringelbach, M. L. (2022). Music in the brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 23(5), 287–305. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41583-022-00578-5

Weinberger, N. (2004). M. Music and the brain. Scientific American, 291(5), 88–95. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican1104-88

Xing, Y., Chen, W., Wang, Y., Jing, W., Gao, S., Guo, D., & Yao, D. (2016a). Music exposure improves Spatial cognition by enhancing the BDNF level of dorsal hippocampal subregions in the developing rats. Brain Research Bulletin, 121, 131–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainresbull.2016.01.009

Xing, Y., Xia, Y., Kendrick, K., Liu, X., Wang, M., Wu, D., & Yao, D. (2016b). Mozart, mozart rhythm and retrograde mozart effects: Evidences from behaviours and neurobiology bases. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep18744

Xu, X., & Sun, J. (2022). Study on the influence of alpha wave music on working memory based on EEG. KSII Transactions on Internet and Information Systems (TIIS), 16(2), 467–479. https://doi.org/10.3837/tiis.2022.02.006

Yeun, E. J., & Shin-Park, K. K. (2006). Verification of the profile of mood states‐brief: Cross‐cultural analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(9), 1173–1180. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20269

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Prof. Nira Mashal, Prof. Gerry Leisman and Dr. Raed Mualem for their input in the initial development of the study.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Bar-Ilan University.

This research did not receive any funding.

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Informed consent

Informed consent was obtained from all participants involved in the study.

Institutional review board statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Bar-Ilan University (Ethics code is: 123, date of approval: 19 October 2023).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cohen, S., Tsur, E.E. & Meiron, O. Passively listening to Mozart’s sonata K. 448 enhances verbal working memory performance: a quantitative EEG study. Curr Psychol 44, 9342–9357 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-025-07755-6

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

Issue date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-025-07755-6