Abstract

Attention is described as a “scarce commodity” that is traded in “a marketplace.” This, it is further claimed, contributes to a “widespread sense of attentional crisis.” But is there really an attention market, and if so, what, if anything, is wrong with it? We defend the claim that there are markets in attention. We provide an account of such attention markets and use that account to address what is morally wrong with them. Our account draws on knowledge of how attention works and what roles it plays in the mind. The attention market trades in an ability to influence our attention – somewhat (though not exactly) like the labor market trades in an ability to influence how we use our capacity for work. Specifically, the commodity it trades in is attentional landscaping potential, viz. the ability to systematically influence patterns of attention by changes to the sensory environment individuals are exposed to. Attention markets thus, we argue, commodify influence over a human capacity that plays a central role in shaping individual experience, agency, and belief formation. This feature of attention markets makes them ethically problematic. As markets in access to external influence, attention markets pose a special threat to individual autonomy and escape the classical liberal defense of free markets. Those who value autonomy should worry about the attention markets that exist today.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

We seem to get a lot of free stuff. Free internet search. Free email. Free videos to learn French or cooking. Free movies, free entertainment and free news on cable TV. That’s nice. But: is it really free? Those who provide the free stuff are, after all, market actors. If they give us something, we must have something that they want from us in return. What is it?

A popular view: it is our attention.

It is claimed that attention is “a commodity, like wheat, pork bellies, or crude oil.” (Wu, 2017, p. 17). There is a “marketplace for attention” (Hwang, 2020, p. 12), it is said, that connects online platforms, advertisers, and us. This attention market is “the dark beating heart of the internet” (Hwang, 2020, p. 5), and attention is the world’s “most endangered” (Hayes, 2025) or “most valuable” (Becker, 2021) resource. “The true scarce commodity is increasingly human attention,”Footnote 1 said Microsoft CEO Satya Nadella already in 2014. The market in attention is supposedly defines our economy at large: “We’ve moved from an oil economy to an attention economy,” says podcaster and NYU professor Galloway (2022).

But is there literally a market that trades in attention as a commodity? One might worry that such claims are hyperbole or loose talk—the kind of thing CEO’s, podcast hosts, and journalists (and maybe law professors and economists) get away with, but not something consistent with the research on attention in psychology, neuroscience and philosophy. How can attention—a mental capacity—be traded in the same way as oil? Our first aim in this paper is to argue that there indeed exists an attention market. It is, however, quite different from a market in oil. It trades in an ability to influence our attention – somewhat (though not exactly) like the labor market trades in an ability to influence how we use our capacity for work.Footnote 2 We will provide an account of attention markets that connects work on such markets emerging in economics and lawFootnote 3 with the literature on the nature and role of attention in philosophy and psychology.Footnote 4 We argue that the scale and economic significance of the attention market can in part be explained by central features of attention as described in the philosophical literature, in particular the central role of attention in shaping agency and belief formation. The attention market is indeed one of the biggest markets today. And philosophy can help explain why.

Our second aim is to defend a claim about what is morally wrong with attention markets.

In the contemporary debate there is a “widespread sense of attentional crisis” (Wu, 2017, p. 6). From mental health to the end of democracy, there are few contemporary problems that have not been connected in some way to “the attention economy” and how it plays out on smart phones, social media and digital devices.Footnote 5 But many things may go wrong with our attention. And many things may be responsible for those wrongs. What, if anything, is morally wrong specifically with trading attention in the marketplace? Nothing as such, one might argue. One might here appeal to a general liberal defense of the market.Footnote 6 An autonomous agent should be free to trade with another autonomous agent. To put it bluntly: if you want free email or access to a powerful search engine more than full control over your attention, the state should not interfere and deny you that wish.

We argue that the liberal defense of the attention market fails. Attention markets are markets in access to influence. The commodity it trades in is one of the primary means by which others can change us. As such the attention market poses a threat to self-determination and autonomy. Appeal to autonomy thus cannot be used in its defense. Even people who are generally in favor of free markets often think that markets in certain goods or capacities require special treatment: drug markets, prostitution or surrogacy are some important examples. We argue that the attention market is a market that requires such special ethical treatment. Our approach connects the study of ethical concerns about commodification and markets in such ‘contested commodities’Footnote 7 with the emerging area studying ethical (and other normative) questions about attention at both the individual and collective level.Footnote 8 The attention market raises important ethical concerns about external influence on our attention. Respect for autonomy does not yield a free attention market but one with clear ethical bounds.

Our paper is structured as follows. First, we defend the idea that there are literally attention markets, and we provide a philosophical account of how they work (Sects. 1–3). We argue that there are markets in attention in the sense that there are markets in what we call attentional landscaping potential, i.e. the ability to systematically influence patterns of attention by changes to the sensory environment individuals are exposed to.Footnote 9 Understood in this way, the idea of an attention market can be understood literally: the commodity they trade in is that potential.

We then turn to the ethical implications of the attention market as we have articulated it. We first consider some reasons why markets in attentional landscaping potential should not be considered especially problematic (Sect. 5). We then show that these initial reasons are misleading. In Sect. 6, we argue that markets in attention, because they are markets in access to external influence over a special and core element of people’s mind, pose an intrinsic threat to individual autonomy. As a result, the scale of contemporary attention markets makes living an autonomous and non-alienated life difficult for billions of people.

2 The basic structure of attention markets

We begin with some familiar examples. Consider the following:

Video Streaming. Individuals go online to watch videos they enjoy or want to learn from. They don’t pay any money to those producing the videos or to the platform hosting them. They sign an agreement allowing the platform or the video producers to show them advertisement. Advertisers pay the video streaming platform and video producers for ad placement.

Social Media. Individuals go on social media platforms (to talk to their friends or to access the news, and more). They don’t pay any money to the social media platform. They sign an agreement allowing the platform to show them advertisement. Advertisers pay the social media platform for ad placement.

Search Engine. Individuals use a search engine to find information online. They don’t pay money to the company that provides those search capacities. Advertisers pay the search engine company for ranking certain search results highly or for placing advertisement in search results or in other parts of the screen.

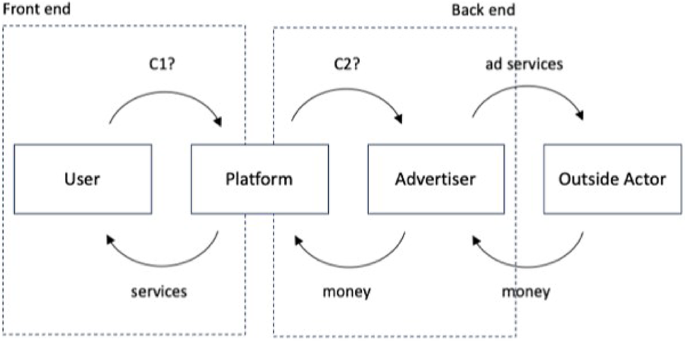

We will argue that these examples involve attention markets. More precisely, attention is commodified in exchanges of attentional landscaping potential. To do this, we first need to understand the basic economic structure of these transactions (see Fig. 1) and to show that they can be understood as market transactions.

This basic structure involves the following features:Footnote 10

-

1.

There is a platform (or platform intermediary) that offers a service to users.

-

2.

This service is offered to users for free (without financial payment) or at lower than market costs.

-

3.

The platform earns a revenue from advertisers for the placement of advertisements who in turn get paid by outside actors.

-

4.

Advertisements are sold in dynamic auctions in real time.

-

5.

Advertisements and auctions are targeted to specific users by drawing on user data.

The basic structure of the interactions in the ‘attention market’. Arrows indicate an interaction (potentially a market transaction). They are labeled by which commodity is exchanged from one actor to another. C1 and C2 indicate two places where attention may be traded as a commodity. C1 is located in the front-end transaction, C2 in the back-end transaction

The basic structure of these interactions between users, the platform, and advertisers is two-sided. We can distinguish (from the user’s perspective) a front-end transaction (the transaction between users and platforms) and a back-end transaction (the transaction between the platform and the advertisers). All (or most) platform revenue is made on the advertiser side. In addition (not depicted), users interact with the outside actors that pay the advertisers (e.g. by buying certain products or by supporting certain political actors).Footnote 11

This front-end/back-end structure (features (1)-(3)) is shared by offline examples that do not involve dynamic auctions or the collection of user data (features (4) and (5)). Consider:

Television. Individuals watch entertainment, news, and other content on private broadcast television. They don’t pay any money to the broadcasting company. Advertisers pay the company to intersperse advertisement with the content.

For cases where services are offered at a lower than market cost (but not for free) consider:

Newspaper. Individuals read a newspaper. They pay the newspaper a comparatively low price. The newspaper makes much of its revenue from advertisers in exchange for placing advertisement in the newspaper.Footnote 12

Travel. Individuals go on a discounted vacation. They pay the travel agency a relatively small sum of money but agree to watch and listen to a sales pitch by an advertiser who pays the vacation company in exchange for providing them with a location and timeslot during the individual’s travels.Footnote 13

It has been estimated that, already in 2019, the average American spent about nine hours per day (more than they spend at work) in interactions with the structure just described – through a combination of being on social media, searching online, online shopping, watching television, reading newspapers, and more (Evans, 2019, 2020). The value of the market arguably described in this structure, estimated in terms of opportunity costs (Evans, 2020), is about 7 trillion USD, and, estimated by ad spending that goes to the three most important platform intermediaries (Alphabet, Meta, Amazon), is roughly 400 billion USD.Footnote 14 The basic structure thus describes the interactions between billionsFootnote 15 of users and some of the most powerful economic actors worldwide. Our analysis (like parts of the economics literature, see Evans, 2019, 2020) aims to capture all of these interactions, both offline and online, while also contributing to an understanding of why the online variant has been especially successful.

Several aspects of the basic structure are striking. First, at the front end, no money changes hands. Users seem to get something for free (or at lower than market costs) from actors that don’t seem to be motivated altruistically to benefit them. Second, while platforms have been described as “attention brokers” (Wu, 2018) or “attention merchants” (Wu, 2017), the user-platform interactions differ from, say, brokers in the housing market in one crucial respect: the latter connect those who want housing (buyers) with those who offer it (sellers), yet the users don’t seem to use the platform primarily to connect with the advertisers on the other side of the platform: they want the platform’s services and only tolerate the advertisement.Footnote 16 Third, platforms compete for users, even though users don’t pay them, and even when those platforms offer very different services, e.g. streaming, search engines or social media.

In our view, the transactions represented by the basic structure are market transactions. At the frontend, users and platforms, acting on mutual disinterest, exchange one good for another. As we will argue, users exchange a commodity (C1 in Fig. 1)—attentional landscaping potential—in exchange for access to technological services. At the backend, platforms exchange a share of that commodity (C2 in Fig. 1) for payment from advertisers.

Typical market transactions involve the exchange of money. In the above cases, though, money only comes into the picture at the back end of the transaction. Thus, at the front end the ‘attention market’ would be what economist Evans (2019, p. 790) describes as “a massive barter economy.” To accommodate a broader range of transactions that also include those that do not involve the exchange of money, we propose the following understanding of a market:

A market transaction is (i) an interaction between some agents (‘marketeers’) where one economic good X gets exchanged for another economic good Y, (ii) where that interaction is voluntary by all marketeers; (iii) it is characterized by mutual disinterest (the marketeers don’t engage in the transaction to benefit the other and don’t expect the other to do so), and (iv) the exchange is regulated by a supply and demand or price mechanism.

An economic good here is understood as anything that (a) people may want, (b) that is scarce (not freely available), and (c) that can be exchanged with others. We will say that something is a commodity or commodified iff there exists an (economic) market for it (where it is exchanged). We reserve the terms ‘buying’ and ‘selling’ for monetized markets that involve the exchange of commodities for money.

While the concept of a market, and of commodification, is notoriously contested (see North, 1977), we take our characterization to be one that a wide range of friends and foes of markets can agree on (see footnote for more detail).Footnote 17

To illustrate, consider an example from the ethics of commodification literature: markets in sexual labor (sex work, or prostitution).Footnote 18 A paradigm for the commodification of sexual labor are practices where sex work is exchanged for money. But, in our analysis, ‘bartering’ practices where sexual favors are exchanged for, say, promotion at work would also involve the market-commodification of sexual capacities when and to the degree to which those exchanges approximate the features of market transactions we have sketched: it would have to be a voluntary but mutually disinterested interaction where there is something like a price that depends on the demand for, say, a certain kind of sexual interaction.

It is imporant to note that while market transactions are a distinctive form of human interaction, the distinction between them and other forms of interaction is blurry. An interaction may, for example, be to some degree voluntary and to some degree coerced; it may be unclear what goods or services are covered by the relevant agreement, the supply and demand mechanism might be imperfect; and more. Interactions may approximate the market paradigm more or less closely along the dimensions that define markets as above. We will say that an interaction is more or less marketized. This is especially easy to see outside of monetized markets. How marketized sexual favors are in a bartering context, for example, depends on voluntariness, disinterestedness, and the scale of the interactions.

Returning to the basic structure in Fig. 1, our claim is that it describes markets where attentional landscaping potential is exchanged as an economic good, in the sense now defined. Specifically, that potential is marketized to a relatively high degree in many actual interactions that follow the basic structure. In the next section we spell out more fully what attentional landscaping is and where it features in the basic structure.

3 Attention and attentional landscapes

Here then is what we mean:

Attentional Landscaping Potential. Agent A has attentional landscaping potential vis-à-vis agent B to the degree to which A can deliberately influence the probability that B will attend to some things and not others by changing B’s sensory environment. Footnote 19

Insofar as the ability to deliberately influence something is a form of control over it (see below), attentional landscaping potential is a certain form of control over the environment through which we can also have some form of indirect control over someone’s attention (including our own).

The value of attentional landscaping potential—both for those who give up control over it and to those who gain it—is tied to what attention is and what it does.

What, then, is attention and how does it work? Attention involves the selective directedness of an individual’s mind (Mole, 2021). It is the mental capacity that is realized when someone is paying or focusing attention on something, when their attention is captured or when they are doing something attentively. Paradigm examples of attention are perceptual: an individual pays attention to an object, feature, or person when they look at that object, feature, or person, or when they listen to something or someone. Attention also has cognitive manifestations concerning how much someone thinks about something or someone, or emotional variants manifesting in how much someone engages with something emotionally. One way to think about attention is as ‘prioritizing’ in the mind, perceptually, emotionally, or intellectually (Watzl, 2017).

Beyond this gloss, we highlight four features of attention.

Feature 1. Attention is central for agency. As Wu (2014, 2023) has emphasized, agents are faced with many inputs to the mind, and they could in principle engage in many different forms of behavior. Attention helps an agent solve the resulting ‘selection problem’ (Wu, 2023) by selecting objects or pieces of information to engage in a task that involves them. Psychological research describes more precisely how attention is involved in decision making, preference formation, choice, self-control and more (e.g. Gold & Shadlen, 2007; Krajbich et al., 2012; Dietrich & List, 2013; Berkman et al., 2017; Bordalo et al., 2022; Bhatnagar & Orquin, 2022). Somewhat more controversially, attention affects agency also by shaping subjective experience (Watzl, 2017) and our emotions (Todd et al., 2012; Mitchell, 2023).

Feature 2. Attention is central for learning and knowledge acquisition. An agent who pays no attention to something is unlikely to learn much about it (e.g. Simons & Chabris, 1999). Attention thus plays a central role for accessing information about something to update one’s beliefs, in inquiry, and in our epistemic perspectives (e.g. Smithies, 2011; Gottlieb et al., 2013; Camp, 2017; Siegel & Silins, 2019; Buehler, 2021; Saint-Croix, 2025; Munton, forthcoming; Yumuşak, 2024).

Feature 3. Attention is (to a non-trivial degree) under the agent’s direct voluntary control. An agent can, to some degree, voluntarily control what they pay attention to -for example, what to listen to, look at, or think about (see Watzl, 2017; Jennings, 2020). Indeed, we can often control our attention relatively directly. One way to think about what such voluntary control consists in is in terms of the degree to which the relevant aspects or instances of attention are influenced by the agent’s intentions (Wu, 2016).Footnote 20

Feature 4. Attention is also, to a non-trivial degree, influenced by agents’ sensory environment. While agents can control it, their direction of attention is also strongly influenced by which sensory stimuli they are exposed to. Attention is, among other things, influenced ‘bottom up’ by a range of low-level stimulus attributes (e.g. Wolfe & Horowitz, 2004), by what is surprising (e.g. Horstmann, 2015), emotionally charged (e.g. Todd et al., 2012; Todd & Manaligod, 2018), by what was previously rewarded (e.g. Anderson et al., 2011), and more.

While the details are a matter of philosophical and scientific debate, we take the above four features of attention as uncontroversial. They are also central to the role attention plays in the mind. Features 1 and 2 concern the downstream effects of attention vis-à-vis agency and belief formation while feature 3 and feature 4 concern how attention is in turn influenced by upstream causes both inside and outside the agent.

With those features of attention in view, let us return to our central concept: attentional landscaping potential.

The basic idea is this. The sensory environment agents are exposed to will affect what they attend to (see Feature 4). Standing in front of a blinking red light, for example, will drastically raise the probability that you will attend to that red light (though the probability won’t be one, since you could look away). Those who have some control over the sensory environment an agent is exposed to can thus deliberately change it in ways that make it more likely that individuals will attend to some things rather than others. Someone can, for example, hold up a red light in front of you so that you look at it. The same is true when they aim to get you to think about red lights by mentioning them in conversation (see Keiser, 2023). Those who have access to someone’s sensory environment (because they are in the same room, because they own the relevant space, or because they hold a certain position) thus hold a form of power – the power to influence the other’s attention. A friend can get you to think about something. The school might place a colorful poster at the front of the classroom that increases the probability that students will look at what is depicted. The political authorities might place a statue in the middle of the town square and increase the probability that the town’s citizens will look at it and think about, say, the greatness of the relevant historical figure.

We now make this more precise. We define the structure of the environment that affects the probabilities that a specific individual attends to certain things at some time (and how much they attend to them) as the attentional landscape that environment presents to this individual at that time. And we say that A engages in attentional landscaping vis-à-vis B when A deliberately changes the environment to affect the attentional landscape it presents to B. We will say that A has (a certain degree of) attentional landscaping potential vis-à-vis B (during a certain period of time) when (and to the degree to which) A can attentionally landscape B’s environment (during that period of time).

Importantly for our purposes, individuals can engage in attentional landscaping also vis-à-vis themselves. If you want to make it more likely that you pay attention to a red light (say, an alarm) you can make sure that this light occupies a central place in your environment. If you want to ensure that you pay enough attention to a certain person, you can put a picture of them in your wallet, and if you want to pay more attention to what is happening in economics you can exposee yourself to economics journals and lectures. In these cases, the individual controls their own patterns of attention indirectly by making changes to their sensory world.

The attentional landscape of a specific environment is agent-relative and path-dependent. One agent might find it hard to ignore the picture of a hamburger or cute cat, but another might not.Footnote 21 An agent who currently has some specific goal is more likely to attend to items related to that goal than an agent without that goal (e.g., agent A is more likely to look at red lights when searching for them). Further, the phenomenon that psychologists call ‘contingent capture’ shows that objects are more likely to automatically capture attention that match features (Folk et al., 1992) or are conceptually associated (Wyble et al., 2013) with an agent’s attentional control settings (e.g. another red thing or a greyscale picture of a strawberry). Previous reward and surprise (mentioned above) are other ways in which the attentional landscape of an environment depends on the specific agent and her previous history.

The degree of attentional landscaping potential an agent A has with respect to another agent B will depend on access to B’s sensory environment (if A is not in B’s physical proximity they may use of ownership over B’s environment or broadcasting abilities in the form of radio, TV, or digital devices), the capacity to change the sensory composition of that environment (e.g. by talking, through imagery, or moving images), the capacity to dynamically respond to B’s personal characteristics and current tasks (e.g. by knowing their personal history, and use that to, say, structure search rankings or run dynamic ads). A teacher has a relatively large attentional landscaping potential vis-à-vis her pupils (she can make them think about and look at things); by contrast, she has negligible attentional landscaping potential vis-à-vis people outside of her social circle. And someone who has the technological (and social) power to put up statues or display stimuli to someone on screens will, other things being equal, have more attentional landscaping than someone who lacks those powers. Most people have only negligible attentional landscaping potential vis-à-vis most others (aside from their close friends and family).

Let us now see how attentional landscaping is involved in our opening examples and those that share the basic structure. At both the front end and back end, a user’s attention will be affected in various ways. At the front end, a user enters a sensory environment that is partially controlled by the platform she engages with. Platforms (e.g., social media companies, newspapers, or even travel companies) design or organize environments in various ways (e.g., by placing content in specific areas of one’s feed or newspaper or setting up a conference room in a particular way). This affects user attention for as long as the user is engaged with that platform. A video playing at the top of a user’s screen, a political advertisement on the front page of a newspaper, or an engaging sales pitch in a conference room will make it more likely that an individual will direct her (perceptual) attention to the video, the news story, and the sales pitch than if those stimuli were absent, or appeared somewhere less prominent. In this way, platforms have access to attentional landscaping potential (and actively engage in attentional landscaping). Those have access to more technological capacities, more of an individual’s time, access to an individual’s current task or history (e.g. in form of personalized data about them) will have a larger attentional landscaping potential.

At the back end of the transaction, advertisers and other agents can influence user attention—and thus engage in attentional landscaping—through the content that they display. When a user watches a video, reads the newspaper ad, or listens to the sales pitch, she may learn something she otherwise would not have learned (see feature 2), think about ideas she otherwise would not have thought about, or engage with certain products she might otherwise not have engaged with (see feature 1). This, in turn, can affect how she acts (e.g., by buying certain products or voting for specific candidates).

Given the effects of attention on individual agency, attentional landscaping potential is clearly of value to economic actors. Attention, after all, affects preference formation, decision making, choice, self-control, belief formation, emotional and subjective experience, self-control and more (see Features 1 and 2 above). Based on the relevant psychological research, behavioral economists Bordalo et al. (2022) show that bottom-up salience (and attentional landscapes in our terminology) have a potentially large effect on economic decision making. Therefore, those who have attentional landscaping potential with respect to another can (to a comparably large degree) influence their economic choices. Since attentional landscaping potential is a rare opportunity (most people are outside the reach of someone’s attentional landscaping abilities), it is something that economic (or political) actors often will want. It can act as a resource for influence.

4 The attention market defined – or: how attention is commodified

We now have all the necessary elements to show that and how attention (or, more precisely: attentional landscaping potential) is commodified in examples like those we began with.

We have already seen that users agree (implicitly or explicitly, by signing contracts) to enter a sensory environment (where they receive the platforms services) whose attentional landscape the platform is able to influence. This gives the platform attentional landscaping potential. This potential is something advertisers are willing to pay the platform for. And this, we suggest, is precisely what they do: at the back end of the transaction, advertisers acquire access to some of the attentional landscaping potential of the platform in a monetized market exchange. They acquire the ability to, for example, use the conference room for a sales pitch, put advertisement in the newspaper, on TV, or on social media, are able to affect search engine rankings (or get information about what affects it), and more.

So understood, advertisers ‘get’ user attention at the back end of the transaction by getting access to a specific kind of influence on user attention: attentional landscaping potential. They can use that potential to influence their capacity for attention without legal ownership over that human capacity or a legal right to demand that this capacity be used in a specific way.

Is attentional landscaping potential the kind of thing that can be exchanged in market transactions? Market transactions, after all, involve economic goods. In what sense is attentional landscaping an economic good? Recall that an economic good is something that is scarce, desirable, and exchangeable. Attentional landscaping potential has these features. We have seen that not everyone is in a position to change a specific individual’s attentional patterns to a significant degree and, thus, attentional landscaping potential is scarce. It is also desirable, insofar as it affects what is salient to individuals, and this affects their economic choices. Finally, such a potential can be exchanged: someone can agree to expose themselves to another’s influence in exchange for something they want or need, and someone can rent out an environment they control for attentional landscaping.

Thus, we argue that while the attention market, the commodification of attention, or the ‘attention economy’ do not involve the literal sale of attention, they do literally involve the market exchange of attentional landscaping potential as a commodity. This potential is what is commodified in the attention market. Here then is the central claim.

The Commodification Claim. There exist practices of transactions that are marketized to a relatively high degree where access to attentional landscaping potential—viz. access to the ability to influence an individual’s attention by changing the sensory environment they are exposed to—is exchanged for other goods or services (non-monetized market commodification) or exchanged for money (monetized market commodification).

This is the precise sense in which there is an attention market. No aspect of it is figurative or loose talk; no more than talk of the ‘labor market.’Footnote 22 The attention market is a market in a form of influence on or control over attention. And our defense of the commodification claim does not require accepting a controversial conception of attention as a resource,Footnote 23 or the view that attention is owned by ourselves or can be owned by others. Indeed, the only claims about attention we need is that attention is influenced by an agent’s sensory environment, and that sometimes people can intentionally change which sensory environment another is exposed to.

We now say more to defend the commodification claim.

4.1 Relationship to advertisement

We take it as uncontroversial that the back-end transactions are paradigms of monetized market transactions. Something is bought and sold here. Yet why think that what is bought from the platform is ‘attentional landscaping potential’ rather than advertisement space? Indeed, this, roughly, is the terminology used in the relevant contracts. Meta makes 95% of its revenue in advertisement (see footnote 14). What does any of this have to do with attention?

Attentional landscaping comes into play, we argue, when and because the price mechanisms that govern the advertisement exchange markets track the attentional landscaping potential that comes with a specific ad space (including influence on, for example, search rankings).

Consider that advertisement varies in price depending on the ‘quality’ of the ad space: a whole page in the newspaper is more expensive than half a page. Some advertisement times on TV (e.g., during the Superbowl) are more expensive than others. The price mechanism for ads, at least under idealized circumstances, will track the demand there is for the ad space. The advertiser, of course, would like to influence the future behavior of the users (e.g. what they will buy, how much they are willing to pay, or their attitudes toward a product). But how much and in what way an advertisement will influence a user’s future behavior depends not only on the quality of the ad space (which the advertisers pay for) but also on the content of the advertisement. So, the price mechanism in the platform-advertiser exchange cannot directly track the influence on future behavior. For that reason, even though the outside actors at the end of the day may want to influence the user’s ‘behavioral futures’ (Zuboff, 2019, p. 8), the commodity exchange between the advertisers and the platform is not primarily a “behavioral futures market” (Zuboff, 2019, p. 8). Attentional landscaping potential, by contrast, is something the price mechanism can track: how many users will look at or listen to the advertisement, what their dwell-time on the advertisement will likely be, and how deeply they will engage with the ad in that space. These are exactly the types of measures that determine the price of e.g. online advertisement (see Wang et al., 2017).

Two more notes: first, while we claim that platforms sell access to attentional landscaping potential, this transaction is not perfectly marketized: advertisers and platforms exchange the rights to use a certain part of the world to create sensory stimuli. They do not exchange ownership over how exactly those stimuli will in fact affect users. Compare selling houses with a view of ocean. The price of the house will track the view, but whether the view remains need not be legally enforceable. Second, we are not claiming that the relevant pricing mechanism only tracks attention. Advertisements to the financially wealthy or politically powerful are likely worth more. Our claim is that a back-end transaction is an attention market to the degree to which its price mechanism does track attentional landscaping potential.

4.2 Commodified, stolen or enclosed?

Something may become a market commodity at some stage, even though it did not enter the marketplace through a market transaction. Someone might, for example, acquire an economic good by theft and then sell it in market transactions (e.g., organized bicycle theft).Footnote 24 Someone might also turn something that was not an economic good (since it was, for example, freely available to everyone) into such a good (e.g., the enclosure of the English commons).Footnote 25

Thus, that there is a market in attentional landscaping potential at the back end of the transaction does not entail that such potential is commodified at the front-end. The platform might not have acquired that potential from the users in a market transaction. Indeed, one might worry that it is impossible for users to exchange their attentional landscaping potential with the platform since they don’t own that landscaping potential and thus cannot give the rights to that potential to someone else.

It is true that the relevant exchange deviates from the paradigm market exchange in this way. Yet, we argue, attentional landscaping potential is marketized at the front-end where and to the degree to which the following is true: users knowingly accept the possibility that the platform will get into a position to affect the probabilities that they attend to various things (look at, listen to, think about certain things) in exchange for access to its services.

Consider our Travel example from earlier. During a 2-hour stretch of time, a traveler could expose themselves to many different stimuli: they could read a book, let a fellow traveler talk to them, or take in the sights in the old town. But our traveler instead signs a contract to sit in a conference room and expose themselves to a sales pitch given by whoever paid the travel agency for that opportunity. While our traveler did not own their attentional landscape, they did have attentional landscaping potential vis-a-vis themselves. They were able to control which sensory stimuli to expose themselves to – who or what, for example, to listen to. They gave up some of that potential by allowing another economic agent to have a certain type of influence over their attention. They did not allow that agent to control their attention fully: they only accepted the possibility that they would, for example, listen to the sales pitch if they are in a room where it is happening. The other examples share that feature: the user either explicitly signs a contract that they will expose themselves to advertisement or other paid influences (e.g. on social media, or search ranking) or can be said to operate under a reasonable expectation that they will be exposed to those influences (e.g. on commercial television, by reading newspapers, or using search engines).

On our view, attention is commodified at the front end where and to the extent to which users explicitly or implicitly agree to hand over some of the attentional landscaping potential they had vis-à-vis themselves to the platform and thus expose themselves to influences on their attention. Where such an agreement is absent, the relevant attentional landscaping potential is not acquired by the platform in a market transaction.Footnote 26 In cases where there is such an agreement, the interaction between user and platform (at least in an ideal market) is subject to supply and demand: users will stop using a platform when they deem the services offered unacceptable (e.g., when there are too many unwanted distractions or advertisement present). Where there are alternatives for users, they can evaluate how much an ad-free experience is worth to them. Such alternatives exist, for example, for travel, video streaming, social media, and more. Under ideal circumstances, the price users are willing to pay for such an alternative should measure how much they disvalue that advertisement. Given that the transaction is of a bartering type, we should expect that price mechanism to be relatively ineffective. Still, it is there.

5 Are attention markets benign?

We have argued that there are markets in attention, and that what is commodified in them is attentional landscaping potential. Those who have such potential possess a resource for influence. Attention has large and lasting effects on agency and belief formation (see Features 1 and 2 of attention, Section 3). Those who have a lot of attentional landscaping potential vis-à-vis some individual, therefore, can influence that individual to a relatively large degree. We now turn to the ethical implications of these markets. We will argue that attention markets, because of the commodity they trade in, threaten to undermine individual autonomy.

There is a rich literature (see footnote 7) on ‘the moral limits of the market’ (Sandel, 2012) or ‘contested commodities’ (Radin, 2001). Even those who favor a market economy often are skeptical of markets in sex work, commercial surrogacy, or human organs. The literature on contested commodities discusses the ethical grounds for imposing restrictions on such markets. Our analysis of the attention market lays the ground for a focused ethical analysis of it that draws on this literature. Should attention(al landscaping potential) be considered a contested commodity? We won’t be able to provide an analysis of all the relevant issues. We focus on a foundational ethical problem that arises from how the attention market affects individual users.Footnote 27

We begin with some examples. In some cases, the effects of the attention market on a user are clearly negative. Consider:

Travel. Oscar has been looking forward to his vacation. With his small pension, he doesn’t get to go often. Yes, he must spend some time siting in a conference room during a sales pitch, but it isn’t that long, and he can just think about something else, he thinks. But when the advertiser starts talking about mattresses, Oscar begins to listen. His is rather old, and his back has been hurting. They say it’s cheaper to buy the mattress as part of the sales promotion now rather than later. So, he does. Oscar later regrets his choice. His back is still hurting, and he now has to carefully budget to make it through the month.

Search. Sally searches “Is the measles vaccine safe?” by using a search engine (in which she types that phrase). The search engine ranks information (websites) and thereby alters her attentional landscape (see Munton, 2023).Footnote 28 That ranking would be epistemically optimal if it made most salient information that helped Sally with her inquiry (ibid.). Yet, the search engine acts as a platform in the attention market. As a consequence, the first search results are from paid content providers.Footnote 29 Their websites contain little relevant information regarding Sally’s inquiry. The attentional landscape she is facing makes it harder for her to achieve her (epistemic) aims.

Social Media. Mason logs onto a social media site to check in on her friends. At the top of her feed are videos that attract her attention – some are explicitly advertisements for products that she may want to purchase, others not. 45 min later Mason realizes that she has watched multiple funny cat videos but has yet to check in on any of her friends. Because Mason got distracted, she did not satisfy her desire for social interaction. Mason now feels more isolated and less happy.

Oscar, Sally and Mason were influenced in ways that don’t align with what they themselves would have wanted. And the explanation seems to be that they were exposed to a certain attentional landscape. They were neither coerced nor fully lost control over their own agency. Sally could have looked carefully to find the high-quality information she was looking for. Mason could have looked only at what her friends posted, and Oscar could have directed his mind to something else. What the platform’s attentional landscaping potential (and the advertisers’ share of it) did instead was change the probability that our agents attended in some way or other. To mix metaphors: because they were in the attention market, they were swimming against a stream that made it more likely that they ended up in one place rather than in another. In the cases we have described this place wasn’t where they, on reflection, would have wanted to be.

These examples show that the attention market clearly can have negative consequences. Given how much that market intersects with other areas of life, externalities are almost inevitable. The attentional landscapes we are exposed to, after all, affect what we can and will learn, our emotions, decisions and more. But attention markets can also have positive consequences: those without financial resources, for example, as we noted at the start of the paper, get access to a lot of stuff: from internet search to email, social networking capacities, cheaper products and vacations. Whether the net effects of attention markets on social welfare in total are positive or negative is hard to assess. The data, for example, on even a small slice of what would be relevant to that calculation—how social media affect teenage mental health—is very large and complex, indeed.Footnote 30

Yet, independent of the precise net social welfare effects, one might suggest that attention markets as such, cannot be ethically especially problematic.

First, one might, correctly in our view, point to the ubiquity of attentional landscaping in human life. Oscar’s enjoyment of his vacation may also have been interrupted by an annoying fellow traveler; Sally’s child may demand that she pay attention to them right now!; a statue in front of Mason’s town hall shapes what she looks at on her way to work and what she emotionally foregrounds (see Archer, 2024); schooling directs students’ attention to some topics and not others. Attentional landscaping is everywhere. We affect each other’s attention, and we don’t always get what we want as a result. In light of this, we might ask: why worry specifically about markets in attentional landscaping potential?

Second, a friend of the market might suggest that markets, in general, are a good thing: market transactions involve or, as Buchanan (1964) puts it, “embody” voluntary agreement. Sally, Mason and Oscar didn’t reach their aims in the examples above, but their choices seem to reveal that they presumably thought themselves better off with search capacities, social networking, and access to cheap vacations than without them. As Chen (2024) argues, the attention market, like other markets, will – under ideal conditions – reach an equilibrium that maximizes the average expected utility for all participants. The best we can do is to ensure that the attention market is indeed unimpeded and well-functioning. From this perspective, one should be suspicious of any attempt to trace concerns about Big Tech or the vaguely specific ‘attention economy’ (see Castro & Pham, 2020) to the marketization of attention. Instead, one might trace them to monopolization (Prat & Valletti, 2022; Wu, 2018) or to the emergence of a new form of ‘technofeudalism’ (Varoufakis, 2023) that aligns political and technological powers in ways that is exactly not a market-sphere.

Third, one might point out that the impact on individuals in the attention market is a lot less dramatic than, say, the impact of the labor market, let alone the impact of commercial surrogacy or sex work. In the labor market, pre-existing inequalities can enable exploitation (e.g. Vrousalis, 2023; Wilkinson, 2003), and the hierarchical, anti-democratic, organization of companies lead to important ethical concerns (e.g. Anderson, 2017; Frega et al., 2019; Vrousalis, 2023). The power platforms and advertisers have over individuals seems to be much smaller, by comparison. Individuals, unlike in the labor market, do not hand full control over their capacities to someone else, they merely agree to let platforms and advertisers shape the environment in which they deploy their attention.

Finally, one might point to the problems with the opposite of free attention markets: state paternalism. Respect for personal autonomy requires that people can choose for themselves whether they most value free search engines or more control over the attentional landscapes they are exposed to. Autonomous individuals may make decisions they later come to regret but those decisions were still their own. To be autonomous also means to be able to make mistakes. It would be wrong for the state to interfere with that ability.Footnote 31

We contend that these initial reactions, while to be taken seriously, are misleading. Because the attention market is a market in the access to changing minds, that market – at scale – raises deep ethical worries about individual autonomy, alienation, and how we relate to our own preferences, beliefs and agency more generally.

6 Attention markets and autonomy

One of the chief defenses of unrestricted markets appeals to how markets both respect and increase personal freedom and autonomy (e.g. Mill, 1859/(Mill, 2002); Hayek, 1944; see also Taylor, 2022 for an overview). Markets are said to be “the institutional embodiment of … voluntary exchange processes” (Buchanan, 1964; see also Sugden, 2024). Those in favor of free markets often emphasize that markets increase individual options (e.g. Dworkin, 1988, 1993) or opportunities (Sugden, 2018). Markets – the liberal tradition emphasizes – are institutions that enable and help agents to carve out their own path in life and pursue their own goals and values (e.g., Dagan, 2017, 2018). Since autonomy is valuable, markets are, so the claim goes, a good thing.

But even if markets in general respect and increase freedom and autonomy, some specific markets may threaten to undermine them.Footnote 32 This, we argue, is the case for attention markets.

Attention markets are markets in the capacity to steer people by a subtle and yet powerful force (attentional landscaping). That such markets pose a threat to autonomy, we think, will follow from a wide range of philosophical opinions on the nature of autonomy.Footnote 33 For our argument here, and with the liberal tradition, we will understand autonomy as an individual’s ability to live a life that is genuinely their own.Footnote 34 We will follow a prominent view in the contemporary literature that autonomy requires non-alienation (Christman, 1991, 2009; Enoch, 2016, 2017, 2020, 2022): to be autonomous an individual must be able to live according to her own deep values and commitments. Autonomy requires “coherence” (Ekstrom, 1993) or “harmony” (Enoch 2020) between one’s deep commitments and how one’s life actually unfolds. A classic articulation of this basic idea relies on conformity between an agent’s first-order and her higher desires (Frankfurt, 1988; Dworkin, 1988). On this articulation, users would be non-autonomous if the preferences they manifest in the attention market are not ones they reflectively endorse (see Williams, 2018, p. xii and p.7). Yet, arguably someone’s higher order desires might fall in line with their first order desires, and they could still live an alienated life: they may have wanted to resist the processes that led to their desires in the first place (Christman, 1991, 2009). We will thus understand autonomy as requiring that an individual is able to live according to her own values and commitments and that those values and commitments are her own in the sense that she is able to also endorse the processes that influence their formation (Christman, 2009; Enoch, 2022).

With this notion of autonomy in view, consider the attention market again. Markets in attention are markets in influence. They expose us to a stream of probabilistic and subtle influences that steer the path of life for us. An individual may be able to resist particular instances of influence on her agency. But she cannot resist the totality of influences on her. At scale, markets in attention undermine the capacity to live a self-determined life.Footnote 35

Attention markets threaten autonomy because of two key features: (1) what they trade in – attentional landscaping potential – and (2) their basic two-tier structure. The stochastic nature of how attentional landscapes affect us can hide that, at scale, the relevant processes of influence are powerful and person-transforming. And the two-tier structure of the attention market puts the individual always at one step removed from those influences. This makes it difficult—if not impossible—for her to know about and effectively respond to those influences.

When an individual user enters the attention market at the front end, they give the platform attentional landscaping potential and thereby agree to be influenced in some way. But how they will be influenced is not something the user has any control over, since that depends on how the platform and who it trades with at the back-end in fact uses that potential (i.e. how those actors change the sensory environment the user is exposed to). The user therefore takes a gamble: are the processes by which the new attentional landscape affects her preferences, beliefs, and decisions ones that she can endorse, and that accord with her own values and commitments? She can hope that they will be and that she, for example, through advertisement, learns about options she would have wanted to learn about, that those advertisements affect her desires and preferences in ways that reflect what she values.Footnote 36 But she has no control over whether they are. This is due to the very nature of the two-sided market she has entered.

An individual is thus at risk of exposure to attentional landscapes that influence her in autonomy-undermining ways. More specifically, those who acquire a significant amount of attentional landscaping potential can employ techniques of influence that, we submit, would not be ones agents would endorse. These include the following:

Manipulation. Those with large enough attentional landscaping potential can employ techniques such as deceptive “native advertising” (viz., advertisement that matches the appearance of the site on which it appears, e.g. unmarked effects on search ranking), “nagging” (viz. repeated appearance of banners or similar), “roach motel design” (viz. design that makes it easy enter a certain online environment but hard to quit, such as quitting a social media account), or various forms of social engineering (e.g. using parasocial pressures).Footnote 37

Value capture and tweaking. Actors can ‘tweak’ the desires, preferences, goals, or values of another in many individually subtle steps until they ‘fit’ the influencer’s goals or interests and, for example, get an agent to form a desire for and subsequently purchase their product. Attentional landscapers can use the agent-specific and path-dependent nature of attentional landscapes, and effects like contingent capture (see e.g. Folk et al., 1992; Wyble et al., 2013), the mere exposure effect and similar effects of attention on choice behavior (e.g. Bhatnagar & Orquin, 2022; Bordalo et al., 2022) to their advantage. They can be much more effective in this way when they operate with personalized data and powerful algorithms. Tweaking can also involve turning complex preferences (like maintaining friendships) into simplified preferences for countable goods (e.g. collecting likes on social media; see Nguyen, 2020).

Systematic obfuscation. Attentional landscaping potential can put someone in a position to create environments that systematically frustrate the aims of those who inhabit them. An agent might distract another with a salient stimulus, engage in deadcatting to divert attention,Footnote 38 or flood the zone with masses of hard to ignore issues, topics, and so on. The various forms of distractions here serve double purpose: they provide the other with something to attend to and they prevent them from reflecting on the processes that affect them (see Christman, 2009). In this way, an agent can prevent another from effectively pursuing their end and prevent them from noticing that they have not achieved it.

Manipulation, Value Capture and Tweaking, and Systematic Obfuscation are attention strategies that are available to those with enough attentional landscaping potential. They undermine the autonomy of anyone who is regularly exposed to them, since a life shaped by such influences is not a life shaped by a person’s own deep values and commitments (Enoch 2021). Without regulations that effectively limit the volume of influence and the way the relevant attentional landscaping potential is to be used, individual users must expect that both platforms and advertisers will use such strategies whenever it serves their (economic) interests.

At this point one might argue that it is not markets in attention as such that threaten individual autonomy, but just bad actors in those markets.Footnote 39 Consider Gibert (2023)’s recent account of what is morally wrong in wrongful manipulation. Manipulation is wrong, she argues, not because it interferes with a subject’s agency (she speaks of “practical reasoning”, p. 337) in a way that can be specified non-morally, but because it influences her agency in ways that interfere with her moral rights. If that’s correct, then online manipulation is wrongful only when and because a platform or back-end actor acts immorally. One might say something similar for the conditions under which tweaking and obfuscation undermine autonomy. But then the moral problem is not the market in attention, one might argue, but people acting immorally in that market. Bad actors exist in other markets too (and indeed they exist outside the market sphere). Why, then, think that the attention market as such undermines autonomy in morally relevant ways?

It is not clear that this really is an objection to our argument. The beauty of the invisible hand of the market is supposed to be that a free market will respect and increase autonomy even if there are bad actors. If, for example, a bakery manipulates me in morally objectionable ways, I can price that in and go to a different bakery instead. The problem with attention markets is that given their two-sided structure and the stochastic nature of the relevant influence users cannot effectively price in bad actors.

But, for the sake of argument, let us suppose that no one acts in ways that are as such immoral. The problem of autonomy-undermining influence nevertheless remains. This is due to the way that attentional landscaping works. Attentional-landscaping operates through changes in what Bordalo et al. (2022) call “bottom-up salience”. They show that the influence of bottom-up salience can explain a wide range of cases of “choice instability’” i.e., where people’s economically relevant behavior cannot be explained by appeal to a set of stable preferences. Consider, for example, the mere exposure effect first observed by Zajonc (1968). People tend to like things more just because they have seen them. The details of how this effect works, as Montoya et al. (2017) show, are highly complex (there are, for example, many interactions with other variables, and too much exposure can also decrease liking again). Just by being exposed to a range of stimuli in their interactions in the attention market, users thus will find themselves exposed to complex influences on what they like. Similar complexities pertain to the effects of visual attention on choice behavior: even if they don’t like them more, people tend to choose items they have looked at for longer or just before their decision making (Bhatnagar & Orquin, 2022). Bordalo and colleagues show that bottom-up salience effects can also explain selective recall from memory, contrast effects, underweighting or overweighing of attributes; it can explain intransitive preferences, framing and prominence effects, decoy effects, and more. In light of this, manipulation, tweaking, and obfuscation matter not primarily because they are as such morally wrong, but because they are instances of the subtle and yet powerful influence attentional landscaping has on individuals.

Autonomy requires that an agent be able to reflectively endorse the processes that have shaped her desires and other aspects of the path she has carved out in life. Yet, the subtle, probabilistic, and sub-personal influences of attentional landscapes on how individuals form preferences (and other mental states) is something that users do not and often cannot reflectively endorse. Systematically exposing individuals to this complex stream of psychological influences undermines people’s ability to understand and hence endorse the processes that shape key elements of their agency. For this we don’t need to assume that below the surface of the varying effective preferences, there exists, as Sugden (2018) puts it in his critique of parts of the Bordalo et al. research program, a “rational inner agent trapped inside and constrained by an outer psychological shell” (p. 82). Attention markets undermine autonomy not because they steer away from a supposed “true self” but because they are markets in steering agents as such. Attention markets disrupt the conditions for harmony to emerge between what is on the surface of our lives (i.e. attentional patterns) and what we each take ourselves to be.Footnote 40

In light of this, let us return to the arguments in defense of the attention market from the last section.

First, consider the point that attention markets are based on voluntary agreement. Individuals can simply choose not to take the gamble about the kind of influence they expose themselves to. If you want freedom from influence more than free email, you can just stay away from the platform. Reply: the problem is that any attention market is person-transforming: the user entering the market at time t, will while she is in that market be changed in ways that she cannot at t foresee. The very point of acquiring attentional landscaping potential is to affect user’s decision making by changing their patterns of attention: change what they learn about (and hence their beliefs), change their effective option set, change their preference, change what they select for action and more. Given the complex, subtle and stochastic nature of those influences, a user cannot be reasonably expected to have any estimate of how she might be affected in the process, not even a rough estimate of the relevant probabilities. A similar response can be made to another point. Sugden (2018), in his powerful defense of the market, argues that markets are to the mutual benefit of the participants, incentivizing transactions that are mutually advantageous. In the long run, the market forces will disincentivize any other behavior. The problem with attention markets is that that the two-tier structure and the stochastic nature of attentional influence prevents users from pricing in their autonomy loss at the front end. This, together with the fact that attention markets are of a bartering type, provides little hope that “the community of advantage” (Sugden, 2018) will, in this case, ever materialize.

Second, consider the point that problematic influences are not unique to attention markets. They are present in all attentionally landscaped environments, in and outside of markets in attention. Anyone who talks to a friend, buys a book, enters a school, or goes on a (full price and discounted) vacation will likewise be changed because of the sensory stimuli they will be exposed to. Reply: we agree that there are risks from attentional landscaping everywhere, in and outside of markets that trade in its potential. And these risks need to be mitigated. In cases of attentional landscaping in personal settings, attentional landscaping is often either easily escapable (you can leave the person who accosts you on the street or put down a book) or can be managed by relationships of mutual trust (in cases of spouses, friends or family). In the case of attentional landscaping by the state (e.g. by putting up statues, the use of nudging, or schooling), we would argue that the risks to autonomy are real and as significant as those by market actors. We should recognize the risks of indoctrination and the potentially large effects exposure to schooling has on children, for example. This is one reason why what students are exposed to at school, as well as the schooling process in many countries, is tightly controlled by public oversight. To prevent autonomy deficits through state-site attentional landscaping, democratic oversight is necessary. What is special about the market in attentional landscaping is that we should expect marketeers to act on the basis of their best economic interest, and not in the interest of those they stand to influence. Thus attention markets can lead to autonomy deficits even where there are no independent morally problematic social arrangements. We need democratic regulation of the attention market, like we need democratic oversight for schooling.

Third is the suggestion that, in comparison to, say, the labor market, where bosses have the power to order around individual workers, or, indeed, the coercive powers of the state, the way the attention market could influence individuals is rather small. Reply: it is certainly true that advertisement-run local newspapers should not be a prime area of moral concern. The same holds for relationship between a local carpenter and his apprentice or a smalltown mayor and the town citizens. What we have identified is a moral problem in the structure of attention markets as such. That problem becomes a major problem where that market is one that billions of individuals depend on for the majority of the waking life and when it has become one of the main engines of the economy at large. When individuals need to enter the attention market for essential services for a social life, for access to important information and news, for work tasks (e.g. email, search, and more), for entertainment, vacation, access to political information, access to forums for political deliberation, and more, the structural moral issues in the attention market become a moral issue that should be a center of moral concern and policy making.

Finally, consider the point that regulatory measures may be a remedy worse than the disease. State paternalism, after all, may also threaten personal autonomy. Reply: it is certainly true that state interference can undermine autonomy – especially by states that lack democratic legitimacy. Still, markets are an aspect of the Rawlsian basic structure. As such, their regulation is, we take, within the purview of the state.Footnote 41 Just as many social democracies have, for example, regulated the labor market in ways that mitigate some of the structural problems in unregulated labor markets, it is also legitimate for states to regulate the attention market in ways that mitigate its own distinctive structural problems. We add to this that the most severe autonomy undermining effects of the attention market are going to fall to the poor, and thus to those who are already disadvantaged. The poor, first, are more likely than others to make use of the attention market to access services or goods they could otherwise not afford. Second, policies that emphasize that users should be able to ‘price-in’ the long-term effects of attentional landscapes they are exposed to or the ability to exercise self-control in response to external influence, may rely on a model of individual decision-making that it is skewed toward those under at least moderate resource conditions (see Morton, 2017). Individuals living under scarcity, whose attention is mostly occupied by pressing current needs (Mani et al., 2013) are more likely to respond to those current needs rather than potential long-term costs. The platforms and advertisers they meet in the attention market can thus systematically take advantage of those tendencies for their own economic benefit. Any scheme of justice that emphasizes negative effects of social structures on those that are worse of would therefore support a stronger need for regulations in the large-scale attention markets we find today.

7 Conclusion

Let us conclude. We have provided an account of how the attention market works that is consistent with what is known about attention in philosophy and psychology. Attention markets are markets in what we have called ‘attentional landscaping potential’: the ability to change patterns of attention by changing the sensory environment individuals are exposed to. We have suggested that the ethical dimensions of these markets must be taken more seriously than they have been thus far and have set the groundwork for further work in this area. We have taken up one element of this analysis here, namely that such markets, at the scale they have taken, threaten to undermine autonomy and risk alienating persons from their own lives. We leave it to future work to determine how these risks should be managed. Starting points may be increased transparency about how attentional landscaping is used (e.g. transparency regarding algorithms used for search ranking), and measures to increase users’ collective bargaining power (e.g. requiring that agencies that act on users’ behalf are represented in the organization of any firm above some size that acts as a platform in the attention market). These would entail drastic changes to the contemporary media landscape.

Notes

We use the analogy between the attention market and the labor market here only for illustration purposes. Our account of the attention market does not substantially depend on accepting that analogy.

See e.g. Wu, 2014, 2023; Watzl, 2017; Jennings, 2020. See Mole (2021) and Wu (2014) for overviews. The literature in psychology is too vast to review here. Our approach draws on work by Chun et al. (2011), Krajbich et al. (2012) and Bhatnagar and Orquin (2022); as well as work in behavioral economics that relies on research in cognitive psychology (for an overview see: Bordalo et al., 2022). For a recent critique of a lack of engagement with the psychological literature on attention in discussions of the attention economy see White (2024). It should be clear in our discussion that our account does not rely on the sharp dichotomy between top-down and bottom-up attention that White, correctly, critiques as empirically unfounded.

E.g. Mill 1859/2002; Buchanan, 1964; Brennan & Jaworski, 2022; Sugden, 2018, 2024.

See e.g. Irving, 2019; Smith & Archer, 2020; Siegel, 2022; Gardiner, 2022; Watzl, 2022; Whiteley, 2023; Wu, 2024; Mole, 2024; Munton, 2022, 2023, forthcoming; Kaeslin, 2024; Saint-Croix, 2025; Kitsik, 2025; Browne and Kapelner (ms), Watzl (ms). Watzl (2022) for an argument for the normative significance of attention and various ways of evaluating it.

For more discussion of attentional landscaping, its social role and significance for a form of domination see Watzl (ms).

We follow economist Chen (2024). For some of the details of the online bidding market see e.g. Wang et al. (2017) and for a critique and popular overview of that bidding market see Hwang (2020). Our terminology follows the classic economics literature on two-sided markets (e.g. Rochet & Tirole, 2006; referenced also in Wu (2018).

Since for our purposes not much depends on the transaction between the advertisers and the outside actors that pay them, we will sometimes talk as if the platform directly interacts with the outside-actors who pay the advertising industry. It will be clear from context when we do so.

Wu (2017, 2018) traces the history of the attention market to the advertisement-based penny press in the US of the 1830s. This new media form (somewhat like today’s Tik-Tok or Instagram) was initially especially popular with the youth (see Thompson (2002) whose research Wu draws on) and was implicated in the emergence of political unrest, especially in the form of the Wide Awake movement (Grinspan, 2024).

Actors in this category include online shopping platforms like Amazon that make a revenue in part by paid advertisement or “sponsored” search ranking. Internal data released by Amazon to advertisers (https://advertising.amazon.com/) show, for example, that a product is 46 times more like to be clicked when advertised than when not.

The advertisement industry often describes itself in terms of brokerage. See e.g. Randall Rothenberg, former Executive Chair of Internet advertisement Bureau (IBA) in an interview here: https://www.facebook.com/business/inspiration/video/can-personalized-ads-and-privacy-coexist. If the ‘standard’ brokerage model provided a complete description of the user-platform interaction, then users should be willing to use then platform even there was only advertisement on it (and no services offered at all). Our discussion follows economists like Evans (2019) or Chen (2024) that this is not so.

See Herzog (2021) and Hussain (2023, Appendix). A few notes relevant for those with a stake in those debates: (i) the mutual disinterest characterization is compatible with the view that, as Bruni and Sugden (2008) point out, marketeers may have (or may necessarily have) a limited cooperative aim to do their part to make the transaction succeed and may, as Frye (2023) argues, be motivated by ulterior altruistic motives to, say, benefit their family, friends, certain political actors or society at large. (ii) we do not define commodities (as in Anderson, 1990a, p. 72) or commodification in terms of whether market norms are appropriate for the relevant good’s “production, exchange, and enjoyment”. This avoids critique leveled by Brennan and Jaworski (2022) and Frye (2023) against ‘anti-commodification’ views. We take the issue of what norms, if any, are essential to market transactions to be too complex to settle here. (iii) voluntary exchanges in a commodity do not necessitate a transfer of ownership over that commodity (consider sub-leases). We will allow implicit agreements where one party allows someone do something rather that giving them an enforceable right to do it. Insofar as the relevant agreement is implicit in that way, marketization is incomplete or deviates from the paradigm of a market transaction. (iv) one source for the notion of ‘commodification’, of course, is in Karl Marx’ influential treatment in Ch. 1 of Capital (especially Sect. 4 on commodity fetishism) and the rich history that follows him (and here especially György Lukács’ work on commodities and reification). Something becomes a commodity, for Marx, very roughly when its use value gets replaced by its exchange value. And the latter is measured by the socially necessary labor to produce it. For our purposes, we won’t assume any specific Marxist assumptions (such as the labor theory of value). A commodity in our sense (see main text) is anything that is exchanged in market transactions and as such there will be a price mechanism connected to an exchange value. We would value a deeper discussion that connects the attention market, as we define it here, with the Marxist body of work (Jhally & Livant, 1986; Bueno, 2016; Venkatesh, 2021). (v) We take market transactions (and hence market commodification) to be a distinctive type of human interaction. They exclude interactions that involve no economic goods, that involve no exchange (e.g. using tables, or attentional landscapes, without exchanging them for something else), that are not voluntary (e.g. rape or theft), that are based on genuinely altruistic motives regarding the other party (e.g. giving a genuine gift to someone), or that are too small-scale for a supply and demand or price mechanism to find application (e.g. A cooks in exchange for B doing the dishes). See Polanyi (1944). Note that we do not follow Polanyi’s terminology in treating human labor, land or money as merely ‘fictitious commodities.’ We take this to be mostly a terminological issue. Even if these are, in our terminology, real commodities, Polanyi’s substantial analysis may be correct that they play a structuring role in human interactions that no mere commodity could play, and he might be correct in his argument that traces wide-scale societal problems in the 19th and 20th century to the markets in labor, land and money. Indeed, we are open to the idea (though won’t argue for it here) that something similar holds for attentional landscaping.

One way to think about this is in terms of Munton’s (2022, 2023, forthcoming) notion of salience structures. On her view, an agent’s salience structure are the accessibility relations between possible objects of her attention. A salience structure tells us how likely an agent is to attend to some things and not others. On this picture, when someone attentionally landscapes an individual’s sensory environment, they change that individual’s salience structures.

For an alternative, see Buehler (2023). The details of what exactly voluntary control over attention amounts to won’t matter for our argument.

As another example, consider that drug-related items are hard to ignore for addicts because of their past experiences with them (Robinson & Berridge, 2008).

While we don’t argue for this here in detail, there are, arguably, deep and interesting connections between the labor market and the attention market. A market economy needs both production and consumption. The labor market marketizes the human capacities involved in production, while the attention market marketizes one of the main capacities influencing consumption.

This conception is prevalent in the public debate (Simon, 1971; Wu, 2018). See Navon (1984), Neumann (1987), Wu (2014), and Watzl (2017) for critiques of the resource conception of attention.

See also Fraser (2016) and Dawson (2016) who call this ‘expropriation’ and consider sex trafficking and chattel slavery as examples.