Introduction: Vegetal Motifs in Prehistoric Art

The topic of prehistoric mathematics seems at first glance to be beyond the borders of knowledgeability. Without written evidence it is difficult to assess the degree of the mathematical abilities possessed by prehistoric communities, how this knowledge was used and for what purposes. In this article we argue that the vegetal decoration of Halafian pottery vessels enables some understanding of these aspects.

The earliest artistic expressions of the European Upper Paleolithic era (c. 40,000–10,000 BC), which were both depicted on walls of caves and engraved on small portable objects, focused on anthropomorphic and zoomorphic figures. A few depictions were understood by Marshack as vegetal motifs (1991, figs. 65a, 66b, 67b, 94a, 105, 187), but Paul Pettitt (personal communication) debated this interpretation and argued that most of these depictions represent spears.

In the Near East only a few Upper Paleolithic artistic expressions have been found. They include two small plaques, one depicting a horse and the other part of an anthropomorphic figure and a schematic animal (Belfer-Cohen & Bar-Yosef, 1981, fig. 8; Belfer-Cohen & Bar-Yosef, 2009, p. 26). Later, around 14,000 BC in the Natufian culture of the Epi-Paleolithic era, there is an increase in the number of artistic expressions (Grosman et al., 2017; Rollefson, 2008; Yizraeli-Noy, 1999). In the Neolithic era (c. 9000–6000 BC), zoomorphic and anthropomorphic figures appear in large quantities and in almost every site (Garfinkel et al., 2010; Rollefson, 2008; Schmandt-Besserat, 2013; Yizraeli-Noy, 1999). However, to the best of our knowledge, vegetal motifs were introduced only around 6200 BC in the Halafian culture of north Mesopotamia, and were already depicted in a rather impressive manner.

The lack of vegetal motifs is rather surprising, since plants have always been extensively exploited by humans. Ethnographic observations on hunter-gatherer societies indicate that plants supply most of the human intake of calories. An association of plants with human symbolic behavior has been suggested for the Middle Paleolithic Neanderthal burials of Shanidar, but this suggestion has proved problematic (Sommer, 1999). A clear association of this kind, however, has been observed in burials of the Natufian culture at Raqefet Cave, Mt. Carmel, Israel, where plants and flowers were used to line graves (Nadel et al., 2013).

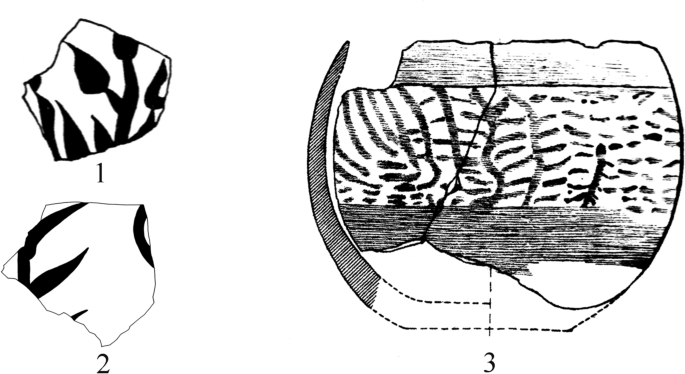

With the beginning of agriculture in the Near East in the Neolithic period, plant cultivation was essential to the economy, and yet plants were not depicted by these communities. The only possible symbolic connection suggested so far is the introduction of green beads, reflecting the desired color of cultivated fields (Bar-Yosef Mayer & Porat, 2008). The earliest depictions of vegetal motifs in the Near East are evident in the Halafian culture (Fig. 1), which flourished in northern Mesopotamia and the northern Levant from c. 6200 to 5500 BC (Akkermans, 2000; Gómez-Bach et al., 2016; Campbell, 2007; Watson, 1983a). The pottery of this culture, which is characterized by its high quality, elaborate shapes and outstandingly meticulous painting, is one of the peaks of ancient Near Eastern pottery in its aesthetics and craftsmanship (Davidson & McKerrell, 1976; İpek, 2019; LeBlanc & Watson, 1973; Nieuwenhuyse, 2007; Von Wickede, 1986). Previous studies of Halafian painted pottery have focused on aspects like the typology, production centers and geographical distribution of the motifs. Although scholars have sometimes noted vegetal motifs (Mallowan, 1936, fig. 27:14–16; Mallowan & Cruikshank Rose, 1935, figs. 77:7, 10, 17, & 78:11; Nieuwenhuyse, 2007, pp. 350–351, nos. 241, 249, 957, 263; Watson, 1983b, fig. 206:15–16, 26, 30), or motifs that we interpret as vegetal, none of these analyses has focused entirely on this phenomenon. Moreover, it was not recognized that this is the earliest appearance of vegetal motifs in Near Eastern symbolic expression.

The analysis of Halafian vegetal motifs presented here will attempt to answer four questions:

-

1.

What was chosen to be depicted? This aspect involves iconographic analysis of the vegetal motifs.

-

2.

How common are the vegetal motifs within Halafian painted pottery?

-

3.

Were these motifs distributed in restricted regions or over the entire Halafian territory? Did vegetal motifs spread into neighboring regions, such as eastern Mesopotamia or the southern Levant?

-

4.

Why were vegetal motifs introduced into human artistic expression in this particular era? Are there other developments in the Halafian culture that can be connected to the introduction of vegetal motifs?

Halafian Vegetal Motifs: Methodological Aspects

The data presented in our analysis derives from 29 Halafian sites and a regional survey in the Şirnak region. For some sites detailed book-length final excavation reports have been published, while others are represented only by short preliminary accounts. Together they present several tens of thousands of painted pottery sherds. The painted pottery bears various motifs, mainly geometric patterns but depictions of animals, human figures and plants as well. In each site only a small number of sherds were decorated with vegetal motifs, which have consequently received little attention in the research. It is only when the relevant data from the various reports is combined that the outstanding importance of the vegetal motifs becomes apparent.

Our methodology took into consideration the following aspects:

1. General issues with artistic expression. It should be emphasized that identifying artistic motifs involves a certain degree of interpretation. Indeed, many pottery sherds presented here as decorated with vegetal motifs were not recognized as such by the archaeologists who published them. The uncertainties inherent in visual perception and the analysis of artistic motifs are well-known issues that have been extensively discussed in research—both generally (Arnheim, 1974; Gell, 1998; Gombrich, 1982; Hasson et al., 2001; Kennedy, 1974; Palmer et al., 2013; Rubin, 1915; Todorović, 2020; Wade, 1982), and in the context of painted Halafian pottery (Garfinkel, 2003, pp.125–133; 2005; 2025). Thus, some of the items presented here may receive a different interpretation in the future. Nevertheless, we believe that once awareness is raised regarding the intensive use of vegetal motifs in Halafian pottery, these motifs will be better recognized in the art of the prehistoric Near East and beyond.

2. Sample strategy. All relevant reports on Halafian painted pottery available to us were included in the study, presented in alphabetical order in Table 1. We did not divide the Halafian sites into regions or chronological sub-phases, since the vegetal motifs are so rare that they currently cannot support reliable conclusions on these aspects.

3. Iconographic analysis of the vegetal motifs. The identification and iconographic analysis of the vegetal motifs are not always clear cut. In schematic styles, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish between a flower and a ‘star,’ or between a tree branch and a geometric design of parallel diagonal lines. In the same way, leaves are sometimes so schematically depicted that they have lost their natural characteristics. We first focus on vegetal motifs that can be identified without hesitation, and then suggest that similar, more abstract representations depict the same motif.

4. Iconographic analysis. Since the vegetal motifs are rare, and in many cases the pottery sherds as preserved contain only part of the entire depiction, we have classified the motifs into four basic categories: flowers, shrubs, branches and trees. This typology is based on the nature of the plant or the part of a plant that was chosen to be depicted. It is not always easy to distinguish branches from shrubs when only a segment of the depiction is preserved on the pottery sherd.

5. Statistical aspects. Only a few excavation reports present statistical data on the frequencies of the various decorated motifs unearthed at the site. How can a systematic and consistent picture be achieved for all the Halafian sites? The methodology that we chose was to count the number of sherds decorated with vegetal motifs out of the total number of decorated sherds published in each report. While this count indeed involved various biases, in the current stage of research this was the only way to achieve any kind of statistical picture.

For some sites the same decorated pottery sherd has been published twice, in a technical drawing and in a photograph. In such cases we were not always able to identify different presentations of the same sherd, and hence it is possible that in a very few instances the same sherd has been counted twice.

Another problem that we faced is the existence of both a preliminary report and an advanced or final report for the same site. In some cases the preliminary report presents vegetal motifs that were not included in the final report; such cases are Tepe Gawra (compare Speiser, 1927 with Tobler, 1950), Yarim Tepe II (compare Merpert & Munchaev, 1987 with Merpert & Munchaev, 1993a) and Umm Qseir (compare Hole & Johnson, 1986–87 with Hole, 2017). When the two reports present a very similar picture, Table 1 includes only data from the advanced publication. Nevertheless, interesting examples that are published only in preliminary reports have sometimes been included in the figures.

Vegetal motifs were employed in almost all Halafian sites. In the few cases where vegetal motifs are not reported, such as the sites of Tell Rifa‘at and Tell Zeidan, it is presumably because the entire assemblage was so small (20 and 14 sherds respectively). An indication that the vegetal motifs were fairly popular is the average frequency of 15.3% given at the end of Table 1.

Halafian Vegetal Motifs: The Data

The use of vegetal motifs in the decoration of Halafian pottery was observed by scholars when the first sites of this culture were excavated, although no detailed typological analysis of the motifs was carried out at the time. Even a recent detailed study of the decoration of Halafian pottery presents all the vegetal depictions under a single category (İpek, 2019). Moreover, no one seems to have noticed that this is one of the world’s earliest extensive uses of vegetal motifs, and the earliest in the Near East.

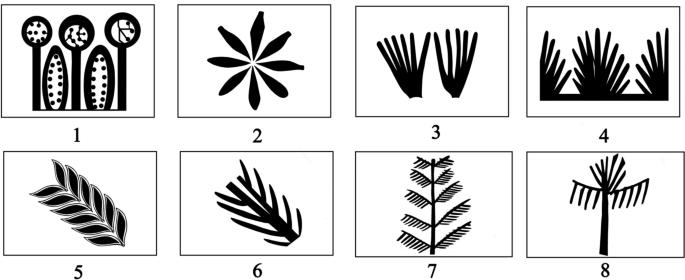

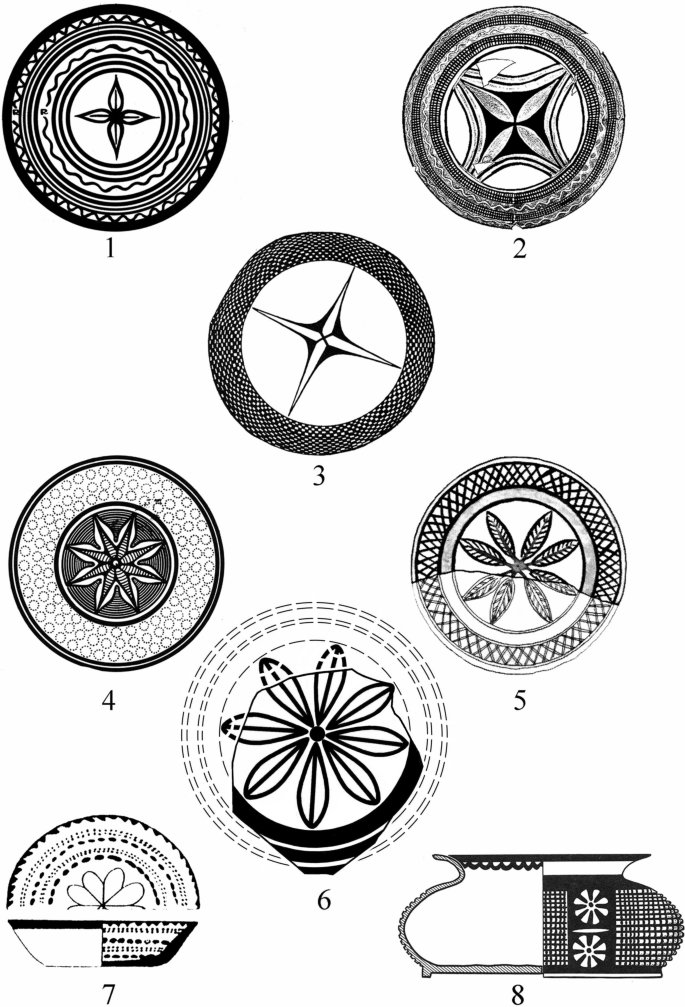

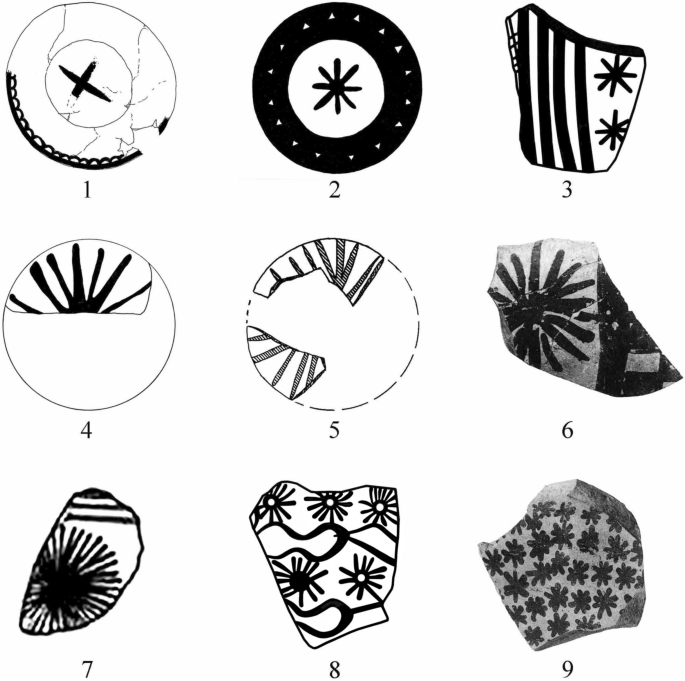

We classified the vegetal motifs into four basic categories: flowers, shrubs, branches and trees (Fig. 2). There are two additional groups, one consisting of decorated vessels with two different types of vegetal motifs and the other comprising vegetal motifs together with zoomorphic representations.

The classification of the vegetal motifs into four basic categories: 1–2 flowers, 3–4 shrubs, 5–6 branches, 7–8 trees

Flowers

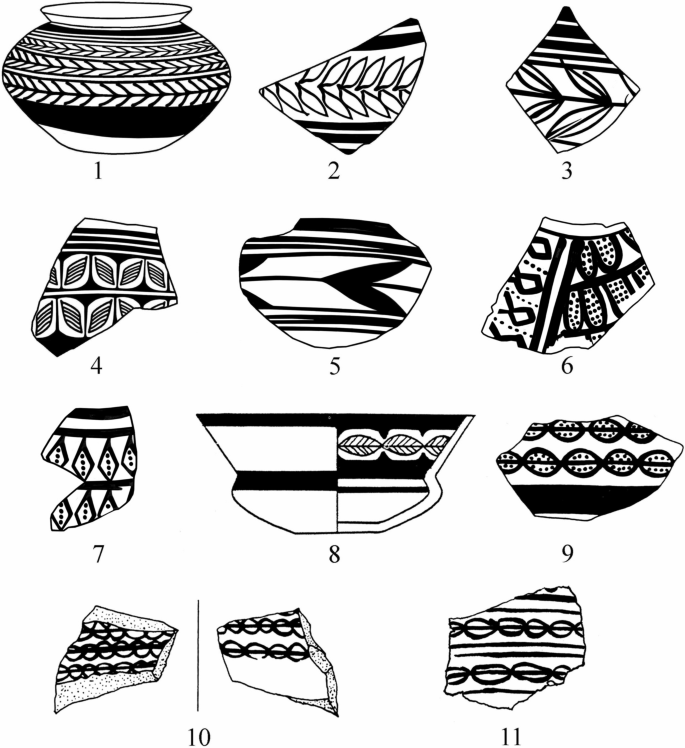

This is the most common vegetal motif in Halafian painted pottery, of which 375 examples have been identified. The depictions of flowers can be classified into seven sub-groups.

-

1.

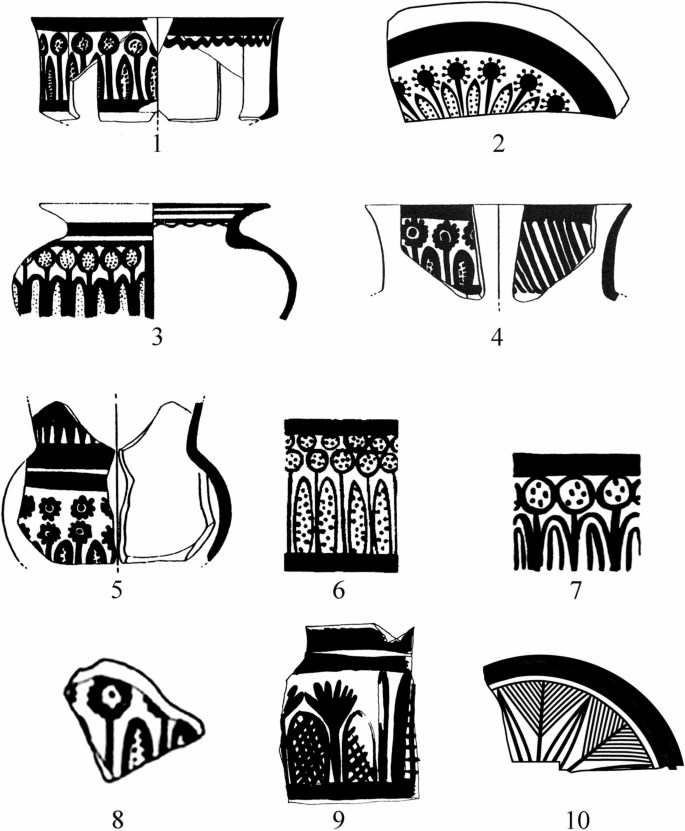

Seasonal short-leaved plants with two leaves, a tall stalk and a flower (Fig. 3). The leaves appear on both sides of the stalk, have an oval outline, and are covered with black dots. There are only two examples of leaves without dots (Fig. 3:9–10). The flowers are arranged on the vessel in a horizontal row, usually close to the base in bowls and on the base of the neck in jars. They are depicted schematically as a black circle, except for two unusual depictions in which the flower on top of the stalk is not rounded but more triangular in outline (Fig. 3:9–10).

-

2.

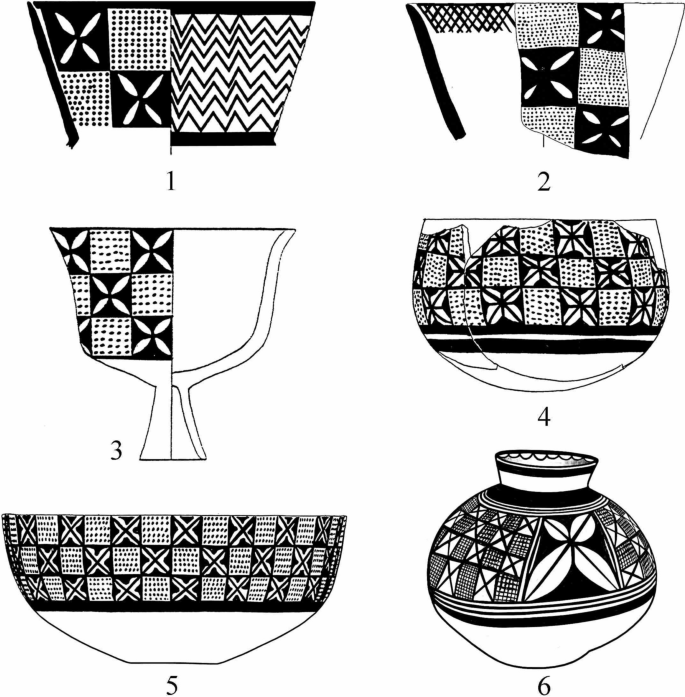

Small flowers with four petals inside the black squares of a checkerboard pattern (Fig. 4). In some cases each petal is divided into two by a black line (Fig. 4:4–6). The white squares are full of dots. This motif was arranged in horizontal bands on the vessels. In one case the pattern is different, with a single large flower (Fig. 4:6). Some scholars have emphasized the dots but did not recognize the motifs as flowers, describing the depictions as ‘horizontal dot-and-quatrefoil motif’ (Hole, 2017, fig. 17.3). This is the most common Halafian vegetal motif and is known from most sites; it generally appears more frequently than other plant motifs.

Seasonal short-leaved plants with two leaves, a tall stalk and a flower: 1. Yarim Tepe II (Merpert & Munchaev, 1987, fig. 15:9), 2. Yarim Tepe II (Merpert & Munchaev, 1987, fig. 8.25:6), 3. Arpachiyah (Hijara, 1997, pl. XXXV:243), 4. Yarim Tepe II (Merpert & Munchaev, 1987, fig. 15:1), 5. Yarim Tepe II (Merpert & Munchaev, 1987, fig. 15:4), 6. Arpachiyah (Mallowan & Cruikshank Rose, 1935, fig. 77:17), 7. Şirnak Valley (Erdalkιran, 2008, fig. 4:28), 8. Chagar Bazar (Mallowan, 1936, fig. 27:14), 9. Arpachiyah (Mallowan & Cruikshank Rose, 1935, fig. 20), 10. Chagar Bazar (Gómez-Bach et al., 2016, fig. 4)

Small flowers with four petals inside black squares of a checkerboard pattern: 1. Tell Halula (Cruells, 2013, fig. 14:1860), 2. Tell Amarna (Cruells, 2004, fig. 5.12:10,577), 3. Arpachiyah (Hijara, 1997, fig. 82:5), 4. Arpachiyah (Mallowan & Cruikshank Rose, 1935, fig. 66:6), 5. Arpachiyah (Mallowan & Cruikshank Rose, 1935, fig. 66:7), 6. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LXXV:2)

There are less-common variations of this motif, lacking the checkerboard pattern. Sometimes the flowers are arranged in a horizontal row, sometimes a flower touches a flower, and sometimes two flowers are arranged vertically (Fig. 5:1–5). There is also the arabesque style, in which the same petal is common to two different flowers (Fig. 5:6–10).

Small flowers with four petals in various compositions: 1. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. XCIII:6), 2. Chagar Bazar (Mallowan, 1936, pl. II:6), 3. Ugarit (De Contenson, 1992, fig. 191:1), 4. Ugarit (De Contenson, 1992, fig. 212:8), 5. Chagar Bazar (Mallowan, 1936, pl. II:8), 6. Arpachiyah (Mallowan & Cruikshank Rose, 1935, fig. 60:3), 7. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LI:7), 8. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LI:8), 9. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LI:10), 10. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LI:4)

-

3.

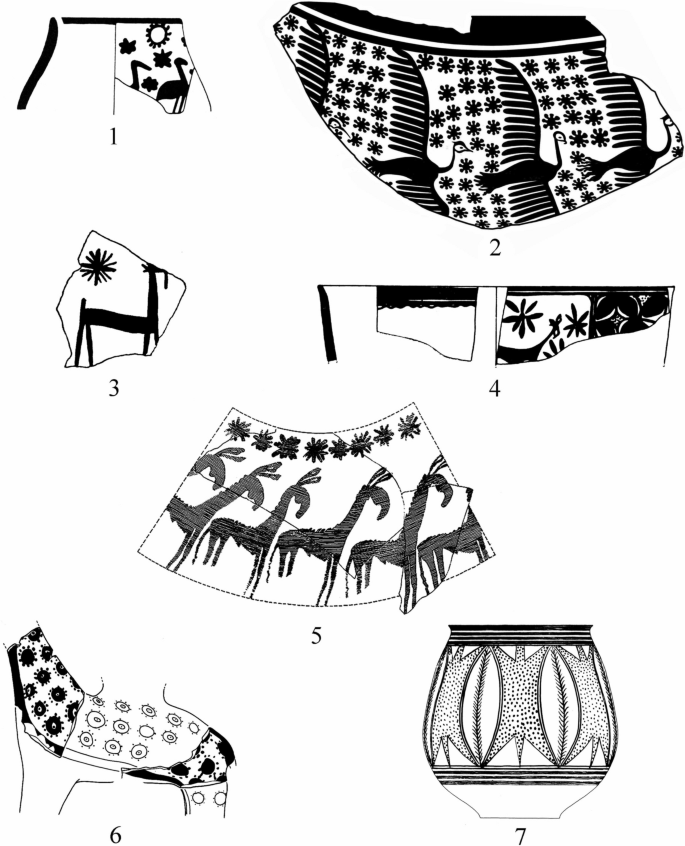

A meticulously executed drawing of a single large flower, depicted in a symmetrical arrangement that is typical of plants of the Compositae (Asteraceae) family. This family, one of the largest in the botanical world, is characterized by round, symmetrical flowers. Each flower usually consists of two parts: a dense inflorescence in the center and protruding petals around the entire circumference. Many of the flowers in this family, such as daisies, chrysanthemums and sunflowers, are striking in their color. The depictions on the pottery vessels, however, are too schematic to enable the identification of specific plants.

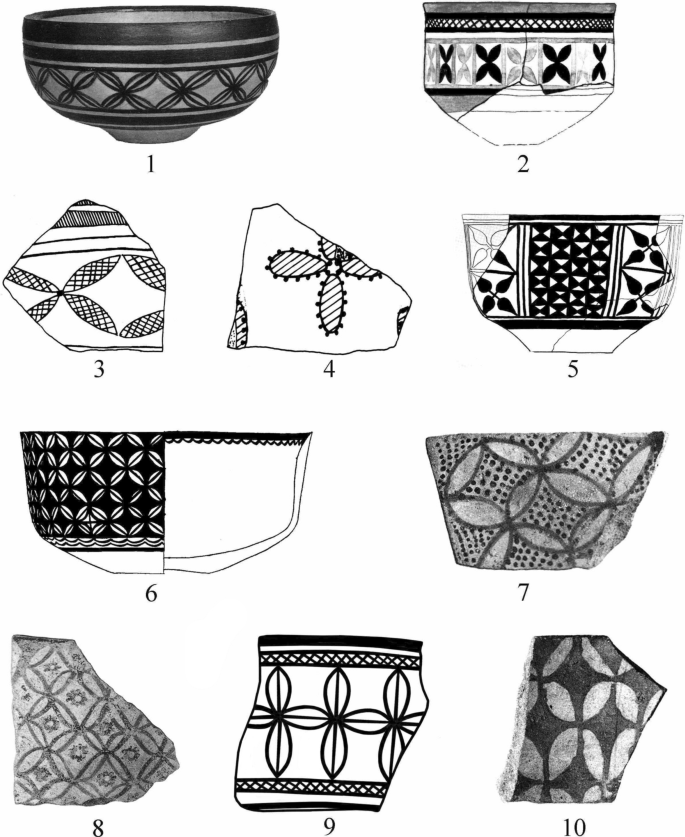

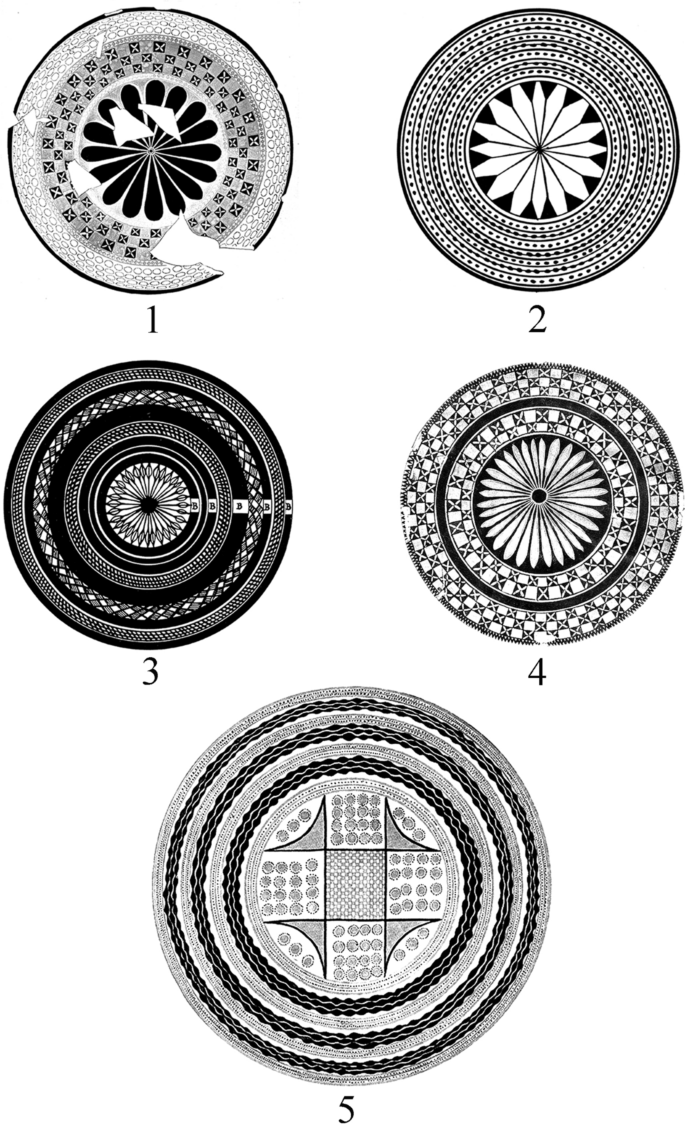

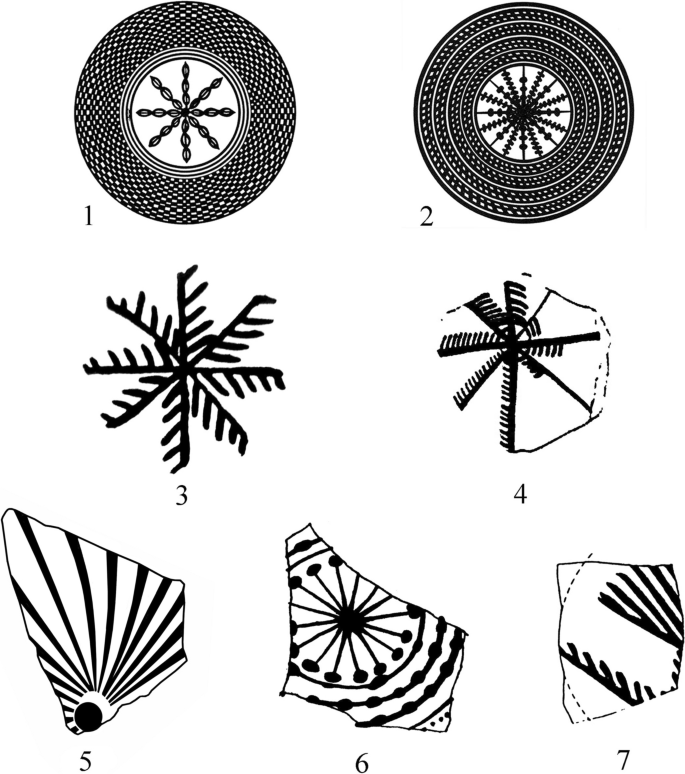

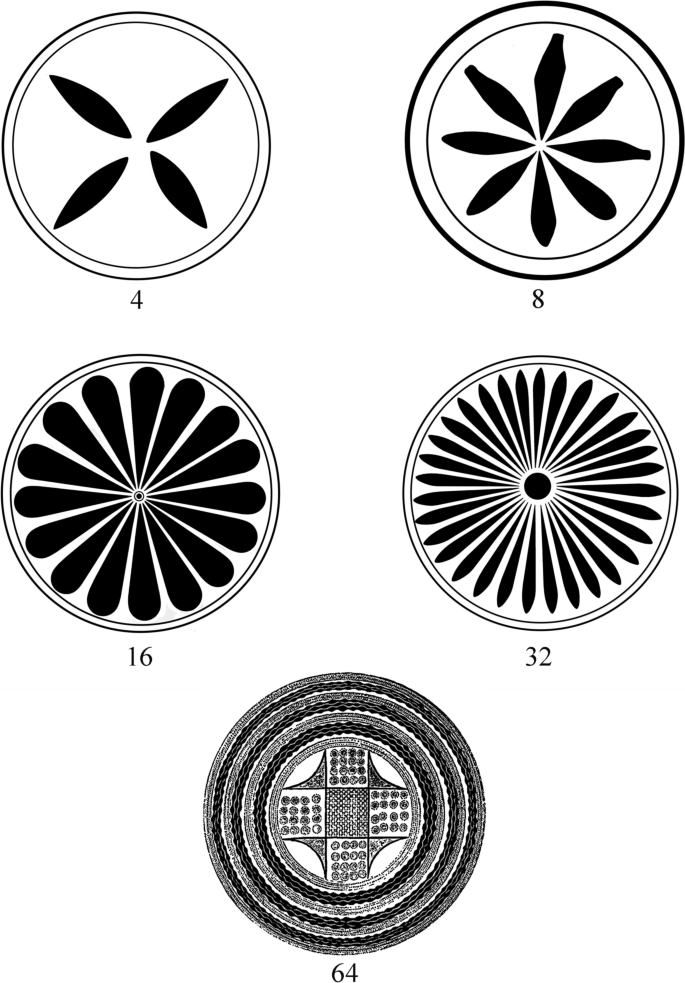

The flowers, usually placed on the bases of rounded bowls, were depicted with elongated petals. In such cases the drawing divides the circle symmetrically into four (Fig. 6:1–3), eight (Fig. 6:4–8), 16 (Fig. 7:1–2) and 32 petals (Fig. 7:3–4). In one case two flowers with eight petals were drawn one above the other on the body of a closed vessel (Fig. 6:8). In another bowl from Arpachiyah the division of the space was completely different: the base was divided into a checkerboard pattern of three rows and three columns. In four alternating squares four flowers were drawn in each of four rows, making a total of 16 flowers in each square and 64 flowers altogether (Fig. 7:5). The numbers 4, 8, 16, 32 and 64 create a mathematical series, which will be discussed below.

A meticulously executed drawing of a single large flower, depicted in a symmetrical arrangement with four or eight petals: 1. Tepe Gawra (Tobler, 1950, pl. CXI:17), 2. Tepe Gawra (Tobler, 1950, pl. CXII:20), 3. Arpachiyah (Mallowan & Cruikshank Rose, 1935, fig. 61.2), 4. Tepe Gawra (Tobler, 1950, pl. CXI:16), 5. Chagar Bazar (Mallowan, 1936, pl. II:7), 6. Tell Bagum (Hijara, 1997, pl. XCII:3), 7. Arpachiyah (Hijara, 1997, pl. LXV:441), 8. Yarim Tepe II (Merpert & Munchaev, 1987, fig. 11:7)

A meticulously executed drawing of a single large flower, depicted in a symmetrical arrangement with 16 or 32 petals, and a bowl with 64 (+ 12) flowers: 1. Arpachiyah (Mallowan & Cruikshank Rose, 1935, pl. XV), 2. Tepe Gawra (Tobler, 1950, pl. CXI:15), 3. Tepe Gawra (Tobler, 1950, pl. CX:12), 4. Arpachiyah (Mallowan & Cruikshank Rose, 1935, frontispiece), 5. Arpachiyah (Mallowan & Cruikshank Rose, 1935, pl. XVIII)

In a small number of examples a different number of petals was carefully drawn: six (Fig. 8:1–2), seven (Fig. 8:3–5), 12 (Fig. 8:6–7) and 13 (Fig. 8:8). It is possible that the numbers 6 and 12 were chosen intentionally, but in the absence of the numbers 3 and 24 we cannot suggest a geometric series here. The numbers 7 and 13 may have been chosen without special intent.

-

4.

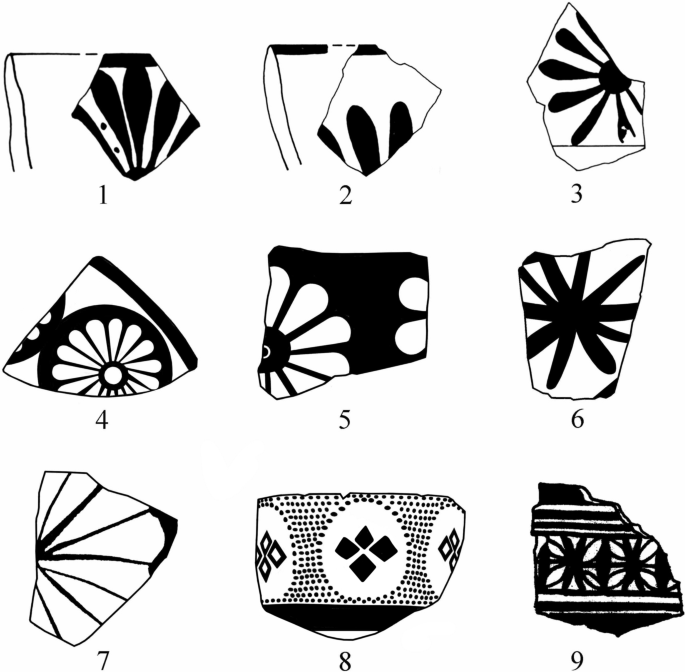

A free-hand depiction of a large flower, lacking the meticulous arrangement and quality of the previous group (Fig. 9:1–7). There are also a few examples of somewhat different flowers (Fig. 9:8–9).

-

5.

A rather sloppy drawing of a large flower on the base of a bowl (Fig. 10:1–2, 4–5) or the body of a vessel (Fig. 10:6–7). The depiction is sometimes more crowded, consisting of a number of smaller flowers (Fig. 10:3, 8–9). As in the previous group, the drawing divides the circle into 4, 8 or 16 petals, but a division into 32 petals has not been observed.

-

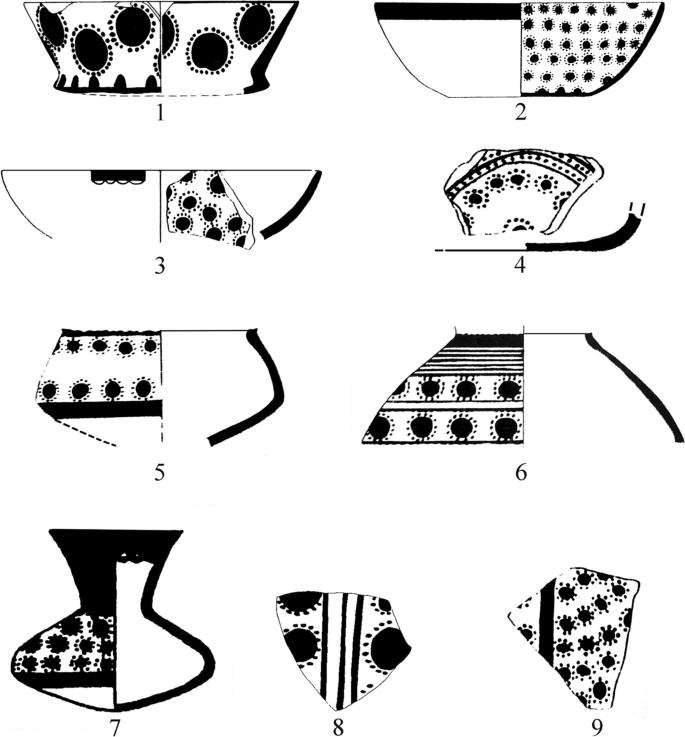

6.

Schematically drawn flowers with a dark, emphasized round center, surrounded by a circle of dots (Fig. 11). A large number of such flowers are depicted on each vessel, in various arrangements: horizontal rows (Fig. 11:2, 5–7), vertical rows (Fig. 11:8), diagonal rows (Fig. 11:9) and a concentric arrangement on the base of a bowl (Fig. 11:4). Similar flowers, with leaves and a stalk, appear in the first group (Fig. 3:1, 3, 6–7).

-

7.

Schematic flowers expressed by concentric circles of various types (Fig. 12): a black dot, an emphasized circle, an outer circle of dots and, most schematically of all, a simple dotted circle (Fig. 12:10–12). Similar flowers, with leaves and a stalk, appear in the first group (Fig. 3:2, 4–5).

A meticulously executed drawing of a single large flower, depicted in a symmetrical arrangement with six, seven, 12 or 13 petals: 1. Arpachiyah (Mallowan & Cruikshank Rose, 1935, fig. 57.1), 2. Ugarit (De Contenson, 1992, fig. 211:10), 3. Yarim Tepe III (Merpert & Munchaev, 1993, fig. 9.9:2), 4. Arpachiyah (Mallowan & Cruikshank Rose, 1935, fig. 53.2), 5. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LV:9), 6. Tepe Gawra (Tobler, 1950, pl. CX:13), 7. Tepe Gawra (Tobler, 1950, pl. CXI:14), 8. Arpachiyah (Mallowan & Cruikshank Rose, 1935, pl. XIII)

A free-hand depiction of a large flower lacking meticulous arrangement (1–7) and examples of different flowers (8–9): 1. Hama (Thuesen, 1988, pl. XV:10), 2. Hama (Thuesen, 1988, pl. XV:9), 3. Hama (Thuesen, 1988, pl. XIV:4), 4. Yarim Tepe II (Merpert & Munchaev, 1993, fig. 8.25:3), 5. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. XC:6), 6. Cavi Tarlasi (Von Wickede & Herbordt, 1988, fig. 7:10), 7. Tell Turlu (Breniquet, 1991, pl. XII:20), 8. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LV:5), 9. Tepe Gawra (Speiser, 1927, fig. 51)

Sloppy drawings of large or small flowers: 1. Arpachiyah (Mallowan & Cruikshank Rose, 1935, fig. 72:1), 2. Tepe Gawra (Tobler, 1950, pl. CXIX:72), 3. Shams ed-Din (Gustavson-Gaube, 1981, pl. III:11), 4. Cavi Tarlasi (Von Wickede & Herbordt, 1988, fig. 6:10), 5. Ugarit (De Contenson, 1992, fig. 192:3), 6. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LV:3), 7. Şirnak Valley (Erdalkιran, 2006, fig. 4:29), 8. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LV:4), 9. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LV:2)

Schematically drawn flowers with a dark, emphasized round center, surrounded by a circle of dots: 1. Yarim Tepe II (Merpert & Munchaev, 1987, fig. 18:1), 2. Arpachiyah (Hijara, 1997, pl. LI:355), 3. Arpachiyah (Hijara, 1997, pl. LXIII:426), 4. Arpachiyah (Hijara, 1997, pl. LXXIII:506), 5. Arpachiyah (Hijara, 1997, pl. XXVIII:194), 6. Arpachiyah (Hijara, 1997, pl. XXXI:223), 7. Arpachiyah (Hijara, 1997, pl. L:349), 8. Tell Amarna (Cruells, 2004, fig. 5.51:10,517), 9. Arpachiyah (Hijara, 1997, pl. XLII:297)

Schematic flowers expressed by concentric circles of various types: 1. Yarim Tepe II (Merpert & Munchaev, 1987, fig. 16:3), 2. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LV:7), 3. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LV:12), 4. Khirbet esh-Shenef (Akkermans, 1993, fig. 3.39:109), 5. Arpachiyah (Mallowan & Cruikshank Rose, 1935, fig. 67.2), 6. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. XCI:3), 7. Tell Halula (Cruells, 2013, fig. 14:1619), 8. Khirbet esh-Shenef (Akkermans, 1993, fig. 3.39:103), 9. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LV:13), 10. Umm Qseir (Hole, 2017, fig. 17.6:12), 11. Damishliyya (Akkermans, 1993, fig. 3.9:58), 12. Ugarit (De Contenson, 1992, fig. 177:13)

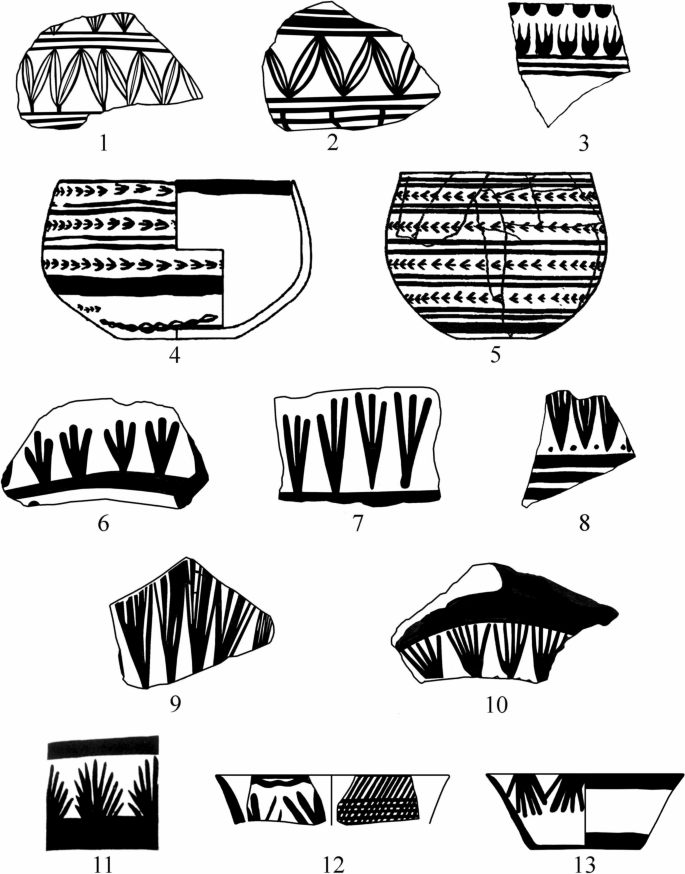

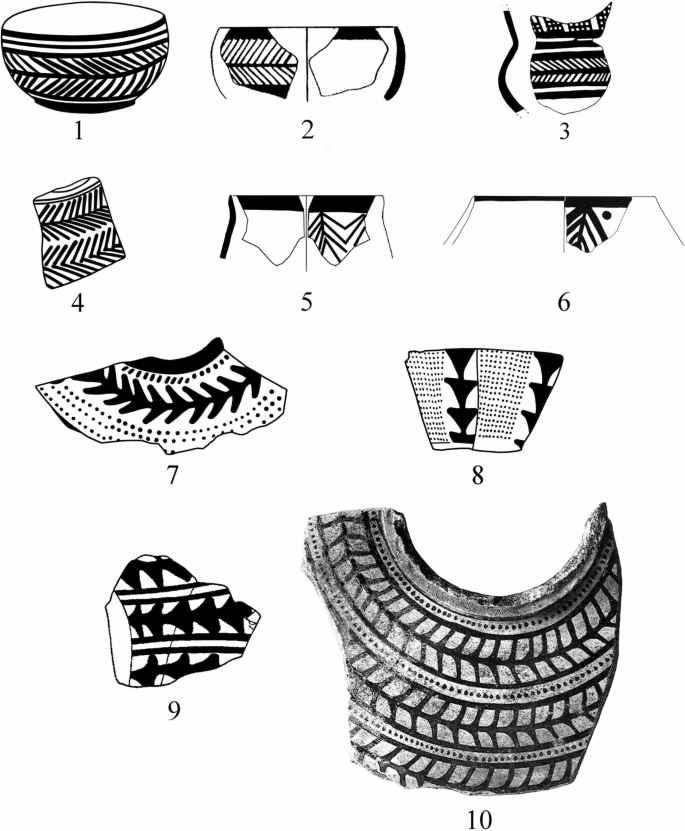

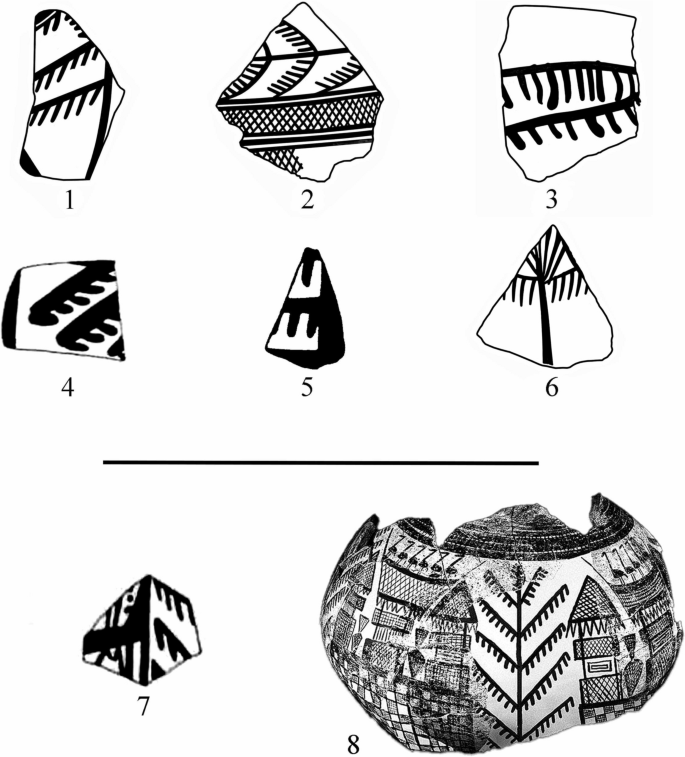

Shrubs

This is the third most common vegetal motif in Halafian painted pottery, identified on 90 examples. These are depictions of entire plants, similar to the first group of flowers but lacking the flowers. As in the previous category, the schematic nature of the depictions prevents the identification of specific plants. Three well-defined sub-groups can be seen here, together with a group of varia.

-

1.

Small seedlings in their initial stage, consisting of a sprout with two or three leaves (Fig. 13:1–5).

-

2.

Small shrubs with a larger number of leaves (Fig. 13:6–13). The leaves are long and narrow, all growing from the same spot. In one example the shrub is drawn upside down on the inner rim of a bowl (Fig. 13:13). From the aspect of perspective, when one holds the bowl and looks at its interior the plant does not appear reversed.

-

3.

Tall shrubs with a central stem and narrow leaves protruding symmetrically to the right and left. These are somewhat reminiscent of the trees in the fourth group, but the plants are more delicate, unlike the massive trees with a trunk, branches and leaves. Such shrubs are shown sometimes alone (Fig. 14:1–8), sometimes in pairs (Fig. 14:9–14) and sometimes in larger groups (Fig. 14:15–16). Some schematic depictions represent the shrub by a vertical row of two diagonal lines in the shape of the letter V (Fig. 14:8–9).

-

4.

A few individual examples, each depicted in a different style (Fig. 15).

Small seedlings (1–5) and small shrubs (6–13): 1. Yarim Tepe III (Merpert & Munchaev, 1993b, fig. 9.11:5), 2. Yarim Tepe III (Merpert & Munchaev, 1993b, fig. 9.11:1), 3. Tepe Gawra (Speiser, 1927, fig. 56), 4. Umm Qseir (Hole, 2017, 17.1:17), 5. Chagar Bazar (Mallowan, 1936, fig. 23:5), 6. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LIII:7), 7. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LIII:11), 8. Hama (Thuesen, 1988, pl. XVIII:6), 9. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LIII:10), 10. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LIII:13), 11. Arpachiyah (Mallowan & Cruikshank Rose, 1935, fig. 77:10), 12. Tell Sabi Abyad (Le Mière & Nieuwenhuyse, 1996, fig. 3.53:6), 13. Tell Halula (Cruells, 2013, fig. 6:1032)

Tall shrubs with a central stem and narrow leaves protruding symmetrically to the right and left: 1. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LXI:2), 2. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LXI:1), 3. Tell Amarna (Cruells, 2004, fig. 5.45:10,474), 4. Tell Damishliyya (Akkermans, 1993, fig. 3.9:56), 5. Tell Damishliyya (Akkermans, 1993, fig. 3.9:52), 6. Ugarit (De Contenson, 1992, fig. 225:11), 7. Shams ed-Din (Gustavson-Gaube, 1981, fig. 164), 8. Tepe Gawra (Speiser, 1927, fig. 48), 9. Tepe Gawra (Speiser, 1927, fig. 49), 10. Şirnak Valley (Erdalkιran, 2008, fig. 3:31), 11. Tell Sabi Abyad (Le Mière & Nieuwenhuyse, 1996, fig. 3.26:4), 12. Chagar Bazar (Mallowan, 1936, fig. 27:15), 13. Tell Halula (Cruells, 2013, fig. 12:1563), 14. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LXI:6), 15. Tell Sabi Abyad (Le Mière & Nieuwenhuyse, 1996, fig. 3.53:1), 16. Tell Turlu (Breniquet, 1991, pl. XIII:7)

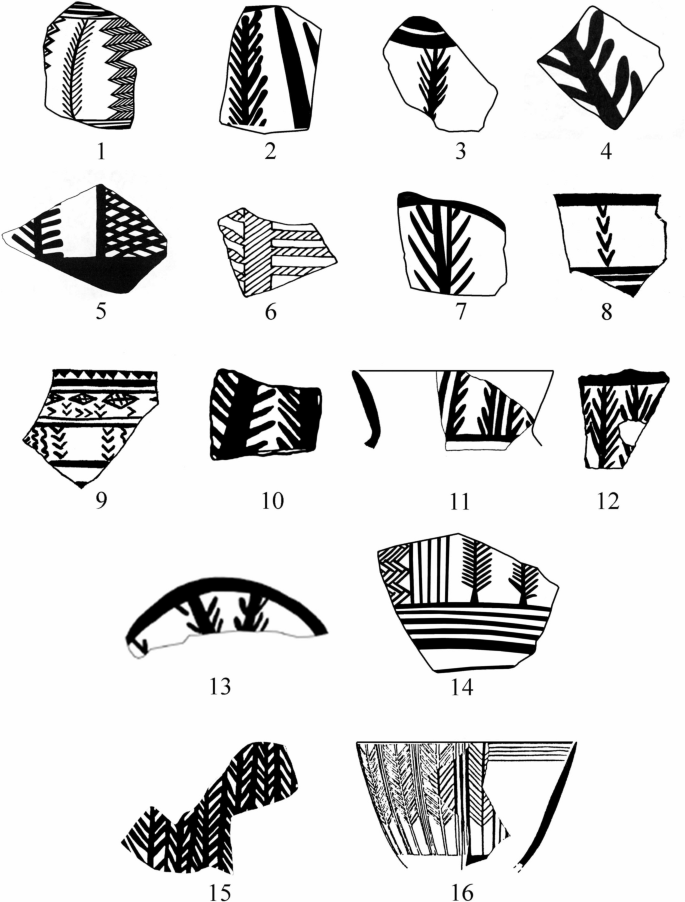

Branches

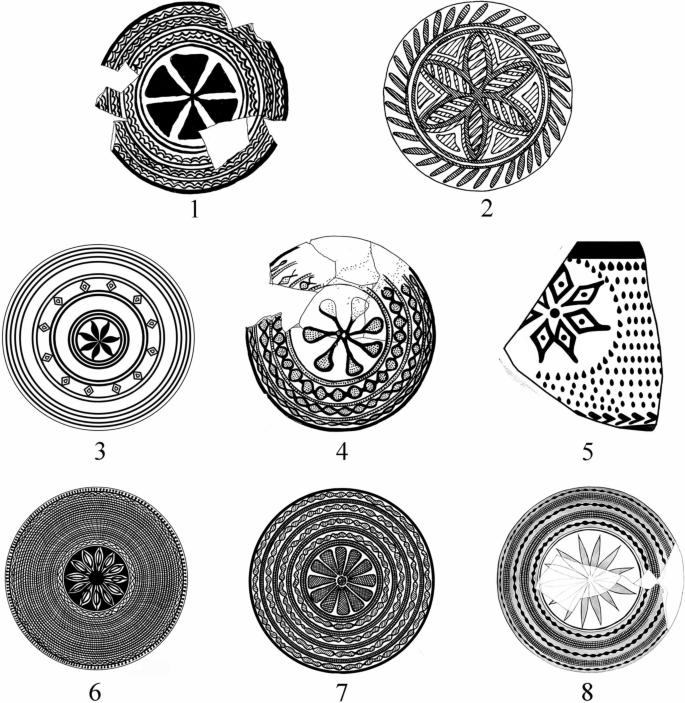

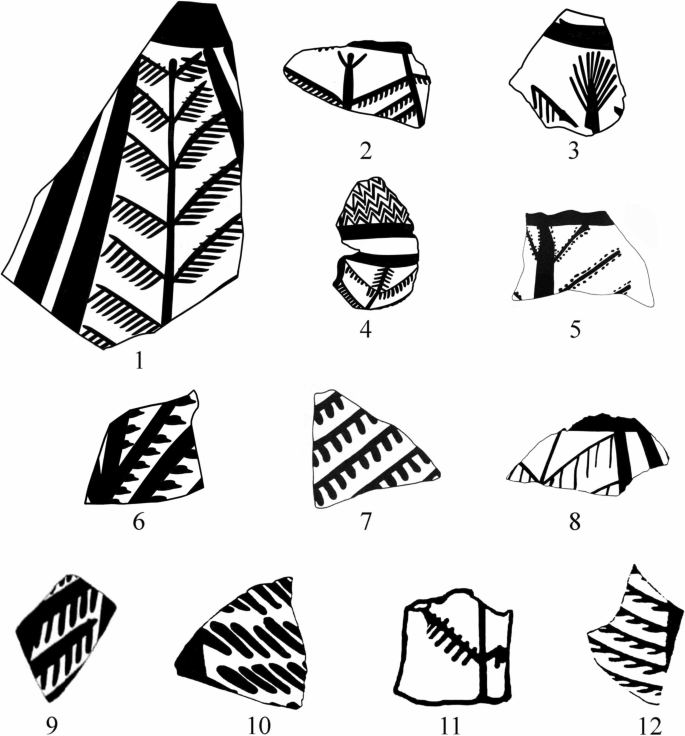

This is the second most common vegetal motif in Halafian painted pottery, identified on 291 examples. The branch seems to be detached from a shrub or tree and is a decorative element in its own right. The depictions are too schematic to enable the identification of specific plants. Five different groups can be identified.

-

1.

A branch with rounded leaves, usually depicted horizontally on the vessel (Fig. 16). The leaves are carefully drawn, sometimes with a central line that divides the leaf into two and sometimes covered with black dots. Similar leaves with black dots are known in the first group of flowers (Fig. 3:1–6, 8–9). The depictions of the leaves are sometimes so schematic that they look like an abstract geometric pattern (Fig. 16:10–11).

-

2.

A branch with narrow leaves, like a palm branch. This pattern is often designated ‘chevron’ in the reports. We have included here only depictions with a central thin branch, from which the leaves emerge. These branches are usually arranged in a horizontal strip surrounding the vessel (Fig. 17:1–4), although there are some examples in which the branches descend from top to bottom of the vessel (Fig. 17:5–6).

-

3.

Schematic depictions of leaves with a triangular outline, arranged on the vessel in horizontal or vertical lines (Fig. 17:7–9).

-

4.

Branches organized in horizontal strips on the vessel, with white leaves on a black background. Each leaf is painted in isolation and does not touch the other leaves or a central branch (Fig. 17:10).

-

5.

On some bowls symmetrical radial lines reminiscent of petals were drawn on the base. A few meticulous drawings on the bases of rounded bowls resemble flowers with eight or 16 petals. However, rather than depicting petals, these are branches with seed pods (Fig. 18:1–2). In other examples, these lines resemble the branches of the trees of the next category, as small lines protrude perpendicularly from each branch (Fig. 18:3–4). There are a few other radial depictions as well (Fig. 18:5–7).

Branches with rounded leaves: 1. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LXXI:6), 2. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LXI:5), 3. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LXI:7), 4. Chagar Bazar (Mallowan, 1936, pl. III:7), 5. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LXI:10), 6. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LIII:14), 7. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LIII:16), 8. Arpachiyah (Hijara, 1997, fig. 78:30), 9. Damishliyya (Akkermans, 1993, fig. 3.8:46), 10. Kazane Hoyuk (Bernbeck et al., 1999, fig. 10:9), 11. Tepe Gawra (Speiser, 1927, fig. 42)

Branches with narrow leaves (1–6, 10) and triangular leaves (7–9): 1. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LXVIII:9), 2. Arpachiyah (Hijara, 1997, pl. LXIX:479), 3. Tell Sabi Abyad (Akkermans, 1993, fig. 3.18:16), 4. Shams ed-Din (Gustavson-Gaube, 1981, fig. 167), 5. Tell Halula (Cruells, 2013, fig. 14:1872), 6. Hama (Thuesen, 1988, pl. XIII:12), 7. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LIV:5), 8. Yanus (Woolley, 1934, pl. XVIII), 9. Girikihaciyan (Watson & LeBlanc, 1990, fig. 4.8:4), 10. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LIV:3)

Radial patterns depicting various types of branches: 1. Tepe Gawra (Tobler, 1950, pl. CXII:18), 2. Tepe Gawra (Tobler, 1950, pl. CXII:19), 3. Arpachiyah (Mallowan & Cruikshank Rose, 1935, Fig. 77:7), 4. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LXXIII:507), 5. Cavi Tarlasi (Von Wickede & Herbordt, 1988, fig. 7:9), 6. Arpachiyah (Mallowan & Cruikshank Rose, 1935, fig. 77:6), 7. Tell Turlu (Breniquet, 1991, pl. XI:13)

Trees

This is the least common vegetal motif in Halafian painted pottery, identified on 30 examples. This group includes depictions of tall, massive trees. The tree has three components: a central trunk, lateral branches growing symmetrically to the right and left, and small branches/leaves that descend from the branches (Fig. 19). The top of the trunk is sometimes presented with its growth apex (Fig. 19:2–4). The branches usually ascend diagonally and rarely descend diagonally (Fig. 20:1–6), while the third component, small branches/leaves, almost always descend. In one example from Umm Qasr, these small branches/leaves are marked by small dots on the upper part of the tree (Fig. 19:5). In one case the tree is depicted without the lateral branches (Fig. 19:10).

Tall, massive trees: 1. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LXI:3), 2. Shams ed-Din (Gustavson-Gaube, 1981, fig. 233), 3. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LXI:4), 4. Kerküşti Höyük (Sarialtun & Erim-Özdoğan, 2011, fig. 13:4), 5. Umm Qseir (Hole & Johnson, 1986–87:215, fig. j, 6. Yanus (Woolley, 1934, pl. XVIII), 7. Damishliyya (Akkermans, 1993, fig. 3.9:55), 8. Khirbet esh-Shenef (Akkermans, 1993, fig. 3.42:140), 9. Tell Sabi Abyad (Le Mière & Nieuwenhuyse, 1996, fig. 3.53:14), 10. Khirbet esh-Shenef (Akkermans, 1993, fig. 3.37:84), 11. Şirnak Valley (Erdalkιran, 2006, fig. 3:29), 12. Tell Turlu (Breniquet, 1991, pl. XII:11)

Tall, massive trees (1–6), an animal and a tree (7), and a tree between structures (8): 1. Yanus (Woolley, 1934, pl. XVIII), 2. Kerküşti Höyük (Sarialtun & Erim-Özdoğan, 2011, fig. 13:4), 3. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. XCIX:5), 4. Tell Sabi Abyad (Le Mière & Nieuwenhuyse, 1996, fig. 3.53:13), 5. Khirbet esh-Shenef (Akkermans, 1993, fig. 3.40:121), 6. Shams ed-Din (Gustavson-Gaube, 1981, fig. 235), 7. Tell Sabi Abyad (Le Mière & Nieuwenhuyse, 1996, fig. 3.53:11), 8. Domuztepe (Carter & Campbell, 2007, fig. 6)

The depictions resemble trees of the cypress family, which are common in mountainous areas. There is, however, one example of a different type of tree, which is depicted with a central trunk and various branches to the right and left (Fig. 20:6). Unlike all the other trees, this is perhaps a palm tree.

In two examples the tree is presented in context. On a small sherd, the left-hand part of a tree is seen near an animal with a high neck (Fig. 20:7). It appears that the animal is in the forest, eating leaves from a tree. In a most interesting depiction of a tree from Domuztepe the tree was depicted between tall structures of four or five stories (Fig. 20:8). This gives an idea of the impressive height of the tree (Campbell et al., 2014). Although the central part of the tree has not been preserved, parts of the branches on the right and left, as well as the apex, clearly indicate the presence of a tree in this scene.

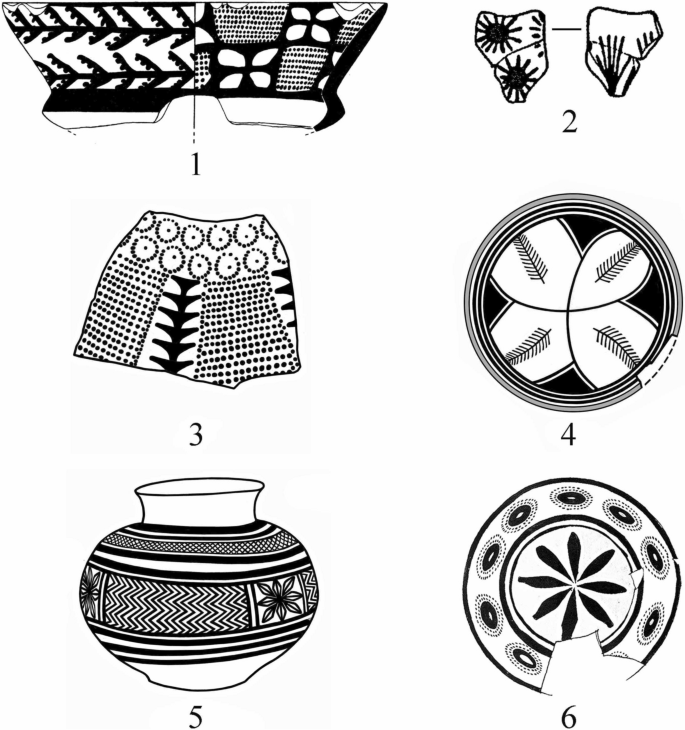

Combinations of Vegetal Motifs

There are several vessels on which two different vegetal motifs were depicted: flowers and trees (Fig. 21:1), flowers and shrubs (Fig. 21:2), flowers and branches (Figs. 8:2, 12:9, 21:3–5) and two different types of flowers (Fig. 21:6).

Combinations of vegetal motifs: 1. Yarim Tepe II (Merpert & Munchaev, 1987, fig. 19:2), 2. Girikihaciyan (Watson & LeBlanc, 1990, fig. 4.11:2), 3. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LIV:6), 4. Yarim Tepe III (Merpert & Munchaev, 1993, fig. 9.9:1), 5. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. XCIV:7), 6. Arpachiyah (Mallowan & Cruikshank Rose, 1935, pl. XVIIa)

Combinations of Flowers and Animals

In a few examples pottery vessels were decorated with flowers and animals simultaneously (Fig. 22). From the rich repertoire of vegetal motifs only flowers were chosen, but the animals are varied: birds (Fig. 22:1–2) and various wild beasts (Fig. 22:3–5). In one case a zoomorphic pottery vessel was decorated with flowers (Fig. 22:6). In another case leopard skins were depicted between branches (Fig. 22:7). Leopards were depicted on Halafian pottery from a number of sites: Arpachiyah (Mallowan & Cruikshank Rose, 1935, fig. 77:1), Chagar Bazar (Mallowan, 1936, fig. 27:1–2), Yarim Tepe II (Merpet & Munchaev, 1993b, fig. 8.4) and Domuztepe (Carter, 2012, fig. 13a). It should be noted that leopard bones were unearthed at Domuztepe (Kansa et al., 2009, table 4).

Combinations of flowers and animals: 1. Damishliyya (Akkermans, 1993, fig. 3.8:44), 2. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LVIII:10), 3. Chagar Bazar (Mallowan, 1936, fig. 27:10), 4. Tell Aqab (Davidson et al., 1981, fig. 3:3), 5. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LVI:1), 6. Umm Qseir (Tsuneki & Miyake, 1998, fig. 32:10), 7. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. XXVIII:1)

Also common is the bull’s head motif, commonly referred to as the bucranium, depicted together with various vegetal motifs such as a branch (Fig. 23:1) or flowers (Fig. 23:2–6).

Combinations of vegetal motifs and bull’s heads (1–6) and dancing humans disguised as horned animals with a horizontal strip of flowers (7): 1. Chagar Bazar (Mallowan, 1936, fig. 26:3), 2. Yarim Tepe III (Merpert & Munchaev, 1993, fig. 9.33:1), 3. Arpachiyah (Mallowan & Cruikshank Rose, 1935, fig. 76:2), 4. Yanus (Woolley, 1934, pl. XX), 5. Tell Halaf (Von Oppenheim, 1943, pl. LIX:6), 6. Domuztepe (Carter & Campbell, 2007, fig. 7)

It seems to us that combinations of vegetal motifs and human figures are rarer than vegetal depictions combined with animals. We bring here only one example of the former, a group of dancing humans disguised as horned animals with a horizontal strip of flowers above them (Fig. 23:7).

The Use of Vegetal Motifs in the Halafian Culture

The data detailed above enable us to answer the four questions raised above:

-

1.

What was chosen to be depicted? The Halafians depicted an impressive selection of vegetal motifs on their pottery, including flowers, branches, shrubs and large trees. This variety indicates awareness of the entire botanical world, from plants of different sizes to various parts of plants like branches and flowers. We do not see here typical food plants such as cereals or fruit trees, nor edible parts like seeds or fruits. Hence, the depictions clearly cannot be considered as representing cultic activities in an agricultural economy, carried out to ensure abundant crops. The decoration is clearly in the aesthetic sphere, and the motifs were chosen because of their beauty and probably their pleasing symmetry.

Within the vegetal motifs, flowers were most commonly depicted. This may also be related to their positive effect on human emotions. As frequently noted, sensory properties such as color, smell and symmetry elicit positive human emotions (Haviland-Jones et al., 2005; Hůla & Flegr, 2016).

-

2.

How common are the vegetal motifs? Few excavation reports have published statistical data on vegetal motifs, but the general impression is that they are rather rare. As presented in Table 1, the proportion of decorated sherds with vegetal motifs varies between 100 and 0%, but when they are combined their proportion is 15.3% of 5148 sherds. These frequencies do not represent the real picture, as they are biased by factors like the size of the assemblage and the awareness of the archaeologist who wrote the report. The best data on this aspect comes from the assemblage of 21,164 painted sherds from Halula, where the vegetal motifs constituted 4% (Gómez et al., 2014). In the final report of the Halula excavations the proportion of vegetal motif is 5.6%. Hence, we can assume that the average frequency of vegetal motifs on decorated sherds is around 4–6%. It is not clear, however, if the analysis of the Halula assemblage comprises all the variants that are included in our study.

-

3.

What was the distribution of the vegetal motifs? They have been found from Bagum in the east to Ugarit in the west, and from Girikihaciyan in the north to Hama in the south. The motifs were apparently part of the assemblage in every Halafian site, and where they are not reported this is probably due to the small size of a site’s assemblage.

Although the Halafian culture influenced contemporaneous cultures in other regions, in these areas the vegetal motifs appear in very small quantities. In southern Mesopotamia, an elaborate bowl painted with flowers was excavated in the Ubaid 1–2 phase at Telul eth Thalathat (Fukai et al., 1981, pl. LI:1). In the southern Levant, incised branches are known on art objects from Ha-Gosherim (Getzov, 2011, figs. 3:10, 11:b) and Neve Yam (Milevski et al., 2016) in Israel. Halafian influence on the southern Levant is also seen in pottery, sling stones, figurines and seals (Garfinkel, 1999; Milevski et al., 2016; Rosenberg, 2009; Streit & Garfinkel, 2015).

-

4.

Why were vegetal motifs introduced into human artistic expressions in this particular era? It seems to us that the decoration of Halafian pottery vessels with symmetrical patterns, dividing the surface into 4, 8, 16 and 32 repeated fields, brought cognitive awareness of the richness of flowers, shrubs, branches and trees. As food plants or edible parts of plants like seeds or fruits are not depicted, the decoration cannot be related to agricultural rites, as has been suggested for the green beads of the early Neolithic era (Bar-Yosef Mayer & Porat, 2008). We see here cognitive development in aspects relating to aesthetics and to the advance of mathematical knowledge. One might wonder if flowers and trees were planted for decorative purposes in Halafian villages, representing the beginning of gardening. The tree depicted between structures on a pottery vessel from Domuztepe (Campbell et al., 2014) may give a hint in this direction.

Flowers, Symmetry and Mathematical Thinking

The Halafian skills of symmetry and precise division of space have been noted in the literature, but have not so far been related specifically to the vegetal motifs (Brandmüller et al., 1986; Melville, 2005; Von Wickede, 1986). The depiction of flowers, especially the arrangement of the petals in the consistent use of the numbers 4, 8, 16 and 32, points to mathematical knowledge in the late prehistory of the Near East. Here we enter the field of ethnomathematics, which in the definition of D’Ambrosio, who coined the term, ‘lies on the borderline between the history of mathematics and cultural anthropology’ (D’Ambrosio, 1985). This concept has been discussed over the years by various scholars (Ascher, 2017; Ascher & Ascher, 1986; Barton, 2007). It implies that mathematical knowledge in prehistoric or non-literate communities, who do not leave written documents, can be inferred from indirect indications.

The prehistory of counting and mathematical knowledge is a fascinating topic, although scholars are usually left empty-handed when trying to deal with this issue. From time to time, scholars have dealt with the topic of counting (Marshack, 1972; Schmandt-Besserat, 1992), but no clear conclusions have been achieved regarding more complex mathematical knowledge (Bassnett et al., 2018; Damerow, 2012; Schlaudt, 2020). Only with the appearance of writing in the Sumerian culture of the ancient Near East, in the 3rd millennium BC, do texts supply undisputed data on various mathematical aspects (Mansfield & Wildberger, 2017; Robson, 2009). These texts reveal a sophisticated level of knowledge, raising the question of whether there are clues to earlier mathematical practices in the late prehistory of the Near East. The decoration of flowers on Halafian pottery clearly reflects sophisticated knowledge in the field of symmetry and in the ability to divide the circle into symmetrical units of 4, 8, 16 and 32. To these one might add the depiction of 64 flowers. These numbers are not accidental, for the following reasons:

-

1.

They were consistently depicted on Halafian pottery. While artists did occasionally paint flowers with six, seven or 13 petals symmetrically arranged around the entire circumference, these are isolated cases that are probably the result of less skilled craftsmanship.

-

2.

The use of the numbers 4, 8, 16, 32 and 64 creates a geometric sequence. There are no other systematic divisions of the circle into symmetrical units, such as the use of the numbers 3, 6, 12 and 24, that result in a geometric sequence (Fig. 24).

The arrangement of floral motifs, petals or flowers, in the geometric sequence of 4, 8, 16, 32 and 64

It is clear that the Sumerians used the sexagesimal system of numeration, which is based on the number 60 (Mansfield & Wildberger, 2017; Powell, 1972; Robson, 2009). It has been suggested that an earlier, pre-Sumerian decimal system used the number 10 as the base (Lewy, 1949). The Halafian use of the numbers 4, 8, 16 and 32 does not fit any of these systems, and may reflect an earlier and simpler level of mathematical thinking that was in use in the Near East in the 6th and 5th millennia BC.

The symmetrical decoration of Halafian pottery was not limited to flowers, and symmetry was common in the arrangement of other motifs (Brandmüller et al., 1986; Melville, 2005). The importance of symmetry in general, and in in art and mathematics in particular, is well known (Enquist & Arak, 1994; Field & Golubitsky, 2009; Locher & Nodine, 1989; Voloshinov, 1996). We argue that the development of mathematical thinking created a cognitive awareness of the symmetry evident in the vegetal world, and hence flowers, shrubs, branches and trees were chosen for depiction on elaborate Halafian pottery vessels. The extensive use of symmetrical decorations and the introduction of vegetal motifs thus go hand in hand.

The Halafian skills of symmetry and precise division of space are also reflected in the decoration of stamp seals. These prestige objects were made by professional seal cutters, sometimes on semi-precious stones, and reflect advanced mathematical ability. In the Neolithic communities of the Near East and Cyprus that preceded the Halafian culture, we see large pebbles and rounded stones incised with geometric patterns (Dikaios, 1953; Edwards, 2007; Eirikh-Rose, 2004; Garfinkel, 2014; Le Brun, 1984). Neolithic seals in the Near East were engraved with simple geometric patterns or horned animals (Akkermans & Duistermaat, 1997; Garfinkel, 2014; Von Wickede, 1990). The Halafian seals, however, display a previously unknown elaborate craftsmanship and complex geometric subdivision of the seals’ space (Carter, 2010; Von Wickede, 1990). In the same way, various elaborate tokens that appeared in this era are indicative of pre-literate accounting (Schmandt-Besserat, 1992).

Discussion

In the first part of this study we presented in a detailed manner the earliest systematic depictions of vegetal motifs in prehistoric art. Unlike the anthropomorphic and zoomorphic representations, which started at least as early as 40,000 BC, the vegetal motifs were introduced only c. 6200 BC, in the Halafian culture of Mesopotamia. Four major aspects of the vegetal motifs were clarified:

-

1.

The Halafians depicted flowers, branches, shrubs and large trees; no typical food plants such as cereals or fruit trees, nor edible parts like seeds or fruits, were chosen.

-

2.

Sherds with vegetal motifs comprised on average 15.3% of the 5148 decorated sherds examined in this study. Based on the data from Tel Halula it seems that the average frequency of vegetal motifs on decorated sherds is around 4–6%.

-

3.

The distribution of the vegetal motifs covered the entire Halafian territory.

-

4.

The vegetal motifs were introduced into human art in a period of developing advanced mathematical knowledge.

The decoration of pottery and seals in the Halafian culture reflects a high level of mathematical awareness. This should not surprise us, as by the late 6th and early 5th millennia BC early village communities had existed in the Near East for some 4000 years and had reached a high level of economic complexity. These developments are reflected in the large number of domesticated plants and animals, widespread pyrotechnology of pottery manufacture, and large architectural units of courtyard houses. The management of the various aspects of such a world led to the development of mathematical thinking in the fields of length, volume and area division, which is also reflected in Halafian pottery decoration.

The mathematical ability expressed by the division of space by flower petals sprang from a general need for arithmetical knowledge. For example, in the early village communities of the Near East the ability to make precise divisions enabled the equal sharing of crops from fields that were collectively cultivated by a number of families or the whole village.

In conclusion, we argue that a rather sophisticated mathematical knowledge can be attributed to the Halafian culture on the basis of various aspects:

-

1.

The complexity of the economy and social organization of the Near East after 4000 years of sedentary life.

-

2.

The elaborate symmetry of pottery decoration.

-

3.

The arrangement of floral motifs, petals or flowers, in the geometric sequence of 4, 8, 16, 32 and 64.

-

4.

The engraving of elaborate seals with complex geometric patterns.

-

5.

The appearance of various tokens that are indicative of pre-literate accounting.

The topic of prehistoric mathematics, which at first glance seems to be beyond the limits of our knowledge, is reflected in the Halafian pottery. Even in the absence of written evidence, we can see rather sophisticated abilities in communities of the late prehistoric Near East. It was as a result of this intellectual and cognitive awareness of mathematical aspects that vegetal motifs were introduced into human artistic expression.

References

Akkermans, P. M. M. G. (1993). Villages in the steppe: Late Neolithic settlement and subsistence in the Balikh Valley, Northern Syria. Berghahn.

Akkermans, P. M. M. G. (2000). Old and new perspectives on the origins of the Halaf culture. Subartu, 7, 43–54.

Akkermans, P. M. M. G., & Duistermaat, K. (1997). Of storage and nomads: The sealings from Late Neolithic Sabi Abyad. Syria. Paléorient, 22(2), 17–44.

Arnheim, R. (1974). Art and visual perception: A psychology of the creative eye. University of California Press.

Ascher, M. (2017). Ethnomathematics: A multicultural view of mathematical ideas. Routledge.

Ascher, M., & Ascher, R. (1986). Ethnomathematics. History of Science, 24(2), 125–144.

Baird, D., Campbell, S., & Watkins, T. (1995). Excavations at Kharabeh Shattani Vol. II. University of Edinburgh.

Barton, B. (2007). Making sense of ethnomathematics: Ethnomathematics is making sense. In G. C. Leder & H. Forgasz (Eds.), Stepping stones for the 21st century. Australasian Mathematics Education Research (pp. 225–255). Brill.

Bar-Yosef Mayer, D. E., & Porat, N. (2008). Green stone beads at the dawn of agriculture. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 105(25), 8548–8551.

Bassnett, S., Frandsen, A. C., & Hoskin, K. (2018). The unspeakable truth of accounting: On the genesis and consequences of the first ‘non-glottographic’ statement form. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 31, 2083–2107.

Belfer-Cohen, A., & Bar-Yosef, O. (1981). The Aurignacian at Hayonim Cave. Paléorient, 7(2), 19–42.

Belfer-Cohen, A., & Bar-Yosef, O. (2009). First things first: Abstract and figurative artistic expressions in the Levant. In P. G. Bahn (Ed.), An enquiring mind. Studies in honor of Alexander Marshack (pp. 25–37). Oxbow.

Bernbeck, R., Pollock, S., & Coursey, C. (1999). The Halaf settlement at Kazane Höyük: Preliminary report on the 1996 and 1997 seasons. Anatolica, 25, 109–147.

Brandmüller, J., Hrouda, B., & Von Wickede, A. (1986). Symmetry in archaeology. In I. Hargittai (Ed.), Symmetry: Unifying human understanding (pp. 783–787). Pergamon Press.

Breniquet, C. (1991). Une site Halafien de Turquie méridionale: Tell Turlu. Rapport sur la campagne de fouilles de 1962. Akkadica, 71, 1–35.

Campbell, S. (2000). The burnt house at Arpachiyah: A reexamination. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, 318, 1–40.

Campbell, S. (2007). Rethinking Halaf chronologies. Paléorient, 33(1), 103–136.

Campbell, S., Kansa, S. W., Bichener, R., & Lau, H. (2014). Burying things: Practices of cultural disposal at Late Neolithic Domuztepe, Southeast Turkey. In B. W. Porter & A. T. Boutin (Eds.), Remembering the dead in the ancient Near East: Recent contributions from bioarchaeology and mortuary archaeology (pp. 27–60). University Press of Colorado.

Carter, E. (2010). The glyptic of the middle–late Halaf period at Domuztepe, Turkey (ca. 5755–5450 BC). Paléorient, 36(1), 159–177.

Carter, E. (2012). On human and animal sacrifice in the Late Neolithic at Domuztepe. In A. Porter & G. M. Schwartz (Eds.), Sacred killing: The archaeology of sacrifice in the ancient Near East (pp. 97–124). Eisenbrauns.

Carter, E., & Campbell, S. (2007). The Domuztepe project, 2006. Kazı Sonuçları Toplantısı, 29(3), 123–136.

Copeland, L. (1979). Observations on the prehistory of the Balikh Valley, Syria, during the 7th to 4th millennia BC. Paléorient, 5, 251–275.

Cruells, W. (2004). The pottery. In Ö. Tunca & M. Molist (Eds.), Tell Amarna (Syrie) I. La période de Halaf (pp. 41–200). Peeters.

Cruells, W. (2006). The pottery. In Ö. Tunca & A.-M. Bagdho (Eds.), Chagar Bazar (Syrie). I: Les sondages préhistoriques (1999–2001) (pp. 25–79). Peeters.

Cruells, W. (2013). La cerámica Halaf en Tell Halula (VII y VI milenios cal BC): Orígenes y desarrollo. In M. M. Molist (Ed.), Tell Halula: Un poblado de los primeros agricultores en el valle del Éufrates, Siria (Vol. 2, pp. 59–211). Ministerio de Educación.

D’Ambrosio, U. (1985). Ethnomathematics and its place in the history and pedagogy of mathematics. For the Learning of Mathematics, 5(1), 44–48.

Damerow, P. (2012). The origins of writing and arithmetic. In J. Renn & M. Hyman (Eds.), The globalization of knowledge in history (pp. 153–173). Edition Open Access (reprinted in 2017).

Davidson, T. E., & McKerrell, H. (1976). Pottery analysis and Halaf period trade in the Khabur Headwaters region. Iraq, 38, 45–56.

Davidson, T. E., Watkins, T., & Peltenburg, E. J. (1981). Two seasons of excavation at Tell Aqab in the Jezirah, NE Syria. Iraq, 43, 1–18.

De Contenson, H. (1992). Préhistoire de Ras Shamra–Ougarit VIII. Editions Recherche sur les Civilisations.

Dikaios, P. (1953). Khirokitia: Final report on the excavation of a Neolithic settlement in Cyprus on behalf of the Department of Antiquities, 1936–1946. Oxford University Press.

Edwards, P. C. (2007). The context and production of incised Neolithic stones. Levant, 39, 27–33.

Eirikh-Rose, A. (2004). Geometric patterns on pebbles: Early identity symbols? In E. Peltenberg & A. Wasse (Eds.), Neolithic revolution: New perspectives on Southwest Asia in light of recent discoveries on Cyprus (pp. 145–162). Oxbow.

Enquist, M., & Arak, A. (1994). Symmetry, beauty and evolution. Nature, 372, 169–172.

Erdalkιran, M. (2008). The Halaf ceramics in Şirnak area, Turkey. In J. M. Córdoba, M. Molist, M. C. Pérez, I. Rubio, & S. Martínez (Eds.), Proceedings of the 5th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East (pp. 755–766). UMA Edicioes.

Field, M., & Golubitsky, M. (2009). Symmetry in chaos: A search for pattern in mathematics, art, and nature. Society for Industrial and Applied Mathematics.

Fukai, S., Toshio, M., & Kiyoharu, H. (1981). Telul eth-Thalathat (Vol. 1). University of Tokyo.

Garfinkel, Y., Ben-Shlomo, D., & Korn, N. (2010). Sha‘ar Hagolan. Vol. 3: Symbolic dimensions of the Yarmukian Culture: Canonization in Neolithic art. Israel Exploration Society.

Garfinkel, Y. (2014). Incised pebbles and seals. In D. Rosenberg, & Y. Garfinkel (Eds.), Sha‘ar Hagolan. Vol. 4: The ground-stone industry: Stone working at the dawn of pottery production in the Southern Levant (pp. 205–234). Israel Exploration Society.

Garfinkel, Y. (1999). Neolithic and Chalcolithic pottery of the Southern Levant. Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Garfinkel, Y. (2003). Dance at the dawn of agriculture. Texas University Press.

Garfinkel, Y. (2005). Dancing diamonds. Iran, 43, 117–133.

Garfinkel, Y. (2025). Secret societies and encrypted dancing scenes from the Halafian culture of the proto-historic Near East. World Archaeology. https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2025.2558796

Gell, A. (1998). Art and agency: An anthropological theory. Clarendon Press.

Getzov, N. (2011). Seals and figurines from the beginning of the Early Chalcolithic Period at Ha-Gosherim. Atiqot, 61, 1–26. (Hebrew).

Gombrich, E. H. (1982). The image and the eye. Phaidon.

Gómez, A., Cruells, W., & Molist, M. (2014). Late Neolithic pottery productions in Syria. Evidence from Tell Halula (Euphrates Valley): A technological approach. In M. Martinón-Torres (Ed.), Craft and science: International perspectives on archaeological ceramics (pp. 125–134). Bloomsbury Qatar Foundation.

Gómez-Bach, A., Cruells, W., Alcántara, R., Saña, M., Molist, M., & Douché, C. (2019). New excavations at Gird Banahilk, a Halafian site in Iraqi Kurdistan: Farmer and herder communities in the upper Zagros Mountains. Paléorient, 45(2), 53–66.

Gómez-Bach, A., Cruells, W., & Molist, M. (2016). Sharing spheres of interaction in the 6th millennium cal. BC: Halaf communities and beyond. Paléorient, 42(2), 117–133.

Grosman, L., Shaham, D., Valletta, F., Abadi, I., Goldgeier, H., Klein, N., Dubreuil, L., & Munro, N. D. (2017). A human face carved on a pebble from the Late Natufian site of Nahal Ein Gev II. Antiquity, 91(358), 1–5.

Gustavson-Gaube, C. (1981). Shams ed-Din Tannira: The Halafian pottery of Area A. Berytus Archaeological Studies, 29, 9–182.

Hasson, U., Hendler, T., Bashat, D. B., & Malach, R. (2001). Vase or face? A neural correlate of shape-selective grouping processes in the human brain. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 13(6), 744–753.

Haviland-Jones, J., Rosario, H. H., Wilson, P., & McGuire, T. R. (2005). An environmental approach to positive emotion: Flowers. Evolutionary Psychology, 3(1), 104–132.

Hijara, I. (1997). The Halaf period in northern Mesopotamia. Nabu Publications.

Hole, F., & Johnson. G. A. (1986–87). Umm Qseir on the Khabur: Preliminary report on the 1986 excavation. Annales Archéologiques Arabes Syriennes, 36–37, 172–220.

Hole, F. (2017). Exploring the data: The pottery of Umm Qseir. In W. Cruells, I. Mateiciucová, & O. P. Nieuwenhuyse (Eds.), Painting pots – painting people: Late Neolithic ceramics in ancient Mesopotamia (pp. 186–200). Oxbow.

Hůla, M., & Flegr, J. (2016). What flowers do we like? The influence of shape and color on the rating of flower beauty. PeerJ, 4, Article e2106. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2106

İpek, B. (2019). Figural motifs on Halaf pottery: An iconographical study of Late Neolithic society in northern Mesopotamia. M.A. thesis, Bilkent University.

Kansa, S. W., Kennedy, A., Campbell, S., & Carter, E. (2009). Resource exploitation at late Neolithic Domuztepe: Faunal and botanical evidence. Current Anthropology, 50(6), 897–914.

Kennedy, J. M. (1974). A psychology of picture perception. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

LeBlanc, S. A., & Watson, P. J. (1973). A comparative statistical analysis of painted pottery from seven Halafian sites. Paléorient, 1(1), 117–133.

Le Brun, A. (1984). Fouilles récentes à Khirokitia (Chypre): 1977–1981. Éditions Recherche sur les Civilisations.

Le Mière, M., & Nieuwenhuyse, O. (1996). The prehistoric pottery. In P. M. M. G. Akkermans (Ed.), Tell Sabi Abyad: Late Neolithic settlement. Report on the excavations of the University of Amsterdam (1988) and the National Museum of Antiquities Leiden (1991–1993) in Syria (pp. 119–284). Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te Istanbul.

Lewy, H. (1949). Origin and development of the sexagesimal system of numeration. Journal of the American Oriental Society, 69, 1–11.

Locher, P., & Nodine, C. (1989). The perceptual value of symmetry. Symmetry, 2, 475–484.

Mallowan, M. E. L. (1936). Excavations at Tall Chagar Bazar and an archaeological survey of the Habur region 1934–5. Iraq, 3, 1–59.

Mallowan, M. E. L., & Cruikshank Rose, J. (1935). Excavations at Tall Arpachiyah, 1933. Iraq, 2, 1–178.

Mansfield, D. F., & Wildberger, N. J. (2017). Plimpton 322 is Babylonian exact sexagesimal trigonometry. Historia Mathematica, 44, 395–419.

Marshack, A. (1972). Upper Paleolithic notation and symbol. Science, 178(4063), 817–828.

Marshack, A. (1991). The roots of civilization: The cognitive beginnings of man’s first art, symbol and notation. Moyer Bell.

Matthers, J. (1978). Tell Rifa‘at 1977: Preliminary report of an archaeological survey. Iraq, 40, 119–162.

Melville, D. J. (2005). Aspects of symmetry in Arpachiyah pottery. In R. Sarhangi & R. V. Moody (Eds.), Proceedings of Renaissance Banff: Mathematics, music, art, culture (pp. 131–136). Plain Book Manufacturing.

Merpert, N. Y., & Munchaev, R. M. (1987). The earliest levels at Yarim Tepe I and Yarim Tepe II in northern Iraq. Iraq, 49, 1–36.

Merpert, N. Y., & Munchaev, R. M. (1993a). Yarim Tepe II: The Halaf levels. In N. Yoffee & J. J. Clark (Eds.), Early stages in the evolution of Mesopotamian civilization: Soviet excavations in northern Iraq (pp. 129–162). University of Arizona Press.

Merpert, N. Y., & Munchaev, R. M. (1993b). Yarim Tepe III: The Halaf levels. In N. Yoffee & J. J. Clark (Eds.), Early stages in the evolution of Mesopotamian civilization: Soviet excavations in northern Iraq (pp. 163–206). University of Arizona Press.

Milevski, I., Getzov, N., Galili, E., Yaroshevich, A., & Horwitz, L. K. (2016). Iconographic motifs from the 6th–5th millennia BC in the Levant and Mesopotamia: Clues for cultural connections and existence of an interaction sphere. Paléorient, 42(2), 135–149.

Nadel, D., Danin, A., Power, R. C., Rosen, A. M., Bocquentin, F., Tsatskin, A., Rosenberg, D., Yeshurun, R., Weissbrod, L., Rebollo, N. R., & Barzilai, O. (2013). Earliest floral grave lining from 13,700–11,700-y-old Natufian burials at Raqefet Cave, Mt. Carmel, Israel. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 110(29), 11774–11778.

Nieuwenhuyse, O. P. (2007). Plain and painted pottery. The rise of Neolithic ceramics styles on the Syrian and northern Syrian plains. Brepols.

Nieuwenhuyse, O., Odaka, T., Kaneda, A., Mühl, S., Rasheed, K., & Altaweel, M. (2016). Revisiting Tell Begum: A prehistoric site in the Shahrizor plain, Iraqi Kurdistan. Iraq, 78, 103–135.

Palmer, S. E., Schloss, K. B., & Sammartino, J. (2013). Visual aesthetics and human preference. Annual Review of Psychology, 64(1), 77–107.

Powell, M. A. (1972). The origin of the sexagesimal system: The interaction of language and writing. Visible Language, 4, 5–18.

Robson, E. (2009). Mathematics in ancient Iraq: A social history. Princeton University Press.

Rollefson, G. O. (2008). Charming lives: Human and animal figurines in the Late Epipaleolithic and Early Neolithic periods in the greater Levant and eastern Anatolia. In J.-P. Bocquet-Appel & O. Bar-Yosef (Eds.), The Neolithic demographic transition and its consequences (pp. 387–416). Springer.

Rosenberg, D. (2009). Flying stones: The slingstones of the Wadi Rabah culture of the Southern Levant. Paléorient, 35(2), 99–112.

Rubin, E. (1915). Synsoplevede figurer: Studier i psykologisk analyse [Perceived figures: studies in psychological analysis]. Nordisk forlag.

Sarialtun, S., & Erim-Özdoğan, A. (2011). Studies on the Halaf pottery of the Kerküşti Höyük. Anatolia Antiqua. Eski Anadolu, 19(1), 39–52.

Schlaudt, O. (2020). Type and token in the prehistoric origins of numbers. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 30, 629–646.

Schmandt-Besserat, D. (1992). Before writing: From counting to cuneiform. University of Texas Press.

Schmandt-Besserat, D. (2013). Symbols at ‘Ain Ghazal. ‘Ain Ghazal excavation reports vol. 3. Ex Oriente.

Sommer, J. D. (1999). The Shanidar IV ‘flower burial’: A re-evaluation of Neanderthal burial ritual. Cambridge Archaeological Journal, 9(1), 127–129.

Spataro, M., & Fletcher, A. (2010). Centralisation or regional identity in the Halaf period? Examining interactions within fine painted ware production. Paléorient, 36(2), 91–116.

Speiser, E. A. (1927). Preliminary excavations at Tepe Gawra. Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research, 9, 17–94.

Stein, G. (2009). Tell Zeidan (2008). Oriental Institute Annual Report, 2008–2009, 126–137.

Streit, K., & Garfinkel, Y. (2015). Horned figurines made of stone from the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods and the domestication of sheep and goat. Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 147, 39–48.

Thuesen, I. (1988). Hama: The pre- and protohistoric periods. Nationalmuseet.

Tobler, A. J. (1950). Excavations at Tepe Gawra (Vol. II). University of Philadelphia Press.

Todorović, D. (2020). What are visual illusions? Perception, 49(11), 1128–1199.

Tsuneki, A., & Miyake, Y. (1998). Excavations at Tell Umm Qseir in middle Khabur valley, North Syria. Report of the 1996 season. University of Tsukuba.

Voloshinov, A. V. (1996). Symmetry as a superprinciple of science and art. Leonardo, 29, 109–113.

Von Oppenheim, M. F. (1943). Tell Halaf 1: Die praehistorischen funde. W. de Gruyter.

Von Wickede, A. (1986). Die ornamentik der Tell Halaf-Keramik, ein beitrag zu ihrer typologie. Acta Praehistorica et Archaeologica, 18, 7–32.

Von Wickede, A. V. (1990). Prähistorische stempelglyptik in Vorderasien. Profil-Verlag.

Von Wickede, A. V., & Herbordt, S. (1988). Çavi Tarlası: Bericht über die Ausgrabungskampagnen 1983–1984. Istanbuler Mitteilungen, 38, 5–35.

Wade, N. (1982). The art and science of visual illusions. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Watson, P. J. (1983a). The Halafian culture: A review and synthesis. In T. Cuyler Young, P. E. L. Smith, & P. Mortensen (Eds.), The Hilly Flanks and beyond: Essays on the prehistory of southwestern Asia presented to Robert J. Braidwood (pp. 231–250). Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

Watson, P. J., & LeBlanc, S. A. (1990). Girikihaciyan: A Halafian site in southeastern Turkey. Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, UCAL.

Watson, P. J. (1983b). The soundings at Banahilk. In L. Braidwood, R. Braidwood, B. Howe, C. Reed, & P. J. Watson (Eds.), Prehistoric archaeology along the Zagros flanks (pp. 545–614). Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

Woolley, C. L. (1934). The prehistoric pottery of Carchemish. Iraq, 1, 146–162.

Yizraeli-Noy, T. (1999). The human figure in prehistoric art in the Land of Israel. Israel Museum and the Israel Exploration Society. (In Hebrew.)