Why Lean 4 replaced OCaml as my Primary Language

programming_languages code theorem_proving perspectives

As I was reading Hacker News today, I happened to stumble upon an article titled "Why I Chose OCaml as my Primary Language".

This was a particularly interesting read for me: over the past few years, I have been gradually transitioning1 my primary language away from OCaml to another, newer, and hotter, language: Lean!2, and while I could understand why the author had chosen OCaml, I'm not sure I personally would make that decision.

Given the article waxes poetic on the positive tenets of OCaml, I figured it might also be interesting to hear the other side of the story — Why you might not want OCaml to be your primary language — and from an experienced and prolific3 former OCaml dev (and chair of the OCaml workshop for this year~).

In the rest of this blog post, I'm going to walk through a few pain points I've had with OCaml over the past half a decade hacking on the language, and why, in the end, they've lead me to shift to other langauges, as an added bonus, for each one, I'll also give a taster about how these problems are solved in Lean, and allude to why I'm so excited about it.

My goal with this article is not to needlessly rag on OCaml: I've invested3 a considerable amount of effort into OCaml, and I certainly look very fondly upon my time with it. My hope in pointing out these issues is both to excite the wider community about newer programming languages such as Lean, and also give the OCaml community some spotlights on areas that could be improved!

Without further ado, let's dive straight in!

Issue no. 1: A philosophy of WYSIWYG and a lack of optimisations

An important aspect of OCaml that newcomers might want to bear in mind is that it is a language and community that prides themselves on being "unsurprising", and this reflects in a philosophy of WYSIWY.

The key guiding principle across OCaml code is that it is very easy to reason about, and a seasoned OCaml dev can quickly tell you exactly how a given OCaml function behaves at runtime, its performance and how it allocates memory, etc.

let List.iter f =

function

| [] -> () (* no alloc *)

| h :: t -> f h; List.iter f t (* no alloc *)

let sum ls =

let sum = { contents = 0 } in (* alloc (1 block) *)

let f x = sum := !sum + x in (* alloc (closure) *)

List.iter f ls; (* no alloc *)

a.contents (* no alloc *)

For example, just by looking at the above block of code, we can instantly tell that it allocates one block of memory and one closure on the heap.

This simplified model means that the runtime performance of code is very predictable, and it's easy to manually optimise code, but…

This means as a developer you alone are entirely responsible for making your code go fast, and sometimes this can mean obscuring the logic of your program in the quest for performance.

As a slightly more concrete example, consider the following function, to calculate the both the sum of a list and increment each value by its index:

let incr_sum ls =

let f = (fun (sum, i) vl -> (* alloc (closure) *)

let sum = sum + vl in

let vl = vl + i in

let acc = (sum, i + 1) in (* alloc (tuple) *)

(vl, acc) (* alloc (tuple) *)

)

let (ls, (sum, _len)) ==

List.fold_map ls (0,0) in (* alloc (list + tuple) *)

(ls, sum) (* alloc (tuple) *)

I've written it out in an expanded form to make the allocations clear, but if I were really code-golfing, I'd probably write it in my own code in the following simplified form:

let incr_sum ls =

let open Pair in

let update vl =

Fun.flip (map_same2 (+)) (vl, 1) &&& snd_map ((+) vl) in

List.fold_map (Fun.flip update) (0,0) ls

|> map_fst fst

|> swap

Who said only Haskell programs could be unreadable4. Anyway, that being said, from a performance perspective, this implementation is not ideal because it allocates a lot (doubly so for my simplified version) with intermediate tuples and closures.

If memory were to become a constraint, then, as the OCaml compiler itself is very conservative in its optimisations5, we would be forced to come back to this function and manually rewrite it in order to get the desired allocation patterns, for example:

let incr_sum ls =

let i = ref 0 in (* alloc (block) *)

let sum = ref 0 in (* alloc (block) *)

let f = (fun vl -> (* alloc (closure) *)

i := !i + 1;

sum := !sum + vl;

vl + (!i - 1) (* no allocs in hot-path *)

) in

let ls = List.map f ls in (* alloc (list) *)

(ls, !sum) (* alloc (tuple) *)

In this case, if you come from an imperative background, then maybe this version of the program looks "better" for you, but in larger functional programs, building up such functional pipelines leads to more idiomatic and shorter code and as such is quite ubiquitous if you are an experienced OCaml dev.

The main point I'm making here is that, from an individual developer's perspective, I'm forced to strike a compromise between concisely expressing my intent (i.e computing this fold over a list), and obtaining high performance. In a vacuum, these compromises might be okay, but they also come with a cost of an increased maintenance burden.

Comparison to Lean

Finally, let me talk about how this differs in Lean.

As a newer language, it is harder to give any strong claims w.r.t the direction of the community, currently as far as I am aware, the compiler itself doesn't perform any radical optimisations, but the language itself makes up for this with a) more memory reuse (thanks to it's clever reference-counting with memory reuse algorithm Perceus), and b) thanks to a tower of macro-based abstractions that allow an extensible form of optimisations while still compiling down to a purely functional langauge:

def incr_sum (ls: List Int) : List Int × Int := Id.run $ do

let mut sum := 0

let mut res := #[]

for (vl, i) in ls.zipIdx do

sum := sum + 1

res := res.push (vl + i)

return (res.toList, sum)

Admittedly the abstractions in the above code probably make it a bit slower than the comparable OCaml one, but the nice thing about Lean's metaprogramming support is that in theory, we could incrementally introduce our own optimisations into the pipeline in the future as needed, but we'll come on to macros in a bit.

Issue no. 2: A slow and conservative release cycle

Branching out from the conservative nature of the language itself, this same philosophy of being conservative and backwards-compatible extends in some sense to the compiler ecosystem of the language itself. OCaml is an amazingly stable langauge, and major kudos have to be given to the community for insisting on such high standards for the ecosystem:

You can almost bet that code from more than a decade ago will run on the latest OCaml compiler, with minimal changes, if at all.

While this is great for ensuring the utility of your code over time, a sad consequence of this is that the language evolves at a very slow pace, and this extends even to things such as the standard library.

Consider this thread of adding dynamic arrays – that is, an array datastructure with O(1) access and resizable allocation:

type 'a t (* dynamic array *)

val alloc: int -> 'a t (* alloc *)

val (.[]): 'a t -> int -> 'a (* O(1) get *)

val (.[]<-): 'a t -> int -> 'a -> unit (* O(1) set *)

val push: 'a t -> 'a -> unit (* realloc (if needed) *)

This was initially proposed back in 2019 (6 years ago !!), by a fresh-eyed newcomer to the community:

The PR very quickly succumbed to orthogonal discussions of naming and was eventually closed.

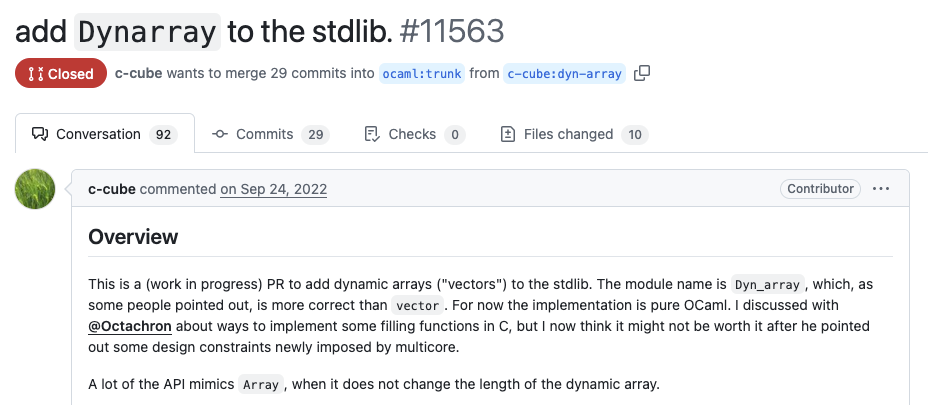

Three years later, another PR was created in a second attempt but also fared the same fate:

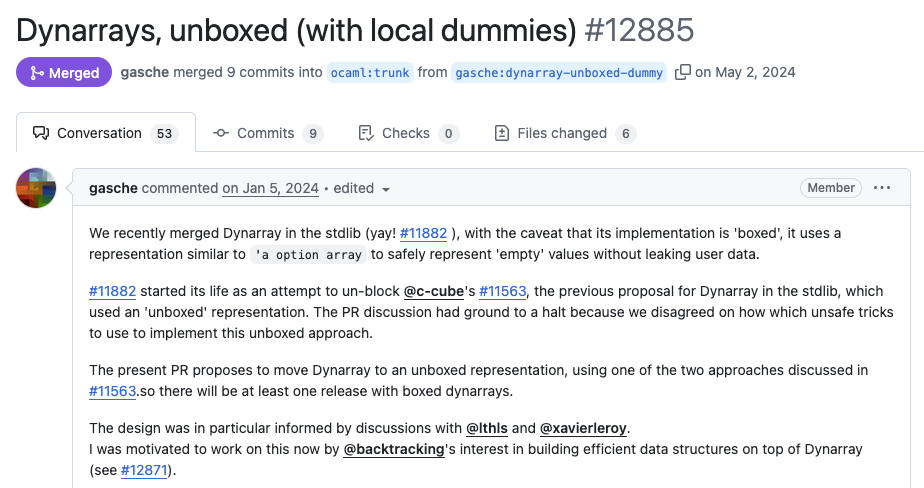

It was only last year, that this long saga was finally concluded, and dynamic arrays joined the stdlib:

Now, there were legitimate reasons for the level of caution and discussions that the community took to introduce even such a simple datastructure to the language: given its focus on backwards compatibility, any introduction to the standard library would likely continue to have to be maintained for the forseeable future, so it was critically important to move carefully here.

Again, to stress the point, OCaml's strong commitment to backwards comparability, is genuinely and truly one of the most impressive features of the language, but you can also imagine that as a developer interested in extending and exploring new abstractions for their langauge of choice, this can be a bit of a dampener.

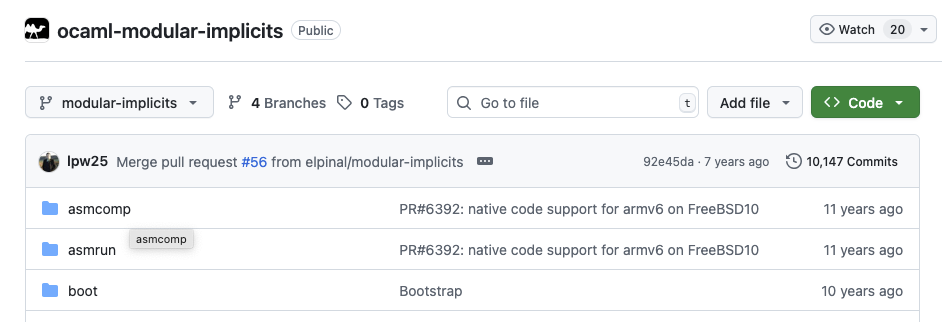

Features such as modular implicits, an OCaml-specific variant of type-classes have been being discussed for several years now, and are unlikely to be deployed anytime in the near future:

Comparison to Lean

Finally, to contrast to Lean: as the new and scrappy kid on the block, the Lean language developers a lot more open to moving fast and breaking stuff. This has the consequence of meaning that often updating to the latest version of Lean will break your code, and there's an entire cottage industry of developers dedicated to fixing core libraries when that happens but the cool thing is that as a developer and user of the language, you have a very real capacity to get your changes incorporated into the language.

Issue no. 4: An opinionated build system

This is a relatively minor point, but it's caused me some pain in the past, so I figured it's worth mentioning.

OCaml's build systems have evolved a lot over the years, and it has taken some time to converge upon a robust and efficient solution that works for most people. Thanks to the folks at Jane Street, who developed the Dune build system, OCaml now has a really nice and consistent story w.r.t building.

Simply write a dune file, which uses a pretty uncontroversial and simple s-expression-based syntax to describe your project and its dependencies, and voila, your project can be built with minimal fuss~

(library

(name lib)

(deps ...))

…that is assuming you're not straying too far from the "happy path".

That is, dune works well for most OCaml projects, but, as a self-titled "opinionated build manager", deliberately provides a restricted set of possible build actions — if you want to do things like generating text as part of your build and so on and so forth, you'll very quickly find yourself running into walls.

Dune supports a number of extensions beyond pure OCaml, such as supporting Ctype-based projects with FFI, and C builds, and even some Rocq build support, but these extensions are all driven mostly by what Jane Street wants or uses, and straying too far from the beaten path will lead to pain.

Comparison to Lean

A comparison to Lean isn't entirely fair here, as Lean, given its age is still figuring out the exact build process it wants to use, and not to mention, it doesn't quite have as robust a story for package management as OCaml does (I run into a lot of problems where using wrong versions can cause unrelated packages to fail to build).

That being said, I still wanted to take a second to point out a little thing that I thought was really cool:

Lean's Lake build files are written in Lean itself!

So, this might not be the case forever, it seems like there's a push to move towards TOML files (at least from reading the documentation recently), but at the time of writing, one format for the build description of Lean projects is simply as a Lean file that imports a build DSL:

import Lake

open Lean Lake DSL

require mathlib from git

"https://github.com/leanprover-community/mathlib4.git"

require betterfind from "./BetterFind"

package probability where

lean_lib BallsInBins where

Naturally, because Lakefiles are simply Lean code itself, and thanks to the extensibility of the metaprogramming facilities in Lean, this offers an amazing deal of flexibility in constructing your own extensions to the build process, and I've even managed to single-handedly over a weekend recreate several features I've needed from Dune such as a restricted equivalent of OCaml's ctypes and ctypes-build support, or even use it to generate LaTeX pdfs.

Conclusion

With that I've reached the end of the biggest pain-points I've had with OCaml over my time with it. Hopefully, it's given you an alternative perspective on the language and some of its features that you might not like.

I think an arguable caveat to all of these criticisms is that in some sense, they're only a problem if you're a solo-developer — the WYSIWY nature of the language, the restrictive metaprogramming support, the constrained build system and runtime representations are all features that, if you're a company looking for stable and consistent code, are arguably positives. This would certainly explain the popularity of OCaml in companies like Jane Street and Ahrefs, where unexciting and boring code is a distinct positive (no-one wants to be the one to explain why you just lost a bajillion dollars because your macro had a typo).

That being said, if you're a developer who wants to exploit the multiplicative factor of a truly flexible and extensible programming language with state of the art features from the cutting-edge of PL research, then maybe give Lean a whirl!

Plus, as an extra benefit, you might even end up contributing to state of the art mathematics research~