As an undergrad I learned a lot about partial derivatives in physics classes. But they told us rules as needed, without proving them. This rule completely freaked me out. If derivatives are kinda like fractions, shouldn’t this equal 1?

Let me show you why it’s -1.

First, consider an example:

This example shows that the identity is not crazy. But in fact it

holds the key to the general proof! Since is a coordinate system we can assume without loss of generality that

. At any point we can approximate

to first order as

for some constants

. But for derivatives the constant

doesn’t matter, so we can assume it’s zero.

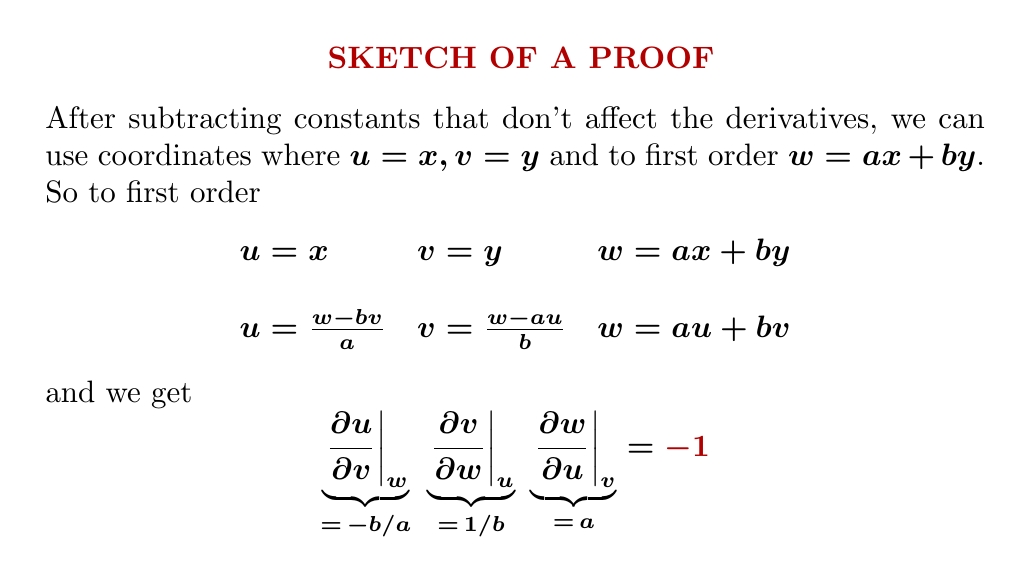

Then just compute!

There’s also a proof using differential forms that you might like

better. You can see it here, along with an application to

thermodynamics:

But this still leaves us yearning for more intuition — and for me, at least, a more symmetrical, conceptual proof. Over on Twitter, someone named

Postdoc/cake provided some intuition using the same example from thermodynamics:

Using physics intuition to get the minus sign:

- increasing temperature at const volume = more pressure (gas pushes out more)

- increasing temperature at const pressure = increasing volume (ditto)

- increasing pressure at const temperature = decreasing volume (you push in more)

Jules Jacobs gave the symmetrical, conceptual proof that I was dreaming of:

This proof is more sophisticated than my simple argument, but it’s very pretty, and it generalizes to higher dimensions in ways that’d be hard to guess otherwise.

He uses some tricks that deserve explanation. As I’d hoped, the minus signs come from the anticommutativity of the wedge product of 1-forms, e.g.

But what lets us divide quantities like this? Remember, are all functions on the plane, so

are 1-forms on the plane. And since the space of 2-forms at a point in the plane is 1-dimensional, we can divide them! After all, given two vectors in a 1d vector space, the first is always some number times the second, as long as the second is nonzero. So we can define their ratio to be that number.

For Jacobs’ argument, we also need that these ratios obey rules like

But this is easy to check: whenever are vectors in a 1-dimensional vector space, division obeys the above rule. To put it in fancy language, nonzero vectors in any 1-dimensional real vector space form a ‘torsor’ for the multiplicative group of nonzero real numbers:

• John Baez, Torsors made easy.

Finally, Jules used this sort of fact:

Actually he forgot to write down this particular equation at the top of his short proof—but he wrote down three others of the same form, and they all work the same way. Why are they true?

I claim this equation is true at some point of the plane whenever are smooth functions on the plane and

doesn’t vanish at that point. Let’s see why!

First of all, by the inverse function theorem, if at some point in the plane, the functions

and

serve as coordinates in some neighborhood of that point. In this case we can work out

in terms of these coordinates, and we get

or more precisely

Thus

so

as desired!

This entry was posted on Monday, September 13th, 2021 at 4:21 pm and is filed under mathematics, physics. You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed. You can leave a response, or trackback from your own site.