Please like, share, comment, and subscribe. It helps grow the newsletter and podcast without a financial contribution on your part. Anything is very much appreciated. And thank you, as always, for reading and listening.

Jimmy Alfonso Licon is a philosophy professor at Arizona State University working on ignorance, ethics, cooperation and God. Before that, he taught at University of Maryland, Georgetown, and Towson University. He loves classic rock and Western, movies, and combat sports. He lives with his wife, a prosecutor, and family at the foot of the Superstition Mountains. He also abides.

This piece is forthcoming in the higher education trade publication Faculty Focus.

When ChatGPT first arrived, many faculty reacted with horror. If an algorithm could write a plausible essay in seconds, what would become of higher education and philosophy, those disciplines that, at their best, are built around slow thought and crafted prose? But over the past two years, I’ve arrived at a different conclusion: the problem is not that AI can write for our students better than most of them could have on their own, but that it forces us to clarify what learning is actually for and how to instill in in our students.

In my philosophy classes at ASU, I’ve developed several AI-integrated assignments designed to do precisely that. They do not attempt to detect or prevent AI use. Instead, in the case of these specific assignments they require students to use it under conditions that make cheating (nearly) pointless and learning inevitable. Each assignment treats AI as a foil rather than a threat: an endlessly patient interlocutor that can absorb reputational risk, provoke explanation, and invite students to deepen their learning and understanding.

These activities build on two mutual insights. First, as David Duran’s review of decades of research shows, students learn more deeply when they teach by explaining, questioning, and clarifying for others. Second, as Andrew Vonasch and colleagues demonstrate, people are highly sensitive to their reputation to such a degree that they would endure pain, disgust, or even death rather than be seen as highly immoral. These insights reveal both the problem and the opportunity: students stay silent or disengaged not because they don’t care, but because they care too much about looking bad and the kinds of (social) costs that could be and sometimes are visited on the offending student. AI, being incapable of judgment or memory, provides a lower risk avenue to participate and share their views.

Philosophy is the rigorous and systematic practice of inquiry. However, practice requires vulnerability and the willingness to be wrong in front of others. When students risk public embarrassment, they risk the social currency that allows them to cooperate, belong, and be respected. In a reputation-driven classroom, silence is often the rational choice. While, in contrast, large language models have no ego and so can absorb the cost of students’ trial and error. The LLM becomes a reputational buffer that allows students to more freely speak their mind and explore positions with less risk of social retribution turning AI into a form of pedagogical prosthetic for intellectual risk taking.

Below are the cornerstone assignments that make use of AI as a catalyst. Each one integrates reputational psychology and the learning-by-teaching into its design.

1. Clap Back: Debating the Digital Devil’s Advocate

In Clap Back, students spar with a customized AI trained to defend a specific philosophical position—skepticism, utilitarianism, nihilism, theism, you name it. The role of AI is to argue tirelessly and consistently while the student is tasked with exposing errors in its reasoning and defending a counterposition. Students work individually or in small teams, annotate their transcripts, and submit a meta-reflection analyzing where the debate turned. And we sometimes hold in-class tournaments, where groups compete to see who “defeated” their AI most convincingly, judged by peers and professor.

This assignment lowers reputational stakes while sharpening philosophical skills. Students who might hesitate to challenge a classmate will freely push back against a machine that cannot feel embarrassment or condescension. The social threat of “looking stupid” evaporates, replaced by the intellectual pleasure of winning an argument that matters with the learning benefit here coming from having to explain and respond their views to other students and the AI. Using this assignment experimentally across several classes and semesters has been revealing increasing discussion participation by almost double. It is clear so far that students very much enjoy the discussion when it is less socially risky.

2. Teaching for Botmerica: Learning by Teaching Machines

This assignment is built directly on the research tradition Duran reviews: that students learn most effectively when they teach. In Teaching for Botmerica, students are paired with a deliberately “ignorant” LLM pre-trained to misunderstand a key philosophical concept—say, moral luck, validity, or the mind-body problem. The student’s job is to teach the AI step by step, using examples, counterexamples, and clarifications. They document the exchange and furnish a link for the professor to review.

The genius of this task, pedagogically, is that it forces metacognition. Students cannot teach what they do not understand. When the model parrots back a half-correct definition, it forces students to learn enough about the material to teach the bot by revising, rephrasing, and testing until the AI understands (so to speak). This dynamic mirrors Duran’s finding that learning-by-teaching is strongest when the “learner” (the AI) is interactive rather than passive. The questioning and feedback cycles consolidate understanding.

3. Reverse Office Hours: Students in the Hot Seat

In this exercise, students take over office hours—but the professor becomes the questioner. Each week, a group meets with me to “teach” that week’s material. They know I will press them using the Socratic method: Why does Mill think that? What problem is Kant solving here? Where does the argument fail? Their performance shapes the next lecture, where I incorporate their insights (and missteps) into the discussion. They receive public credit for strong contributions and constructive feedback when they falter. This signals that it is acceptable to get something wrong and how to fix it.

The reputational dynamics here are powerful but healthy. Reputation motivates effort, but because the setting is small and dialogical, the failure instructs. Students report that they prepare harder for “their” week than for any exam because they don’t want to let their group down. They experience reputation not as a threat but as a spur to excellence where the social pressure acts to pedagogically motivate students to be their best self. This exercise captures the essence of learning-by-teaching: students must organize material, anticipate questions, and explain ideas coherently enough to guide another person’s understanding. The reverse structure also democratizes for students that philosophy is about participating in a shared search for truth.

4. Rock ’Em, Sock ’Em LLMs: The Philosophy Tournament

This is the most elaborate assignment to be used sparingly. Groups of students train and coach a LLM to defend an opposing side of a philosophical issue like whether free will is compatible with determinism or whether euthanasia can be morally justified. Each team gathers sources, crafts prompts, and adjusts training data to train and shape their model to argue better. They then stage a public debate in class between their two models, projected on-screen, followed by a debrief where the rest of the class or students in the tournament analyze the debate and offer praise and feedback.

When students see their carefully trained model spout a contradiction or a cliché, they feel the weight of responsibility that comes with teaching—echoing Duran’s observation that teaching demands reflective self-assessment and repair. It also engages reputational psychology in a productive way for the simple reason that teams want their models to perform well, so they dig deep into the content. Getting a good grade helps too.

5. Write-n-Snap: Analog Thinking in a Digital Age

To counterbalance all this digital immersion, I assign occasional low-tech exercises. Students read a passage from Aristotle or Mill and write their reflections by hand with blue or black ink only. They then photograph and upload the pages. Here the slowness is deliberate by making them write manually engages a different part of their brain. It restores the temporal dimension of thought that benefit when students pause, consider, and rephrase. That pace and visibility makes thought itself tangible again.

By juxtaposing Write-n-Snap with the AI-based assignments, I emphasize that the point in class is to learn, by whatever means works best even if it isn’t the latest technology. Paper books and LLMs can peaceful and productively co-exist. Students see that good thinking can take many forms—dialogue, teaching, debate, or pen-and-paper reflection—and that what matters most is the engagement and the process, not the polish of the product.

Reflections and Thoughts

If there’s a through-line in all these exercises, it is that reputation and learning are entwined. Reputation gives moral and motivational force to our efforts but can paralyze when there is too much concern for our reputations such that it hinders learning. Vonasch’s studies suggest that people guard their reputations with near-mortal zeal because cooperation itself depends on being seen as competent and moral. In the classroom, that same instinct can suppress risk-taking where students would rather avoid controversy than learn something.

These assignments only work because they are framed as a partnership. I tell my students at the outset that if you use AI to replace your mind, you’re training the model. If you use it to extend your mind, you’re training yourself. The point I aim to convey to students–many of whom seem to get it–is that copy and pasting assignments in college will not make one more employable. However, if AI and LLMs make them more productive than their competitors, they can write their own ticket. So, really their purpose shouldn’t be to avoid detection but instead to use AI and LLMs to improve and extend the recognition like math and language, a form of cognitive scaffolding, thereby making them relatively more employable (and better thinkers more importantly) than their thoughtless competitors.

The results have been consistently positive. Participation rates have risen; students attend “reverse office hours” eagerly; their writing shows more reflection and less posturing. The conversations are richer, less rehearsed. Many of my students have discovered that doing philosophy doesn’t mean having the right answers but instead exploring deep, fundamental questions about reality and the human condition.

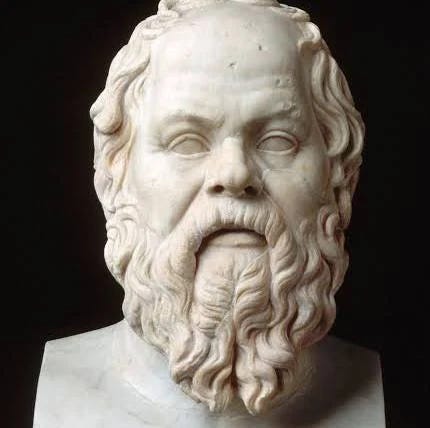

Socrates called himself a midwife of ideas. In my classes, the AI serves as a synthetic midwife that can help professors elicit understanding without replacing the human labor of thought. It lets students fail safely, reflect honestly, and teach boldly. It lowers the reputational cost of inquiry so that curiosity can do its work. When students debate and teach a machine, they take an active role in their development as students and budding philosophers.