I’m the founder of interviewing.io, an anonymous technical recruiting marketplace. In some ways, I’m the meritocracy hipster who was writing about how eng hiring should be meritocratic and about how quotas are bad, way before saying either was cool. At interviewing.io, my team and I have been trying to make hiring meritocratic for the last decade. Briefly, we do anonymous mock interviews. If people perform well in those interviews, they get introduced directly to decision-makers at top-tier companies, regardless of how they look on paper. 40% of the thousands of people we’ve helped were excellent engineers who did not look good on paper and would NOT have gotten in the door through traditional, “meritocratic” channels. Many of those engineers were rejected based on their resumes by the very same companies where they were later hired through us.

Recently, there’s been a lot of pro-meritocracy, anti-DEI rhetoric. The most salient example is Alexandr Wang’s (CEO of Scale AI) tweet about how their hiring process has to be meritocratic (including a catchy new acronym, “MEI”).

— Alexandr Wang (@alexandr_wang) June 13, 2024Today we’ve formalized an important hiring policy at Scale. We hire for MEI: merit, excellence, and intelligence.

This is the email I’ve shared with our @scale_AI team.

———————————————————

MERITOCRACY AT SCALE

In the wake of our fundraise, I’ve been getting a lot of questions…

The post got a resounding “Great!” from Elon Musk a half hour later, followed by a wall of accolades from the Twitterverse. Since then, a “meritocracy board” has sprung up as well.

If you read Wang’s post carefully, you’ll see that he provides no specific examples of how Scale AI makes hiring meritocratic and doesn’t share any details about their current hiring process. I don’t know anyone from the Scale AI team personally, but after doing eng hiring in some form or another for over 15 years, I have questions. Does Scale AI’s hiring process differ substantially from other companies’? Or are they doing the same thing as everyone else: recruiters look at resumes, pick people who have top brands on their resume, and interview them?

If their process is indeed like everyone else’s, no matter what they say, they’re no more meritocratic than the companies who tout DEI hiring practices… and are just virtue signaling on Twitter.

I’ll be the first to admit that DEI is ideologically flawed because of its emphasis on race and gender-based outcomes and its insistence on equality of those outcomes. In the last decade, we’ve seen some pretty bad DEI practices, the most egregious being a company looking up candidate photos on LinkedIn and rejecting qualified white, male candidates. (I talk more about the worst-offending hiring practices I’ve seen over the last decade in the section called The dark side of diversity… and two stories of diversity initiatives gone wrong below. If you just want the juicy bits, read that part.)

However, yelling “Meritocracy!” as if it’s a fait accompli is just as harmful as the worst parts of DEI. In the last decade, we’ve seen countless companies claim to be meritocratic but refuse to talk to candidates unless they had a CS degree from one of a select few schools. There is nothing meritocratic about that. After seeing the pendulum swing back and forth a bunch in this space, I’d even go so far to say that, ironically, the DEI movement has done more for meritocracy than the loud pro-meritocracy movement is doing right now.

I’m delighted that “meritocracy” is no longer a dirty word. But, just saying it isn’t enough. We have to change our hiring practices. We need to stop using meritocracy as a shield to preserve the status quo. If we could instead put into practice the best part of DEI – openness to hiring candidates from non-traditional backgrounds while eliminating the toxic hyperfocus on race and gender and the insistence on equality of outcomes, then we could create a real meritocracy, which is what most reasonable people actually want.1

A quick disclaimer before we go further. To the right, DEI has come to mean mediocrity, and as such, it’s pitted, apples to apples, against meritocracy. That is not the intent here. When I talk about DEI, I’m not talking about the political side of it or how it’s often co-opted by the left as a gateway to Marxism. Similarly, meritocracy has been co-opted by the right to justify racism, eugenics, and god knows what other horrid things. Both extremes are bad. I’m trying to shed all political associations from either word and to just talk about them purely as hiring ideologies.

DEI’s outcomes problem

On its face, increasing diversity sounds great. Some groups are underrepresented in tech, likely because of inequality of opportunity. Talent is distributed uniformly, opportunity is not. Let’s fix it!

Twitter threads like this one (from an engineering leader at Google) are hard to argue with. You should read the whole thing — it’s about a (white) lumberjack’s son who ended up as one of the founding employees at SpaceX.

— Mekka 💉x7 @mekkaokereke@hachyderm.io (@mekkaokerekebye) January 5, 2019Everyone loves SpaceX, and thinks of Elon as the genius founder that invents new types of rockets that are cheaper, faster, more efficient.

It's fun to think of it as SpaceX versus NASA, or Silicon Valley vs Aerospace.

But let's talk about D&I, and logs. Logs as in timber. 🌲

And indeed, ostensibly, DEI is hard to argue against because it speaks to our innate desire for fairness and equal access to opportunity. Many DEI leaders honestly believe this. However, despite the good intentions, in practice, DEI tends to laser focus on race and gender outcomes, and that is hard to argue for.

Over the years, I’ve seen claims that diverse teams perform better, as well as claims that one must have a diverse workforce if one has a diverse customer base. Though it’s often stated as fact, the former is inconclusive — there are studies with clear results for AND clear results against.2 To the best of my knowledge, the latter point is unsubstantiated as well — isn’t the hallmark of a good designer that they be able to design for customers who are different than they are?3

The arguments for diversity are inconclusive, and as such, the ultimate measure of success for diversity isn’t about the performance of an organization or about customer satisfaction. Those are packaged up as obvious side benefits. The way we measure success for diversity is tautological: success is measured by the diversity of our workforce.

What does that mean? In practice, recruiting orgs usually define success by looking at some demographic and its representation in the general population. So, in the case of women in tech, women make up half the U.S. population, so 50% of engineers in an organization should be women. Similarly, 12% of the U.S. population is Black, so for hiring to be equitable, 12% of the engineers in an organization should be Black. Likewise, 19% of the U.S. population is Hispanic, so 19% of engineers should be Hispanic, and so on.

What’s the problem with this approach? It does not account for inputs. The most basic input is: How many female engineers are there in the US? And how many Black or Hispanic engineers are there in the US?

The answer: not enough. Only 20% of CS graduates in the US are women. And there are also not enough engineers of color to get to race parity either. Only 6% of CS graduates in the US are Black, and only 7% are Hispanic.4

Those numbers get even more grim when you pare them down to how companies usually hire: from top-ranked schools. We’ll talk more about this pedigree-based approach to hiring when we discuss the pitfalls of meritocracy. For now, suffice it to say that a few years ago, we ran the numbers to show that getting to gender parity in software engineering is mathematically impossible given companies’ focus on pedigree; though it was unfashionable to admit it, we called out that there really is a pipeline problem.

And then there’s this issue: What portion of those candidates are even applying to your company in the first place? And what portion of those applicants are actually qualified to do the work? The ONLY way to really take race and gender bias off the table is to do blind as much of the hiring process as possible and then to accept that you may not get the numbers you want but that your outcomes will actually be fair.

The dark side of diversity (and two stories of diversity initiatives gone wrong)

In addition to mock interviews, interviewing.io also helps companies source engineering candidates. We know how people perform in mock interviews, and that lets us reliably predict who’ll do well in real interviews. We identify the top performers from practice and introduce them to companies. We’ve been doing it for a while, and our top performers have consistently outperformed candidates from other sources by about 3X.

I promised in the beginning of this post that I’d spill some juicy tidbits. Here goes.

Years ago, we pitched Facebook’s university recruiting team on using us to hire for their intern class. The pitch was that we had thousands of college students from all over the U.S. who had done a bunch of mock interviews, and that we knew who the top performers were. Many of our students did NOT come from the handful of top-tier schools that Meta typically recruited from. If they were to recruit through us, they’d have to do way fewer interviews (we had already taken care of technical vetting), and they’d get a much more diverse slice of the population.

Our only process request was that they conduct interviews with students anonymously, on our platform, so they wouldn’t be biased against top-performing students who didn’t go to top schools.

We didn’t get the gig. The main bit of pushback from Facebook was that anonymity violated guidelines set by the OFCCP. The OFCCP (Office of Federal Contract Compliance Programs) is part of the U.S. Department of Labor and is “responsible for ensuring that employers doing business with the Federal government comply with the laws and regulations requiring nondiscrimination.” One of the many things that the OFCCP requires you to track, if you do business with the federal government, is the race and gender of your applicants. We couldn’t agree to this. While the requirement makes sense on the surface — as they say, you can’t fix what you can’t measure — in this case, it was a Kafkaesque roadblock to achieving the very thing that the OFCCP is fighting for: reducing discrimination.5

More broadly, you can’t take an outcomes-based approach unless your inputs are homogenous and the playing field is level. The biggest advocates of DEI will argue, correctly, that the playing field is not level. Given that it’s not level, focusing exclusively on outcomes creates all manners of perverse incentives — the dark side of diversity is the logical conclusion of an outcomes-based approach: incentivizing the selection of candidates based on race and gender and ultimately discriminating against non-URM candidates.

We’ve worked with companies of all sizes, from seed stage startups to FAANG, and at one point or another, we’ve worked with most FAANGs and FAANG-adjacent companies. We’ve seen it all. In 2022, at the height of diversity fever, one well-known FAANG-adjacent customer approached us with a specific request. Let’s call them AcmeCorp (name obviously changed; they’re a household name, but I don’t want to rake them over the coals publicly because they were a great partner to us until this thing happened).

AcmeCorp’s recruiting team wanted us to do some pre-filtering on the candidates we introduced to them.

We already do some pre-filtering: location, years of experience, visa status, and obviously historical performance in mock interviews. Only the top few percent of our candidates get to talk to employers.

But on our platform, everything is candidate driven. We don’t have a searchable candidate database, and we don’t share candidate data with companies. Rather, we list the companies who hire through us, and our top-performing users can connect with them.

Over our lifetime, plenty of companies have approached us asking if they could get access to just top-performing women and people of color on our platform. It makes sense. Recruiters are given marching orders to find more “diverse” candidates, and this is the result. And it’s a convenient way to pass on liability. Now, instead of their sourcers having to filter out candidates who aren’t “diverse”, we have to do it.

Of course, we’ve always denied these requests. We’re not a “diversity” platform, and we can’t imagine a world where we’d block what jobs and employers our users could see based on their race and gender (information we don’t collect systematically in the first place).6

Even though, on their face, these requests weren’t really OK, we got so many of them that, over time, we got desensitized and would joke internally about how yet another company wanted a binder full of women.

However, AcmeCorp’s request was more egregious than the rest because it gave us visibility into how many companies were behaving internally when faced with diversity goals. It was common knowledge that many companies were doing diversity-specific sourcing, so we weren’t shocked when we were asked to help with that. What wasn’t common knowledge is that companies were blatantly rejecting qualified applicants who didn’t meet their diversity criteria.

AcmeCorp had a fairly complex candidate filtering process in place, and they wanted us to run that same process on any of our top performers who expressed interest in working there.

Here’s how their process worked. Note that AcmeCorp, like many companies, pays differently depending on where you live.

- List a remote job that’s hiring all over the United States.

- When candidates apply from high cost of living areas (e.g., the SF Bay Area, NYC), only consider women and people of color. Reject the rest.

- When candidates apply from lower cost of living areas (e.g., small towns in the Midwest), consider everyone.

In other words, a white man from San Francisco would have no shot at getting an interview at this company — he would be auto-rejected and left to wonder what was wrong with his resume.

Why did this company take this approach? They were willing to pay top dollar for women and people of color but not for other types of engineers, and they hid behind geography to do it. Because of the geographical element, it’s not as blatant as outright rejecting people based on race and gender, but for all intents and purposes, it’s the same.

Outside of this practice being questionably legal at best, it’s also unethical. You can argue that companies should be able to do outreach to any demographic groups that they want. It’s much harder to argue that it’s ok to reject applicants based on their race and gender.

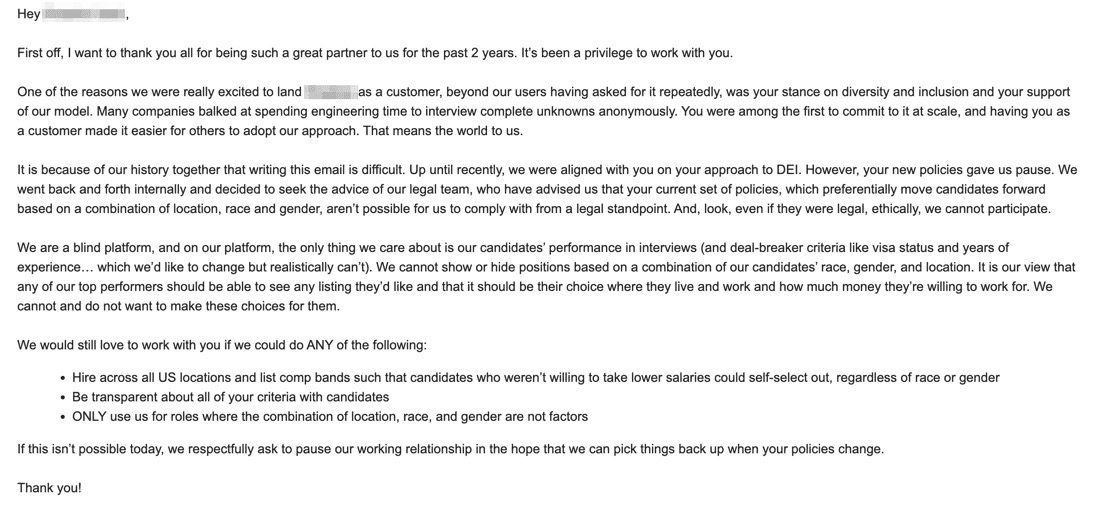

We terminated the relationship.7

Unfortunately, when you tie the success of your recruiting program to gender and race outcomes, these are the behaviors that inevitably arise. For all its flaws, though, the DEI movement, coupled with increasing demand for engineers, propelled companies to make deep changes to their hiring processes. For every DEI horror story, there is an equal and opposing story about a Head of Talent or investor engineering leader who persuaded their eng hiring managers to stop looking just at students from MIT and Stanford, to change their interview processes, to blind resumes, and to do a bunch of other useful things that benefitted every non-traditional candidate.

But, back to what’s happening today. You don’t just get to say “meritocracy” and be done with it. In practice, meritocratic hiring doesn’t really exist, and what companies call meritocracy is anything but.

The false promise of meritocracy

For most sane people, the concept of meritocracy is hard to argue against. Shouldn’t the most qualified person get the job?

Unfortunately, because the definition of “qualified” is murky, meritocracy often becomes a justification for over-indexing on pedigree: where people went to school or where they worked previously. “We just hire the best” often means “we hire people from FAANG, MIT, and Stanford.” Unfortunately, those are proxies for ability, not actual measures of it. Our research has consistently shown that where people go to school isn’t very predictive of what they can do. Where they’ve worked is somewhat predictive, but it’s not the most important thing.8

Despite that, those are the main criteria that companies use when they decide whom to interview, and because that’s the first step in a hiring funnel, it’s the one that gets applied to the most candidates. Any attempts at making the process meritocratic after the resume review (e.g., training interviewers, doing anonymous interviews) are bound to be less impactful because they affect 10X-100X fewer candidates.

Fortunately, for all their flaws, at least technical interviews do focus on ability — once you get in the door, it’s not about how you look on paper but about how you perform. As a result, all other things being equal, how you decide which candidates to let into your process is the litmus test for whether your process is truly meritocratic or not.

Unfortunately, the pedigree-based approach isn’t particularly meritocratic. In our 9 years, we’ve diligently tracked the backgrounds of our candidates, and as I mentioned in the intro to this post, about 40% of our top performers don’t look good on paper (but do as well as or outperform their pedigreed counterparts in interviews).

One of our users got rejected from a top-tier social network company three times… THREE TIMES… based on his resume before he got hired there through us, after doing very well in an anonymous interview. I’ve shared a few diversity horror stories, but the sad reality is that (faux) meritocracy horror stories like this one happen every day. I wish I had a real meritocracy horror story to share, but as far as I know, eng hiring has never been truly meritocratic. If you know otherwise, please do share.

Our data also shows that pedigree has very little bearing on interview performance. Where people went to school has no bearing on their interview performance, and though where people have worked does carry some signal, it’s not nearly as important as other traits — in past research, we’ve found that not having typos/grammatical errors on your resume is a much stronger signal than whether they’ve worked at a top company, as is whether they’ve done a lot of autodidactic work.8

Moreover, in two separate studies completed a decade apart, where recruiters had to judge resumes and try to pick out the strong candidates, we consistently saw that recruiters are only as accurate as a coin flip and largely disagree with each other about what a good candidate looks like.9

That’s why posts like the one from Scale AI get my hackles up. You don’t get to say that you’re meritocratic if you’re just scanning resumes for top brands. That’s not meritocracy. It’s co-opting a hot-button word for clout.

And it’s not just Scale AI. This is how tech companies define being meritocratic and hiring the best. It’s just that not all of them are so self-congratulatory about it.

So how do you ensure that your hiring is actually meritocratic?

How to actually “do” meritocracy, if you mean it

In a recent study, we looked at how recruiters read resumes and how good they are at finding talent. As you saw above, we learned that recruiters are barely better than a coin flip. Another thing we looked at in the same study was what made them pick certain resumes over others.

The two traits that were the most predictive of whether a recruiter would pick you? First, whether you had top brands on your resume, and second, whether you were Black or Hispanic. This is how recruiters work today. If you don’t intervene and make changes, today’s competing approaches will both be implemented by your team simultaneously, resulting in a farcical chimera of fake meritocracy and outcomes-based diversity goals.

So what can you actually do, if you, in good faith, want to run a meritocratic hiring process? (By the way, if you believe that talent is distributed uniformly, by definition, this approach will entail being open to talent from traditionally underrepresented backgrounds.)

First, you have to move away from identity politics and expand the definition of “underrepresented.” You have to believe, in your heart of hearts, that great talent can come from anywhere and must stop focusing arbitrarily on one marginalized group at the expense of another. Basically, you have to be open to any candidate who’s good, regardless of how they look on paper, without prioritizing race and gender. This certainly includes race and gender, but it also includes socioeconomic status, educational background (or lack thereof), and any number of other traits that have nothing to do with someone’s ability to do the job. Hell, why not just stop worrying about candidate backgrounds and have a process that welcomes all and surfaces the best? Following this path will logically require moving away from race and gender outcomes-based goals.

Then, you have to accept and internalize that your current method of deciding who gets to interview, which is very likely focused on brands (where people have worked or where they’ve gone to school), is not only NOT meritocratic but also ineffective. We talked above about how pedigree is very limited in its ability to predict performance.

If you accept both of these premises — expanding the definition of “underrepresented” and moving away from focusing on brands — the hard work begins. Companies have used resumes (and brands by extension) since time immemorial because they’re easy, and as you saw in our data above, they do carry some signal. But even though they carry a little signal, recruiters are not very good at extracting it.

Here’s what you should do to pragmatically and realistically revamp your hiring process to be more meritocratic. I challenge Scale AI and all the leaders on the “meritocracy board” to publicly commit to at least two of these — or to name the specific, actionable approaches they plan to take.

- Change how you read resumes.10

- Give candidates the option of submitting some writing about a past project they’re proud of.

- Give candidates the option of doing a take-home or an asynchronous assessment. Put enough work into those assignments such that you’ll trust their outcome enough to not have to look at a resume.

- [EXTRA CREDIT] Invest what you can in closing the gaps.

Change how you read resumes

First, SLOW DOWN. In the study I mentioned above, we saw that recruiters take a median of 31 seconds to judge a resume, but spending just 15 extra seconds reading a resume could improve your accuracy by 34%.

Our second piece of advice is this. More than 20 years ago, Freada Kapor Klein from Kapor Capital coined the term “distance traveled,” referring to what someone accomplished, in the context of where they started. For instance, Kapor Klein recommends that, in their admissions processes, universities should consider not just the number of AP tests a candidate has passed but the number of AP tests taken divided by the total number offered at their high school. For example, if an applicant took 5 AP tests and their school offered 27, that paints a very different picture from another applicant who also took 5 AP tests when that’s the total number offered at their school. Kapor Capital uses distance traveled as one of their metrics for determining which entrepreneurs to fund. One can easily apply this concept to hiring as well.

The data shows that slowing down is important, and as part of slowing down, when you read a resume, try to evaluate candidates’ achievements, not in a vacuum, but in the context of where they came from. Think about the denominator. But don’t think for a moment that we recommend that you lower the bar — absolutely not. On interviewing.io, we regularly see nontraditional candidates objectively outperforming their FAANG counterparts.

Give candidates the option of submitting some writing about a past project they’re proud of

My friends at KeepSafe and I ran an experiment about a decade ago where we tried replacing resumes with a writing sample about a past project. It was a huge success.

Even today, when we hire at interviewing.io, we use this approach. We mostly hire off of our own platform (we just list our own open positions alongside others). However, not all of our users have done enough mock interviews to have a rating, and for those users, we have a different flow where we ask them to write about a past project. Boy, are the results telling.

Here’s what our application form looks like. Steal it if you want.

Give candidates the option of doing a take-home or an asynchronous assessment

Take-homes and asynchronous assessments are not well-loved by candidates, primarily because of value asymmetry. They ask a lot of the candidate but nothing of the company, and it’s not uncommon for a candidate to have to do hours of work and then never hear anything back.

To be clear, this is NOT the setup we’re advocating. Here’s what we’d advise instead:

Give candidates the option of doing a take-home/assessment that takes no more than 1 hour, instead of submitting their resume. When we say option, we mean that the candidate can decide whether they want to do the take-home or not. If they choose not to, then you’ll read their resume, hopefully using our suggestions above. If they choose to complete the take-home, then you forgo their resume and make your go/no-go decision based entirely on the results of the take-home.

If you choose this route, it’s critical to come up with an assessment whose results you trust. Many companies use a take-home in addition to getting the resume and will still not move forward with candidates who look good on paper. That’s not meritocratic. Take the time you need to come up with a question that’s hard to cheat on and that gets you the signal you need. Yes, coming up with a good assessment takes work. But no one said that making your hiring process meritocratic was easy.

[EXTRA CREDIT] Invest what you can in closing the gaps

This advice probably applies more to big companies than smaller ones, because bigger ones have more resources to effect change. Regardless, if you believe in meritocracy, then you understand that a true meritocracy is not possible without a level playing field for your candidates. One of the best things about the DEI movement is that it’s made us aware how unlevel the playing field really is. Whether you subscribe to DEI or not, this is probably not a controversial statement, and if you want to see true, meritocratic hiring, you have some obligation to help promote equality of opportunity.

Where to begin?

Although I expect that it’s not level in many places, and there are plenty of opportunities to effect change, starting with elementary education11, I'll talk about the inequality I’ve observed firsthand repeatedly over the last decade: the technical interview practice gap. How much you practice is the biggest predictive factor of interview performance — not seniority, not gender, and not a CS degree. And so is socialization. After all, if you’re around people going through the same thing, like at a top-tier CS school, rather than beating yourself up after a disappointing interview, you’ll start to internalize that technical interviewing is flawed and that the outcomes are sometimes unpredictable. Fortunately, there are interventions one can make to close these gaps, and the simplest is to provide practice and community for people who don’t have access to them. Reach out to us about this, find a non-profit that helps people practice, donate to your favorite university if they have a good practice program, or any number of other things.

Ultimately, which gap you choose to help close and how you choose to do it is up to you. But if your company has the means, it’s your responsibility to invest in gap-closing measures. You don’t have to donate money. You can offer mock interviews to your candidates before their real interviews. You can start an apprenticeship program. You can encourage your engineers to do some tutoring. However you approach it, though, you can’t talk about meritocracy with a straight face and not do something to level the playing field.

Footnotes:

-

In fairness, the Scale AI post positioned them as symbiotic. I believe that as well. ↩

-

There are many sources arguing for and against diversity leading to better-performing teams. Here are some examples:

For: https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/diversity-and-inclusion/diversity-wins-how-inclusion-matters

Against: https://medium.com/the-liberators/in-depth-the-double-edged-sword-of-diversity-in-teams-765ff72a55da (except for “age diversity”) and https://corpgov.law.harvard.edu/2021/05/25/diversity-and-performance-in-entrepreneurial-teams/ ↩ -

One of the most insulting examples of the “we need a diverse workforce to serve our diverse customer base” argument occurred when I was pitching Amazon on using interviewing.io to hire. This was years ago, and back then, out of curiosity, I’d always ask the organizations we were pitching why they valued diversity. I don’t think I ever got a good answer, but this one was especially bad. One of the recruiters we met with went on a long diatribe about how Amazon sells lots of shoes and you need women on the eng team because women understand shoes better than men. ↩

-

Getting more women and people of color to study computer science is a worthy cause. Hell, getting anyone who’s historically been marginalized to study computer science is worthwhile. It’s great for our economy, and it’s currently one of the best levers for upward social mobility available. But, while we hope more companies do these things, it is not reasonable to expect that companies can be responsible for educational interventions that often need to start at the elementary school level. Of course, companies should do what they can. But expecting them to pull off mathematical impossibilities is irrational, and the DEI movement’s stalwart refusal to acknowledge the pipeline problem undermines the movement as a whole. ↩

-

I was actually able to get in touch with a former OFCCP higher-up who admitted that rejecting anonymity in hiring was against the spirit of OFCCP requirements. But they sadly wouldn’t go on the record. ↩

-

The closest we’ve ever come to doing this is our Fellowship program, where we gave free practice to engineers from traditionally underrepresented backgrounds. It was a great program, but what made it great was that our interviewers were eager to help these candidates. We were able to do free practice because our interviewers graciously agreed not to charge. That said, if I were to run this program again, I’d probably focus more on socioeconomic status and non-traditional credentials rather than just race and gender. ↩

-

Here’s the email we ended the relationship with. I’m including it because it was hard to write and even harder to hit send on, but I think we did the right thing, and maybe someone else will need to write something like this in the future… in which case, please steal our copy.

↩

↩ -

Research that shows that having attended a top school isn’t very predictive and that, while experience at a top company is somewhat predictive, it’s not the most important thing:

↩ ↩2 -

Anyone who’s read my writing for a long time will pause here and wonder why I’m OK with resumes and recommending anything about reading them. Until recently, I was stalwartly against resumes and convinced that they carried no signal whatsoever. Then, as part of the recruiter study I mentioned, we built some simple ML models to judge resumes and compared their performance to human recruiters. They all outperformed recruiters, and that surprising result made me reverse my stance. ↩

-

First study (2014): https://interviewing.io/blog/resumes-suck-heres-the-data

Second study (2024): https://interviewing.io/blog/are-recruiters-better-than-a-coin-flip-at-judging-resumes ↩ -

There are other gaps that start way before someone gets to college. Enumerating the is out of scope of this piece, but this writeup by the National Math and Science Initiative is a good place to start. ↩