Today’s Congress is facing a technology modernization challenge that will determine how independent it remains as branch of government - versus becoming captured by private tech companies. If Congress falls behind, its ability to legislate independently, assert its constitutional prerogatives, and maintain the separation of powers is at risk.

During my time on Capitol Hill, the atmosphere often reminded me of the startup accelerators I’d worked in. Highly ambitious, mission-driven staffers worked with the same intensity I saw in tech founders. Similar ambition, with the staffers seeking political options instead of stock options. Suits replace hoodies, but the drive and optimism are the same.

The technology pitch from large tech companies to startups is familiar: Amazon, Microsoft, and Google all offer free cloud credits, and the promise of quick, frictionless scaling. Startups eagerly sign on, until the bills start rolling in and switching vendors means weeks of costly rearchitecture and testing. Vendor lock-in is not a theoretical risk - it’s a real threat to the integrity of how Congress functions.

Modernizing Congressional technology and data infrastructure is urgently needed, but Congress risks falling into the same traps as both tech startups and executive branch agencies: dependency on outside vendors, regulatory capture, and taxpayer dollars wasted with no discernible public benefit. Ironically, while some members of Congress seek to regulate Big Tech, they simultaneously risk becoming operationally dependent on the very companies it aims to oversee.

The solution lies in the collaborative spirit that built America itself. Open source software operates on the same principles as American democracy: transparency, shared responsibility, and continuous improvement. Just like our founding fathers showed that government works best when all citizens can participate, open source development shows that technology works best when everyone can contribute, review, and improve it.

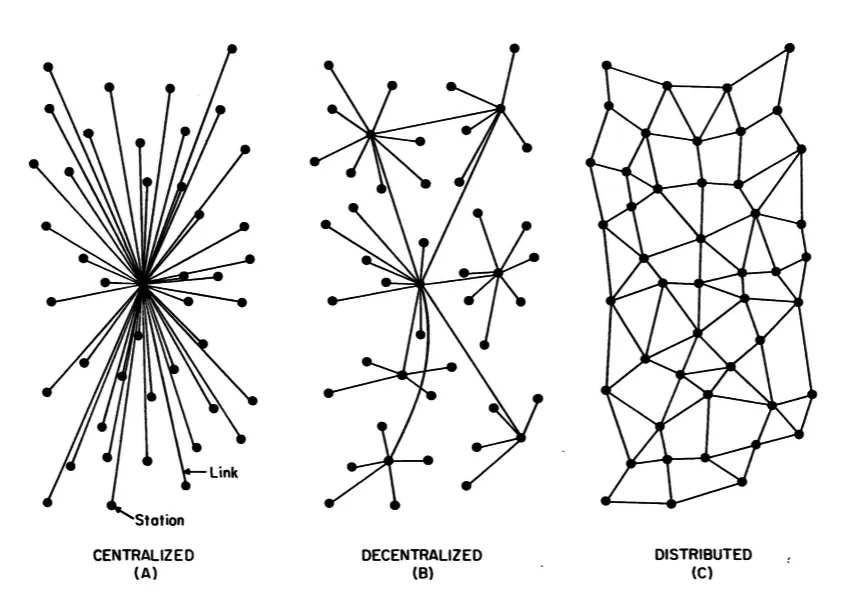

Unlike the executive branch (where the Clinger-Cohen Act and FITARA force centralized Chief Information Officers (CIOs),) Congress operates by distributed governance. IT responsibility is spread between the House Chief Administrative Officer (CAO), Senate Sergeant at Arms (SAA), committees, and individual offices. The Committee on House Administration and Senate Rules and Administration provide policy direction, but each of the 541 offices (435 House, 100 Senate, plus others) manages its own technology choices and budget.

This decentralized architecture is an expression of America’s constitutional design. Article I, Section 1 vests legislative powers solely in Congress, ensuring separation from the President and Supreme Court. The result: hundreds of small, nimble teams able to experiment, fail quickly, and adapt - creating “laboratories of democracy,” as Justice Louis Brandeis put it.

Congress’s distributed, autonomous offices reflect cutting-edge software architecture - microservices - where each component operates independently, exchanging data only when needed. One congressional office can upgrade its constituent management system without disrupting anyone else. Similarly, zero-trust security assumes threats inside and outside the walls, with each office maintaining separate protocols and requiring explicit authentication. This micro-segmentation ensures that breaches don’t cascade through the entire institution.

The legislative branch’s very structure provides the opportunity for the resilience and flexibility lacking in centralized executive branch IT systems. Congress’s smaller scale and distributed culture mean individual offices can experiment with new tools without risking catastrophic system-wide failures. Hundreds of these “microservices” could allow innovation and security improvements to be deployed incrementally. This stands in vivid contrast to the status quo of executive agencies' massive, centralized bureaucracies.

The open source movement is a symbol of the core American values of transparency, collaboration, and democratic participation - encapsulated in a demonstrably successful software development methodology. This has been recognized in the Federal Source Code Policy, established in 2016, which requires executive agencies to release at least 20% of new custom-developed code as open source, recognizing the public benefit of transparency. Congress has already begun embracing these principles through initiatives like the Congress.gov API, and other enhanced data structures that make legislative information more accessible to researchers, civil society organizations, and citizens. The Congressional Data Task Force has modernized the legislative data exchange, improving public access through better APIs and data formats. These efforts represent the foundation of what could become a comprehensive transformation toward open, collaborative governance.

Congress should embrace open source principles not merely as a technology strategy, but as an expression of its Constitutional role. The collaborative, transparent, and iterative nature of open source development aligns perfectly with the decentralized nature of the First Branch. Several key principles should guide congressional open source adoption.

First, transparency builds accountability. When legislative tools and processes are publicly auditable, citizens can better understand and engage with their government.

Second, collaboration enhances quality. Perspectives and contributions from new entrants improve outcomes, as Eric S. Raymond's "Linus's Law" demonstrates.

Third, modularity reduces risk. Distributed systems with interoperable components are more resilient than monolithic structures.

The legislative branch's smaller scale and distributed culture make it an ideal testing ground for open source government innovation. Unlike executive agencies with massive, complex bureaucracies, individual congressional offices can experiment with new tools and approaches without risking catastrophic system-wide failures.

The risks of vendor lock-in and regulatory capture are real, but they are not insurmountable. Congress can learn the right lessons from the experiences of the executive branch, build its internal expertise, and maintain vigilance against the influence of powerful special interests. The path forward requires sustained commitment, adequate resources, and most importantly, the wisdom to recognize that in democracy, the means are just as important as the ends. Congress must modernize its approach to technology before it can modernize the technology itself, and ensure that digital transformation strengthens, not undermines, the constitutional principles it was created to serve. And in an era when public trust in institutions remains fragile, the stakes of getting this transformation right couldn’t be higher.

Programs like TechCongress and the Horizon Institute for Public Service are changing this dynamic. They place tech experts directly in congressional offices, slowly building the foundation for bigger changes. TechCongress has placed over 100 fellows with members of Congress since 2015, working with notable figures like Speaker Nancy Pelosi, Senators Tim Scott, Elizabeth Warren, and Tom Cotton.

The choices that the Senate Sergeant-at-Arms and House Chief Administrative Officer make today about technology infrastructure, vendor relationships, and governance frameworks will determine whether Congress emerges from this transformation as a more capable and responsive institution - or one that continues to compromise its independence, and effectiveness, and its Constitutional prerogatives.