Last month I concluded a three-year term as an associate editor at Security Studies, an international relations journal. I began in early 2023, the dawn of the LLM era, but ended right in the middle of it.

One thing that changed in that relatively brief time is the sheer volume of manuscripts. The editor-in-chief emailed us last summer to warn that submissions were double or triple our typical averages. Many had little to do with the journal’s topic and instead focused on computer science or internet security. It seems people were using AI to generate terrible manuscripts and then shotgun-spraying them across the academy with little regard for quality or fit.

As a result, our desk reject rate rose to 75%. A desk reject is the first filter for academic journals, where the editor-in-chief determines which manuscripts should go out for peer review. Here, it served as an effective slop filter because the slop was easily recognizable. Our workload still increased, but only slightly.

But what happens when competent political scientists can use LLMs to generate publishable manuscripts? Ones that pass not just the editor’s desk but peer review?

The political scientist Andy Hall wrote recently:

Claude Code and its ilk are coming for the study of politics like a freight train. A single academic is going to be able to write thousands of empirical papers (especially survey experiments or LLM experiments) per year …We’ll need to find new ways of organizing and disseminating political science research in the very near future for this deluge.

“Thousands” seems optimistic unless one adopts a wholly monastic lifestyle, but hundreds is very plausible. And these papers won’t be bad. They’ll be narrowly useful, methodologically sound, and for the most part not very interesting.

The next day, Hall posted proof-of-concept, producing a paper written almost entirely with Claude Code:

[T]oday I had Claude Code fully replicate and extend an old paper of mine estimating the effect of universal vote-by-mail on turnout and election outcome...essentially in one shot. …The whole thing took about an hour. This is an insane paradigm shift in how empirical work is done. [emphasis added]

I looked at the AI-created paper, and while I’m not qualified to judge its methodological rigor, it looks like the typical quant paper I might find in a peer-reviewed journal. I would never read it, but someone interested in the subject might.

What do we do with this?

The first thing is probably to stop calling it “slop”. As Max Read notes, slop “suggests a set of qualities—forgettability, predictability, unoriginality, lifelessness—rather than a particular origin.” The coming AI-generated papers may be unoriginal but they aren’t lifeless in that way. They’re technically proficient. They follow the form. They’re adequate. They’re easy to do and require little creativity, but also constitute the kind of legitimate incremental work that Thomas Kuhn called “normal science”.

Call it Slop-Plus? Premium Slop? Maybe that’s too harsh. The German term for Kuhn’s normal science is Normalwissenschaft, so maybe Automatenwissenschaft?

Whatever we call it, what does its emergence mean for academia?

I suspect the value of original or elegant theory will become more important. Good quant work is becoming cheap and plentiful; good theory remains hard. Perhaps ethnographic work will become more valuable, and original data collection that AI still cannot do.

But the biggest effect is that peer review now becomes more about discernment or taste. If anyone can produce a competent empirical paper on any topic, the bottleneck moves to identifying which questions are important to ask in the first place. This was already part of my job as an editor: given two reviews, which are sometimes contradictory and occasionally baffling, how can I apply my own judgment and sense of the field to decide if the paper should move forward.1

In that world, the question for reviewers and editors is less “is this right?” and more “why does this matter?” This is inescapably subjective but not completely so, since it requires a solid grounding in ongoing debates. It still demands knowing the tensions and productive gaps, the interesting puzzles and the seemingly settled conventional wisdom.

This concept actually has a name: phronesis. That was Aristotle’s term for practical wisdom, or the capacity to discern the right course of action in particular circumstances. Unlike episteme (scientific knowledge) or techne (technical skill), phronesis cannot be reduced to rules or algorithms. It requires experience, judgment, and what Aristotle called “perception”. That means not simply intelligence but the intellectual ability to see the salient features of a specific situation.

Michael Polanyi made a similar distinction with “tacit knowledge”. We know more than we can tell. A master craftsman cannot fully articulate why one piece of work is excellent and another merely competent. The knowledge is embodied, contextual, and resistant to formalization. This is exactly what makes it hard to automate, at least for now.

Will this remain a human quality? Maybe I’m being anthropocentric. AI systems are trained on human judgments, after all. But they still learn a kind of averaged, derivative taste. As a result they can recognize what has been valued but I suspect will struggle to anticipate what should be valued. The long-term question is whether taste is fundamentally about some deep-level pattern recognition (eminently automatable) or about something else: context, stakes, the je ne sais quoi of academic research.

Isaiah Berlin called this quality “a sense of reality” in political judgment: the ability to perceive what is possible and what matters in a given historical moment. It’s not clear LLMs have that sense.

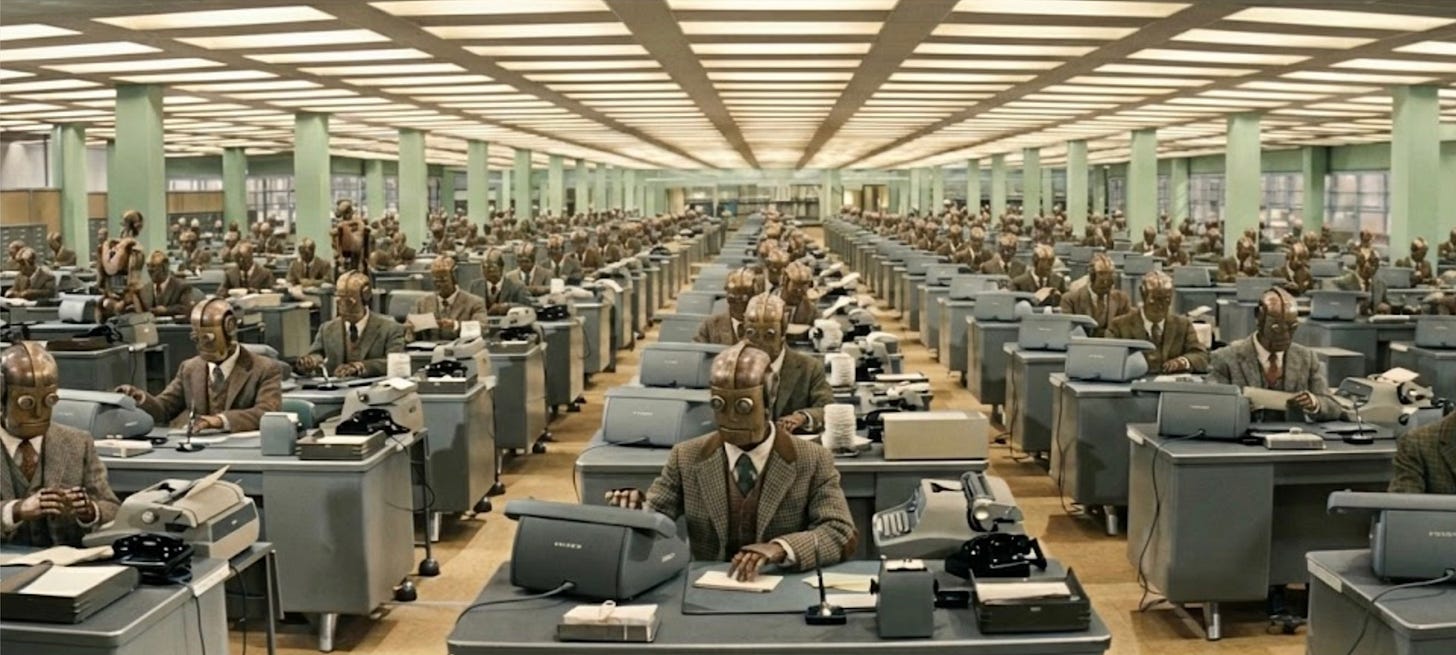

That’s not to say LLMs are only marginally useful for social science. They will likely prove genuinely important for replication, and especially pre-publication replication, which is crucial work that’s also unrewarding and tedious enough that few bother. If AI can routinely re-run analyses and flag discrepancies, that’s already a big contribution to scientific integrity. I’ve also found them helpful for summarizing short texts and, my most frequent and frivolous use, for producing images for my lectures (like the one at the top of this piece). So I’m not an AI Luddite so much as someone for whom the technology is not yet transformative.

Publish and Vanish

If discernment becomes the ultimate arbiter of quality, we are heading even more toward a two-tier system in academic publishing. Top journals will focus on papers that are strikingly original or make important theoretical or empirical breakthroughs, while everyone else will publish the AI-produced papers that incrementally advance our understanding of narrow things. And perhaps theory will gain increasing prestige over sophisticated methods of analyzing data. One can dream.

Both theory and empirics are of course key parts of science, but the danger is the flood of Automatenwissenschaft becomes a kind of scholarly dark matter that exists to pad CVs and satisfy bureaucratic metrics, but which no one actually reads or relies upon. This is already true to some extent, but AI greatly accelerates the process.

For many scholars this moves them from a “Publish or Perish” model to a “Publish and Vanish” one. And when consuming the literature, the bifurcation forces scholars to rely even more on prestige hierarchies as a heuristic for importance. Paradoxically, the leveling effect of AI might make academia more elitist.

Professors have been at the forefront of slop consumption. We were swimming in AI essays before most people knew what ChatGPT was. It’s still all my colleagues complain about. We saw how annoyingly effective it was, so it’s not surprising that we would turn to the same tools for our research, especially for coding or quantitative work. The technology that flooded us with student essays will now flood us with our own work, and we will need more of the same discernment we’ve been complaining our students lack.

(For previous posts on the topic, see also “Facts Will not Save You: AI, history, and Soviet sci-fi” and “Teaching in the Age of AI: how I avoided a shitty semester”.)