“The FDA’s traditional paradigm of medical device regulation was not designed for adaptive artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies.” — the FDA

After 21,000+ hours of training and over a thousand major operations, I recently completed chief residency and finally became a board-eligible general surgeon. In the final two years of my training, nearly every elective abdominal or thoracic operation was performed using Intuitive Surgical’s da Vinci xi surgical robot.

Many surgeons routinely record and archive operative video to allow for “game tape” review: identifying inefficiencies, optimizing technique, and analyzing technical errors when complications occur. Until recently, this data was local, living on the hospital’s servers or the surgeon’s own hardware.

Earlier this year, Intuitive Surgical released the da Vinci 5 across the US and European markets:

The da Vinci 5 comes with two major changes from the previous model:

The Intuitive Hub now automatically uploads all that “game tape” video to Intuitive’s cloud servers after a period of local storage. This was marketed to hospitals as a way to offload data management burden while enabling quality analytics.

The system now provides haptic feedback, from the robot’s arm to the surgeon console. This also enables the device to capture haptic inputs, precisely recording exactly what manual instructions the surgeon is inputting at any given time.

It doesn’t take a crystal ball to imagine where the industry is hoping this leads: intra-operative video and haptic inputs are the exact training data an AI model would need to learn how to autonomously perform surgery.

Ask any robotic surgeon, and they’ll tell you we’re 5-10 years away from the moment when these systems stop just assisting and start deciding.

Sitting back from the console, watching this four-armed machine tower over my patient, I kept returning to one question:

Who is ensuring this technology is safe for when that moment comes?

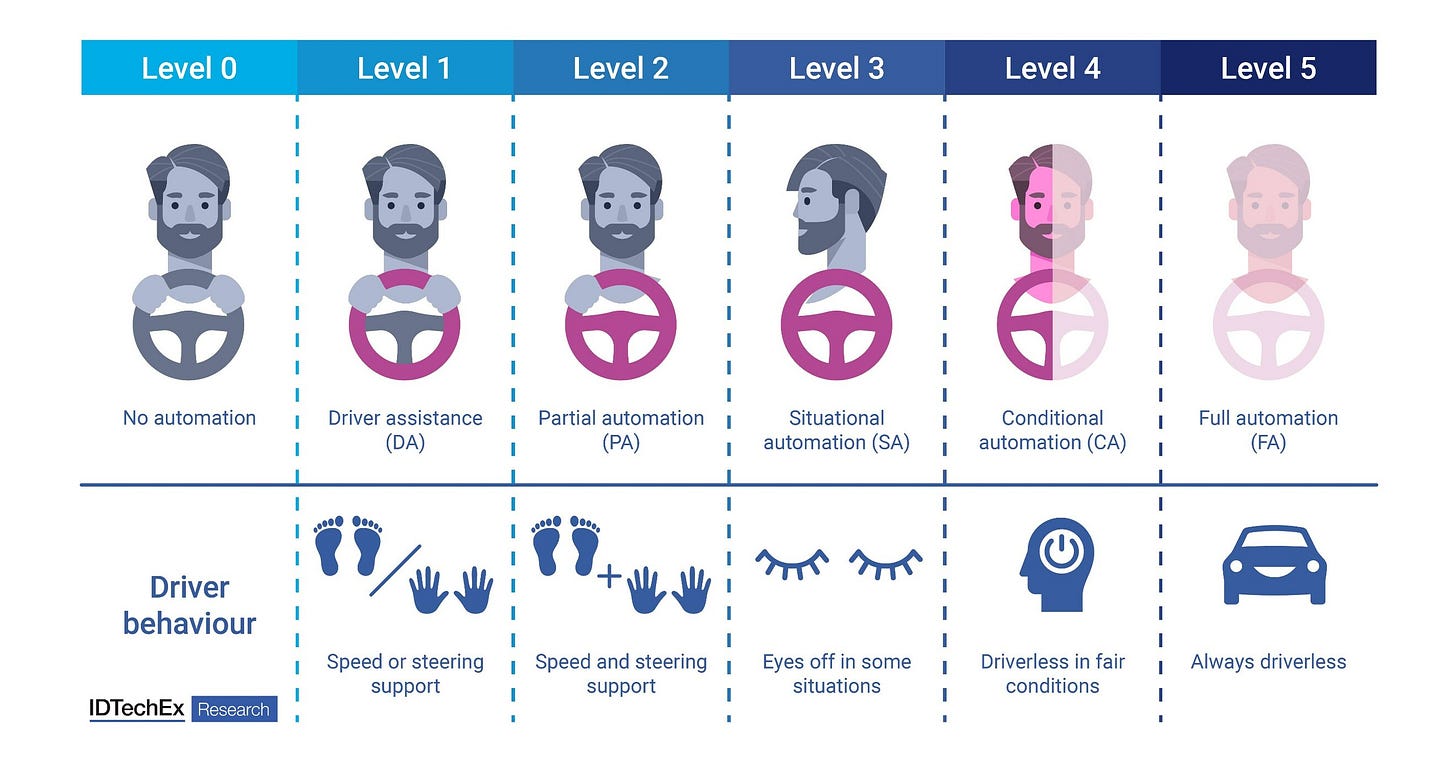

Let’s first establish some common terms. The language of “levels of autonomy” is borrowed from autonomous vehicles (AVs):

Adaptive Cruise Control is considered Level 1 autonomy, while Tesla’s Full Self Driving is considered Level 2. Waymo’s cars, where the user sits in the backseat and is not responsible for monitoring the car, is considered Level 4.

Consider, then, that three of the 49 surgical robots the FDA has already cleared have demonstrated Level 3 autonomy — capable of executing certain surgical tasks independently under specific conditions.

Right now, the tasks that are being executed autonomously are relatively minor; the three Level 3 automations already on the market are a bone milling machine, an automatic prostate biopsy machine, and a hair transplant machine:

The manufacturer of this follicular unit extraction machine has explicitly re-branded as an “AI-first company”, even going so far as to change their TLD to “Venus.ai”.

The next step — Level 4-5 autonomy — will be equivalent to the surgeon “sitting in the backseat” while the robot “drives”. At this level of autonomy, with the surgeon “in the backseat”, these surgical robots will be — for all intents and purposes — “practicing medicine”. Yet the FDA — who is exclusively responsible for regulating medical devices in the United States — explicitly doesn’t regulate medical practice. The FDA continues to refer to this entire class of technology as “robotically-assisted surgical devices,” implying no autonomous decision-making capabilities and creating a jurisdictional void. Who is responsible when one of the already-deployed Level 3 systems malfunctions during autonomous operation? The surgeon? The hospital? The manufacturer? The robot itself?

These malfunctions are not a theoretical risk. Over ten thousand adverse events related to surgical robotic systems were reported to the FDA between 2000 and 2013, in an era when all surgical robots were still at Level 1; device and instrument malfunctions, such as the falling of burnt/broken pieces of instruments into the patient (14.7%), electrical arcing of instruments (10.5%), unintended operation of instruments (8.6%), system errors (5%), and video/imaging problems (2.6%), constituted a majority of the reports. Furthermore, the rate at which these events are being reported has increased 32-fold since 2006, dramatically outpacing the 10-fold increase in robotic surgery volume over the same period.

A consumer may reasonably assume that in order to get a device cleared by the FDA, its manufacturer would need to produce an indisputable body of clinical testing data. In reality, only 39% of these systems included clinical testing data in their FDA submissions. While the submissions for all three Level 3 robots did include such data, some ML capabilities went entirely undisclosed:

2 of the surgical robots were reported to have machine learning-enabled software features in their submissions to the FDA. However, 3 additional surgical robots were marketed to have machine learning-enabled capabilities on their product websites that were not in their FDA summary documents.

In a way, this could have been expected: RAND has proven adequate test-drive validation for AVs would require billions of miles of driving data. How could a manufacturer possibly produce adequate clinical testing data for an autonomous surgical robot? Cadavers and simulation can only get you so far, as any medical student will attest. AVs can be tested in computer simulations, on closed courses, and even on public roads with backup drivers. Would you volunteer to be a “test track” for an autonomous surgical robot?

The honest answer right now is: nobody. Not comprehensively, anyway.

The FDA is still regulating these systems as “devices” while they’re rapidly evolving into medical practitioners, which will place them explicitly out of the FDA’s scope. And manufacturers — eager to capture their share of a market estimated to be worth between $9.3 and $38.4 billion within the next ten years — are moving faster than regulators can track, while sometimes developing and marketing AI capabilities that are never even disclosed to the FDA.

“Autonomous AI/ML applications that can cause serious injury or harms (i.e., morbidity or mortality) to patients if they malfunction would be considered high risk…The burden of responsibility may shift toward the stakeholders involved in AI/ML development and deployment.” — the FDA

If we start now, we can still build the regulatory framework we need.

Over the next several posts in this series, I’ll explore what we can learn from autonomous vehicle regulation, who needs to be at the table to build a better regulatory landscape, and what a multi-stakeholder consortium for proactive regulation could look like before Level 4-5 systems reach operating rooms.