The fastest remote-controlled airplane flight ever recorded took place in 2018, with a top speed of 545 miles/hour. That’s 877 km/h, or Mach 0.77!

What was the limiting factor, preventing the pilot-and-designer Spencer Lisenby’s plane from going any faster? The airstream over parts of the wing hitting the sound barrier, and the resulting mini sonic booms wreaking havoc on the aerodynamics. What kind of supercharged jet motor can propel a model plane faster than its wings can carry it? Absolutely none; the fastest RC planes are, surprisingly, gliders.

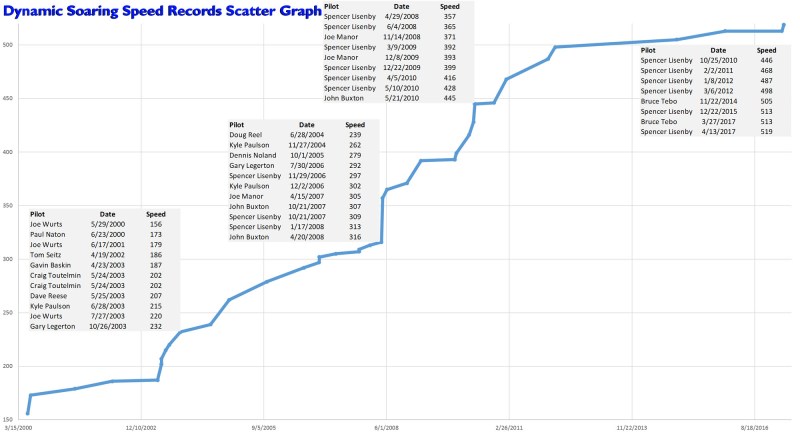

Dynamic soaring (DS) was first harnessed to propel model planes sometime in the mid 1990s. Since then, an informal international competition among pilots has pushed the state of the art further and further, and in just 20 years the top measured speed has more than tripled. But dynamic soaring is anything but new. Indeed, it’s been possible ever since there has been wind and slopes on the earth. Albatrosses, the long-distance champs of the animal kingdom, have been “DSing” forever, and we’ve known about it for a century.

DS is the highest-tech frontier in model flight, and is full of interesting physical phenomena and engineering challenges. Until now, the planes have all been piloted remotely by people, but reaching new high speeds might require the fast reaction times of onboard silicon, in addition to a new generation of aircraft designs. The “free” speed boost that gliders can get from dynamic soaring could extend the range of unmanned aerial vehicles, when the conditions are right. In short, DS is at a turning point, and things are just about to get very interesting. It’s time you got to know dynamic soaring.

The Physics of DS

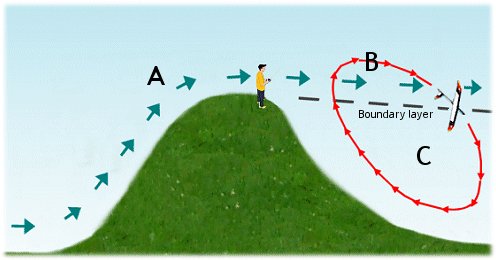

When wind blows over a hill, it has to go up and over, with emphasis on the “up”. Glider pilots have used this ridge lift to their advantage for a long time, and the model airplane practice of gliding around indefinitely in the ridge lift on the front side of a hill is called “slope soaring”. With an infinite source of lift, model gliders can do all sorts of fun acrobatics using very little power, as long as they don’t hit the hill or fly up and over to the back side of the mountain.

On the back side, the air pulls back down again, and there’s a strange turbulent zone between the moving air up-top, and the wind-shadow in the valley where the air is still. The back side was known to eat model airplanes, first pulling them downwards a little, then tumbling them around, and then leaving them to slowly sink in the still air. If you’re lucky, it’s a long walk down to pick up your intact plane. If you’re unlucky, you can collect your pieces off the leeward side of the hill.

On the back side, the air pulls back down again, and there’s a strange turbulent zone between the moving air up-top, and the wind-shadow in the valley where the air is still. The back side was known to eat model airplanes, first pulling them downwards a little, then tumbling them around, and then leaving them to slowly sink in the still air. If you’re lucky, it’s a long walk down to pick up your intact plane. If you’re unlucky, you can collect your pieces off the leeward side of the hill.

Until one day, when glider pilot extraordinaire (and aeronautical engineer) Joe Wurts flew up and over. He realized that he couldn’t make it back against the strong wind, and didn’t want to hike down, so he aimed the plane at the valley floor. It picked up speed, crossed the turbulent zone, and entered the still air where he was able to fly it back to the crest of the hill because he wasn’t fighting the strong headwind. When it climbed and re-entered the wind stream, he noticed that it had picked up speed. Then he started doing it on purpose.

And thus was born Dynamic Soaring with RC gliders. (Ta-daa!) It seems like a perpetual motion machine at first, but the trick is that every time the plane re-enters the fast-moving air, it gets pushed downwind. Diving down into the still air lets it fly back to where it started without receiving the equivalent push in the opposite direction. As long as the plane gets more of a push than it loses to drag during the return leg of the flight, it comes out of the circle with more energy — it’s going faster.

Insanely Fast Model Airplanes

And fast is fast. The progress in speed records stalled for a number of years due to the fact that there were no commercially available radar guns that would measure above 300 mph — supercars are slow compared to carbon-fiber RC gliders. When better radar detectors became available, largely due to continual pestering by Spencer and the DS community, measured speeds jumped up dramatically — that’s the vertical line in the middle of the graph.

When the sport was young, the highest achievable speeds were limited by the stiffness of the wings: Flutter is the wing-killer. If an oscillation in the wing starts up at high speed, there’s a lot of energy to keep it amplifying, and the result is that the wing tears itself apart or away from the body of the plane.

When the sport was young, the highest achievable speeds were limited by the stiffness of the wings: Flutter is the wing-killer. If an oscillation in the wing starts up at high speed, there’s a lot of energy to keep it amplifying, and the result is that the wing tears itself apart or away from the body of the plane.

Modern planes have flutter-resistant airfoil designs, but are also made out of carbon fiber and other high-tech composites. Unlike “normal” gliders, DS gliders have the enviable problem of being confronted with too much wind energy, so they can be built strong without worrying so much about weight.

Today, the limits to top speed are aerodynamics and the human pilot. The air moving over the top of the wing has to cross the sound barrier, where it is no longer compressible. This creates shock waves in the middle of the wing, which kill its aerodynamic efficiency. The solution, as with full-scale planes, is to sweep the wings backwards. This smoothes out the pressure gradient along the wing, but it means an entire re-design of the plane. This is where Spencer’s next design will be going.

For a great rundown of the state of the art in dynamic soaring, you should really check out Spencer’s talk. If you just care about the planes, the history of his own designs starts around 20 minutes in.

When Spencer manages to design and build a plane that can approach the sound barrier, the next limiting factor may be the human in the loop. At speeds already in excess of 200 m/s, a human’s reaction and decision time of around 250 ms to 500 ms translates to 100 m of plane travel. If a plane hits bad turbulence at those speeds while only 20 m above the ground, it could be carbon-fiber dust before any meatbag even has a chance to blink. To quote Spencer, “With each new speed, you get this feeling like you’re in over your head and your brain can’t keep up with what’s happening.”

While we’re not quite there yet, it’s likely that the fastest DS plane in another 20 years will be significantly more automated because humans just won’t be able to keep up. This brings a slew of new challenges, from instrumentation and motors to algorithm design. There are tons of autopilot systems available out there in the broader model airplane hobby, like Ardupilot for instance, but none of them have the closed-loop response times that will be necessary for transonic DS. But they’re faster than people.

The Albatross, the Drone, and the Windmill

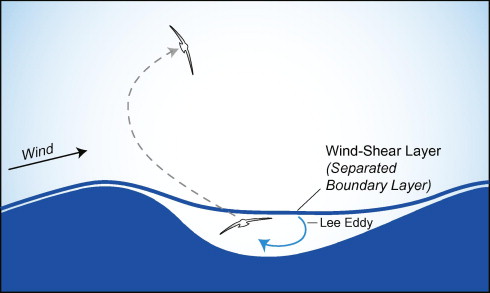

Lord Rayleigh first noticed that albatrosses flew for long distances without flapping their wings. He called this “gust soaring”. But perversely, it wasn’t until after the DS revolution in model airplanes that we fully started to understand the aerodynamics fully, and we’ve still got a lot to learn from nature on this front.

Lord Rayleigh first noticed that albatrosses flew for long distances without flapping their wings. He called this “gust soaring”. But perversely, it wasn’t until after the DS revolution in model airplanes that we fully started to understand the aerodynamics fully, and we’ve still got a lot to learn from nature on this front.

An albatross has an array of strain and windspeed sensors along the length of its wings that enable real-time analysis and control of its flight that we can’t even begin to approach. They’re reported to be able to soar in the wake of the waves even while they’re asleep, a wingtip skimming only a few centimeters over the surface of the water.

Perhaps one future application of dynamic soaring will be UAVs that save power by harvesting windspeed gradients, whether on the ocean or taking advantage of specific terrain. We’d love to hear silent DS-bots replace their noisy helicopter-based brothers. Imagine gliders that pause along their course when they approach the leeward side of a windy hill, loop around to build up speed, and then move along to the next. Combine this with thermal lift sources over the flats, or solar, and you might have something.

But before our heads get too lost in the clouds, let’s return to physics. You might be thinking “hey, with all this free energy out there, why aren’t we harvesting it already?” The “dynamic” part of dynamic soaring comes from the top turn: the plane only gains energy when it is in the fast-moving air. The bottom half of the loop is just getting back to where it started. If you didn’t need to go anywhere, you might imagine skipping the inefficient return path and doubling the energy-harvesting efficiency simply by tethering the plane to the ground with a tall mast. Let the wing spin a generator, maybe use three of them, and you’ve invented the modern windmill, which is at least twice as efficient as the best DS plane out there.

So maybe the future of dynamic soaring is exactly like the present: a fun sport that’s chock-full of adrenaline, aerodynamics, and no shortage of design challenges. Or maybe the future for you is to discover DSing at all. In another world from the high cost of competitive carbon planes, you can get started for nearly nothing with a DIY foam model or just cheese out and buy one. Beginner models are surprisingly robust, and if you wreck it, you can glue it back together or harvest the servo motors and start again. Happy soaring!