- Published on

- Authors

- Name

- Taras Sereda

- Name

- Natalie Serrino

- Name

- Zain Asgar

Speeding up PyTorch inference on Apple devices with AI-generated Metal kernels

tl;dr: Our lab investigated whether frontier models can write optimized GPU kernels for Apple devices to speed up inference. We found that they can: mean measured performance of our AI-generated Metal kernels were 1.24x faster across KernelBench v0.1 problems, and 1.87x faster across KernelBench v0 problems.

Why use AI to generate kernels for Apple devices?

AI models execute on hardware via GPU kernels that define each operation. The efficiency of those kernels determines how fast models run (in training and inference). Kernel optimizations like FlashAttention1 show dramatic speedups over baseline, underscoring the need for performant kernels.

While PyTorch and tools like torch.compile2 handle some kernel optimizations, the last mile of performance still depends on handtuned kernels. These kernels are difficult to write, requiring significant time and expertise. It gets especially challenging when writing kernels outside of CUDA: expertise in non-CUDA platforms is rarer, and there is less tooling and documentation available

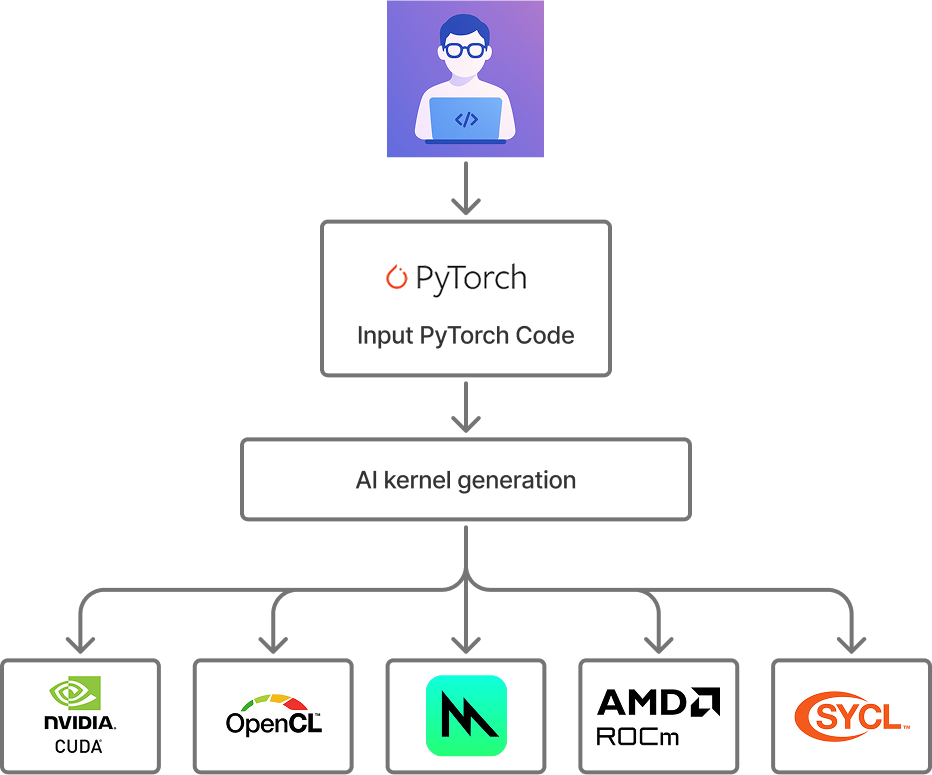

We set out to answer a simple question: could frontier models implement kernel optimizations automatically, across different backends? Billions of Apple devices rely on Metal kernels that are often under-optimized, so we started with Metal.

Our vision: Autonomous kernel optimization for any target platform using frontier models.

Across 215 PyTorch modules, our results show the generated kernels ran 87% faster on Apple hardware compared to baseline PyTorch. This approach requires no expertise in kernel engineering and can be done nearly instantly.

Here's a preview of what we discovered:

- Cases where models surfaced algorithmically unnecessary work and removed it (that PyTorch didn't catch)

- The impact of incorporating performance profiling and CUDA reference code

- Why a simple agentic swarm dominates over individual frontier models

Update for KernelBench v0.1

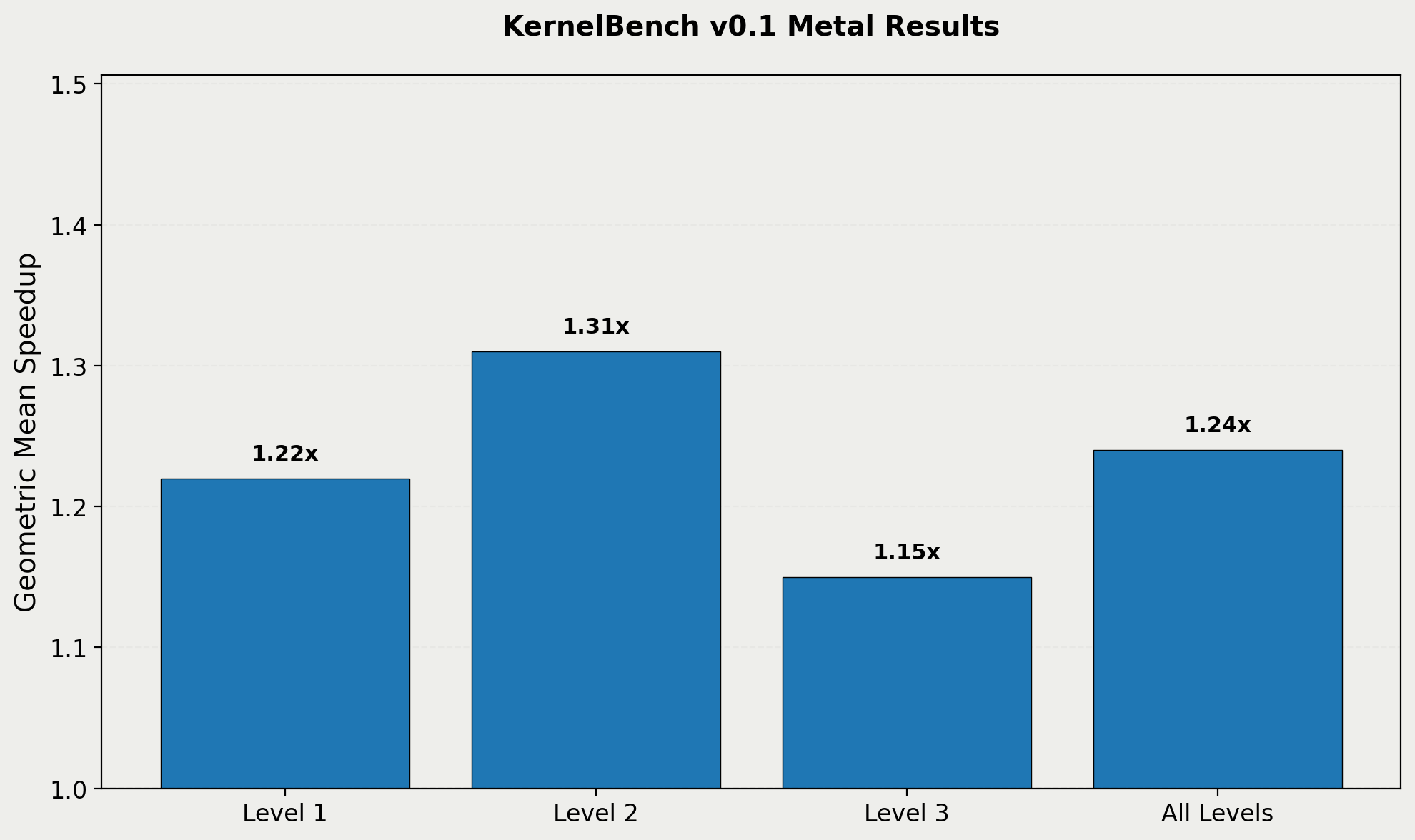

The first version of this blog focused on results for KernelBench v0, which was an earlier version of the benchmark. We have since run the experiments on KernelBench v0.1, which makes a number of improvements, such as larger shape sizes.

Performance results on KernelBench v0.1 benchmark.

We found that our approach produces a speedup of 1.22X on KernelBench v0.1, as opposed to the 1.87X on the KernelBench v0. For posterity, we are keeping the original results available, but the KernelBench v0.1 numbers are the most accurate and up to date for this work.

Methodology

We included 8 frontier models from Anthropic, DeepSeek, and OpenAI in our analysis:

- Anthropic family

- claude-sonnet-4 (2025-05-14)

- claude-opus-4 (2025-05-14)

- OpenAI family

- gpt-4o (2024-11-20)

- gpt-4.1 (2025-04-14)

- gpt-5 (2025-08-07)

- o3 (2025-04-16)

- DeepSeek family

- deepseek-v3 (2025-03-25)

- deepseek-r1 (2025-05-28)

In terms of test inputs, we used the PyTorch modules defined in the KernelBench3 dataset. KernelBench contains 250 PyTorch modules defining ML workloads of varying complexity. 31 modules contain operations that are currently unsupported in the PyTorch backend for MPS (Metal Performance Shaders), so they were excluded from this analysis. (We ended up excluding 4 additional modules for reasons that will be discussed later.)

| KernelBench Category | Description | # of Test Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Level 1 | Simple primitive operations (e.g. matrix multiplication, convolution) | 91 |

| Level 2 | Sequences of multiple operations from Level 1 | 74 |

| Level 3 | Complete model architectures (e.g. AlexNet, VGG) | 50 |

When evaluating the agent-generated kernels, we need to assess both correctness and performance relative to the baseline PyTorch implementation (at the time of writing, torch.compile support for Metal is still underway, so it could not serve as a comparison point. MLX is also a great framework for Apple devices, but this work focused on pure PyTorch code optimization, whereas MLX is its own framework). We also made sure to carefully clear the cache between runs, otherwise cached results can falsely present as speedups.

| Experimental Variable | Specification |

|---|---|

| Hardware | Mac Studio (Apple M4 Max chip) |

| Models | Claude Opus 4, Claude Sonnet, DeepSeek r1, DeepSeek v3, GPT-4.1, GPT-4o, GPT-5, o3 |

| Dataset | KernelBench |

| Baseline Implementation | PyTorch eager mode |

| Number of shots | 5 |

First approach: A simple, kernel-writing agent for Metal

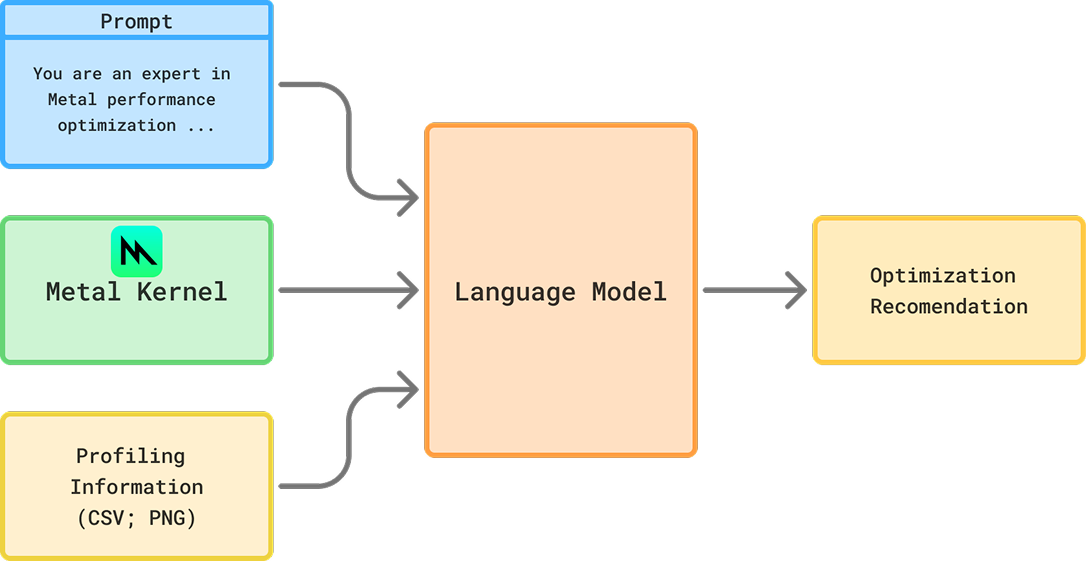

We begin with the simplest implementation of the kernel-writing agent for Metal:

- Receives the prompt and PyTorch code

- Generates Metal kernels

- Assesses if they match the baseline PyTorch for correctness4.

- If they fail to compile or are not correct, an error message is passed back to the agent for another try, with up to 5 tries permitted.

It's interesting to see how the correctness increases with the number of attempts. o3, for example, gets a working implementation about 60% of the time on the first try, and reaches 94% working implementations by attempt 5.

o3's success rate by generation attempt and kernel level. We limited the agent to 5 tries, which seems sufficient for Level 1 and 2 kernels, but Level 3 kernels may benefit from further shots.

Let's look at each of our 8 models correctness rates, broken down by whether or not the implementation was faster than our baseline or not:

Kernel correctness, broken down by whether or not the optimized version was faster than the baseline.

The reasoning models are pretty good at generating correct kernels across levels, although the non-reasoning models are also capable of doing this sometimes. However, other than GPT-5, these models are more often generating implementations that are slower than the baseline PyTorch. GPT-5's success at generating faster implementations for Level 2 problems is particularly notable.

How did the generated kernels do?

Every agent produced some kernels that were faster than baseline, and some of them came up with pretty cool stuff. GPT-5 produced a 4.65X speedup for a Mamba 25 state space model, primarily by fusing kernels to reduce the overhead of kernel launch and improve memory access patterns.

Mamba2 Example

Some of the optimizations were surprisingly clever. In one case, o3 improved latency by over 9000X! o3 assessed the code and identified that given the model's configuration, the results would always be 0s, mathematically. This was not a trivial realization, but it did make the implementation itself trivial.

There were 4 problems, all from Level 2, where the most optimal implementation showed that the problem could be reduced to a trivial solution. Despite the true cleverness shown by the models, we excluded these from our analysis - but in the real use cases with imperfect code, this type of speedup mechanism would be quite useful.

Trivial Example

One interesting thing to note is that the AI-generated kernels don't actually have to be faster every single time to be useful. For long running workloads, it makes sense to profile different implementations - this could even happen automatically. So as long as the AI-generated implementation is sometimes faster, it's valuable - we can always fall back to the baseline implementation when the AI-generated implementation doesn't work or is slower.

Let's evaluate the average speedup compared to the baseline for each of our 8 agents. Based on our realization above, the minimum speedup is always 1X - this is the case where the generated implementation either doesn't work or is slower than the baseline. We use the geometric mean here rather than the arithmetic mean6.

Average speedup by model, broken down by level.

We can see that using GPT-5 produces an average speedup of ~20%, with the other models trailing. One possible conclusion: we should use GPT-5 for kernel generation, possibly giving it some additional context. This would make sense if all of the models tended to behave the same way - generally finding the same optimizations on a consistent set of problems, and failing to optimize other problems.

This isn't what the data actually shows though! Breaking it down by which model did the best across problems, we see that GPT-5 does the best, at 34% of problems where it generates the best solution. But there are another 30% of problems where another model generated a better solution than GPT-5!

Across problem levels, this chart shows which model performed the best (or baseline if none of the models beat the baseline performance).

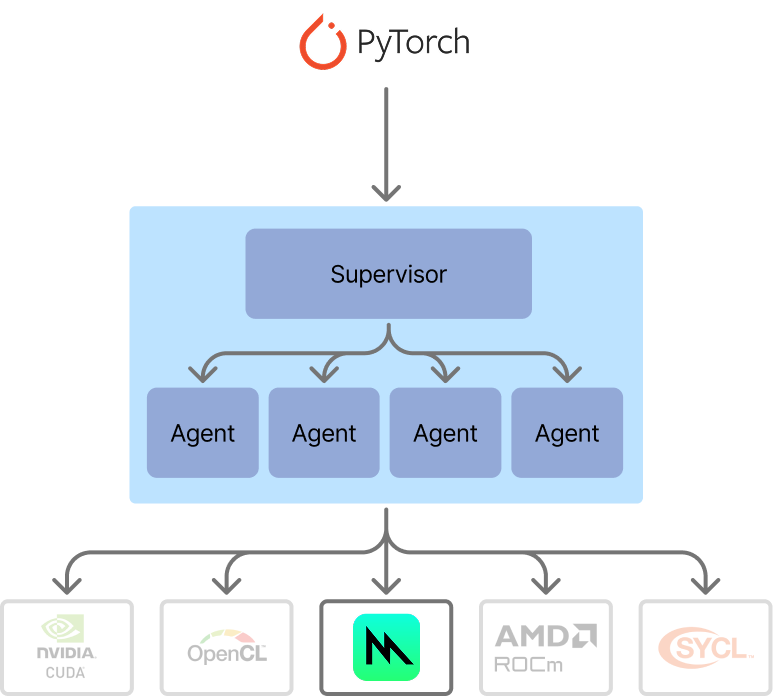

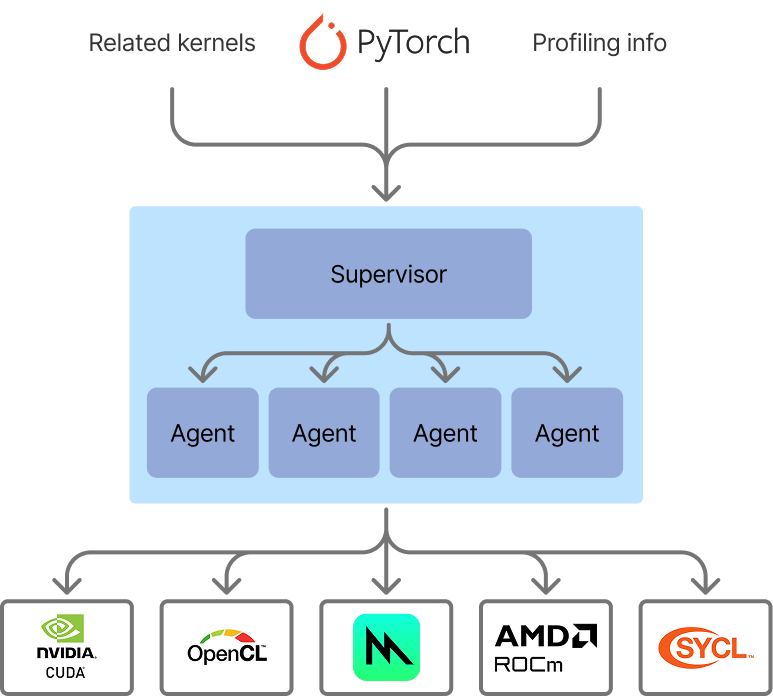

An agentic swarm for kernel generation

This leads to a key insight: kernel generation should use a "Best of N" strategy. Extra generation passes are relatively cheap, it's human effort and the runtime of the model (once deployed) that are expensive.

Our flow for optimized kernel generation now looks like an agentic swarm. We have a supervisor, which is simple for now. It assesses the generated kernels across all agents, times them against the baseline, and then selects the optimal implementation for the problem. The ability to time and verify implementations against a baseline makes kernel generation a really good candidate for AI generation - it's much more convenient than some other code generation use cases, because we need minimal supervision to evaluate results on the fly.

The architecture of our agentic swarm for kernel generation. In this iteration, the supervisor is simple, but in upcoming work we will extend the supervisor to be more dynamic.

Let's see how our agentic swarm performs compared to the standalone models' performance from earlier.

Performance of the initial agentic swarm implementation for kernel generation, showing significantly improved results compared to standalone agents.

We can see this approach gives us better results than even GPT-5 - an average 31% speedup across all levels, 42% speedup in Level 2 problems. The agentic swarm is doing a pretty good job already with minimal context - just the input problem and prompt. Next, we tried giving more context to the agents in order to get even faster kernels.

Adding more context to improve performance

What information would a human kernel engineer need to improve the performance of their hand-written kernels? Two key sources come to mind: another optimized reference implementation, and profiling information.

As a result, we gave our agents the power to take in two additional sources of information when generating kernels for Metal:

- A CUDA implementation for those kernels (since optimized CUDA references are often available due to the pervasiveness of Nvidia GPUs)

- Profiling information from gputrace on the M4.

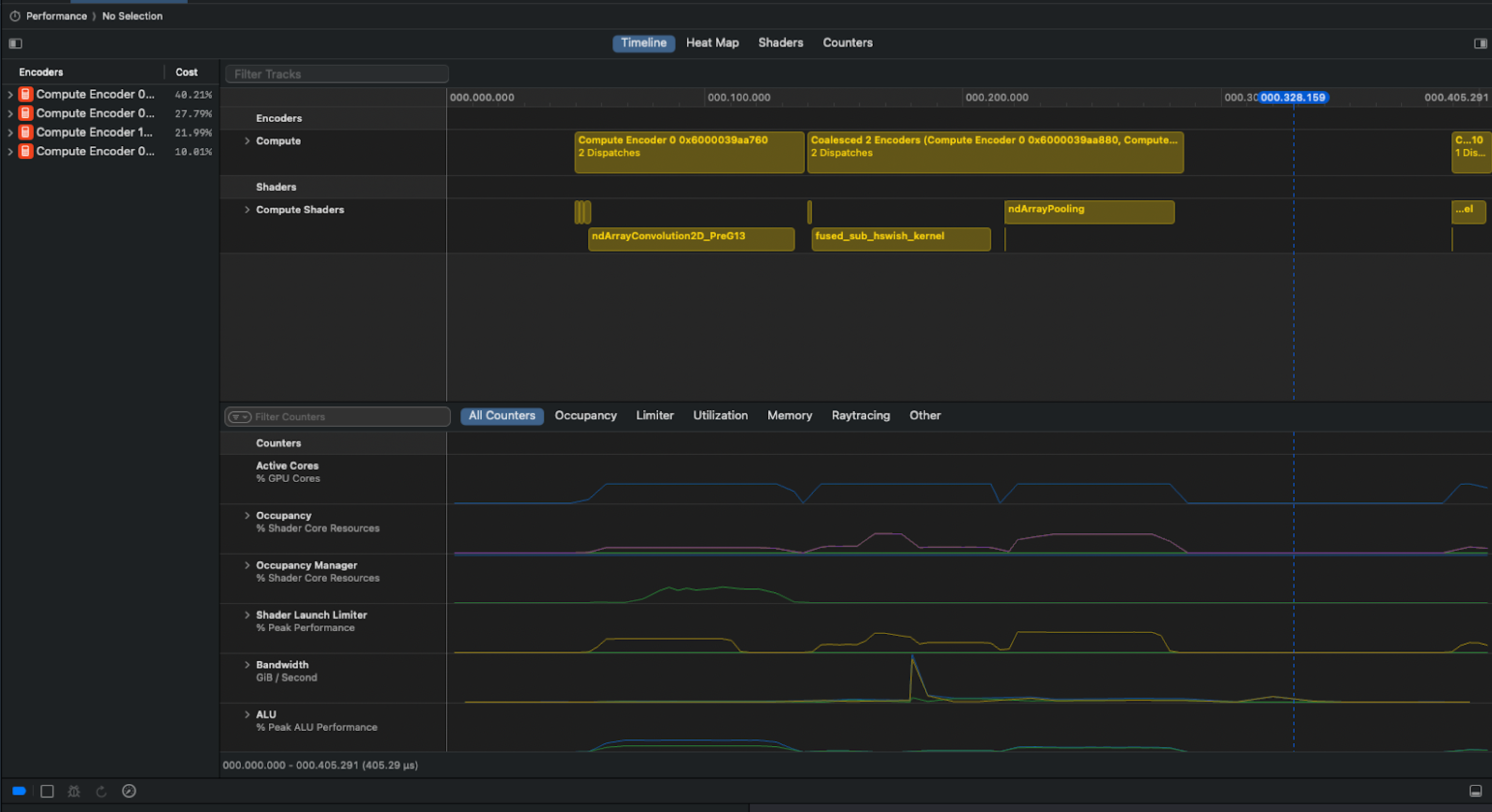

Unfortunately, Apple does not make the Metal kernel profiling information easy to pull programmatically via Xcode… So we had to get creative.

We solved the problem by using Bluem's cliclick tool to interact with Xcode's GUI. Our Apple Script capture summary, memory and timeline views for each collected gputrace:

Example screenshot from Xcode used for analysis. You can see in the screenshot above that there is a clear pipeline bubble after the ndArrayPooling, resulting in idle time.

We could only add profiling information to models that support multimodal inputs. We divided out the screenshot processing into a subagent, whose job it was to provide performance optimization hints to the main model. The main agent took an initial pass at implementation, which was then profiled and timed. Screenshots were then passed to the subagent to generate performance hints. The maximum number of shots remained the same as before - 5 shots total.

Subagent architecture

Similar to our previous finding that the best model varied depending on the problem, we also saw that there was no "single best" configuration in terms of context. Sometimes, adding just one piece of information - either the CUDA reference code or the profiling information - produced the best result. Other times, adding both was helpful. There were still cases where the pure agents with no additional context performed better than the agents with more context!

Best agent context configuration by problem level. We can see that the baseline PyTorch is now only superior to the best generated kernels in about ~8% of cases.

The results are particularly striking for Level 2 kernels. Our assessment is that this is because Level 2 kernels benefit more from fusion than Level 1 kernels. Level 3, on the other hand, may be too complex to generate in a single pass. Stay tuned for some improvements where we break down the problem into more manageable chunks for the agent to handle.

That being said, there were still some good kernels for Level 3. DeepSeek-R1 improved on the default implementation with advanced fusion techniques for a VisionAttention problem. It also showed awareness of Metal-specific features, leveraging threadgroups for more efficient shared memory. While there are still further optimization opportunities left on the table, this implementation was over 18X faster than the baseline PyTorch!

VisionAttention Example

Now, let's evaluate the performance of our agentic swarm. Previously, we did Best of N analysis across all frontier models. Now we do Best of N analysis across the different configurations of each frontier model (CUDA only, CUDA plus profiling, etc). Remember that generating multiple candidate implementations and testing them for performance is a lot "cheaper" than human experts manually writing the code, or running less optimized models at high volume - so offloading more generation to the swarm is worthwhile if it delivers noticeably better results.

The overall performance of the full agentic swarm at kernel generation for Metal on the problems tested.

This is a great speedup - 1.87x better on average than the baseline, nearly instantly, directly from pure PyTorch code. The vanilla agents only saw a 1.31x average speedup, so adding in this additional context almost tripled the improvement we saw!

Looking at the distribution of improvements, we see that the median speedup was about 1.35X. Some kernels measured 10-100X speedup, although we expect those are likely inflated from noise from measuring small kernels. If we exclude 10X and above speedups, the geometric mean speedup is 1.5X. (As mentioned before, all analyses exclude the 4 "trivial" kernels, which were thousands of times ffaster by cutting out unnecessary work.)

The distribution of measured speedups for the agentic swarm (215 problems total, 4 trivial kernels with large speedups excluded). Median speedup was 1.35X, (geometric) mean 1.87X. If we exclude 10X speedups and above, geometric mean speeup is 1.5X.

Wrapping up

These results show that it's possible to automatically drive significant improvements to model performance by automating the kernel optimization without any user code changes, new frameworks, or porting.

AI can take on portions of optimization that a human kernel engineer would do, leaving the human effort focused on the most complex optimizations.

We can automatically speed up kernels across any target platform using this technique.

Soon, developers can get immediate boosts to their model performance via AI-generated kernels, without low-level expertise or needing to leave pure PyTorch:

- Dynamically speeding up training workloads as they run

- Automatic porting new models to new frameworks/devices (not just Metal)

- Speeding up large scale inference workloads

We are hard at work at pushing the envelope further with this technique - smarter agent swarms, better context, more collaboration between agents, and more backends (ROCm, CUDA, SYCL, etc). We're also working on speeding up training workloads, not just inference.

With this technique, new models can be significantly faster on every platform on day 0. If you're excited about this direction, we'd love to hear from you: hello@gimletlabs.ai.

Note: This post was updated 11/20/2025.

Footnotes

Tri Dao, Daniel Fu, Stefano Ermon, Atri Rudra, and Christopher Ré. FlashAttention: Fast and Memory-Efficient Exact Attention with IO-Awareness. NeurIPS 2022. ↩

Jason Ansel, Shunting Jain, Amir Bakhtiari, et al. PyTorch 2: Faster Machine Learning Through Dynamic Python Bytecode Transformation and Graph Compilation. ASPLOS 2024. ↩

Anne Ouyang, Simon Guo, Simran Arora, Alex L. Zhang, William Hu, Christopher Ré, and Azalia Mirhoseini. KernelBench: Can LLMs Write Efficient GPU Kernels? ICML 2025. ↩

We tested the generated kernel's output against the default implementation's output on 100 random inputs. We set a 0.01 tolerance for both relative and absolute. Let

abe the generated kernel output, andbbe the reference kernel output. Outputs were considered equal if for every element in the output,absolute(a - b) ≤ (atol + rtol * absolute(b))held true. ↩Tri Dao & Albert Gu, Transformers are SSMs: Generalized Models and Efficient Algorithms Through Structured State Space Duality. (ICML 2024) ↩

When averaging speedup ratios, the arithmetic mean will be falsely optimistic. Consider the case where you speed up a task by 2X, and then slow it down by 2X. This would be speedups of

2.0and0.5. The arithmetic mean would naively say you saw a speedup of(2+0.5)/2 = 1.25, even though you stayed the same speed. The geometric mean would correctly say the speedup was1.0(no speedup). ↩