It's worth discussing how all this works so you understand the challenges that are being overcome here. The ability to run multiple DOS programs at once is a pretty neat trick, given that this software heralds from an era of computing that was just barely ahead of what the Apple ][ was doing in 1978. If you want to skip this, go ahead.

The root of the problem is that the IBM PCs basic architecture crystallized a very long time ago, in 1981. In a world where ten kilobytes of RAM counted for about what a gig does now, there was not a lot of room for "overhead" and the idea that you would run two programs simultaneously was generally unrealistic except at the high end of the computing world, which most PC buyers were nowhere near. You needed every bit (ha) of memory you could get, and when memory became more affordable a few years later, it was too late to change anything.

After just a couple years on the market, MS-DOS had become the

unquestioned OS of choice for the PC*

and developed a monumental stable of software, every bit of which

was essential to someone, somewhere, and could not be easily replaced. Thus

began one of the longest tails in technology history, as the PC industry and

Microsoft began contorting themselves to try not to

break compatibility with old software while still moving forward with advanced

functionality.

*(specifically, since there were MS-DOSes for

other architectures, and other OSes for the PC)

Because DOS was developed under constraints very similar to those in the late '70s that gave us the "bitty boxes" (C64, Apple ][, ZX Spectrum, etc.) it was not built with any kind of "supervision" in mind. In other words, there was no abstraction level above the current running program. DOS was more like a set of tools than what we think of as an operating system now - specifically, it had no "process management"; no concept of "processes" at all, in fact.

When the machine booted, the part of DOS that was considered "the OS" - the code for accessing disk drives, writing text to screen, etc. - was copied into memory, and then execution was handed off to the command interpreter, COMMAND.COM, which was an application like any other, at which point you could begin entering commands to use the computer.

At this point, DOS was no longer "running" in any meaningful way. The code was "resident," meaning it was present in the computer's memory, but the processor wasn't executing any of it. Instead, the CPU was busy executing whatever the current program was - if you were at the command prompt, then all the code the PC was executing was part of COMMAND.COM. When you launched another application, COMMAND.COM was vacated and replaced by that other application.

In other words, while an application was running, DOS was almost totally out of the picture. The only time execution returned to DOS itself was when the application requested a "service" from DOS, like accessing a disk drive, at which point it would tell the CPU to go execute one of DOS' stored routines for this, and when that routine was done, control would return to the application. This meant that, generally speaking, the current program had absolute control of the PCs execution and it's memory. It could in fact choose to overwrite DOS itself, obliterating it out of memory, and DOS couldn't do a damn thing about it.

The currently running app also had the option to speak directly to hardware. The whole purpose of DOS was to abstract things like that so programs wouldn't need to know the details of the system they were running on, but since the IBM PC was extremely consistent hardware-wise in its early incarnations, it was entirely optional for developers to take advantage of that, and often there were reasons - of performance, perhaps - to bypass DOS and do things directly.

DOS provided disk access routines, but the app could blow right by them and shoot commands straight to the floppy drive if it wanted. DOS provided routines for printing text and clearing the screen, but the app could just write directly to video memory. I can't speak to how common this kind of behavior actually was, but it certainly wasn't rare, and it speaks to a larger problem - DOS apps simply expect total control over the system.

If you run two DOS apps at once, they're going to stomp on each other, because each one thinks it's in charge of the whole machine. The first one would store data in the same spot that the second one stored program code, and thus one would overwrite the other and crash it. So DOS was a single-tasking operating system - you could run one program at a time, and when you wanted to run another, you had to exit, return to the command prompt, and then launch your other app.

Consequently, if you were working on something in Microsoft Multiplan and wanted to go look up some data in dBase, you had to quit completely out of Multiplan and then start dBase, which would take over the system and totally overwrite the previous app. To get back to where you were you'd have to exit dBase, restart Multiplan, load your document and find your place again - in the process, totally forgetting what you were there to do in the first place, because it's so many steps and takes so long.

Right from the get-go, PC users wanted to be able to look at one program, then rapidly switch to another. On its face this seems to mean "run two programs at once," which is what we do now, but that's not quite the full story. Let's touch on how that works nowadays, however.

Multiprocessing

To be clear, you cannot run two programs "at once" on a computer. Some would call this semantics, but it's important in a very real way, especially when talking about 80s-era PCs.

Modern multicore CPUs get very close to true parallel processing by letting separate programs run on separate cores, but of course, nobody has a CPU so big that they have one core per process. And even if you did, programs still have to share other resources - the system bus, hard drives, and so on. Access to these resources has to be carefully managed so that only one application can use them at a time, and each one has to be cleaned up after before another one can use the same resources. Otherwise, one program could leave the hardware in a state where the commands that the next program sends put it in an unusable state and crash the machine, or corrupt data.

Even with all our modern pipelined cleverness, you have the fundamental problem that a CPU, and a computer in general, has a limited amount of physical hardware and can't dedicate some to each individual program that's running. When you have more processes running than you have silicon, the only option left is to share resources by dividing up the amount of time that each process gets to use the hardware - this is one of the oldest concepts in computing, and goes back to the late '50s.

The fundamentals of this process are simple: At any given moment, one program has near-total control of the entire system, to execute its code and use all the resources, and then after it executes for a bit, it goes into a paused state and control is handed off to the next program, which does its work and then hands off to the next. This continues in a round-robin fashion, so that every program gets to use the hardware for a certain portion of every second.

Modern implementations take this to a fever pitch with all the complex machinations used to make this process efficient, but the fundamentals have never changed; this is how your PC is operating right now.

One big hurdle to overcome in implementing this is that programs don't just execute instructions in a vacuum. As code is executed, there are side effects. Some are values internal to the CPU, like the status of CPU registers and the current position of the instruction pointer. This is called "CPU state," and is specific to each running program. When you switch from one program to another, you have to save that information - called "context switching" - and restore it when you come back. Storing this info takes extra time and memory.

Another hurdle is the state of other hardware. If two programs are talking to the hard drive, you can't let them both just blindly issue commands every time they get control of the CPU. The first process might start a data read that the second process interrupts with a data write, confusing the hard drive controller. So when switching from one process to another, you also have to save the state of these other hardware resources - and possibly even delay switching tasks until those hardware requests are complete.

If you have enough RAM to store this state, and if your apps don't need too many cycles per second to appear responsive, you can do all this and the user will feel like they're "running multiple programs at once."

Now, in business applications - the driving force behind the first couple decades of computing - actual "multiprocessing" of this type is not as important as simple usability - users just don't want to have to close one program in order to open another, as they did throughout the DOS days. That, ultimately, is the goal: it doesn't matter if the computer is perfectly speedy, or if programs can run simultaneously, it just matters that users not have to lose all their work in one program simply in order to look at another.

Multitasking

This desire was of course tremendous right from the start of computing. Who wants to be stuck in one program at a time? So, almost from the earliest days of the IBM PC, software was created to enable task switching with various degrees of success.

Early Attempts

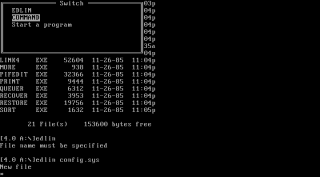

Microsoft actually released a version of DOS with true multitasking support, but it generally required software to be specially written for it. You can see it here - EDLIN is running, and I can switch to a new command prompt by pressing Alt and selecting from a menu, or I can start a new task.

This didn't solve the core problem - that you wanted to run your old, 1983-vintage copy of dBase II, and your old copy of Multiplan, at the same time. Since neither of those programs were developed for this version of DOS, they couldn't play ball. This creates a chicken and egg problem wherein nothing was written for multitasking DOS, so nobody would buy multitasking DOS, and since nobody had that DOS, nothing would be written for it.

Even if software did get updated for new OSes, users had already spent a lot of money on the software they had by the time anyone started trying to solve this problem, and they wouldn't have wanted to re-buy that software. The feature that users needed was to share the machine between two apps of any vintage, with both apps thinking they were the only program running on the machine.

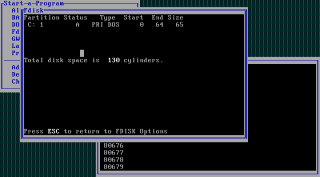

An IBM product, TopView, was another early attempt to fully solve this problem. It was a textmode program, not a graphical one, but it allowed multiple DOS apps to run at once, with their text output diverted into separate "windows" on a shared "desktop." Here you can see it running fdisk and GWBASIC simultaneously, with both executing at once - while I'm doing things in fdisk, the code in GWBASIC continues incrementing a number. So this is true multiprocessing, after a fashion.

TopView only worked if the apps were "well behaved." This is a term you'll see throughout articles on this topic, and what it means is that the app didn't do any direct hardware access - it used DOS "system calls" for everything, which gave TopView an opportunity to "intercept" those calls and redirect them for its own purposes.

For instance, when a program wrote to what it thought was character position 2,10 on the screen, TopView altered the coordinates so they drew into the "window" it had created for that app instead. The advantage to this is that you can simply hand off the processor to each app one at a time and allow them to do what they want, and the results will always end up safely back in TopView's hands where it can figure out where they're meant to go.

The biggest problem is that this stops working the moment your app touches direct video memory, for instance, which many did, making them incompatible with this approach. Also, TopView just sucked. I used it for about 20 minutes while writing this article and every step of the process was unpleasant. Being limited to textmode does nothing to help the situation.

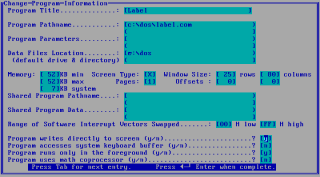

Footnote: The third pic is the TopView PIF Editor for later reference. PIFs tell Topview how to run apps - this will be explained much more thoroughly later in this article, since TopView evolved, in a sense, into Windows itself.

Task Switchers

There was a specific class of commercial products called "task switchers" that allowed you to run multiple programs and switch between them with a shortcut like alt+tab, and in fact early versions of Windows, as you'll see, were often little more than this. These programs couldn't run simultaneously - at any given moment, one program had complete control of the screen and all hardware resources, and then when you switched tasks, that program got completely suspended and another one took over.

There's very little info about how these worked online but as far as I can tell, they just used brute force. I mean, I can't think of any other approach, and talking to friends who have done more research into this than me they seem to agree: When you hit the task switch shortcut, the switcher just takes a snapshot of various hardware resources like video memory and CPU register status, saves it all to another spot in memory, then transfers control to another app, all with what we would now call "userland" code - the switcher is just another program running on the computer.

I don't know how popular these programs were, but they certainly had their proponents - since they didn't try to "intercept" the input/output from apps, but mostly let them run as if they were in total control of the system, I imagine they were somewhat more compatible with not-so-well-behaved apps.

But what happens when the program you want to run is even more poorly behaved, if you will? Since these switchers would have needed to "manually" save the state of all hardware resources, they would have to predict what was in use. If a program did anything the switcher wasn't prepared for, like alter graphics card configuration registers, the system could have entered an unusable state or even crashed when a task switch occurred.

Also, while lots of DOS apps were nice enough to pay attention to where they were in memory and only make changes to their own data, nothing stopped any app from scribbling all over system memory and corrupting other programs.

I may not have hard answers to how these switchers worked, but the proof is in the pudding - while you can probably tell me the name of the OS installed on Macs in 1985, and you can definitely name the most popular way to run multiple DOS programs on the PC in 1995, you almost certainly can't name a DOS task switcher or multitasking environment offhand. There were at least a half dozen and none of them are remembered now, which tells us they didn't do brisk business.

You actually can name one of them, though you might not know it. For it's first couple versions, Windows' ability to run multiple DOS apps was a hybrid of "task switching" and the TopView approach. Compatible apps could run in windows concurrently, while apps that wanted to write to the screen and so on were ceded control of the hardware while running. The fact that most people have never seen or heard of these editions of Windows also speaks to how poorly this approach probably went for Microsoft.

To sum it all up, the trick we're discussing here is just incredibly difficult to pull off. Taking programs that were meant to run using the entire resources of a computer and trying to gimmick them into sharing the computer is just incredibly difficult - until hardware changes came that specifically enabled this.

Hardware Advances

The original IBM PC CPU was an Intel 8088, a cost-reduced form of their more-or-less flagship 8086 chip, and throughout the 80s it remained the overwhelming definition of the platform. Though it was an advanced processor perhaps in 1981, in retrospect it looks like little more than a fast calculator now, without a lot of advanced purpose-oriented features. Though Intel released several considerably faster and more advanced processors throughout the 80s, the bulk of PC software targeted the 8086/8088. The newer processors had backwards compatibility modes allowing them to run 8086 software at faster speeds, but only a few programs actually targeted the newer chips.

The 286

The 80286 was Intel's consumer followup to the 8086, and it introduced a much more advanced mode of operation, called protected mode. The full details of this are extremely complicated, but in the simplest terms, protected mode allowed multiple programs to share one PC without being able to interfere with each other. Each process gets locked into an area of memory in which it can do whatever it likes, but an attempt to reach outside of that area results in a CPU-level alert being triggered, at which point the operating system - which actually has a higher privilege level within the CPU itself - is allowed to take over execution and decide what to do about it.

This feature allows you to run multiple programs without worrying that one might overwrite another's memory or crash the entire system. If a program tries to access memory it's not allowed to touch, the CPU stops it, and the OS can step in and make a judgment call - either permitting the access if it thinks it's reasonable, redirecting the access to somewhere else in memory, or stopping the process in its tracks and terminating it.

This is a fantastic capability and could have revolutionized computing overnight when it was released in 1982, except that by that point there was already an enormous DOS software ecosystem. Protected mode completely altered how the system worked, and virtually no DOS software would run correctly in this state. So instead, these chips were largely relegated to running in backwards compatibility mode - called "real mode" - and while they could be switched between protected and real mode, it was extremely slow and awkward, so it had little impact on the PC world.

The 386

The 80386 was the third major leap forward in Intel's x86 processor line, and it would have been very easy at release to totally miss the feature that was going to change how the IBM PC worked completely. I think I actually found some articles in magazines about the 386 which did exactly this - decried it as a simple bump in speed and instruction set that had no real impact on the evolution of the platform.

Buried in the feature list however was something called Virtual 8086 mode, and this feature was in fact a massive step forward for the DOS application ecosystem of the day. It fixed the problems with protected mode, enabling the CPU to run DOS apps and new protected mode apps at the same time, by - in no uncertain terms - running the DOS apps in virtual machines.

This works pretty much like the virtual machines we use nowadays. Each DOS app gets cordoned off into a space in memory where, as far as it knows, it's the only program running on the machine. When it tries to write to, say, the spot in memory where 8088 machines stored their video, the CPU catches those write attempts and alerts the operating system, which can redirect them to a device driver or put them in an entirely different spot in memory so they can be displayed only when the OS chooses.

In fact, all the hardware of the host machine is emulated - the OS presents a "fake" graphics card, a "fake" keyboard, a "fake" hard drive and so on, all of which translate the blunt, simplistic requests of 1981-era software into the polite, cooperative discourse of modern, community-conscious software. In this way, multiple concurrent DOS apps can run in these tiny walled gardens, and as far as they know, each one has a whole PC to itself, while in reality their input and output is entirely simulated - a Truman Show for elderly software.

This is how the Windows that most of us remember worked. By leveraging the capabilities of the 386, Windows was able to run multiple DOS apps simultaneously. Microsoft took a run at making this happen without the capabilities of the 386, but it was not a pretty sight, as you'll see - it was fragile, tedious and limited, and therefore failed to put Windows on the map. Curiously, not even the addition of the 386 to the equation solved this problem - before Windows could gain any respect, it had to make significant leaps forward in the overall user experience.

Now, let's look at how this all worked.