spoilers for Eddington at the very end. don’t say I didn’t warn you!

In middle school I was friends with two sisters with rhyming names who had been adopted by a fairly conservative Christian family. They lived on the next street over; we’d sit near each other on the school bus, ride bikes around the neighborhood, and a few times a week, they’d come over to my house to go on Myspace and play the Sims. We’d sit on my bed and take turns logging into and out of our profiles to update our top 8s and message boys we were too scared to talk to in real life. This all ended one night after their mom came to my parents’ house and furiously waved several sheets of paper containing my printed-out messages in my father’s face. I don’t remember whether they contained profanity or some admission of teenage delinquency but I do remember the smugness with which she told my dad that I was engaging in bad behavior and discussing it on Myspace dot com, presumably without parental consent, to which he responded that her kids were, too.1 I did not get in trouble for this, though there were plenty of other times that my parents punished me for transgressions real or imagined, often by taking away my phone or laptop.2

My phone was constantly being taken away, if not by my parents then by other authority figures. We weren’t allowed to use our phones in school at all: not to call our parents, not to text our friends, not even to listen to music after turning in an assignment. In 10th grade my biology teacher caught me stuffing my phone—I think I had a Blackberry Flip at the time—into my boot so I could go to the bathroom to call someone.3 He confiscated it and didn’t return it until the end of the day. It’s funny to reminisce about this now. Describing my own life like this makes me feel crotchety, like I’m someone’s grandmother talking about walking two miles uphill in the snow to post a thirst trap. But it really was a different world, or at least it felt like it.

I came of age smartphones and social media were starting to become ubiquitous but before they actually were, which may explain why I find the supposed “discourse” around parents being opposed to phone bans in schools so tiresome. On one side are parents who say they want to hear from their kids in the event of a school shooting and also want to be able to text them things like “porkchops for dinner 2nite.” On the other side are teachers who say phones are turning kids into stupid disrespectful zombies. Both have decent points, which has made everyone act like this is some kind of thorny issue, even though the answer is simple: tell kids they can’t use their phone during class. If a kid uses their phone during class then take it away until class is over. If you have taken away a kid’s phone and suddenly there’s an active shooter situation on campus then give them their phone back so they can call their parents. It’s not complicated, at least not if your primary concern is balancing parents’ need to communicate with their children in case of emergency with teachers’—and I’d argue students’—need for a productive learning environment. But parents don’t solely want to communicate with their children in case of emergency; they want to communicate with their children literally all the time, and therein lies the problem.

It’s not just parents. Everyone wants everyone else to be reachable all the time. It’s less a desire than an expectation, though that feels like the wrong word too; it’s just how things are. The ability to communicate with anyone at any time with minimal effort is relatively new, but it’s become impossible for people to imagine their lives without it. The same could be said about other recent developments in human history: DoorDash, Ring cameras, two-day Prime shipping. We didn’t always live this way. We didn’t even live this way a decade ago. The fact that most people can no longer conceive of a world without instant communication and on-demand delivery is not an accident. Tech companies intend for their products to be frictionless; eliminating the barriers that stop a person from spending money is the entire point. “If you’re making the customer do any extra amount of work, no matter what industry you call home,” the CEO of a cloud storage company said in 2012, “you’re now a target for disruption.”

Our phones and all the things we do on them are frictionless by design. To quote Magdalene J. Taylor, the phone you may be holding right now is “both an all-encompassing object and not even an object at all. It is a universe of networks and apps and interfaces backed by the world’s most powerful and wealthy corporations who employ our brightest minds to make their products 1 percent more addictive.” Though it was a device I used to make calls and send messages, the Blackberry Flip my biology teacher confiscated in 2010 hardly counts as a phone under this definition.4

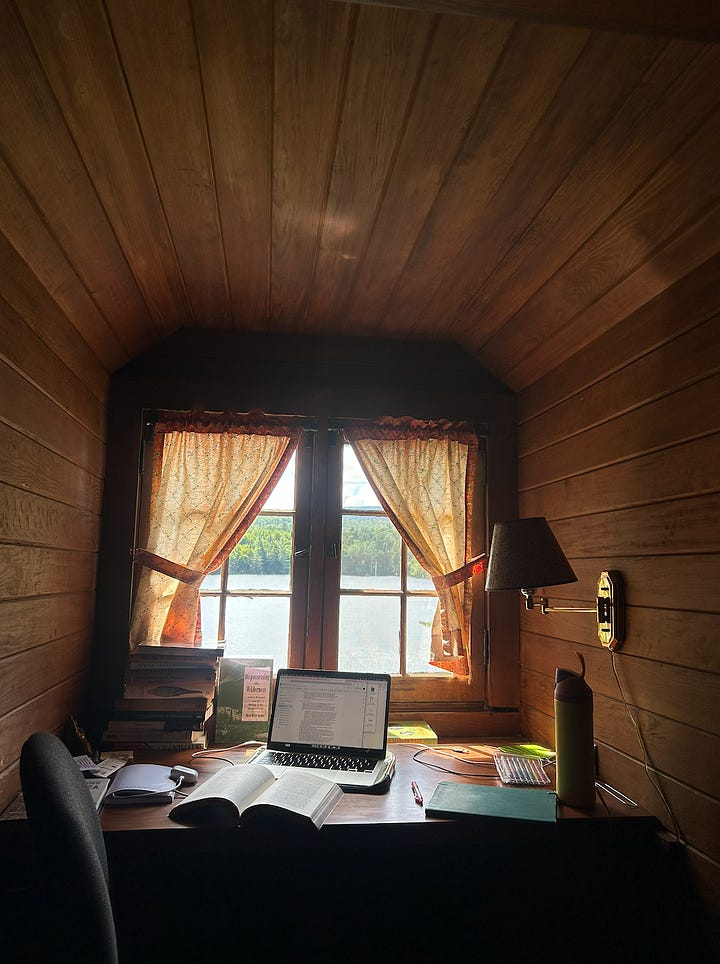

This summer, for the first time in my adult life, I was more or less unreachable. I spent two months in the Adirondacks5 at residencies where I had no cell service and next to no internet access. Whenever I wanted to go online, I had to walk to a specific room: at my first residency it was a barn that had wifi; at the second it was a library with a few ethernet cables. If I wanted to call my parents I did it in the phone booth, from a landline. If I wanted to google anything or check my email or text my friends, I had to stop what I was doing and go to the internet room. If all the ethernet cables were in use I had to wait. Sometimes this friction was frustrating and sometimes it was liberating but it always reminded me of the not-so-distant past; it reminded me that before it was in my pocket or on my wrist the internet was a place.

The pre-phone internet was both spatially bound and, once you were online, limitless in a way I no longer think exists. I’ve written elsewhere about my nostalgia for forums, which is really nostalgia for the internet as it once was. I find Reddit to be a poor substitute; it’s too interconnected, its subforums too accessible to outsiders. This is true of all major social media platforms: things bleed from Twitter to Reddit to Instagram to TikTok to YouTube to OnlyFans to Discord to Substack and then into the real world, if such a distinction even exists. You can rearrange those in any way you want. It’s all more or less the same anyway.

My nostalgia for the pre-FacebookInstagramYouTubeTikTokReddit internet is not unlike nostalgia for mid-aughts fast food chan logos. It’s true that both the internet and the real world were more colorful, textured places when I was a teenager, and yet the thing I find myself longing for is itself a poor substitute for what came before. Myspace was not a community, nor is Cracker Barrel a real old country store. They are, as John Ganz recently wrote, simulacra. I wasn’t around for actual general stores, because I grew up in suburban Florida in the aughts, but I do remember the old internet, and I remember life before the new internet, too.

I moved to New York in 2012; in hindsight it feels like I arrived just in time to catch the end of something. You had to call restaurants to order takeout and you had to hail a cab on the street—I remember fighting for my life on Halloween 2014, competing with every other barely clothed girl on Avenue A for a taxi—and you had to hit on strangers in bars. I didn’t know things were changing until they already had. This is when the creep began, at least for me. My friends and I used fake emails to game the Seamless referral system. My sophomore year roommate and I downloaded Tinder and marveled at the sheer amount of people at our fingertips. I made fun of my friends for using Uber when the streets were full of yellow cabs and for using real money to buy fake internet money6 that they would then use to buy drugs from strangers on the internet. Didn’t they know they could buy drugs outside, with cash, in the real world? It’s not that I wasn’t online. I spent a significant amount of these years years on Tumblr, bedrotting before anyone called it that, reblogging pictures of girls with wider thigh gaps and nicer bedrooms than my own. When I put it that way it doesn’t seem so different from what teenage girls are doing now, except at the time I knew my behavior was that of a hopelessly maladjusted person, and now it’s just what everyone does all the time.

I stopped scrolling when I was in the Adirondacks, mostly because I could no longer do so. At first I would reflexively reach for my phone in the mornings as I always do, and even after realizing there was nothing to see on there—I didn’t have any notifications—it took me several weeks to drop the habit. Those two months in the wilderness rewired my brain. I slept better. I read more. When I did go online, it was to text my friends or read the newspaper. Most of the time I was reading newspapers from 1883 and texting my friends screenshots of the headlines. When I wanted real news I’d flip through the physical paper, which was delivered to us on Sundays, and read past the passive voice (“Dozens die in Gaza…”). For a time I wondered whether it would be possible to keep up with the news if I wasn’t online all the time and then realized most people do the latter and not the former.

The long-term effects of my sabbatical from online were negligible. It pains me to say this. I thought I cured myself but it was only temporary. On the way home I spent hours on r/MyBoyFriendIsAI, which was harrowing for obvious reasons. The people on this subreddit are lonely and desperate for connection; the scrutiny they’ve received from outsiders has made them feel even more isolated, thus reinforcing their perceived need for their AI companions. Meanwhile, the companies behind these companions are constantly updating their models, meaning the companions change “personalities” with every new update. It was difficult to read but I couldn’t stop. I felt a strange mix of revulsion and pity and then I realized what I was actually feeling was recognition.

In the same way they say anyone can join a cult if they’re targeted by the wrong person at the right moment—if they’re vulnerable and alienated and lonely enough, that is—I think maybe anyone can become dependent on an AI chatbot if the right conditions are there. And for most people, the conditions are in fact there! Much has been made about the male loneliness crisis, the fact that Americans aren’t partying anymore, the supposed end of “third spaces,” etc. People are alone, and they are online, and they are lonely. And the chatbots are there for them always, supportive always, understanding always. They are perfect companions in the way human beings are not, because they lack the qualities that make humans messy and fallible. They lack what it means to be human.

I don’t use generative AI7 and find it difficult to respect writers, etc. who rely on it for things like research or idea generation. It’s much easier to understand why a lonely person would talk to a large language model as if it were their friend or romantic partner. Still, it’s hard for me to make sense of how many people engage with LLMs this way, and it seems that even people who use LLMs as a sort of search engine can end up thinking of the chatbot as their friend. ChatGPT in particular seems designed to endear itself to the user. In April, CEO Sam Altman admitted that a recent update had made GPT-4o “too sycophant-y8 and annoying,” which is true enough, though it would’ve been more accurate to say that it was fueling the delusions of clearly mentally ill users. All it took was three weeks of daily conversations with ChatGPT to convince a man described by the New York Times as “otherwise perfectly sane” that he was a superhero. A separate story in the Times recounts the death of a teenager who hanged himself in his bedroom after months of discussing his suicide plans with ChatGPT. At one point the AI told him how to hide ligature marks on his neck from a failed attempt.

AI is the antithesis of friction. ChatGPT similar products are—or at least purport themselves to be—whatever the user needs in that moment. A search engine, a shoulder to cry on, a recipe generator, a packing list, an assistant, a romantic partner, a teacher, a tutor, an editor, a way of getting your work done with minimal effort. All these things and more can be generated in mere minutes, and the highly paid engineers at OpenAI and its many competitors are working on making their products faster and more “intelligent,” which is to say human-like, every day. It’s worth asking ourselves what we have sacrificed on the altar of frictionlessness and whether these sacrifices have been worth it. What does it mean that the tools people rely on to make them feel less alone are instead exacerbating their isolation? It’s a question worth asking of the broader internet, too. It’s a common refrain that we are more connected than ever and also lonelier. It’s the kind of thing a dumb person says to sound smart. But that doesn’t make it any less true.

On my last day in New York9 I saw Eddington with my friend Tisya Mavuram. I’m still working out my thoughts on it, but I was struck by how profoundly alienated nearly all the characters are. The film opens with a homeless man wandering through the streets of the deserted town of Eddington. It’s May 2020; it was, after all, a lonely time. In another early scene, Sheriff Joe Cross sits in his cruiser watching a TikTok about how to convince your partner to have a child with you. His wife, Louise, played by a criminally underused Emma Stone, refuses to be touched. Louise is hardly present in the real world; both she and her mother have fallen down the rabbitholes of right-wing conspiracy, though their fixations differ slightly. The mother sees right through the plandemic; the daughter becomes obsessed with child sex trafficking, a monomania that is clearly the product of her own childhood abuse.10

Louise is, in her own way, crying for help. Neither her husband nor her mother read anything into the terrifying dolls she makes. To Joe, they’re her weird little hobby, a project that makes her busy and boosts her self esteem; he has his deputies buy them on Etsy. When Vernon Jefferson Peak, a charismatic cult leader played by Austin Butler comments on the dolls, Louise’s mother says she’s been making them since she was 10. Vernon—who has an outlandish story about having been set loose in the Bohemian Grove to be hunted down and raped by his father and other powerful men, Most Dangerous Game-style—is the only one who makes the connection between Louise’s art and her trauma.

It doesn’t come as a surprise when Louise runs off with Vernon, leaving her mother and husband to their own devices. Her absence doesn’t change much. Each member of the Cross household remains in their own world and on their phones. In Eddington, as in our lives, the lines between the internet and real life are so blurred as to be nonexistent. The plot focuses on Joe’s insurgent mayoral campaign against Ted Garcia, a smug liberal who appears to be a puppet of SolidGoldMagikarp, a nefarious tech company that wants to build a data center in Eddington. (SolidGoldMagikarp, by the way, is a phrase that used to basically break ChatGPT.) While the election is a war between the town’s pro- and anti-mask factions, these distinctions don’t really matter in the end. Garcia dies, Joe becomes mayor, but not before being paralyzed in an “antifa” attack that was almost certainly orchestrated by SolidGoldMagikarp, and everyone continues to be on their damn phones, alone as ever.