On the day Captain Sumeet Sabharwal earned his wings, his father, Pushkaraj Sabharwal, who was then a senior Aviation Ministry official, happened to see his son’s commercial pilot licence file arrive at the office for clearance. A colleague recalls the moment: his posture was straight, his expression composed, almost offhand. The only giveaway was a flicker of pride in his eyes.

The pride was justified. Sumeet’s batchmates recall him as the class topper with lightning reflexes and perfect scores. Sumeet was the guy who mastered the systems before instructors could finish their briefings and who could be unnervingly calm in both real-world and simulator emergencies. “He absorbed procedures like [they were] oxygen,” his batchmate recalled. “If you flew with Sumeet, you knew you and the aircraft were safe.”

It is this absolute confidence in his son’s character and competence that drove the 88-year-old Pushkaraj, a former official of the Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA), to petition the Supreme Court, urging that an independent body other than the Aircraft Accident Investigation Bureau (AAIB) of India’s Ministry of Civil Aviation examine the chain of electrical failures that occured on the Air India 171 aircraft that crashed in Ahmedabad on June 12, 2025, within minutes of take-off.

Pushkaraj’s petition is a blistering criticism of the AAIB’s preliminary report. He has channelled his grief into a methodical dismantling of the AAIB investigation, which, he believes, has failed his son, his son’s colleagues, the crash victims, and the truth. He has pointed out glaring anomalies in the investigation and stated that the bureau violated international aviation norms when it allowed Boeing and GE—whose plane and equipment, respectively, are implicated in the crash—to have a seat at the very table meant to hold them to account.

The AAIB’s preliminary report says that AI171 lifted off normally, then—within seconds—both engine fuel cut-off switches moved to CUT-OFF mode, the engines spooled down, meaning their rotational speed fell, the ram air turbine (or RAT, designed to deploy only in emergency situations such as dual engine failure) deployed, and the aircraft lost altitude, before crashing into the ground. The report attributes the sequence to an unexplained in-flight shutdown of both engines, notes the pilots’ denial of having commanded cut-off, and says the investigation is ongoing with no conclusions yet on cause.

Pushkaraj’s petition turns the spotlight to where it belongs: on the data, maintenance logs, and the documented malfunctions that occurred in the final seconds of the AI171 flight before it crashed, killing 260 people, in one of India’s deadliest aviation disasters.

Evidence shows that AI171’s 12.5-year-old Boeing 787-8 Dreamliner aircraft with registration VT-ANB faced 3 major electrical failures and the malfunctioning of 11 minor components in the 48 hours preceding the crash. But the media maelstrom around the crash focussed only on the “fuel switch” aspect, which the AAIB report highlighted and, as Pushkaraj noted, “selectively quoted”.

The AAIB report said both engine “fuel-control switches”, which should stay in RUN during take-off, suddenly moved to CUT-OFF one second apart, starving both engines of fuel. This unexplained switch movement became the media’s focus because the flight deck audio captured one pilot asking the other, “why did you cut off?” even though the report itself does not establish that either pilot actually touched the switches.

Also Read | The Air India crash was one tragedy—what’s scarier is the state of Indian aviation

Engineers whom The Federal news website spoke to said that considering the malfunctioning of electrical and other components, AI171’s dual engine failure should not be seen in isolation. There were multiple failures, each signalling stress with the same electrical ancestry, starting with a fault on the core network—the backbone powering the aircraft’s entire data and avionics layer: 1. The Nitrogen Generation System (NGS), or fire inerter in the tail of the aircraft, failed to deploy the day before the crash; 2. a stabiliser-trim motor broke down during the inbound leg of the flight on the day of the crash; and 3. the aircraft’s bus power control unit (BPCU), or dual power controller, showed some instability just 15 minutes before take-off.

Thus, the safety of the aircraft had unravelled, system after system, component by component, all with a common starting point: the core network connecting 22 flight critical systems, including the flight engine computer known as FADEC, and another 28 non-flight-critical systems. When there are issues with the core network, it can affect the functioning of the FADEC and possibly trigger a fuel cut-off mid-air, the engineers said.

The AAIB’s overall narrative of the crash, therefore, needs to be examined, say aviation experts. Its preliminary report has too many contradictions and too many missing pieces of data, such as crucial time stamps on fuel cut-off, engine fan speed, and RAT deployment.

The condensed reconstruction of events that follows integrates new findings from reportage published on The Federal.

The lead up to the crash

The Federal’s investigation focussed on the core network issue that was designated as an active fault—a CAT C MEL, or “medium risk”—as per the AAIB’s report. The Minimum Equipment Lists (MELs) catalogue certain tolerated faults with which a plane is still allowed to fly and are classified into categories as CAT A (for which rectification time is specified by the MEL team), CAT B (issue to be fixed within 3 days), CAT C (10 days), and CAT D (120 days).

Since the issue with the Boeing 787-8 Dreamliner aircraft that would fly as AI171 was categorised as CAT C, the rules allow for such an issue to be fixed within 10 days. Maintenance engineers flagged the issue on June 9, 2025. Air India had 10 days to fix it, given the CAT C, or medium risk, classification. But the plane crashed on the third day.

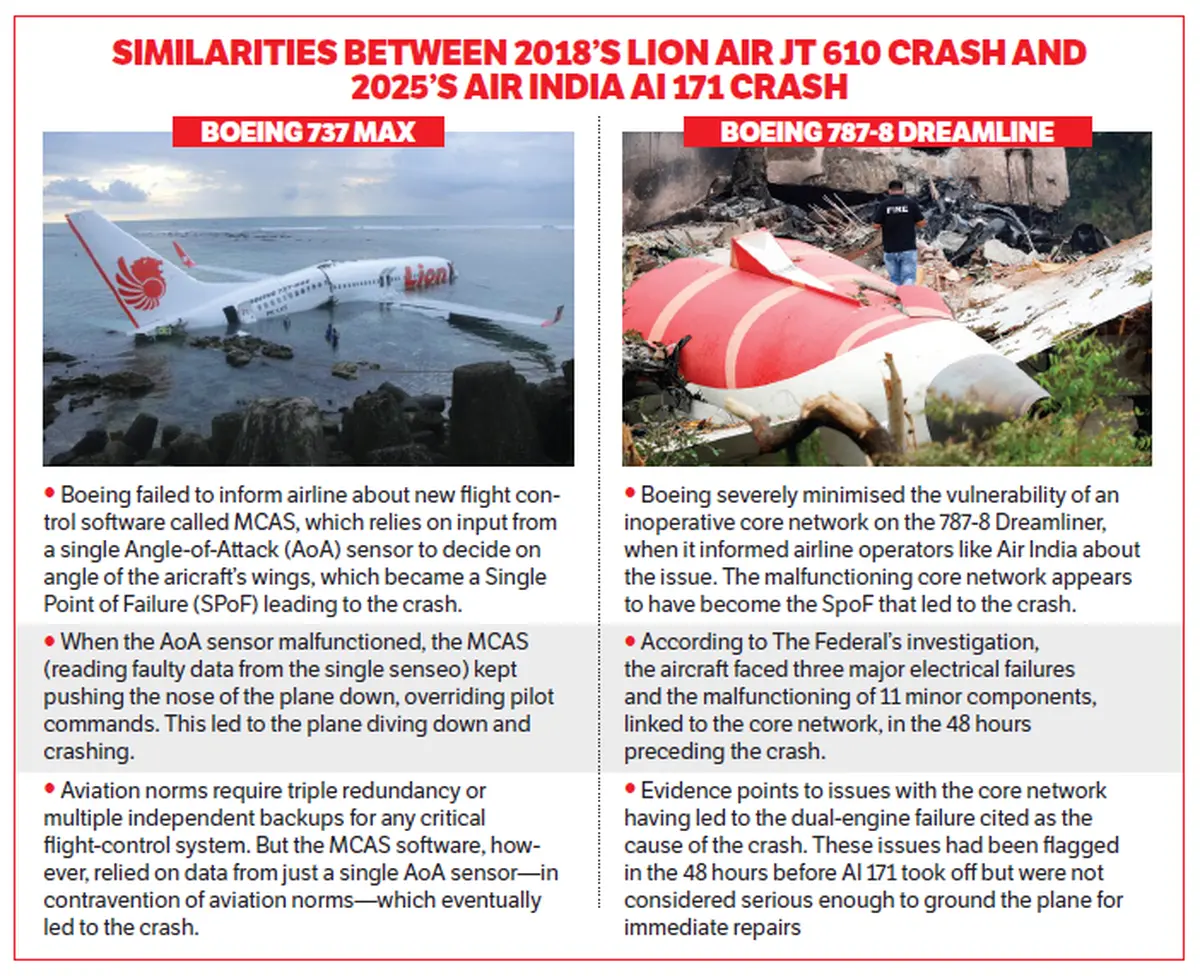

This begs the question, how was an issue with a flight-critical system like the core network designated as “medium risk”? In this regard, the AI171 crash has an eerie resemblance to the Lion Air JT610 crash, a Boeing 737 MAX, on October 29, 2018. In that case, Boeing had not informed maintenance personnel or pilots that it had introduced a flight control software called Manoeuvring Characteristics Augmentation System (MCAS) on the aircraft. This MCAS software on Lion Air JT610 relied on input from a single angle-of-attack (AoA) sensor (which indicates what angle the wings are at in relation to the direction of airflow around them). Aviation norms require triple redundancy or multiple independent backups for any critical flight-control system. This software, however, relied on data from just a single AoA sensor in contravention of aviation norms.

When the AoA sensor malfunctioned, the MCAS kept pushing down the nose of the plane after take-off, repeatedly overriding pilot commands until it sent the Lion Air JT610 plane crashing into the depths of the Java Sea. Even as one person stayed calm at the helm, repeatedly communicating with air traffic control (ATC) and fighting valiantly until the very end, the unknown—the ghost software he had never been told about—brought the plane down. That was Captain Bhavye Suneja, the Indian pilot of Lion Air JT610.

Fast forward to 2025. Another crash, another Indian pilot blamed, and another Boeing aircraft with a hidden single point of failure (SPoF) buried deep inside. An SPOF is the part of a system that stops the entire system from working if it fails.

Single Point of Failure

In the Lion Air JT610 crash, the fatal flaw lay in the MCAS depending on just a single AoA sensor to decide how the aircraft should move. In the AI171 crash, the vulnerability lay in the design of the Boeing 787-8’s core network, which hosts multiple critical computers, including the central core computers. Cybersecurity experts at IOActive, an independent computer security services firm, had already warned in 2020 that this design flaw could act as a catastrophic SPoF.

In the case of Lion Air JT610, Boeing did not inform airline operators, pilots, or maintenance engineers about the MCAS issue on the 737 MAX; in the case of AI171, the aircraft manufacturer severely minimised the vulnerability of an inoperative core network on the 787-8 Dreamliner when it informed airline operators like Air India about the issue.

Boeing’s own operations note to air carriers illustrates how the company framed the issue. It stated that “an inoperative core network… may render the following functions inoperative: the airport map function, flight deck printer, and flight deck door video surveillance”. In other words, Boeing claimed that only minor, non-flight-critical features would be affected, its message to operators being that failure in a core network is merely a trivial inconvenience.

The AAIB report shows that the “flight deck door visual surveillance, airport map function, flight deck printer” were categorised as a MEL issue alongside the core network fault on June 9, 2025. Boeing’s own internal documents describe the 787-8’s core network as the aircraft’s digital spine, linking more than 50 systems, including the data-handoff unit, or Network Interface Module; the data-traffic router, or Ethernet Gateway Module; the avionics command processor, or Controller Server Module; and even the aircraft’s twin mainframes inside the Common Computing Resource cabinets that host the Common Core System. When this backbone is not working as it should, the damage would not be limited to the “minor features”. It can ripple through the flight control modules—the computers that command the aircraft’s control surfaces—and from there corrupt the data feeding the FADECs, the computers that control the engines, according to Boeing’s own literature.

In short, a degrading core network is never “minor”; it is an SPoF risk of exactly the kind that brought down the 737 MAXs. And yet Boeing convinced the US Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) that a core network fault was “medium-risk” (CAT C MEL), a classification the DGCA in India accepted. So, even if the maintenance engineers in India who conducted checks on June 9, 2025, had any reservations, they would have still had to release the aircraft for operations after marking the core network issue as CAT C MEL.

The second major fault surfaced on June 10, 2025. The NGS failure was marked as “high-risk”, or CAT A MEL, by the maintenance engineers. This fire inerter’s job is to prevent fuel-tank fires by injecting nitrogen-rich air into them to prevent a vapour build-up of the flammable gas oxygen. When the NGS is offline, oxygen levels can rise inside the fuel tanks.

As the NGS did not function in flight AI171, it meant that there was nothing to immediately slow down or suppress the fuel fire that erupted when the aircraft hit the ground. If the inerting system had done its job, the initial fire could have been smaller, and there might have been more than one survivor, say aviation experts.

Coming to the electrical issue, two days after the fire inerter issue was logged on June 10, on June 12, the day of the crash, the aircraft’s stabiliser-trim motor and sensors also failed. Both are siblings on the plane’s electrical network, tracing their ancestry back to the same source: the engine-mounted main generator or the variable frequency starter generator, which feeds the 235 volt AC main buses.

The AAIB’s report showed photographs of the tail section of the 787 aircraft remaining structurally intact and noted that the backup generator or auxiliary power unit (APU) was recovered intact. However, a few feet away, the black box, or enhanced airborne flight recorder (EAFR), at the aircraft’s tail was so badly damaged that the AAIB noted that its housing and connectors were burnt. The AAIB report also mentioned that the distress beacon, or emergency locator transmitter (ELT), had “not activated during this event”. Engineers said these are hallmarks of an electric arc where only specific components in the line of the fire get scorched but nothing else is affected.

Pushkaraj Sabharwal at the funeral of Captain Sumeet Sabharwal, his son, in Mumbai on June 17. | Photo Credit: EMMANUAL YOGINI

A father’s fight

Pushkaraj Sabharwal’s petition in the Supreme Court says the AAIB suppressed key evidence and shielded Boeing and GE

When India’s Aircraft Accident Investigation Bureau (AAIB) released its unsigned and undated preliminary report on the Air India 171 crash, it carried one chilling line from the flight deck: One pilot is heard asking the other why he cut off. The other pilot responds that he did not do so.

That started off the media trial and witch hunt against Captain Sumeet Sabharwal for the crash in which 260 people died, including him. His father, Pushkaraj Sabharwal, 88, a former DGCA official, termed it “narrative framing to blame the dead pilots” and said the AAIB should have released the entire flight deck recording or “none at all”. By releasing just two lines from a recovered audio that is two hours in length, “is AAIB weaponising selective disclosure?” he asked.

In a writ petition before the Supreme Court, the grieving father said the AAIB’s actions are in violation of international law as it suppresses key evidence and shields Boeing and General Electric from scrutiny. What is worse, he said, was the AAIB’s “attempt to provide a clean chit to the aircraft and the engine manufacturers”. He quoted AAIB’s remark: “At this stage of investigation, there are no recommended actions to B787-8 and/or GE GEnx 1B engine operators and manufacturers.”

The AAIB is “insinuating pilot error at a stage where only bare facts were meant to be revealed”, he said, wondering how media outlets like The Wall Street Journal had sourced flight deck recordings “that even today the Indian public doesn’t have”.

Pushkaraj said that “by law, under Rule 17(1) of the Aircraft (Investigation of Accidents and Incidents) Rules 2017, cockpit [flight deck] recordings may not be disclosed for any purpose other than investigation—unless the government expressly determines that the benefits of disclosure outweigh the harm”.

The petition also names a more serious problem—the presence of Boeing and General Electric personnel inside the investigation. It is “a textbook case of conflict of interests”, as the companies that are implicated are at the table with the AAIB helping shape the evidence.

He also criticised the AAIB for not confining itself to “what happened” but straying into “why it happened”, violating International Civil Aviation Organization Annex 13, which limits preliminary reports to factual data.

His plea highlights how the AAIB’s narrative maligns and tarnishes “the reputation of a highly qualified professional pilot in a situation where he is not even alive to plead his own case”.

The next hearing on this and two other petitions are scheduled for January 28. The Supreme Court has directed the Union Ministry of Civil Aviation to respond to the issues raised in the petitions.

Hours before the crash, the 787-8 aircraft suffered a hard, abnormal descent on its inbound flight (AI423) due to an issue with one of its flight control systems: the stabiliser-trim motor. The AAIB report mentioned that the pilots logged a stabiliser-position sensor fault, but it failed to mention what the maintenance staff logged.

According to the maintenance log, the right-side stabiliser-trim electric motor control unit had failed, and it had been replaced along with the wiring and stabiliser sensors. This was mentioned in the aircraft health monitoring report sent to Boeing and Air India at 6:40 UTC (12:10 pm IST) on the day of the crash.

Both crashes appear to have a single point of failure. | Photo Credit: Graphic: B. Srinivasan

The AAIB report said: “The crew of the previous flight (AI423) had made Pilot Defect Report entry for status message “STAB POS XDCR” in the Tech Log [technical log that details the status of the aircraft]. The troubleshooting was carried out as per FIM [Fault Isolation Manual] by Air India’s on duty AME [aircraft maintenance engineer], and the aircraft was released for flight at 06:40 UTC [12.10 pm IST].”

The status STAB POS XDCR translates as a malfunction in the stabiliser position transducer, the sensor that sends inputs to flight computers and pilots to help them control the plane’s surfaces. The issue had been fixed by the AME as per Boeing’s FIM—meaning the engineers did what Boeing told them was the correct thing to do.

Critical electrical failures

In hindsight, Air India engineers said, the airline and Boeing should have given engineers more leeway, authority, and time to examine the failures—because they all seem to point to a bad power domain, which the replacement of the stabiliser trim motor and sensor does not seem to have fixed. The AAIB report said that AI423 touched down at 5:47 UTC (11:17 IST). That means the maintenance engineer had less than 45 minutes to identify and fix a problem with one of the plane’s main flight control surfaces.

A petition in the Supreme Court noted that 15 minutes before AI171 took off, or 1:23 pm IST, the aircraft logged faults in the dual power controllers and the flight deck tablets, or the captain’s Electronic Flight Bags. This is a PIL petition filed by Captain Amit Singh, who heads the Safety Matters Foundation, an aviation safety organisation. The PIL petition has been clubbed with the cases filed by the pilots’ unions and Captain Sumeet’s father. It talked about how the fault in the electrical traffic controllers signalled a pre-take-off critical electrical failure—as it can cause surges, flickers, or even short circuits across systems.

Information about these faults was being streamed in real time to Boeing and Air India. Second by second, Air India’s subcontractor SITA (the information technology provider for the air transport industry) and satellite network provider Inmarsat were hosting the feed of the Aircraft Communications Addressing and Reporting System (ACARS). “Boeing’s data monitoring hub in the US probably knew within seconds after the crash the exact sequence of events,” said Ed Pierson, executive director for the Foundation of Aviation Safety and a US military veteran and former Boeing senior manager.

“Intermittent system failures could be indicators that there was something wrong with the electrical system on the plane,” said Pierson, adding that “even in the 737 MAX disasters, there were electrical system failures occurring nearly a month before the crashes”.

Boeing, Air India received live fault reports

Boeing would have known, so too would Air India—thanks to the live ACARS feed that was constantly updating Boeing and Air India, sending them warnings through the day of the crash, June 12, 2025, including at 1:25 pm IST, when the plane received taxi clearance from the ATC two minutes after both its power controllers had malfunctioned.

The AAIB says the RAT began supplying hydraulic pressure at 1:38:47 pm IST. Aviation Herald editor Simon Hradecky, in his sworn testimony to the AAIB, has stated that the RAT takes about six seconds to spin up. This means the RAT likely deployed at around 1:38:41-42 pm IST. Then the electrical disturbance that might have triggered it likely took place at 1:38:40 pm IST—one second after take-off at 1:38:38 pm IST.

This is the information that raises serious questions about the AAIB’s narrative, engineers said. The RAT deploys only under three conditions: loss of engine-driven electrical power, loss of instrument-bus power, or loss of all three hydraulic systems.

The lone survivor of the AI171 crash, Vishwas Ramesh Kumar, performs the last rites for his brother Ajay Ramesh, who was travelling on the same flight, in Diu on June 18. | Photo Credit: ANI

Hradecky says one of the conditions for the RAT to deploy is if the BPCU detects loss of power on the C1/C2 TRU lines (the C1/C2 TRU lines are the 787’s two main “converter channels” that turn high-voltage AC from the generators into the stable 28 volt DC needed for flight-critical systems; if both lines lose power, the BPCU triggers RAT deployment as a last-resort energy source), which steps down the main engine generator supplying power to the flight instrument buses from 235 volt AC to 28 volt DC. These same C1/C2 TRU lines also feed the core avionics racks and the flight deck tablets. So, when the aircraft’s dual power controllers and the tablets malfunctioned at 1:23 pm IST, two minutes before taxi clearance, it meant that the very same power path needed to keep the instrument buses alive was already unstable before the aircraft even pushed back from the gate, the engineers say.

The RAT deployment on AI171 could thus indicate systems failure, as it deployed even before the aircraft “cleared the airport perimeter wall”, as the AAIB report notes.

Boeing 787-8 Dreamliners grounded after crash

After the AI171 crash, Air India grounded three Boeing 787-8 Dreamliners—two overseas and one in India—for extended inspection.

The first aircraft, VT-ANA, was grounded in Amman, Jordan, from August 5 to October 11 at Joramco, one of West Asia’s largest independent wide-body heavy-maintenance facilities. According to experts, Air India sends planes to the Jordan facility only for long-duration structural inspections, heavy checks, and modification work.

A second Dreamliner, VT-ANE, was grounded from July 15 to September 24 at Etihad Engineering’s wide-body Maintenance, Repair, and Operations (MRO) complex, which specialises in composite structural repair and heavy checks. A third, VT-ANG, has been parked in India at the Mumbai MRO since July 25 for extended troubleshooting.

The three long-haul jets were sent to these heavy-maintenance hubs before Air India CEO Campbell Wilson made statements about the AI171 crash at the Aviation India event held in Delhi on October 29, 2025. Citing the AAIB’s interim report, he had then said: “There was nothing wrong with aircraft’s operations or practices that required changing.”

Also Read | How safe are our airports?

Since the AI171 crash, Air India’s 787-8 fleet alone has suffered three serious events: within a week of the crash, AI310 (Hong Kong-Delhi) turned back soon after take-off; AI117 (Amritsar-Birmingham) saw an uncommanded RAT drop on October 4; and AI154 (Vienna-Delhi) was diverted to Dubai on October 9 after a failure in autopilot mode. Globally, LATAM LA603 (Los Angeles-Santiago) had a RAT deployment on July 31, and United UA108 (Dulles-Munich) reported an in-flight engine shutdown on July 25. Together, these point to a pattern of problems beyond a single aircraft.

Boeing itself, in a recent statement, said there had been 31 incidents of uncommanded RAT deployment in Dreamliners since their launch. But it did not clarify whether the AI171 crash was included in the count.

The failures that led to the AI171 crash are all mentioned in the AAIB report, ACARS records, and maintenance logs. The core network degraded; the aft power domain weakened; the stabiliser-trim motor failed; the dual power controllers malfunctioned destabilising power routing; the RAT deployed; and the ELT wiring burned.

Unrecovered aft-black box had crucial missing data

Also, the aft black box died mid-flight. The aft EAFR, which is dependent on the main electrical power from the engines, did not have an independent battery backup like the forward EAFR. With AAIB unable to recover the aft EAFR data, the crucial missing information is not what it recorded but what time it stopped recording. Because the second it stopped recording is likely the point when the systems failure began.

When an electric surge ripped through the plane’s core network and hit the forward and aft avionics bay, it would have impacted flight control computers and ultimately the functioning of the FADEC. The Federal has evidence, from two sources independent of each other, that at 13:38 IST, an ACARS fault code (247450002 597, 252390002 597) showed how both the forward and aft avionics power buses were down, possibly impacting the flight control computers and the engine computer FADEC.

AI171’s system flashed an “EM12R0” warning, a likely indicator that airspeed data had failed as the FADEC was getting invalid or contradictory data. In EM12RO, the EM refers to “Engine Monitoring” and the 12RO to the channel 12 internal total air temperature probe dropping to zero (R0). This condition, where the FADEC is not getting trustworthy data, can result in it triggering protection logic or in other words initiating a fuel cut-off mid-air.

The parallels between the 787-8 Dreamliner and the 737 MAX crashes cannot be ignored. The AoA sensor that malfunctioned, resulting in an MCAS logic error was a single point of failure hidden inside the 737 MAX’s certified redundancy. The core network issue of the 787-8 seems similar: a central spine that Boeing insists is isolated, but that real-world failures show may not be.

IOActive warned in 2019 that partitioning (software partitioning inside the 787’s Common Core System, which is hosted on the core network, the virtual “walls” separating different avionics domains) does not guarantee real isolation when the underlying hardware power buses and data paths share common points of failure. Engineers who The Federal spoke to insisted that core network corruption can cross domains. The FAA had flagged power vulnerabilities in the 787-8’s architecture and recommended power “recycle” (when an aircraft system or power channel is fully turned off and then back on again so that it reboots—basically an avionics reset to clear latent faults or corrupted states).

The distinct possibility emerges that AI171 crashed soon after take-off because of a weakening electrical chain that regulators, engineers, and the manufacturer had multiple chances to spot and fix.

The man shouldering the blame, however, is the late Captain Sumeet. As his father petitions the Supreme Court, he is fighting not just for justice for his son but also for Sumeet’s colleague, First Officer Clive Kunder, and the other victims of the AI171 crash.

This report is based on a four-part investigative series originally published by The Federal.