Hi,

Morgan here, researcher at Examine.

I love coffee. And I’m not alone: According to some estimates, about 1 billion people drink coffee every day. Good thing, then, that moderate coffee consumption seems to be generally healthy. As Hippocrates said, “Let coffee by thy medicine.” (Okay, he didn’t actually say that.)

But when is the healthiest time to drink coffee? The better question is: When is the healthiest time to not drink coffee?

Coffee can disrupt sleep

A lot of us are drinking coffee because it wakes us up in the morning. You don’t need me to tell you that, but it’s helpful to begin our discussion from a common foundation: many studies show that caffeine from coffee negatively affects sleep quality and sleep duration when ingested later in the day.

This sleep-disrupting effect of caffeine has the potential to undermine some of coffee’s health benefits. Getting enough sleep is essential for good health, after all.

How late is too late to drink coffee?

To answer that question, let’s get statistical.

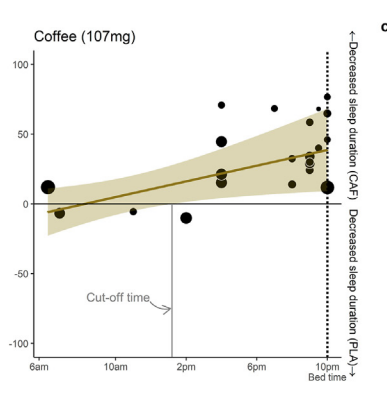

After analyzing data from 24 studies, one group of researchers estimated that it may be best to drink your last cup of coffee no later than 9 hours before bedtime if you want to maximize your sleep quality. If you go to bed at 10 p.m., that would mean you should curtail coffee (drop the drip, say no to a cup of Joe) around 1 p.m.

But let me emphasize: this number was based on statistical modeling, not direct experimental testing. So this conclusion is not exactly watertight (coffeetight?).

More importantly, people vary substantially in their caffeine tolerance, which makes it nearly impossible to recommend a universal coffee cut-off time for everyone.

In fact, some research has found that moderate amounts of caffeine — about 100 mg — has little obvious effect on sleep in some people, even if ingested a few hours before bed. This was actually a conclusion of one of the very first double-blind, placebo-controlled trials ever conducted, a 1915 study which found that caffeine worsened participants’ sleep quality, but “a few individuals showed complete resistance to its effects”.

Why does caffeine sensitivity vary so much from person to person?

I’m glad you asked!

One factor is genetics, particularly variations in the ADOA2A gene, which affects the adenosine receptor, the main target of caffeine’s effects in the brain. Specific variants of the ADOA2A gene make people more sensitive to the sleep-disrupting effects of coffee. I suspect I have this gene variant, because a cup of coffee at 3 p.m. turns me into a night owl, whereas normally I’m what you might call an afternoon pigeon.

Genetics also affects caffeine metabolism, influencing how long caffeine stays in your system and thus, its effects. Depending on the person, the half-life of caffeine can be anywhere from 1.5 to 9.5 hours! In other words, some people’s bodies spit out caffeine like watermelon seeds at a picnic, while in others caffeine hangs around like that ugly family heirloom you just can’t bring yourself to get rid of. Unsurprisingly, one small study found caffeine was metabolized slower in people who reported sleep disturbances when drinking coffee compared to people who didn’t.

Dietary factors also play a role in caffeine metabolism. For example, cruciferous vegetables stimulate CYP1A2, the enzyme that metabolizes caffeine, so eating a lot of broccoli and cabbage might make evening coffee more tolerable (though you might be less pleasant to share an elevator with). Apiaceous vegetables like carrots, parsley, and celery seem to do the opposite, inhibiting CYP1A2 and slowing down caffeine metabolism.

Specific medications can also slow caffeine metabolism, including certain antidepressants (fluvoxamine), antibiotics (norfloxacin), and oral contraceptives.

Having said all of this, it can be hard to tell whether drinking coffee late worsens your sleep if the effect is subtle. Research shows that people can’t always tell when they slept worse. Plus, some people might be so used to sleeping poorly that they don’t even notice when coffee makes it a bit worse.

All I’m saying is, if sleep is a priority, don’t assume you’re immune to coffee’s negative effects on sleep quality.

There you have it. Caffeine tolerance varies a lot, so any recommendation about when to drink coffee is going to be flawed when applied to an individual. I think a good general approach is to limit coffee in the afternoon and evening, especially if you’re prone to sleep issues. But again, health is rarely one-size-fits-all.

If you enjoyed this email and are still jonesing for more information on caffeine, including its interactions with drugs and supplements — and how these interactions might affect sleep — I recommend checking out the Examine caffeine safety database.

Warm regards (and warm coffee),

Morgan Pfiffner

Editor of Examine’s Research Feed